Life is so frantic today—thanks to devices and software that help us compress more activity into tinier increments of time—that people are too busy to look for investment advice from sources other than friends, family, or familiar brands like Fidelity, Charles Schwab and Vanguard.

So says the latest edition of The Cerulli Edge—Retail Investors Edition, from Boston-based Cerulli Associates, the global consultants.

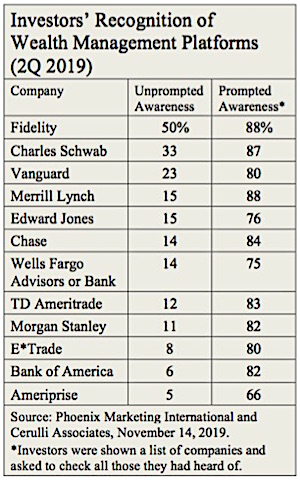

“Widely reported investor satisfaction with their current financial providers, combined with demanding and distracted lifestyles, leave well-known wealth managers in a position of strength,” the report said. “Unaided awareness is one of the most crucial metrics in understanding a firm’s significance in the lives of potential consumers.”

In short, brand strength is king. As a retail consultant once said to me, “What makes a great brand? It’s a promise kept over and over and over.” As a Vanguard institutional executive once told me, “I tell new hires, ‘Just don’t screw it up.’” He meant nothing more complicated than “Don’t mess with success.”

Vanguard, Schwab and Fidelity have been building their brands since the 1970s, after the stock market bottomed out in the recession of 1974. While others were moaning about the death of stocks, their leaders recognized (along with Warren Buffett) that the only direction for the market was up.

Each grabbed a niche—Vanguard in low-cost indexing, Schwab in discount brokerage, and Fidelity in retirement plans and actively managed mutual funds—and never let go. Each steadily reaped the Zeitgeist of demographics (40 years of Boomer savings), financial deregulation, massive money creation (thanks to federal deficit spending), the resulting asset value inflation, and the federally-subsidized (via tax deferral) 401(k) system, which brought “Main Street to Wall Street.”

Each of their highly visible leaders—Vanguard founder Jack Bogle, Fidelity fund manager Peter Lynch, and Charles Schwab himself—gave their firms trustworthy public faces. Until recently, one of their few brand-strength peers from the 1970s was PIMCO, whose voluble co-founder, Bill Gross, rode the bull market in total bond returns—created by the long descent from Fed chairman Paul Volcker’s double-digit interest rates—until falling yields could no longer support the fees associated with his actively managed bond funds.

Scott Smith, director of advice relationships at Cerulli, explained why these three firms have proven to be the fittest survivors in the financial service game.

“Fidelity achieves an unmatched level of unaided awareness among affluent investor respondents, with an average of 50% citing the firm when asked to name a provider in the space,” he writes in The Cerulli Edge.

“The firm’s extensive advertising, combined with its presence as a retirement plan provider for millions of participants, make it the most formidable brand in the wealth management segment,” Smith wrote.

“The firm’s extensive advertising, combined with its presence as a retirement plan provider for millions of participants, make it the most formidable brand in the wealth management segment,” Smith wrote.

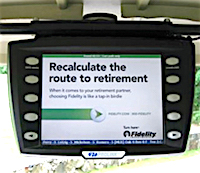

In early 2009, as the financial crisis bottomed, then-Fidelity chief marketing officer Jim Speros, his internal ad team, and the Boston ad firm Arnold Worldwide conceived of an animated green navigation line, like those found in GPS systems, that would lead investors back to success. Fidelity still uses the award-winning concept. According to MediaRadar.com, Fidelity spent over $100 million in 2018 on print, digital and television advertising.

“Though frequently not the first to enter developing segments, once [Fidelity] has decided to do so, the move is usually decisive, which bodes well for the firm’s ability to maintain its premier position among investors, advisors, and retirement plan sponsors,” Smith wrote.

Charles Schwab is the name that 33% of affluent investors surveyed mention when asked to name a provider in the investment space, according to Cerulli. In ad-speak, that’s called a “strong unaided awareness level” within the target market.

“Schwab makes a concerted effort to increase awareness levels through a variety of ongoing ad campaigns, highlighting the firm’s strengths,” Smith wrote. “The firm often takes a leading position in advancing investor-focused initiatives.”

The “Talk to Chuck” ad campaign that began in 2005 featured its CEO and helped humanize the company. “It’s a bit of a risky move,” Marc E. Babej, a brand and corporate strategy consultant, told a New York Times advertising columnist at the time about the campaign. “‘Talk to Chuck’ sounds like, ‘We love you, man.’

“But it stands to get attention,” and “if Chuck becomes an icon for the company, in a ‘What would Chuck do?’ way, it would help set Schwab apart in the marketplace.” It did, and it continues to.

By contrast, Vanguard has done relatively little advertising or marketing. Bogle, who died last January, was philosophically averse to spending current customers’ money to court new customers. Yet 23% of investors surveyed cited Vanguard when asked to name a company in the investment space. (I worked at Vanguard from 1997 to 2006.)

“By opting out of the more active marketing options used by Fidelity and Schwab, Vanguard consigns itself to a somewhat reduced awareness level, but this has little downside for them,” according to Smith. “The firm has been an early leader in the low-cost investing movement. Even though other providers have made efforts to match, or beat, Vanguard’s initiatives, the firm maintains an unmatched public perception as a low-cost provider.”

“Costs matter,” Bogle was famous for saying. He tried not to let investors forget that even a modest-seeming 1% annual expense ratio can reduce lifetime savings by 25% or more. According to one of his biographers, Bogle was not born a discounter. Instead, after the 1974 crash, he decided that coaxing traumatized investors back into mutual funds would require ultra-low prices as well as optimism about the future of the economy.

Jack Bogle

In the decades that followed, he was pre-disposed to pass the savings from rising economies of scale back to his customers. He had the liberty to do so. Vanguard was not simply a private company, with no army of common stock shareholders or Wall Street analysts to please, but a marketing-and-back-office cooperative owned by its member mutual funds, which are in turn owned, technically, by their shareholders. (Indeed, Vanguard’s internal transfer-pricing arrangement, which provided services to the funds “at-cost,” would lead in 2014 to accusations of tax evasion by a former employee. No regulatory agency bothered to prosecute.)

Though a formidable competitor not inclined to doubt his own instincts, Bogle was quite modest about Vanguard’s achievements. He gave much of the credit for the company’s success to the 401(k) system, the information technology revolution, and the Boomer retirement wa ve.

ve.

Bogle did not own Vanguard. No one does. Even insiders are hard-pressed to articulate its precise ownership structure. As an observer once said, “Vanguard just seems to float out there in non-Euclidean space, like the Eye of Providence floating above the pyramid on the back of a dollar bill.”

© 2019 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.