Bermuda’s pink sand beaches and reliably blue skies are lovely, but the tiny archipelago in the Atlantic has an added appeal. Its financial regulatory climate makes it a perfect domicile for the reinsurance operations of life insurers and, to an increasing degree, private equity companies.

Visitors from those companies are keeping Bermuda-based actuaries busy. An actuary at a global insurance broker and consulting firm, has seen a “doubling or tripling of business,” he told RIJ this week. He asked not to be identified by name and that his company not be identified because he wasn’t cleared to speak to the media.

“Reinsurance assets under management in Bermuda have grown from $300 billion to $700 billion in the past three years,” he said. “All the big insurance companies are here, and all the private equity companies are eyeing Bermuda. They want to take advantage of the economic nature of the Bermuda reserving requirement.”

Reinsurers are simply insurers for insurers—sharing the risks and rewards of the insurance business without the responsibilities and expenses of marketing, distributing and administering annuity contracts or life insurance policies.

An acceleration in the purchase of Bermuda-based reinsurance is the latest in a decade of maneuvers by life/annuity companies in the US to deal with low yields on high-quality bonds. The Fed’s low-rate policy since 2009, so nourishing for equities, reduces the investment yield they need to write guarantees and earn profits for shareholders.

If low rates are a kind of desert, Bermuda represents a palm-fringed oasis. Its financial regulators use Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). Under GAAP, estimates of annuity liabilities—what insurers owe to policyholders or contract owners—can be lower than under Statutory Accounting Principles (SAP), which insurers must follow when preparing financial statements for regulators in the US.

By purchasing reinsurance in Bermuda on their weaker US liabilities, US insurers can capture the benefits of this difference and improve their finances. They can set up their reinsurance arms in Bermuda and buy it from themselves.

In recent years, big private equity firms have stepped in. Insurers have always hired them to help manage their investments. But, increasingly, the big PE firms (also known as buyout firms or alternative asset managers) have established their own Bermuda-based reinsurers, have bought or reinsured blocks of life insurance or annuity business from US life insurers, and have even purchased US life/annuity companies through their Bermuda reinsurers. This allows them to issue insurance products, reinsure them, and manage the premiums—beyond the view, to some extent, of US regulators.

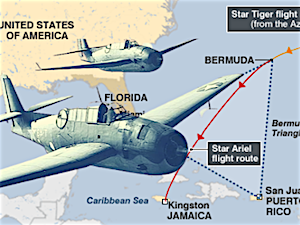

At RIJ, we’ve dubbed this powerful, vertically integrated arrangement the “Bermuda Triangle.” The steady pursuit of this strategy over the past decade is transforming the annuity industry, with implications for insurers, advisers and clients. On the plus side, the buyout firms have infused the life/annuity business with innovation and capital that it arguably needed. But in bending the annuity industry to their own purposes, are these firms bending it too far? The search for answers starts in Bermuda.

The world’s offshore reinsurance capital

Regulators and business development groups in Bermuda, a British territory located 650 miles east of Cape Hatteras, NC, have aimed at creating a Goldilocks financial regulatory framework—not too accommodating or too strict. It has a rare distinction: recognition by the European Commission as compatible with Europe’s “Solvency II” requirements for insurers and reinsurers. That recognition happened at the end of 2015, and it has helped build Bermuda into a major hub for reinsurance.

Bermuda tries to make reinsurance easy. The big accounting and insurance brokerage firms are there to help advise insurers who are new to reinsurance. It’s also a place where a reinsurer can report the investments backing its liabilities in “five or six pages” instead of the thousand-plus pages that a state regulator in the US might require, according to Tom Gober, a forensic accountant who studies and evaluates the assets backing insurance policies and contracts.

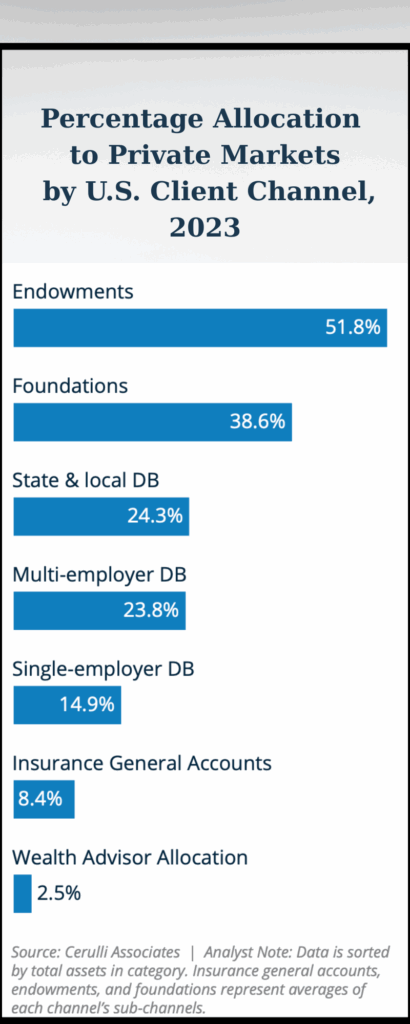

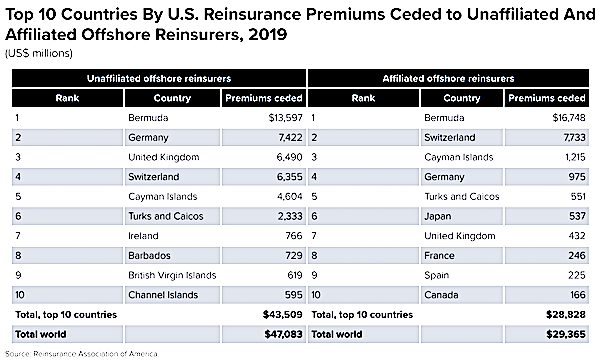

Bermuda-domiciled reinsurers accounted for about $30 billion of the $76 billion in US insurance premium that were reinsured by (“ceded to”) offshore reinsurers in 2019, the Reinsurance Association of America reported. (See chart below.)

“In recent months, the life and annuity market has experienced an unprecedented level of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) activity, as COVID-19 has accelerated an industry restructuring brought on by prolonged low interest rates and the emergence of private equity investor interest,” wrote a PricewaterhouseCoopers accountant in Bermuda Reinsurance magazine last June.

“Registrations over the past year have included private equity investors setting up their own reinsurers, existing players setting up sidecars to bring in third party capital and investment bank-backed transformation vehicles. This increase in activity is an acceleration of the trend in growth seen over the past decade.”

‘Regulatory arbitrage’

When a Bermuda-based reinsurer buys a US life insurer or reinsures a chunk of a US life insurer’s liabilities (or reserves), the reinsurer assumes the liabilities (money that will someday be returned to policyholders) of the US insurer, accompanied by sufficient assets (premium paid in by the policyholder) to back them up.

GAAP accounting, which Bermuda reinsurers use, allows them to estimate or assess those liabilities at a lower price than the US life insurer could using SAP accounting. Fewer assets are required to back up the same set of liabilities in Bermuda.

“Say that a person puts $100,000 into a fixed annuity,” a Bermuda-based actuary told RIJ. “The liability for the US issuer under SAP might be $98,000. For the Bermuda reinsurer it might be only $85,000. In the US, you have to reserve for the worst possible economic scenario. But there may be no actual scenario where you would have to pay the full amount.”

By moving a risk off the insurer’s balance sheet, reinsurance reduces the requirement for the “risk-based capital” that the insurer needs to hold. This capital is “released” for other purposes. The difference in the cost of the liabilities—$13,000 in the example above—doesn’t necessarily mean that the support for the liability is weaker, he noted.

Here’s how the Insurance Information Institute’s website describes the difference in accounting regimes: “SAP accounting is more conservative than generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), as defined by the Financial Accounting Standards Board, and is designed to ensure that insurers have sufficient capital and surplus to cover all anticipated insurance-related obligations.

“The two systems differ principally in matters of timing of expenses, tax accounting, the treatment of capital gains and accounting for surplus. Simply put, SAP recognizes liabilities earlier or at a higher value and recognizes assets later or at a lower value. GAAP accounting focuses on a business as a going concern, while SAP accounting treats insurers as if they were about to be liquidated.”

But most of the reinsurance deals in the Bermuda Triangle strategy are not plain-vanilla reinsurance, or even plain-vanilla offshore reinsurance. Today’s deals are more likely to involve “modified co-insurance” or “co-insurance with funds withheld.” These are highly complex, less transparent deals between a life/annuity company and its own captive or affiliated Bermuda-based reinsurer, or even between Bermuda-based reinsurer and a life/annuity company that it owns. These involve complex paper transactions that can produce accounting windfalls. Though too complex to address here, we’ll explore the financial benefits of these deals in the future installments of the series.

‘Convergence of demand’

These co-insurance deals are widely characterized as win-wins for private equity firms and for life/annuity companies. “There’s a convergence of demand from private equity firms on the buy-side and from annuity sellers on the sell-side to do something about in-force books that are producing less than ideal returns,” Tim Zawacki, an analyst at S&P Global Market Intelligence told RIJ recently.

“These transactions give the cedant [the life insurer reinsuring in-force blocks of annuities, for instance] access to a much wider array of higher-yielding assets that they can produce internally,” he said. “The asset manager can create investments for these portfolios that may drive higher yields than the insurance companies could achieve on their own,” such as private debt or securitized mortgages.

“This partnership between insurer or reinsurer and PE firm is beneficial for both parties,” wrote Phill Namara at Montaka, an advisory firm in Surry Hills, Australia, in a recent blogpost. “The private equity firms receive long-term capital with little redemption risk that they can invest and earn recurring management fees and performance fees, granted they abide by state insurance laws…

“On the other hand, the insurers or reinsurers benefit from being able to shed legacy liabilities from their balance sheet and [get] higher mixed investment returns from their increased exposure to the PE asset class. Further, they also benefit from presumably lower investment manager fees, given their capital is now managed within the same entity.”

Coming attractions

Tom Gober

Not everyone is so sanguine about these trends. In the fully articulated version of the Bermuda Triangle strategy, two or even all three pieces of the puzzle—the asset manager, the reinsurer and the life insurer—are controlled by the same company. Some, like the forensic accountant Tom Gober, are concerned that the offshore deals might be opaque, and lack the checks and balances that exist when unaffiliated counterparts are involved.

“While I have seen many different varieties of mechanisms used in affiliated, offshore reinsurance deals, all of those variations resulted in the same outcome: they create an appearance of new, extra surplus that would certainly not be allowed in the regulated insurance company – the ceding company,” Gober told RIJ.

Since the financial crisis, many life insurers, in response to the Fed’s monetary policy, have reached for yield by investing in alternative assets that some regard as riskier, including asset-backed securities such as collateralized loan obligations. The National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) recently reported that private equity-affiliated life insurers, on average, hold higher concentrations of such assets than does the life/annuity industry overall. That makes some observers worry about the potential for higher risk in the system, and the chance for future insolvencies.

There are also potential questions about fixed indexed annuities (FIAs), the product that private equity-owned life/annuity companies like to produce because the money stays in place for up to 10 years at a time. The PE firms call it, “permanent capital.” The lengthy terms give the asset managers time to invest in potentially high-yielding “illiquid assets,” like collateralized loan obligations.

But FIAs are controversial. The federal government twice tried (in 2007 and 2016) and failed to regulate them more closely, out of concern for their complexity and for a history of unsuitable sales by independent insurance agents. Misgivings about FIAs remain, especially among registered investment advisors (RIAs) and financial planners.

All of these developments are reshaping the annuity industry in ways that few distributors or advisers, let alone clients, are likely to appreciate. We’ll address them in future installments of the Bermuda Triangle series.

© 2021 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.