It’s a bit counterintuitive that U.S. life/annuity companies, which effectively borrow hundreds of billions of dollars by selling annuities to American’s older investors every year, would need to, or choose to, borrow tens of billions more from government-sponsored banks.

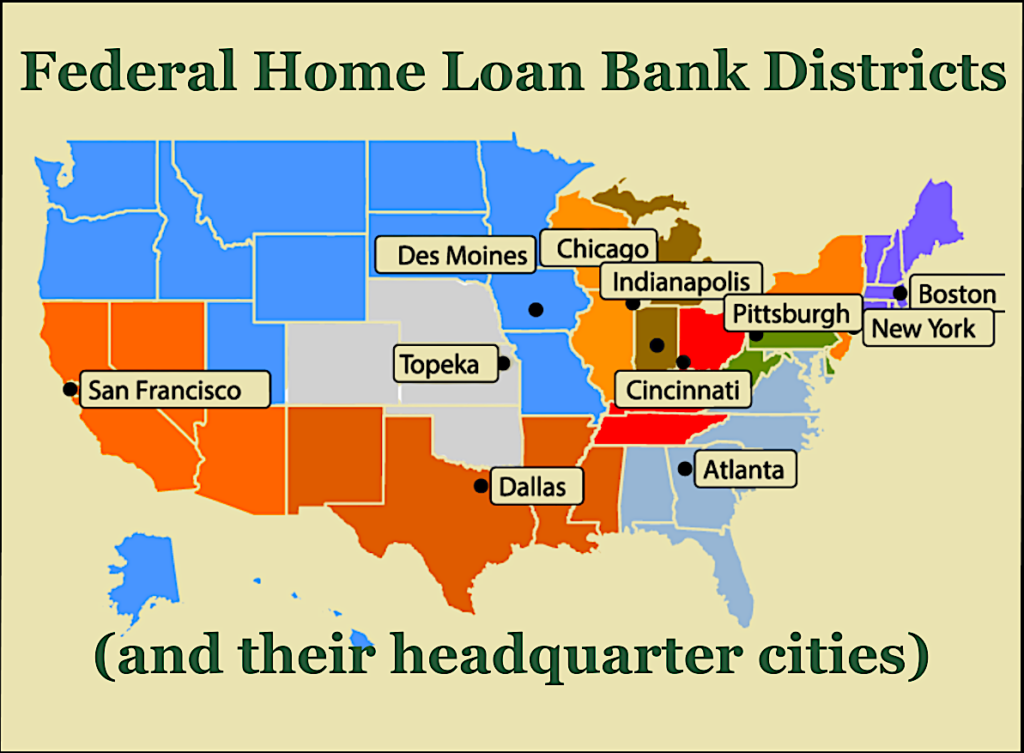

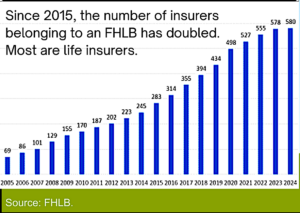

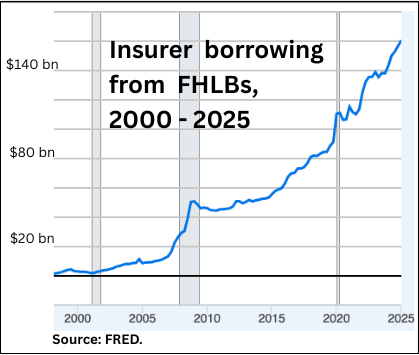

But they do. The banks are the Federal Home Loans Banks (FHLBs), that were set up by the federal government in 1932 to inject liquidity into a depressed mortgage market. As of the end of 2024, almost 600 U.S. insurers had $160 billion in outstanding FHLB loans, or more than 20% of the banks’ $726 billion in total lending. (In the first quarter of 2023, the FHLBs advances spiked to over $1 trillion.)

More than half that $160 billion went to just 17 large insurers, with Athene Annuity and Life the largest single FHLB borrower overall. (See chart at right.) Most of the others were, like Athene, among the 20 largest sellers of deferred fixed and variable annuities in 2024, with total combined individual annuity sales of about $176 billion (out of $434 billion in total retail annuity sales).

Why would so many major annuity issuers congregate at the FHLB windows? FHLB loans aren’t a free lunch. Insurers have to join an FHLB and buy stock in it in order to borrow from it. There are limits on the kinds of collateral they can post, and they need to “over-collateralize their loans.

But the borrowing costs are subsidized, the terms are flexible and, in recent years, the timing has been right. Lending rates are only slightly higher than the Secure Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR). In the past few years, insurers have used the money to take advantage of rising interest rates on new bonds and to grow their high-yield private credit businesses.

“Life insurers often use these advances as part of a spread arbitrage program where the advances are reinvested in higher-yielding assets,” according to a recent Office of Financial Research report.

Federal Reserve researchers also have identified FHLB loans as a component of what RIJ has called the “Bermuda Triangle” strategy. The strategy, pioneered by Athene more than a decade ago, typically involves an asset manager-owned life insurer that issues investment-like deferred annuities, reduces its capital requirements with the help of Bermuda-based reinsurance, and—the ultimate goal—maximizes its investment in risky, high-return private credit.

In the purest form of the strategy, the annuity issuer, the Caribbean reinsurer, and managers of the private credit (via collateralized loan obligations, or CLOs) are all—as in the case of Apollo, Athene Annuity and Life, and Athene Re—affiliates of the same holding company. Fed economists and others have described the Bermuda Triangle strategy as opaque, conflicted, and a potential hazard to the stability of the global financial system.

Biggest annuity issuers borrow the most

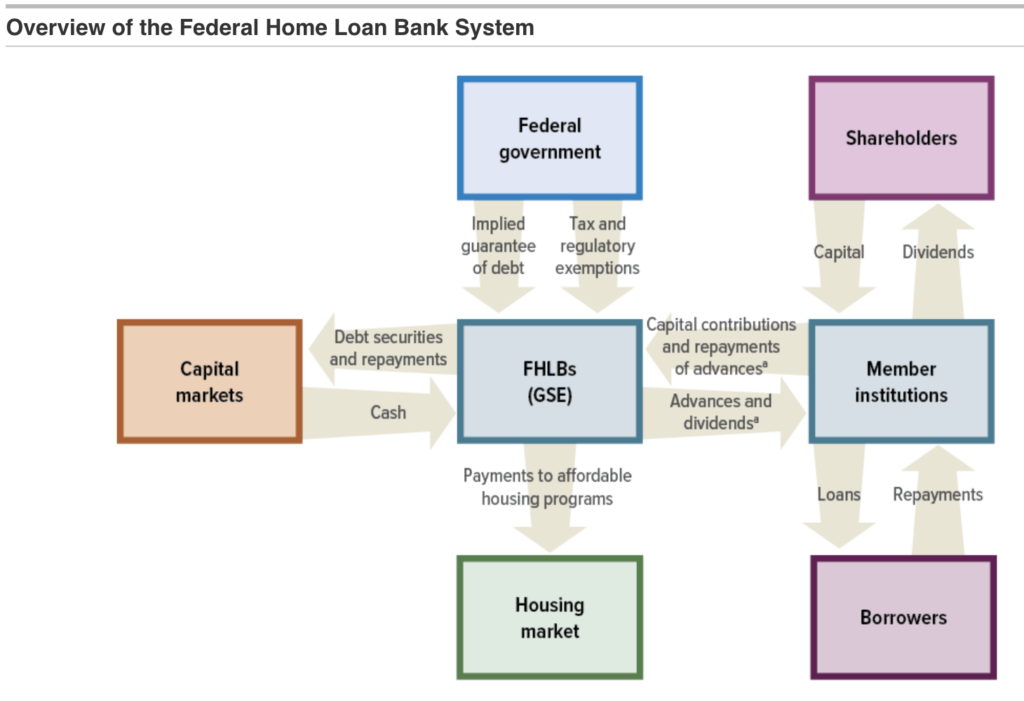

When banks need liquidity, they can go to the Federal Reserve. When insurers need liquidity, they can sell commercial paper in the wholesale money market or use short-term loans (such as repurchase agreements, or “repos,”) that they can roll over indefinitely. If they are stock-owning members of an FHLB, they can borrow large sums from it, using their residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) and other safe assets (like Treasury bonds) as collateral.

Until 1989, FHLBanks had few if any insurer members. Today, the biggest life/annuity companies are also among the FHLB’s biggest borrowers. Of the 6,500 or so FHLB members, most are banks or credit unions. About 580 are insurers; of those, over 90% are life companies. While less than 10% of the FHLB membership, insurers account for about 20% of FHLB loans (called “advances”). Insurers held a combined $160 billion in FHLB loans at the end of 2024, double their 2016 share.

[FHLB advances peaked at more than $1 trillion in the first quarter of 2023. Of that, insurers borrowed $140 billion. In the following year, insurers borrowed $160 billion. Indebtedness fluctuates as loans are repaid or rolled over.]

If you look at the lists of the top five borrowers from each of the 11 FHLB branches, you’ll find 17 life insurers accounting for more than $80 billion in advances as of the end of 2024, according to the FHLBs’ year-end 2024 report. The single biggest FHLB borrower for 2024 was Athene Life and Annuity. It had $15.6 billion in outstanding funding agreements with the Des Moines FHLB and $17.2 billion as of March 31, 2025.

If a life insurer sells a lot of annuities, there’s a good chance that it’s also major customer of its regional FHLB. Athene sold the most annuities in 2024 ($40 billion) and the most in the first quarter of this year ($9.5 billion). Other top annuity sellers in 2024—Corebridge Financial, Equitable, Jackson National, Lincoln Financial, and Massachusetts Mutual—were all among the major FHLB borrowers.

While these FHLB borrowers (except MetLife) all sell retail annuities, they don’t all sell the same types of annuities. TIAA sells group annuities to retirement plan participants. Equitable was the top seller of registered indexed-linked annuities (RILAs, a type of variable annuity) in 2024, at $22.4 billion. Athene and MetLife are both active in buying corporate defined benefit pensions.

Jackson National sells both traditional variable annuities (tax-advantaged bundles of mutual funds) and RILAs. Massachusetts Mutual, one of three mutual insurers on the FHLB list, was the second-biggest seller of fixed annuities in 2024 (after Athene) and ranked third in overall sales (after Athene and Corebridge Financial).

Five of the major FHLB insurer/borrowers—Athene, Delaware Life, Equitrust, and Security Benefit Life of Denver—are asset manager-driven insurers that practice the Bermuda Triangle strategy. Massachusetts Mutual is one of only three mutual insurers, beside Thrivent Financial and United of Omaha, that borrows significantly from the FHLB. It too sells fixed indexed annuities, owns a Bermuda reinsurer, and works closely with alternative asset managers.

The costs and benefits of FHLB loans

If annuities are insurers’ source of retail borrowing, FHLB loans represent borrowing at the wholesale level. The money comes in bigger chunks, the borrowing costs are lower, and the loans are “fungible.” FHLB loans appears among an insurer’s liabilities, often as “funding agreements” but it doesn’t need to be applied to real estate-related investments. Insurers don’t need to sell long-term assets to obtain FHLB loans.

Obtained through the sale of funding agreements (akin to guaranteed investment contracts, or GICs), FHLB loans can be obtained without the acquisition costs—commissions—that are the steep price of gathering revenue through the sale of annuities. FHLB loans count as liabilities on the insurers’ balance sheets, they aren’t capital-intensive.

Because FHLB loans are implicitly backed by the U.S. government, the loans are cheap. As of a June 27, the lowest current cost for an FHLB loan was 3.82%, the rate on three-year money, according to a spreadsheet of historical FHLB rates. The daily reset (floating) rate was 4.487% overnight rate. For comparison, the SOFR (Secured Overnight Funding Rate) on June 27 was 4.40%. Maturities range from one day to 30 years, and terms include “fixed- or floating-rate pricing, prepayment, and structured options,” according to a 2024 Wellington Management white paper on the topic.

Though they represent only a fraction of insurer liabilities, FHLB loans are more liquid and potentially more versatile than other reserves. Life insurers use them “to fund a merger or acquisition, meet regulatory requirements, and serve as a working-capital backstop,” according to Wellington Management.

Those assets include the tranches in CLOs that insurers increasingly buy, often from the same asset managers who own them or partner with them.

“Insurers also use FHLB loans to manage and mitigate interest-rate and other risks, optimize risk-based capital (RBC), reduce cash drag, meet social goals, supplement ALM (asset-liability matching) duration, and arbitrage collateral. … Insurers may borrow funds to lock in reinvestment rates and extend the duration of existing investment portfolios, or to fill liability maturity gaps and tighten ALM duration.”

To join one of the FHLBs, institutions borrowers buy stock in their regional FHLB, and top up their FHLB stock holdings when they borrow. “To capitalize advances, borrowers must purchase activity-based FHLB stock in addition to the stockholdings required for membership,” Wellington Management said. The shares pay dividends that further reduce the rate that insurers pay for the loans.

Insurers collateralize their FHLB loans with the real estate-related assets they already hold as reserves against annuity liabilities. They must “over-collateralize” and take a “haircut” (borrow less than 100% of the value of the collateral) when borrowing. The haircuts vary, depending on the underlying collateral.

FHLBs demand “housing-related” assets and other safe investments as collateral for their loans. That includes U.S. Treasuries, agency debt, agency and non-agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS), commercial MBS, whole first mortgages, housing-related municipal bonds, cash, and deposits in an FHLB can all be used as collateral.

Eligible collateral “must be single-A rated or above and housing-related,” according to Wellington Management. Corporate bonds, private debt, and equities can’t be used as collateral. FHLBs insist on having the collateral physically delivered to them, a measure that helps increase the safety and therefore the costs of the loans.

When the FHLB lends to banks, it has a “super lien” on the collateral, which in case of an insolvency the FHLB claims are senior to the banks’ other creditors. It’s apparently never been clarified—the situation has never arisen—whether the FHLB’s claims supersede the claims of policyholders when an insurer becomes insolvent.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Protests from consumer groups

The FHLBs have been accused of doing more to help their benefactors—the institutions that own their non-tradable stock—than to help their supposed beneficiaries, the low- and middle-income Americans who can’t find an affordable home to buy or apartment to rent.

FHLB’s mission is to push liquidity into the mortgage market and stimulate investment in real estate. It does that by contributing at least 10% of its own annual profits to affordable housing projects and by lending against real estate-related collateral.

According to the letter of the law and conventional wisdom, that’s what happens. “Insurance companies, through these investments, are liquidity providers for the MBS market, which in turn generates cost savings for individual homeowners,” according to Wellington Management.

But the banks pay out more in dividends to shareholders than they contribute toward home ownership. In 2024, the FHLB earned $6.36 billion and paid out $856 million to housing programs (13.5%). That’s more than the minimum required but short of the FHLB’s stated goal of 15%.

That amount is “a drop in the bucket compared to the country’s housing supply needs and is insultingly small,” wrote one critic in 2024. “It is fundamentally difficult to square these loans with the network’s purpose of boosting the country’s mortgage market.”

Government research groups such as the Congressional Budget Office, the Congressional Research Service (CRS), the Office of Financial Research have echoed those complaints in recent years. “Whether the FHLB system specifically facilitates mortgage funding or simply provides wholesale funding at below-market rates is debatable because the funding of assets is a fungible activity,” wrote a Congressional Research Service analyst in a 2024 report.

The FHLB’s own Report to Congress in 2025 conceded that “many member institutions eligible to join the FHLB system may not be principally engaged in residential mortgage finance, calling into question the extent to which FHLB advances subsidize the funding of mortgages or the funding of member institutions’ asset portfolios in general.”

The Bermuda Triangle connection

A handful of Federal Reserve economists have studied the change in business models of certain large life/annuity companies since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008. Several have concluded that FHLB loans are a component in the adoption of “shadow banking” as the main business of major annuity issuers. (“Shadow banks” are defined as wholesaler lenders outside the more heavily-regulated retail lending markets.)

Offshore reinsurance is another component of the business model. According to a 2023 paper, “Are Insurers the New Shadow Banks?,” by analysts in the Research and Statistics Division of the Federal Reserve Board:

Life insurers’ shadow banking businesses combine three types of entities in a triangular organizational structure. The first type of entity is US-domiciled life insurance companies. Large life insurers with an investment-grade rating can also tap wholesale funding markets by issuing nontraditional insurance liabilities to institutional investors. These liabilities include funding agreement-backed securities (FABS) and Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) advances collateralized by funding agreements. The second type of entity is captive reinsurers located in Bermuda… The third type of entity in the triangular organizational structure is an asset manager that originates, acquires, and manages corporate loans.

In this view, major annuity issuers that work closely with alternative asset managers (Apollo, Ares, Blackstone, KKR, etc.) now focus on obtaining inexpensive liquidity by selling low-risk deferred annuities and borrowing from FHLBs in order to finance their high-yield loans to high-risk borrowers.

It’s a lucrative trend—but one that worries the federal government’s Financial Stability Oversight Committee. According to the FSOC’s 2024 report, “Life insurers’ growing use of nontraditional liabilities, such as greater borrowing from capital markets and Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBanks), could raise concerns about their ability to manage cash flows in times of stress, as well as concerns about their growing dependency on such credit facilities to sustain spread-based product lines.”

© 2025 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.