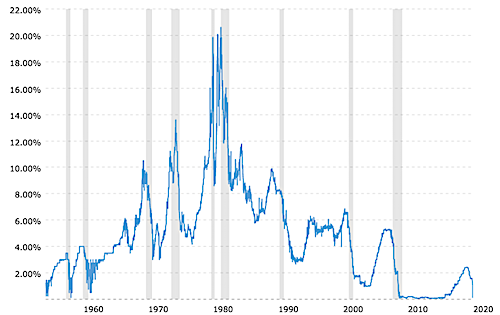

In 2018, a light flashed at the end of a long tunnel of low interest rates. By December of that year, the Fed funds rate had ticked incrementally up, to 2.4% from 1.4%. The yield on 10-year Treasury bonds reached 3.23%. The yield on AAA corporate bonds pierced the 4% barrier.

I started feeling optimistic about Boomer retirement.

If the Fed stayed the course set by chair Janet Yellen (who raised rates from 0.07% in February 2014 to 1.42% in February 2018) and maintained by her successor, Jerome Powell, bonds and annuities had increasingly attractive yields. U.S. retirees might have low-risk, inflation-beating alternatives to stocks after a long drought.

But that light at the end of the tunnel was an oncoming train—perhaps the “R” train to Whitehall Street in Manhattan’s financial district.

In 4Q2018, as the Fed funds rate tightened to 2.2%, there was an equities sell-off. The S&P500 fell 17.5% (to 2,416 from 2,929). Perceiving the swoon as a political liability, President Trump floated a trial balloon about firing Powell.

Despite the Fed’s supposed “independence,” Powell flinched. He reversed the tightening policy and lowered the Fed funds rate three times in 2019. The S&P500 would roar to 3,380 by the following February—a gain of 40% in less than 14 months. Then along came a pandemic, and the index fell 35%, inspiring a rate cut to zero.

The ‘Fed Put’

You’ve heard of the “Fed put.” It’s shorthand for Alan Greenspan’s accommodative Fed policy—a sharp drop in the Fed funds rate—in response to financial market crises starting in the late 1980s. Traders came to expect Fed to ease rates to relieve a slump in stock and bond prices. The expression isn’t necessarily complimentary. It implies an unhealthy codependency, conducive to moral hazard, between the Fed and the equity markets.

The Fed’s accommodation of the Street has been terrible for annuity issuers, pension funds and aging Boomers who need safe, viable alternatives to the stock market to fund their retirements. Three times over the past two decades, falling rates have come to the aid of the markets, and subsequently rising rates have triggered crashes. This volatility is great for traders. It’s a nightmare for the rest of us.

COVID-19 will inevitably take the blame for the 2020 stock crash (and the recession or even depression that may follow). Of course that’s a big factor. But Fed accommodation helped pump the S&P500 Index up by an unwarranted 33% after December 2018. It was ripe for profit-taking when the coronavirus pandemic struck the U.S., and fell 35% in two weeks.

Now we’re back to zero rates. If we follow the roller-coaster pattern set over the last 20 years, we’ll see another rise in stocks, then a reach for yield and over-leveraging, then a cautious tightening until, Boom, the Jenga pile collapses again and we’re back to low rates. It’s getting old, and so are the Boomers.

Letter to Financial Times

Desmond Lachman, a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), former Salomon Smith Barney economist, International Monetary Fund official, and lecturer at Georgetown and Johns Hopkins, is also fed-up with this whipsaw. In response to a March 18 op-ed piece in the Financial Times by Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen, Lachman wrote:

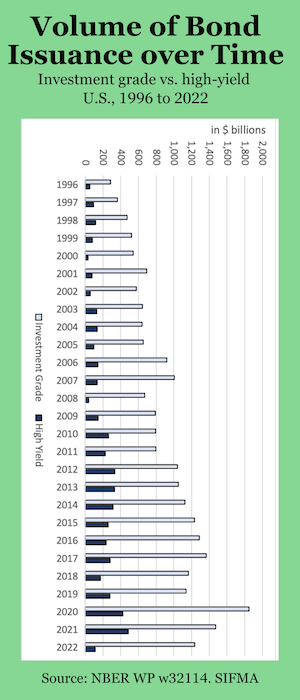

The Federal Reserve’s monetary policy under their watch might have set us up for the financial market turmoil that we are experiencing today. Along with the world’s other major central banks, it did so by creating a global equity bubble and by causing the gross mispricing of credit risk as investors were encouraged to stretch for yield.

On the basis of their experience, it would have been both helpful and timely had the former Fed chairs cautioned that we should not repeat the mistake of responding to the current economic and financial market crisis as we did to the last one by putting an undue burden on monetary policy for promoting the next economic recovery.

Lachman was scheduled to participate in an AEI-sponsored panel discussion last Wednesday entitled, “Is this global credit and asset price bubble really different?” The panel’s premise was that “Many years of ultra-easy monetary policy by the world’s major central banks have boosted global debt to record levels, supported a worldwide equity market boom, and reduced interest rates to unprecedentedly low levels. This event will consider how the current credit and asset market bubble might end and how policymakers should be preparing themselves for that ending.”

Ironically, this timely panel was cancelled due to the coronavirus.

“They got the economy moving after 2008 by creating an asset bubble,” Lachman said in a phone interview with RIJ last Monday. “They encouraged people to take on a huge amount of risk and lend to borrowers in ways that didn’t compensate for the risk of default. We should have had helicopter money in 2008-2009 instead of the Fed distorting financial markets.”

By reducing rates to almost zero, and forcing investors to reach for yield by taking on more risk, the central banks have only set the US and European economies up for a bigger bust in the future. “I think were in the ‘bigger bust’ now,” Lachman said. “And we’re going to repeat the same scenario. They’ll do all sort of things to prop up assets, and that will set us up for another fall.”

Analysis of FOMC records

This month, Anna Cieslak of The Fuqua School of Business at Duke and Annette Vissing-Jorgensen of California-Berkeley’s Haas School of Business published a paper on Fed policy up to 2016 in the article, “The Economics of the Fed Put” (NBER Working Paper 26894).

The investing public is aware of the presence of a Fed put, they found, basing their conclusion on reviews of news reports and minutes or transcripts of the FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee). “We show that since the mid-1990s the Fed has engaged in a sequence of policy easing following large stock market declines in the intermeeting period. We refer to this pattern as a ‘Fed put,’ by which we mean policy accommodation following poor stock returns,” they write.

But the Fed, they believe, behaves responsibly. It lowers rates out of concern that a falling equity market will lead to a smaller “wealth effect,” reduced personal consumption, a slower economy, and weaker corporate earnings, they conclude.

“We find that negative stock returns predict target changes [Fed funds rate reductions] mostly due to their strong correlation with downgrades to the Fed growth expectations and the Fed’s assessment of current economic growth,” Cieslak and Vissing-Jorgensen write.

From internal Fed communications through 2016, they don’t find evidence that the Fed has over-reacted to stock market changes, or that the majority of governors believe that they’re encouraging moral hazard (i.e., stimulating excessive risk-taking) by traders by lowering rates.

“While the FOMC [Federal Open Market Committee, which alters the Fed funds rate by buying or selling Treasury bonds] is clearly aware of the potential moral hazard effects of loose policy, especially post-crisis, such concerns do not appear to have a major impact on actual policy choices,” the paper says.

In an interview with RIJ, however, Cieslak noted that traders perceive that a Fed put exists, and dissenting voices on the FOMC have expressed concern that this perception encourages excessive risk-taking.

“If you believe that increased leverage is one sign of excessive risk-taking, there is some evidence of this going on in the broker-dealer sector before the 2008 financial crisis,” she said. “But we don’t see it happening after the financial crisis.”

Back to zero

At the end of 2018, Fed chair Powell should have stood up to President Trump and continued on the path of tightening that Janet Yellen had set. Instead, by lowering rates, the Fed reinforced a dysfunctional pattern. It also ensured another long interest rate drought for the guaranteed retirement products industry.

In order to provide retirees with annuities that have value, life/annuity companies need interest rates that are high enough and stable enough to give their investments in superior bonds a reasonable return. In December 2018, I thought we were approaching that sweet spot. Now I doubt that we’ll get there in my lifetime.

© 2020 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.