Private equity (PE) firms or “alt-asset managers,” in the opinions of many, have bestowed heavenly manna on the life/annuity industry during the past decade’s yield-famine.

In addition to buying several large and small life insurers outright, PE firms have relieved other life companies of capital-intensive blocks of annuity and life business, “released” surplus capital through reinsurance, used their loan origination skills to boost general account yields, and perked up crediting rates of indexed annuity contracts.

But the PE disruption of the staid life/annuity industry has also raised the interest of regulators, legislators, life/annuity executives and actuaries—enough so that LIMRA, the life/annuity industry’s market research arm, included a break-out session on “Private Equity and the Life Insurance Industry” at its 2022 Life Insurance Conference in Tampa this week.

Expert panelists included Tim Zawacki, research analyst at S&P Global Market Intelligence; Rosemarie Mirabella, a director at ratings agency AM Best, and Jason Kehrberg, an actuary at PolySystems Actuarial Software and Services and chair of the American Academy of Actuary’s Asset Modeling and Risk Task Force.

My takeaway: Few observers believe that PE-owned life insurers (or the life insurers that hire PE firms to run their money) are putting themselves or their policyholders at risk; on the contrary, most of those companies sport “A” ratings from AM Best. Most close observers also believe that current regulatory frameworks—though fragmented and playing catch-up with a fast-changing industry sector—are working.

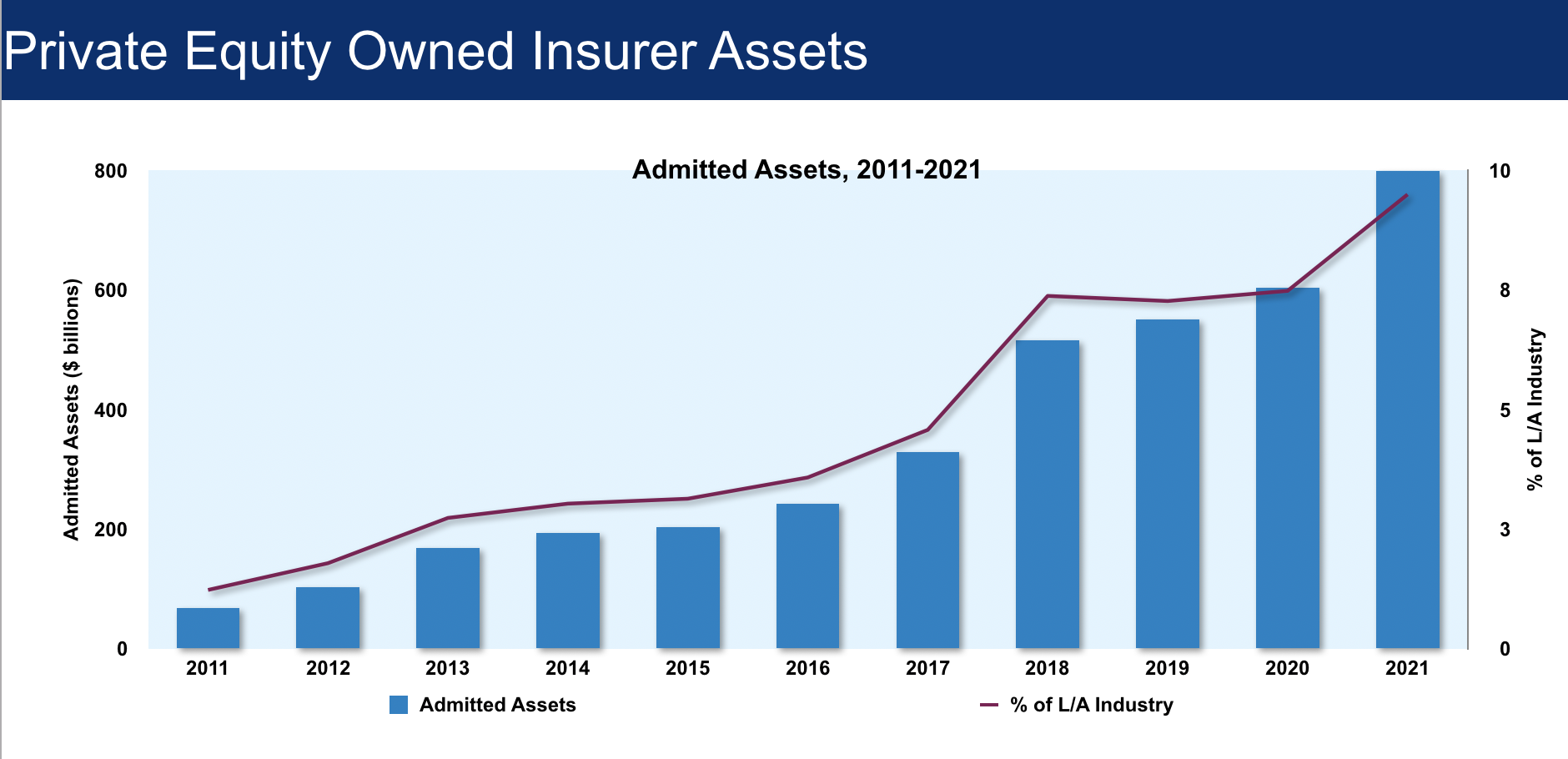

But private investments now account for some $800 billion of life company general account assets —10% of the industry total—and are rising, AM Best shows. Private assets like CLOs (collateralized loan obligations) tend to be opaque, complex and hard to price.

PE-led reinsurance arrangements use complicated “modified coinsurance” or “funds withheld” structures. Fixed indexed annuities, the raw material of private assets, are hard to understand. Transactions between subsidiaries of the same holding company can lack transparency or the equipoise that unrelated counterparties can bring to transactions.

Regulators and legislators (most recently New York’s Department of Financial Services and Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-OH) have joined the National Association of Insurance Commissioners in looking closely and asking questions about PE penetration of the life/annuity business. PE firms, after all, are now handling almost a trillion dollars worth of annuities, much of which represents the retirement savings of middle-class Americans.

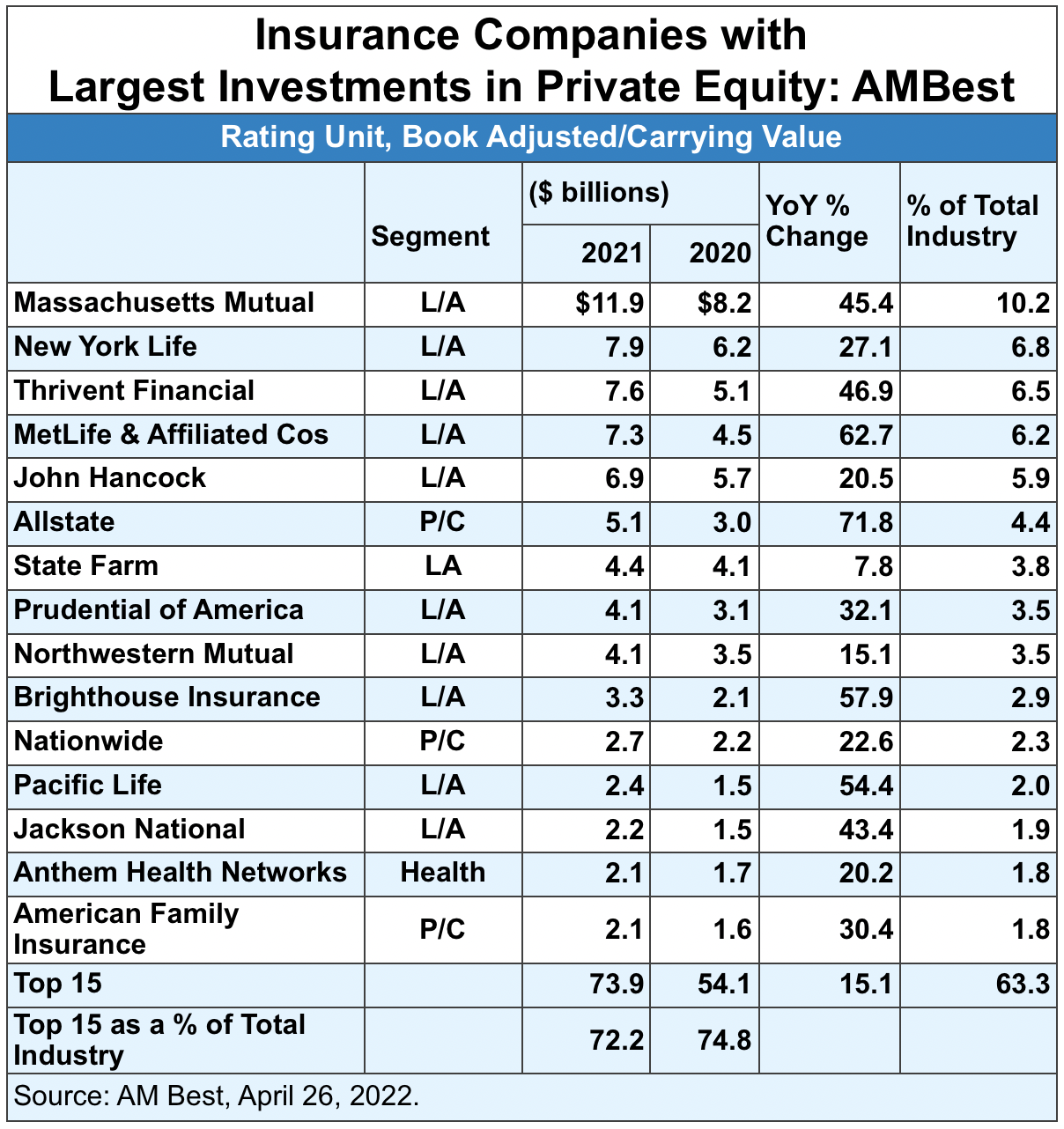

US-domiciled insurers with the highest book value of private equity investments in their general accounts.

‘Surprising’ risk-based capital levels

Mirabella

In her presentation, Rosemarie Mirabella of AM Best showed the acceleration of PE’s presence in insurance. “PE companies controlled only 1.2% of industry assets in 2011, now its up to $800 billion or about 10% of the life/annuity industry’s assets,” Mirabella said.

Why do investment companies like insurance assets so much? “They like the [fixed] annuity space because the embedded guarantees are modest relative to what they can earn on the asset management side,” Mirabella added. “Private equity is a duration asset class [with specific initiation dates and ending dates]. That gives companies ability to match liability to assets.”

“These companies have other advantages besides investment skills. They don’t have the pressure of legacy systems. They’re good on the digital side. They understand what it takes to leverage their business model. They have a lot of capability to support good returns.”

PE company purchases of insurance assets started slowly after the Great Financial Crisis, and then accelerated. “In the early years, from 2011 to 2016, we saw the ramping up and re-engineering of the investment portfolio by the PE firms,” she said. Yields and profits didn’t show much change until 2016. Then they started to climb—above the life industry, above the individual annuity composite, above stock companies overall.”

Mirabella said she first expected life insurers under PE control to run minimal RBC ratios (Risk-based capital). Instead, she watched their ratios climb and, by 2017, exceed the overall industry’s. “That was a surprise to me,” she confessed. “A lot of [PE] companies were coming in and buying capital-impaired insurers. I expected it to take them awhile to reengineer the business and increase the capital base.”

Source: AM Best.

‘Little choice but to optimize balance sheets’

In his slides, Tim Zawacki of S&P Global Intelligence also tracked the growth of PE firms in life insurance. Mergers and acquisitions involving US and Bermuda-based life-sector firms were close to $30 billion in 2021, the highest level in 16-years.

PE-linked entities accounted for 64% of the reserve credits taken for reinsurance in 2020 and 56% in 2021. The 2021 figure didn’t count Global Atlantic’s deal with Ameriprise, in the which the KKR subsidiary reinsured $8 billion in Ameriprise. The deal allowed Ameriprise to release $700 million in excess capital.

Zawacki cited these supply and demand factors in driving PE/annuity reinsurance activity in 2021 and 2022:

- A continued push by traditional carriers to reinsure their legacy liabilities

- An interest in acquiring or reinsuring variable annuities and universal life with secondary guarantees, in addition to fixed/indexed annuity business

- Organic growth from primary business [i.e., new fixed/fixed-indexed annuity sales] and flow reinsurance [instant reinsurance of newly issued annuity contracts]

- Demand from traditional life/annuity reinsurers for new business

- Demand among private equity-affiliated investment funds for a source of permanent capital

Zawacki

In an interview, Zawacki explained the growing demand for reinsurance. “From a competitive standpoint, for public companies to achieve the kinds of returns that equity investors expect, they have little choice but to optimize their balance sheets by engaging in these [reinsurance] structures.”

But today’s “modco” or “funds withheld” reinsurance arrangements, where an Iowa-domiciled life insurer might get credit for reinsuring annuities in Bermuda without giving up control of the assets, can be obscure. “If you have funds withheld, the deals become more difficult to analyze. It’s impossible for an outside observer to distinguish what is in a ‘funds withheld’ account and what is part of the general account investments. That’s one challenge with that structure.”

Are ASOPs up to the task?

Reinsurance isn’t the only complex piece of the PE/insurance phenomenon. The high-yield private equity and private credit assets that PE firms originate, including securitized bundles of leveraged loans, are difficult for actuaries to analyze and evaluate.

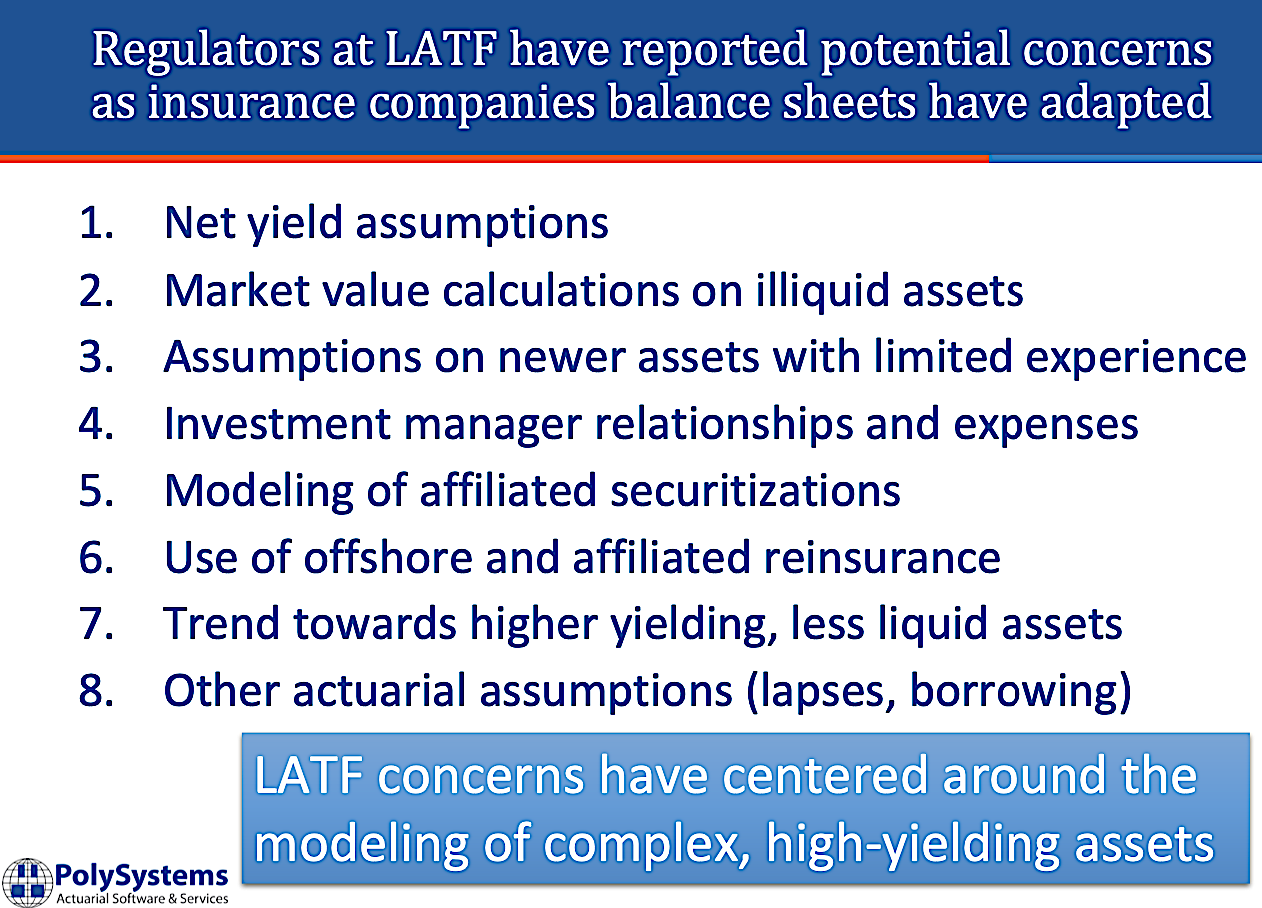

Jason Kehrberg, of PolySystems, said that members of the NAIC’s Life Actuarial Task Force have “potential concerns,” as described in the slide below.

Actuaries do have tools for analyzing high-yield products, such as the Actuarial Standards of Practice (ASOPs). Kehrberg shared a deep-in-the-weeds review of the ASOPs that might apply to actuaries’ analyses of CLOs and other complex investments. Whether those practices are sufficient for the challenge presented by today’s bespoke assets remains to be seen.

Kehrberg

The NAIC’s Life Actuarial Task Force has proposed a new Actuarial Guideline for Asset Adequacy Testing, he said. If adopted, this guideline would apply to “reserves reported this year-end to life insurers with general account actuarial reserves [i.e., liabilities] of $500 million or more and at least 5% of supporting assets composed of projected high net yield assets.”

Kehrberg defined a projected high net yield asset as a “fixed income asset whose spread over a comparable Treasury is greater than a prescribed BBB spread less a prescribed BBB- default rate” or “equity-like assets in the category of common stock for purposes of risk-based capital C-1 reporting.”

Lots of runway left

Driven by the almost universal demand for higher yields, higher fee revenue, and higher profits, the convergence of insurance and investments will likely continue, analysts say. Mergers, acquisitions and strategic partnerships between life/annuity companies and alt-asset managers will likely continue to be formed—though perhaps at a slower pace if US and world economy goes into an anti-inflation, post-stimulus recession.

Would a rise in prevailing interest rates slow down this trend, perhaps causing a shift by investors from indexed annuities to bonds or bond funds? Barring a steep economic downturn in 2022 or 2023, Mirabella didn’t think so.

“The PE-owned companies have been positioning themselves for years to take advantage of the eventual uptick in interest rates,” she said.“This trend will continue unless there are major, fundamental economic shocks that change the risk profile of private equity.”

Zawacki told RIJ that he looks forward to seeing the Federal Insurance Office’s (FIO) response to Sen. Sherrod Brown’s March 16 request for more information on PE ventures in insurance, to be delivered by May 31. There are many different aspects to those ventures, and the future of regulation in this area may depend on which aspect the FIO focuses its energy and attention on, he noted.

Will it focus, for instance, on the adequacy of the existing state-based regulatory framework? On the perceived arbitrage with offshore domiciles? Or at the pension risk transfer business? “There are a number of different ways this could go,” Zawacki said. “We would like to see them update the regulatory framework to the realities of the market.”

© 2022 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.