An Industry Haunted by Its Own History

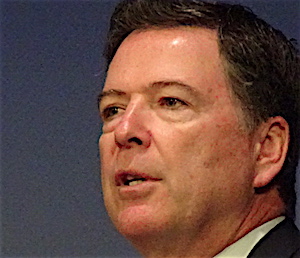

The ghost of demutualization haunts much of the annuity industry today. But that topic was not on the agenda of the annual LIMRA conference in New York earlier this week (Photo: Former FBI director James Comey, the keynote speaker at the conference).