It’s been well documented that many older workers approaching retirement have only modest retirement savings. As a result, middle-income pre-retirees can’t afford to make big mistakes regarding how to deploy their retirement savings and build a retirement income portfolio.

Pre-retirees will need to make critical decisions that help them squeeze the most retirement income from their financial resources over a potentially long retirement. Studies have shown that they often feel uncertain about these decisions; economic turmoil, such as the downturn caused by the pandemic of 2020, only serves to increase their uncertainty.

Steve Vernon

Two recently published research reports prepared by the Stanford Center on Longevity (SCL), in collaboration with the Society of Actuaries (SOA) provide valuable insights into these decisions. These reports identify and analyze a straightforward retirement income-generating strategy that can work effectively for most middle-income retirees and can be implemented using virtually any traditional IRA or 401(k) plan.

It’s called the Spend Safely in Retirement Strategy, or the “Spend Safely Strategy” for short. One of these reports—Viability of the Spend Safely in Retirement Strategy—develops a decision framework that pre-retirees can use to make critical retirement decisions, including how to build their portfolio of retirement income. From this decision framework, here are the five most important decisions regarding retirement income that most middle-income pre-retirees should address:

- When and how to retire (whether to work part time for a period of time)

- When to start Social Security benefits

- How to deploy retirement savings to generate retirement income

- Which living expenses to reduce in order to live on less income in retirement

- Whether to deploy home equity by realizing capital gains and reinvesting the proceeds to generate

retirement income, or by purchasing a reverse mortgage

Decision #1: When and How to Retire

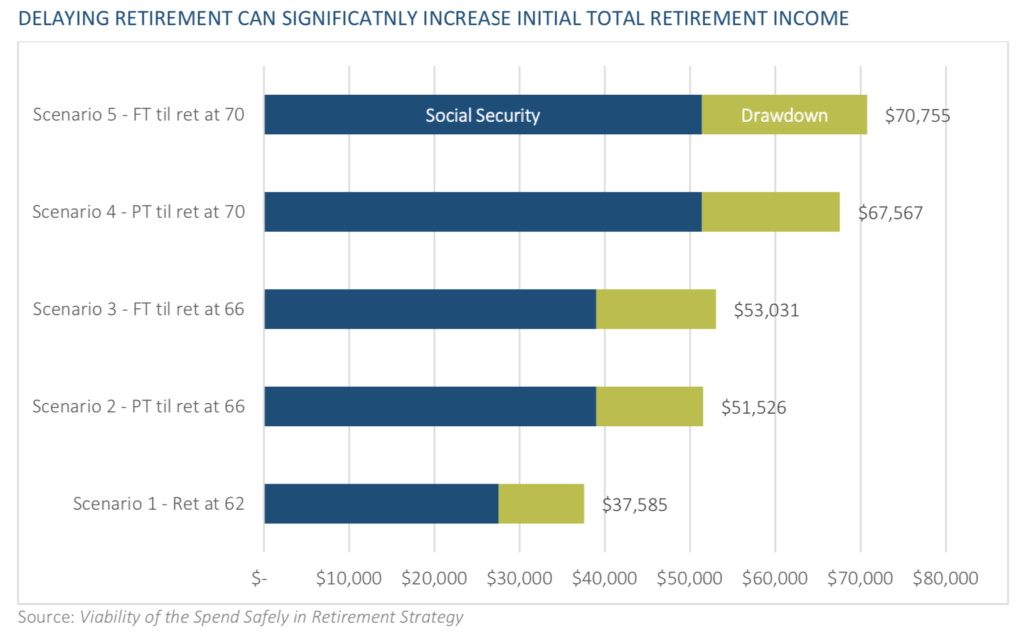

Figure 1 below shows a graph from the Viability of the Spend Safely in Retirement Strategy report that projects total retirement income in the initial year of retirement at various retirement ages for a hypothetical 62-year-old married couple. Their household earnings are $100,000 per year, and they have $350,000 in retirement savings. This assumed savings amount is higher than the average and median savings levels accumulated by current older workers.

The analysis considers five scenarios:

- Both members of the couple retire completely at age 62, and both immediately begin Social Security benefits and drawing down retirement savings.

- Both keep working part time until their Social Security Full Retirement Age (66 and 6 months for this couple), then both start Social Security and drawing down their retirement savings. “Working part time” is defined here as earning enough to pay for their current living expenses but not continuing to contribute to their retirement savings.

- Both continue working full time until their Social Security Full Retirement Age, then both start Social Security and drawing down their retirement savings. In this scenario, the hypothetical couple continues to contribute 10% of their pay to retirement savings.

- Both keep working part time until age 70, then both start Social Security benefits and drawing down retirement savings.

- Both continue working full time until age 70, then both start Social Security benefits and drawing down retirement savings.

Note that this couple’s projected total annual retirement income almost doubles when they delay retirement, from $37,585 when retiring at age 62 to $70,755 when retiring at age 70. Although this specific example was for a married couple with assumed levels of earnings and savings, this example illustrates concepts that most likely will apply to many situations, including that of single retirees.

Note also that the amounts above represent the retirement income this couple can expect in the initial year of retirement. In future years, their Social Security income will increase due to cost-of-living adjustments, whereas the income from savings drawdown will depend on future investment earnings. In other words, the blue bars represent the portion of total retirement income that’s risk-protected, and the red bars represent the portion that’s subject to investment, inflation, and longevity risks.

For the example in Figure 1, the annual amount of retirement income generated by savings was calculated by assuming the retired couple would withdraw amounts equal to the IRS required minimum distribution (RMD) rates. The same methodology was used to calculate their retirement income before the age the actual RMD rules are required (currently age 70, changing to age 72 in 2021). There are also other viable methods of generating retirement income; these will produce different amounts of retirement income in the initial year of retirement and throughout retirement.

With Scenario 2 in Figure 1, both members of the couple deploy a downshifting strategy, working just enough from age 62 to age 66-1/2 to cover their current living expenses, which allows both Social Security and savings to grow.

Under Scenario 3, both members of the couple continue working full time and contributing to savings. Note that there isn’t a significant difference in the eventual retirement income between these two scenarios: $51,526 vs. $53,031. This result illustrates that most of the advantage of continuing to work results from the delay of starting Social Security and taking withdrawals from savings. Continuing to contribute to savings, while definitely helpful, adds relatively less to the eventual retirement income. Scenario 4 compares downshifting from age 62 to 70 with Scenario 5, working full time until age 70, with similar results.

These analyses show the potential advantage of a downshifting strategy for older workers who don’t want to or can’t continue working full time, but who haven’t saved enough for complete retirement.

Decision #2: When to Start Social Security Benefits

Social Security benefits provide the most risk protection of all sources of retirement income, protecting against longevity risk, inflation risk, investment risk, and cognitive risk. When a middle-income worker optimizes their Social Security benefits through a careful delay strategy, typically a very large percentage—often two-thirds, three-quarters, or more—of their total retirement income is risk-protected. Comparing the relative sizes of the blue and red bars in Figure 1 illustrates these outcomes.

As a result, it makes sense to maximize this valuable source of retirement income. To help with this goal, pre-retirees can use one of several online programs that help analyze the optimal age at which to start Social Security benefits.

Decision #3: How to Deploy Retirement Savings to Generate Retirement Income

The baseline Spend Safely Strategy uses the IRS required minimum distribution rates to calculate the annual income that’s generated from retirement savings. This strategy has a number of straightforward refinements and adjustments that can customize the baseline strategy to reflect specific goals and circumstances that retirees might have.

For example, retirees might choose to use a Social Security bridge strategy to increase the amount of their retirement income, as well as the portion of their total retirement income that Social Security will deliver and is risk protected. A Social Security bridge strategy uses retirement savings as a temporary substitute for the estimated income a retiree will ultimately receive from Social Security until they actually start their Social Security benefits. It can enable a worker to retire before the optimal age at which to start Social Security benefits.

Let’s see how a Social Security bridge strategy could increase the total retirement income in Scenario 3, where the couple works full-time until age 66-1/2. In this example, the husband of the couple would use a bridge strategy to delay Social Security until age 70. In this case, the total annual retirement income would increase from $53,031 to $57,637, without changing the retirement date.

Another refinement addresses retirees who might feel more comfortable with additional guaranteed, lifetime retirement income to supplement their Social Security income. In this case, they can use a portion of their savings to purchase a cost-effective single premium immediate annuity (SPIA) through an annuity bidding service.

To continue the current example for Scenario 3, if the married couple adopted a Social Security bridge strategy and, with remaining funds, purchased a SPIA with a 100% joint and survivor annuity, their total annual retirement income would further increase from $57,637 to $63,892 (using annuity purchase rates from ImmediateAnnuities.com in mid-June 2020). This amount is more than $10,000 higher than the base retirement income amount for Scenario 3.

While these two refinements have significantly increased total retirement income, they also reduce the amount of wealth that retirees can access if their circumstances change. Pre-retirees should consider this result carefully when deciding how much savings to devote to a Social Security bridge payment or to purchasing an annuity.

Other retirees may want to invest substantially in stocks for the potential to grow their retirement income. Since a large portion of their retirement income is already risk protected by Social Security, they might feel comfortable assuming some calculated investment risk. The SCL/SOA research report, Viability of the Spend Safely in Retirement Strategy, contains historical analyses that illustrate this basic retirement investing dilemma: Most of the time, but not always, retirees can potentially increase their retirement income by investing in stocks.

Decision #4: Which Living Expenses Can Be Reduced to Fit Decreased Income in Retirement

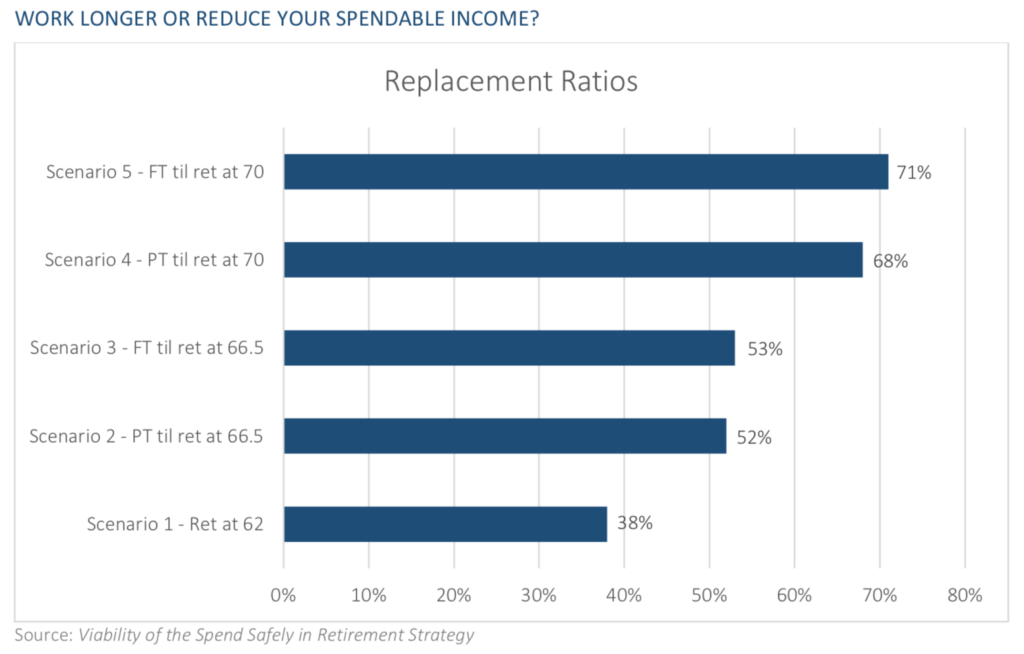

Conventional retirement planning wisdom advocates that retirees need a retirement income that replaces 70% to 80% of their pre-retirement income to continue their standard of living in retirement. Yet most older workers haven’t accumulated sufficient savings to achieve this goal.

Figure 2 shows that the hypothetical couple described earlier won’t approach these goals unless they both work until age 70.

Remember that this hypothetical couple has more retirement savings than most American workers their age. As a result, most older workers face a tough choice: work longer than they planned, reduce their standard of living, or do some combination of the two. To help matters, they can also explore alternative methods to generate retirement income from their savings, as illustrated by the previous example.

If a retiree needs to reduce living costs, housing often represents the largest target for most people. By relocating, retirees might also achieve other goals, such as moving to a home or neighborhood that will be more supportive in their later years.

Decision #5: Whether to Deploy Home Equity

Most retirees have more wealth in their homes compared to their retirement savings. If retirees’ Social Security benefits and income generated by savings aren’t sufficient to pay for their living expenses in retirement, they may need to explore ways to deploy their home equity. One straightforward method is to sell their home, realize a capital gain, downsize to a less expensive home, and then deploy the net proceeds to generate retirement income.

Another possibility is to use home equity to purchase a reverse mortgage. The SCL/SOA report, Optimizing Retirement Income by Integrating Retirement Plans, IRAs, and Home Equity, analyzes and compares three different methods to use a reverse mortgage to enhance retirement security. Any solution to deploy home equity is highly dependent on a retiree’s financial circumstances, preferences for housing, and willingness to incur the costs of a reverse mortgage.

Pre-retirees and retirees need help

The analyses and insights presented in this article can help older workers make the five important retirement income decisions noted earlier. There are several other important decisions that don’t involve retirement income; they’re beyond the scope of this essay.

Ideally, pre-retirees would address these decisions as they transition into retirement. However, the decisions have high stakes for retirees’ financial security for the rest of their potentially long lives. And these issues are complex, making many of the decisions presented here beyond the skills of most pre-retirees and retirees. They’re going to need help.

Employers can help their older plan participants by offering retirement income options in their defined contribution plans, delivering communication materials about retirement income strategies, and offering part-time positions to older workers to enable them to downshift and delay starting Social Security benefits and drawing down retirement savings. Parts Two, Three, and Four in this series explore these ideas further.

Financial institutions and advisers can incorporate these analyses and insights into their products and services as well. Building financial security for long retirements is a serious challenge, and we all have roles that we can play to help.

Steve Vernon, FSA, is a Research Scholar, Stanford Center on Longevity, and co-author of the SOA-sponsored research report “Viability of the Spend Safely in Retirement Strategy,” which forms the foundation for the ideas in this series of essays. Vernon is also the author of a consumer-facing book based on this research: “Don’t Go Broke in Retirement: A Simple Plan to Build Lifetime Retirement Income.” He can be reached at [email protected].