A century ago, Robert Frost wondered if the world would end in fire or ice. Today, Americans with money wonder if their world might end in, say, a new technology boom or in a drawn-out period of secular stagnation, with low profits, low real yields and low returns.

“Saving and Retirement in an Uncertain Environment” was, fittingly, the theme of the Pension Research Council symposium at Penn’s Wharton School in Philadelphia this month. Its agenda: to “explore how the weak performance of capital markets predicted over the next several years will shape pension, savings and decumulation plans.”

It was a bad news, better news story. The bad news: With a rising dependency ratio (too many old people per worker), equities at historically high P/Es, and T-bonds with zero real yields, investment returns appear to have nowhere to go but down.

The better news from the PRC conference: Inflation will be low, Boomers will work longer, and unforeseeable breakthroughs in technology may, deus ex machina, offer new avenues of 1990s-like GDP growth.

There was a mix of industry and academic voices at the conference. Teams from PIMCO, Vanguard, AQR Capital Management, State Street Global Advisors, Allianz Asset Management all presented papers, along with economists from Boston College, Goethe University, George Mason University, the Brookings Institution, The American College and Wharton.

The situation: Low rates

In his presentation, Raimond Maurer of Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany, where safe assets currently offer negative yields, assumed annual real returns of a 60/40 portfolio going forward at either zero percent or 2% interest rates.

Vanguard researchers were more optimistic, predicting 5.5% returns. “For the 10 years through 2026, we estimate that the median return for [a 60% allocation to global equities and 40% to global bonds] will be almost three percentage points lower” than the 8.5% annualized return of the prior 90 years, said David Wallick of Vanguard’s Investment Strategy Group.

Antti Ilmanen of AQR said, “In the 1900s, the average returns for a 60% stocks, 40% bonds portfolio was 5%. But that has fallen to 2% to 2.5% in recent year. It hasn’t just been bonds. The returns on stocks have been declining too. The low discount rates are making returns on all long investment low at the moment.”

The low-returns ship has already sailed, inferred Michael Finke of the American College. When average P/E ratios were as high in the past as they are today (over 25), average annual real equity returns over the next decade were only 50 basis points. He suggested 2% real returns for a balanced portfolio as a “realistic” expectation for the next decade.

For savers, the combination of lower returns and longer life expectancies means that retirement is going to cost much more than it used to. To people on the verge of retirement it means, as Finke put it, that $1 of guaranteed lifetime inflation-adjusted income (i.e., an annuity) now costs about twice today as much as it did, in real terms, in 1982, the year when the stock-and-bond boom started.

What to do about it?

A number of responses to the looming period of low average returns were suggested. On the one hand, people can accept low-returns and work longer, save more, and spend less. Or they can shoot for higher net returns by managing risk better or cutting costs. Or you can capture the benefits of longevity risk pooling, by using Social Security efficiently or buying a private annuity.

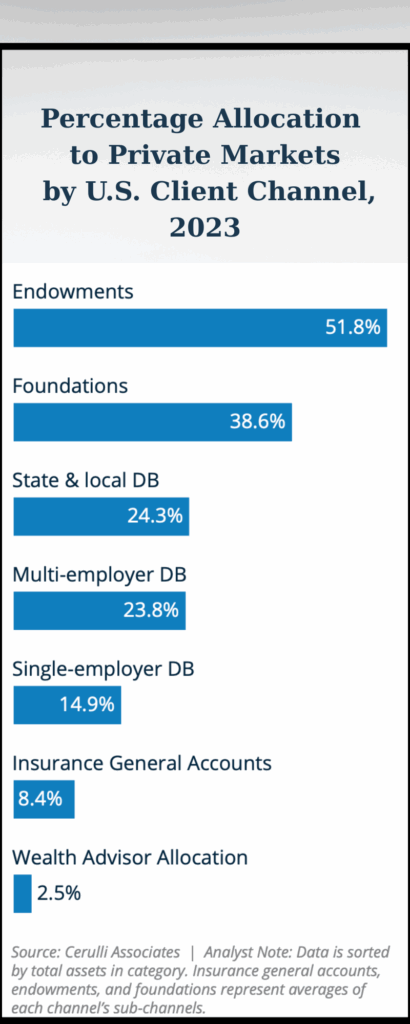

Alternatives. One solution is to not accept low returns fatalistically but to get people to invest smarter—perhaps by adding alternative assets in the target date funds in which millions of 401(k) plan participants invest by default. This was suggested by Antti Ilmanen, a principal at AQR Capital Management, the firm started by outspoken hedge fund billionaire Cliff Asness.

Ilmanen’s suggestion was to diversify TDFs with commodities, “benign” forms of leverage, more global equity and bond exposure, and long-short strategies. (These are AQR’s own practices.) If executed well, he said, these tactics and strategies can produce better long-term returns without greater risk than TDFs already carry.

Lower costs. A very different response was to raise returns by lowering costs. The efficient-market, do-it-yourself enthusiasts from Vanguard maintained that you have to take more risk to get better returns and that the only reliable way to increase returns in a low-return world is to reduce costs.

“Looking forward, you can try to maintain your same level of return with a lot more risk, or you can target the same level of risk and lower your expectation of income,” said Vanguard’s David Wallick, whose presentation was titled, “Getting More from Less: Three Levers for a Low-Return World.”

“Clients want this problem pushed out into the future. But not understanding the problem won’t solve it. That’s the problem with turning to active management and private alternatives—you’re just hoping that someone else will deal with the problem instead of you.”

Delaying Social Security. If your biggest fear is running out of money before you die, then, in a low-return world, you can reduce that risk by claiming Social Security benefits later, suggested Raimond Maurer of Goethe University, who presented a paper co-authored by colleagues Vanya Horneff and Olivia Mitchell, director of the Pension Research Council.

They suggested building a bridge to Social Security with other savings. In their research, they calculated that a middle-class person who retires at age 62 would be better off covering his costs out of personal savings for the next four years and claiming Social Security at age 66 than claiming Social Security at age 62 and preserving his personal powder dry.

The reason is that, thanks to longevity risk pooling, a person’s Social Security benefits will grow at a faster rate (between ages 62 to 70) than their personal bond portfolios will. In Maurer’s hypothetical example, a mass-affluent 62-year-old man would get $15,000 a year from Social Security immediately but $20,000 a year at age 66.

Assuming that the man would need $25,000 a year for expenses, Maurer calculated that if he delayed Social Security until age 66, spent $25,000 a year (out of his $200,000 in savings) until and spent $5,000 a year thereafter, his risk of running out of money at age 87 (average life expectancy) would drop from 100% to 7% (given a 2% real return on bonds).

Maurer noted that, in addition to working longer, a low-rate environment will discourage people from saving as much on a tax-deferred basis. “In a low interest rate environment, people save less, and save less in 401(k) plan. They will save less in tax-qualified plans and more outside tax-qualified plans. They will also finance their consumption in retirement by drawing down their 401(k) savings sooner and working longer,” Maurer said.

No one knows anything

Of course, no one knows what the future will bring. In terms of prognostication, economists have a poor track record. If Social Security benefits are cut and people have to save more privately for retirement, or if the stock market crashes and the equity premium surges to its full capacity again, or if a new and unforeseen technology creates a new range of investment opportunities, or if the U.S. embraces immigration to supplement the workforce, then most of today’s assumptions will go into the shredder.

If past performance predicts anything, it’s that the future brings irony, unintended consequences, weird feedback effects and resistance from vested interests. Solutions that serve the few may backfire if practiced by the many.

“Working longer may be the only effective aggregate solution,” said John Sabelhaus, an economist at the Federal Reserve. Richard Fullmer of T. Rowe Price said that, as a practical matter, changes in assumptions about future returns will trigger a lot of expense information technology updates at fund companies. Emily Kessler of the Society of Actuaries said that working longer is more often an option for the wealthy than for the under-saved middle-class.

William Gale, director of the Retirement Security Project at the Brookings Institution, observed that people generally choose to save a lot when high interest rates reward them for saving; it would be novel for people save even more because rates are low.

“Normally, we talk about how savings should respond positively to higher returns,” he said, echoing Maurer’s comments above. “Now the optimal response is to save more in response to lower returns. That’s assuming a very large saving inelasticity. We’ve departed from usual conversation.”

© 2017 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.