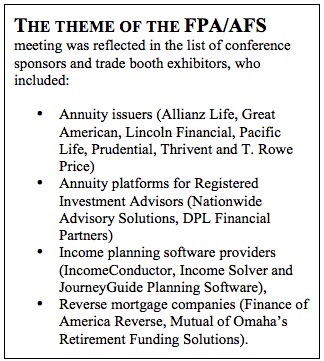

“Longevity” was the theme of the combined Financial Planning Association (FPA) and Academy of Financial Services 2019 annual conference last week. Some 1,800 Continuing Education credit-hungry advisers convened in Minneapolis to receive wisdom from some of the heavy-hitters of the retirement income space.

Wade Pfau, Ph.D., of The American College, was there to talk about the most popular types of annuities and about life insurance in retirement. David Blanchett of Morningstar, Curtis Cloke of Thrive Income, and Social Security expert Bill Reichenstein all presented their work.

A paper evaluating three approaches to “bucketing,” co-authored by Harold Evensky, was showcased. Retirement gurus Bob Laura and Bob Mauterstock discussed emotional aspects of investing and retirement. Yi Liu and Michael Guillemette presented a paper, “Does Risk Aversion Influence Annuity Market Participation.” (Yes, it does.)

Pfau, who is director of the Retirement Income Certified Professional program at The American College, offered FPA members a 45-minute tutorial on the three main types of annuities: income annuities, variable annuities and index annuities. Pfau has just published “Safety-First Retirement Planning,” a book that describes the synergies that can arise from combining annuities and mutual funds or exchange-traded funds.

In one of his examples, he showed that a life-contingent immediate annuity for a 65-year-old woman could produce $10,000 per year for life for about $172,915 at current rates. Using the 4% safe withdrawal percentage rule, $172,915 in savings would initially produce annual income of about $6,920.

Pfau also compared the annuity with a bond ladder. A 35-year ladder of risk-free zero-coupon bonds producing a safe $10,000 per year for 35 years would cost about $224,872.

Retirees could in theory buy the annuity and invest the $52,000 savings ($224,872 – $172,915) in stocks, raising their potential for long-term growth.

Like Pfau, speaker Curtis Cloke, the creator of the Thrive method of retirement income generation and the Retirement NextGen retirement planning software, generally follows the floor-and-upside income philosophy, which involves financing essential needs with guaranteed income sources and financing “discretionary” or optional needs as well as legacy goals with risky assets.

But, unlike the academic Pfau, Cloke’s career originated in the insurance sales world, which relies far more on emotion since it involves direct persuasion of clients. His presentation, while partly numbers-driven, was equally dedicated to the emotional dynamics of the annuity sales process and its frequent reliance on building enough trust in the adviser to culminate in the transfer of a large lump sum of money to purchase an irrevocable annuity.

Cloke summarized his philosophy as “Buy income and invest the difference.” He described his retirement income generation methodology as a combination of bucketing and floor-and-upside. It also emphasizes including the purchase of adequate long-term care insurance and health insurance.

A summary of David Blanchett’s presentation on the uncertainty of retirement start dates and its impact on savings targets and retirement income sustainability was published in last week’s edition of RIJ. You can find it here.

Bucketing, Social Security

Another presentation, by a team that included celebrity adviser Harold Evensky, involved comparisons between three bucketing methods and a systematic withdrawal plan as methods of retirement income generation. The team’s other members were Yuanshan Cheng of Winthrop University in South Carolina, who presented the findings, and Tao Guo of William Paterson University in New Jersey.

This team concluded that a time-segmentation bucketing strategy (where retirement was divided into three multi-year periods and specific assets are matched with the income liability during each period) generally outperformed a cash reserve bucket method (a two-bucket system with a cash reserve bucket and a total return portfolio) and a goal-based bucket method (where assets are assigned to specific expenses, such as travel or education for grandchildren).

In their analysis, the team hypothesized a 65-year-old with $2 million and a 30-year time horizon. The retiree’s assumed marginal tax rate was 33% and long-term capital gains rate was 15%. They assumed a real return on equities of 5.1% per year and a real bond return of 0.30% per year.

The time-segmentation bucket (with an initial five-year bucket of bonds, followed by a five-year 50% stocks/50% bonds bucket, and then a 10-year bucket of equities) produced a higher annual income and smaller potential loss than any of the three other methods.

In a well-attended presentation on Social Security, William Reichenstein reviewed all of the special situations that can make it confusing or complicated to decide when and how to file for benefits in an optimal way. His tips and warnings are too numerous to repeat here, but you can glean many of them from Reichenstein’s slides.

In one slide, Reichenstein showed that latent but lucrative claiming strategies still exist, even though regulatory reform has eliminated the famous file-and-suspend strategy made famous by economist/author Larry Kotlikoff of Boston College.

For instance, Reichenstein described a 68-year-old retiree (born before the cut-off date of January 1, 1954) with a 62-year-old wife, who files a restricted application for spousal benefits (half of her full benefits) when she files for her own earned benefits at age 62. At age 70, he files for his own benefit, which includes all deferral credits. Depending on life expectancy, that strategy can be preferable to the husband waiting until age 70 and the wife waiting until her full retirement age (66½) to file for benefits.

Planners and annuities

Mainly through Pfau’s and Cloke’s presentations, financial planners at the FPA/AFS conference received a strong, positive introduction to the role that annuities can play in a retirement portfolio. But, despite the strong attendance at those two sessions, it’s still not clear to what extent planners are amenable to recommending annuities to their clients.

Pfau and Cloke made cases primarily for the use of income annuities, and for the use of those annuities as substitutes for bonds in retirement portfolios. But life insurers, especially non-mutual life insurers, would rather sell variable, index or structured annuities, not income annuities.

Those types of annuities, especially if they have income riders, might be substitutes for bonds or certificates of deposit. But they are just as likely to be substitutes for equities, since they offer direct or indirect access to the equity markets. That difference could confound the insurers’ attempts to communicate with advisers.

Annuity issuers might consider changing the way they talk to advisers about annuities. Insurance companies, whose business involves assuming or buying risk, are inclined to portray risks, including the various retirement risks, as evils. But financial planners and investment advisers are more likely to regard risk as a positive.

For advisers and their clients, risk is the path to reward. It is something to be embraced—gingerly, perhaps, but embraced nonetheless. Pfau and Cloke seemed to understand that, and they emphasized the ability of annuities to add upside potential as well as downside protection to a retirement portfolio.

Insurers should take a cue from them, and try to sell annuities on the basis of greed, not fear. The switch may not come naturally to them, but it may be the best way to win the hearts and minds of advisers.

© 2019 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.