Largely as a consequence of the pandemic, trillions of dollars have been flowing out of the Treasury’s coffers. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects the federal budget deficit for 2020 alone will exceed $3 trillion, three times higher than pre-pandemic estimates. Meanwhile, President-elect Joe Biden has suggested that trillions of dollars more should be spent to deal with the pandemic and then to address many of the nation’s social needs that will continue to exist beyond the current economic slowdown.

To determine how the longer-term budgetary effects of the pandemic have been playing out so far, and how similar pandemic-related expenditures might also affect the long-term direction of government spending, we compare the CBO’s September 2020, mid-pandemic, projections of real dollar changes in 2030 versus 2019 under current law to what CBO projected pre-pandemic in January 2020.

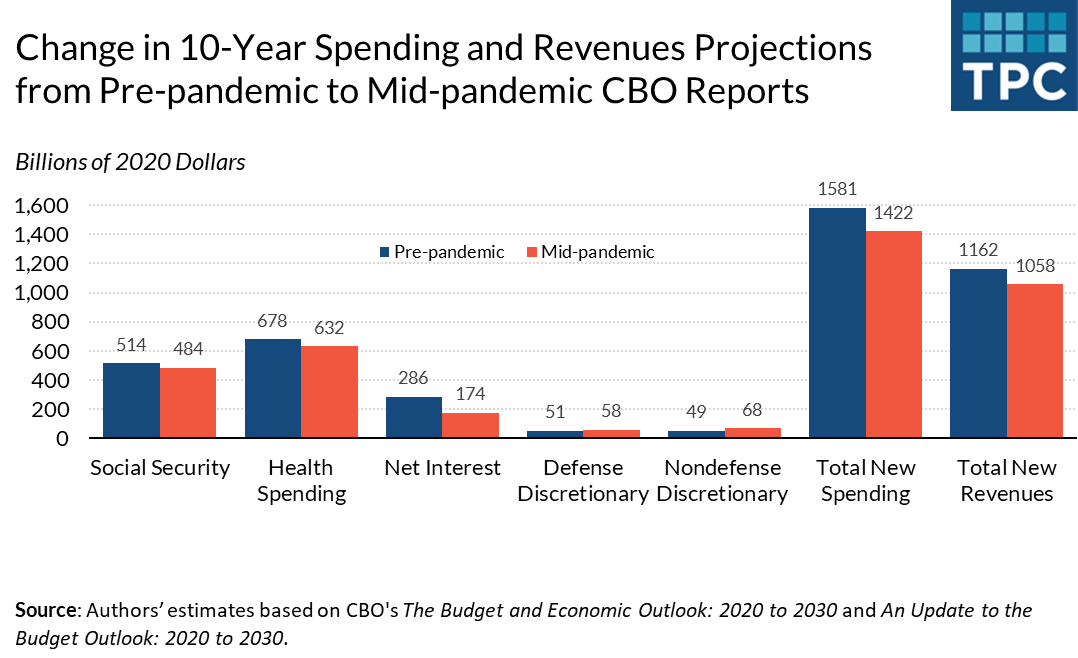

For the most part, we see fairly modest differences in budget forecasts of where increases in future spending would occur. Almost all of the pandemic-related boosts in spending are temporary, and the long-term trends remain dominated by the growth patterns that Congress and previous presidents had already built into the law, not by long-term societal needs and inequities highlighted by the pandemic.

The one exception is for interest costs. They still rise significantly under the September 2020 projections, but by about $100 billion less than in January 2020, largely reflecting CBO’s forecast of a lower interest rate environment due to Federal Reserve policy and the effect on saving and investment of a world-wide economic slowdown.

Comparing the mid-pandemic to the pre-pandemic forecast, lower interest rates would more than offset the additional interest costs associated with higher levels of debt, resulting in overall lower federal debt service as late as 2030. To be clear, lower interest costs due to a world-wide slump and slower projected economic growth are not good news.

Until recently, a growing economy would provide enough revenue to give a president significant leeway to chart new paths for spending. Such opportunity will likely elude President-elect Biden, however. When 2030 is compared to 2019, Social Security, health, and interest on the debt alone are projected to comprise 91% of the total real spending growth of about $1.4 trillion.

These three sources of additional costs would absorb 122% of the total revenue growth of about $1.1 trillion, assuming current law would remain unchanged after September 2020. Already this 122% figure is an understatement of what is likely to occur over the coming decade, as the new, largely temporary COVID-19 relief adopted in late December, along with the relief likely to be enacted in early 2021, will add to longer-term interest costs, assuming rates don’t fall further.

Moreover, President-elect Biden made campaign promises to increase taxes only for those with very high incomes. That implies that, unlike CBO’s measure of current law, he could feel compelled to accept a lower “current law” revenue base by extending the middle-class individual income tax cuts included in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) that are scheduled to expire after 2025.

Under January pre-pandemic projections, Social Security, health, and interest on the debt would constitute a very similar 94% of the total growth in spending and 127% of the total growth in revenues.

Although annual deficits by 2030 are large and growing, they remain close to the pre-pandemic projections. Of course, the accumulated debt will be much larger than formerly predicted. Thus, so far, the long-term impact of the pandemic and the nation’s responses to it reinforce and accelerate pre-existing budgetary trends, both in terms of overall spending projections and ever-larger gap between revenue and those expenditures.

President-elect Biden’s first priority will be to address the pandemic and the short-term economy, thus further increasing government spending. The open question: Once the pandemic is controlled, how will Congress and the incoming President adjust long-term spending and tax policy?

Higher debt levels alone may make it harder for the President to shift the nation’s fiscal path. Yet, absent significant reductions in the built-in growth rates in health and retirement programs, a substantial increase in revenues, or both, our current fiscal trajectory will increasingly hamstring the nation’s ability to address other priorities.