Here’s a true story.

Six years ago, a 74-year-old woman died suddenly. Her grieving husband couldn’t bear to live in the two-bedroom condo they’d shared since they became empty-nesters two decades before. A newer, sunnier condo in a nearby development appealed to his need for change.

The new condo with its glittery granite counters seemed beyond his means. But by selling the old condo, putting two-thirds down on the new one and using a reverse mortgage to pay off the balance of his new 30-year mortgage, he was able to trade up and still live mortgage free.

This man, who happens to be my father, doesn’t exactly fit the reverse-mortgage stereotype. He’s not a destitute widow determined to die in the family home. He’s an attorney who spent “not wisely but too well” for most of his life and retired with lots of home equity but not quite enough savings.

My father’s experience came to mind recently during a conversation with Jeff Lewis, chairman of Generation Mortgage Company (a unit of New York-based Guggenheim Partners that writes about $100 million worth of federally-insured Home Equity Conversion Mortgages a month), who tried to convince me that reverse mortgages aren’t just for the poor and the desperate.

Reverse mortgages will undoubtedly be a piece of the retirement income puzzle for many Boomers, but they’re still stuck with a shady reputation. That comes partly from the sector’s unregulated youth. It also comes from the fact that, like life-contingent annuities, reverse mortgages “smell of death.” Death, in the guise of mortality tables, hovers over the calculation of the payout, just as it does with SPIAs. It’s as if the Grim Reaper joins the attorney, broker and borrower at the big mahogany table on closing day.

Lewis tries to dispel that stigma. And, since his company is one of the few reverse mortgage firms trying to sell jumbo reverse mortgages, which means loans that are based on more than $625,500 worthy of equity and are not government guaranteed, he also tries to sell the idea that “equity release,” as the British call reverse mortgages, is good even for the wealthy.

Only six percent of Americans plan to use reverse mortgages. But “this shouldn’t be a niche product,” Lewis told RIJ. He doesn’t claim that reverse mortgages are cheap (the interest on jumbo loans can be above 8%), or that it’s easy for people to relinquish control over what may be their single most valuable asset, or even that reverse mortgages represent a windfall to the borrower. He does argue fairly persuasively, however, that they can quickly make more onerous obligations go away.

For instance, Sandwich Generation members who are making their parents’ mortgage payments could theoretically eliminate that expense with a reverse mortgage while keeping the parents in their home.

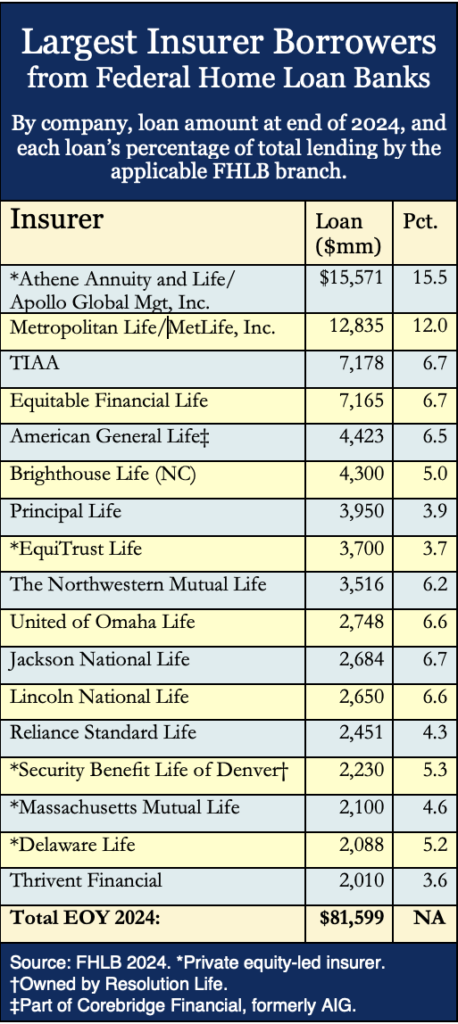

“I was talking to bankers at the Federal Home Loan Bank recently,” Lewis said. “Their demographic is 40-something and 50-something. I asked, ‘How many of you have a parent with a reverse mortgage?’ No one raised his hand. Then I asked, ‘How many of you are sending money to a parent to help pay for their home?’ Three quarters raised their hands. I said, ‘You’re buying your parent’s house over time. What’s your cost of money?’”

He also touts HECMs for short-term use. When set up as lines of credit, he said, reverse mortgages can make more sense than conventional home equity lines of credit. For instance, a 70-year-old person with a paid-for home worth $400,000 might qualify for (net of $15,000 in fees) a $235,000 line of credit whose unspent balance earns interest and which can’t be revoked or changed if home values fall, as they have since 2008. (The money can also be taken as a lump sum or income stream, or some combination thereof.)

But most of the people who use HECMs are, in fact, desperate. A ton of high-interest credit card debt has followed them into retirement, and using a reverse mortgage line of credit instead of tax-deferred savings to pay off the balance on the cards can be the lesser of two evils. “Most clients are using reverse mortgages to make other problems go away,” Lewis said.

This week, it got cheaper to set up a HECM line of credit when the Housing and Urban Development department announced the new “HECM Saver.” With a HECM Saver, seniors can’t borrow as much as they can under the standard HECM. (The difference is 10-18%.) But, because the loan is smaller, the upfront mortgage insurance premium drops to just 0.01% of the loan amount, from 2%.

Both HECM Saver and HECM Standard borrowers must pay an ongoing annual MIP of 1.25%, assessed monthly. On the HECM Standard loan, that represents an increase from the previous charge of just 0.5% per year; the hike reflects the expected continued weakness in home values. But seniors can get a bigger HECM Standard loan under the new rules, because the higher insurance premium allows lenders to use rates as low as 5%.

“This is for smart people, not just destitute people,” Lewis said. “Most people, when they do it, love it. There’s an emotional aspect to the resistance. You have a lot of older people who have always looked at their house as a savings bank, not like an ATM, and a reverse mortgage goes against that mindset. It feels a little like a stigma to them.

“But it comes down to, would you rather have the money or not? The reality is that, in the aggregate, Baby Boomers don’t have enough money in liquid retirement accounts to support themselves in their old age. With a reverse mortgage, they can buy 20 years of peace of mind.”

© 2010 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.