If you’ve taken the famous Myers-Briggs personality inventory test, you may remember that it measured whether you were relatively extroverted or introverted, sensory or intuitive, thinking or feeling, and judging or perceiving—traits identified a century ago by psychoanalyst Carl Jung.

Wade Pfau, who heads the doctoral program in retirement income at The American College of Financial Services, takes a similarly scientific approach to his field. He and colleague Alex Murguia have developed questionnaires to help advisers to understand the personalities of older clients.

These questionnaires, in theory, can reveal clients’ attitudes toward the value of financial advice itself, and their tolerance for risk in retirement. The results, Pfau believes, can help advisers deliver the appropriate kind of advice in the appropriate way to each client.

Alex Murguia, Ph.D.

Pfau describes this approach in rigorous detail in two academic papers that he and colleague Murguia published earlier this year. Murguia is a Ph.D. and CEO at RetirementResearcher.com, the web platform that Pfau established for blogging and entrepreneurial ventures.

This work is grounded in their beliefs—which RIJ shares but which may not be universal—that income planning differs significantly from accumulation-stage planning, that no two retirees are alike, and that retirees’ preferences, not advisers’ preferences, should determine their income-generation strategy.

Tailoring a client-specific strategy

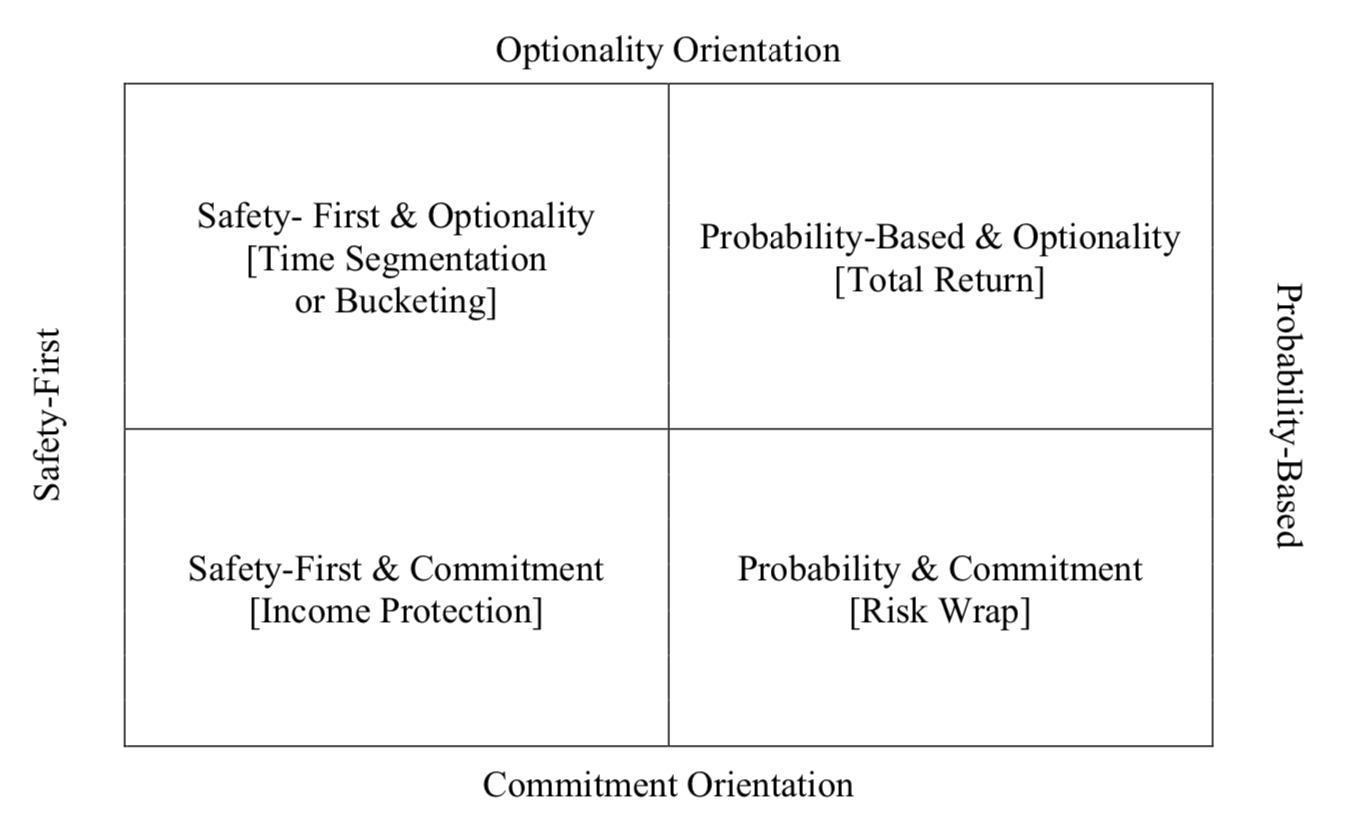

In the paper titled, “A Model Approach to Selecting a Personalized Retirement Income Strategy,” Pfau and Murguia describe a four-quadrant chart that they call the “Retirement Income Style Awareness Matrix.” It’s a kind of Morningstar style-box for matching clients with income strategies.

Within this framework, the authors assume that retirees have four basic financial concerns, whose weight varies by client: Longevity (outliving savings), Lifestyle (maintaining a desired standard of living), Liquidity (having cash for emergencies), and Legacy (leaving a bequest).

The next step in developing an accurate style box is to determine the client’s Retirement Income Style, using a proprietary questionnaire. The clients’ answers reveal their mindsets on six different (and somewhat self-explanatory) scales:

- Probability-Based vs. Safety First

- Optionality vs. Commitment

- Time-Based vs. Perpetuity Income Floors

- Accumulation vs. Distribution

- Front-Loading vs. Back-Loading

- True vs. Technical Liquidity

Since a few of these 12 factors are closely correlated, Pfau and Murguia reduce the list to four preferred orientations (Safety First, Optionality, Commitment, and Probability-Based) leading to four styles: Safety-First & Optionality, Probability-Based & Optionality, Safety First & Commitment, and Probability-Based & Commitment,

Finally, the authors map these four styles to four income strategies (boiled down from 36 valid strategies that Pfau identified in past research): Systematic withdrawals from a total return portfolio; time-segmentation (bucketing); partial annuitization; or “risk wrap” (the use of deferred annuities with lifetime income benefit riders).

Here’s what the Retirement Income Style Awareness Matrix looks like:

Choosing the right pitch

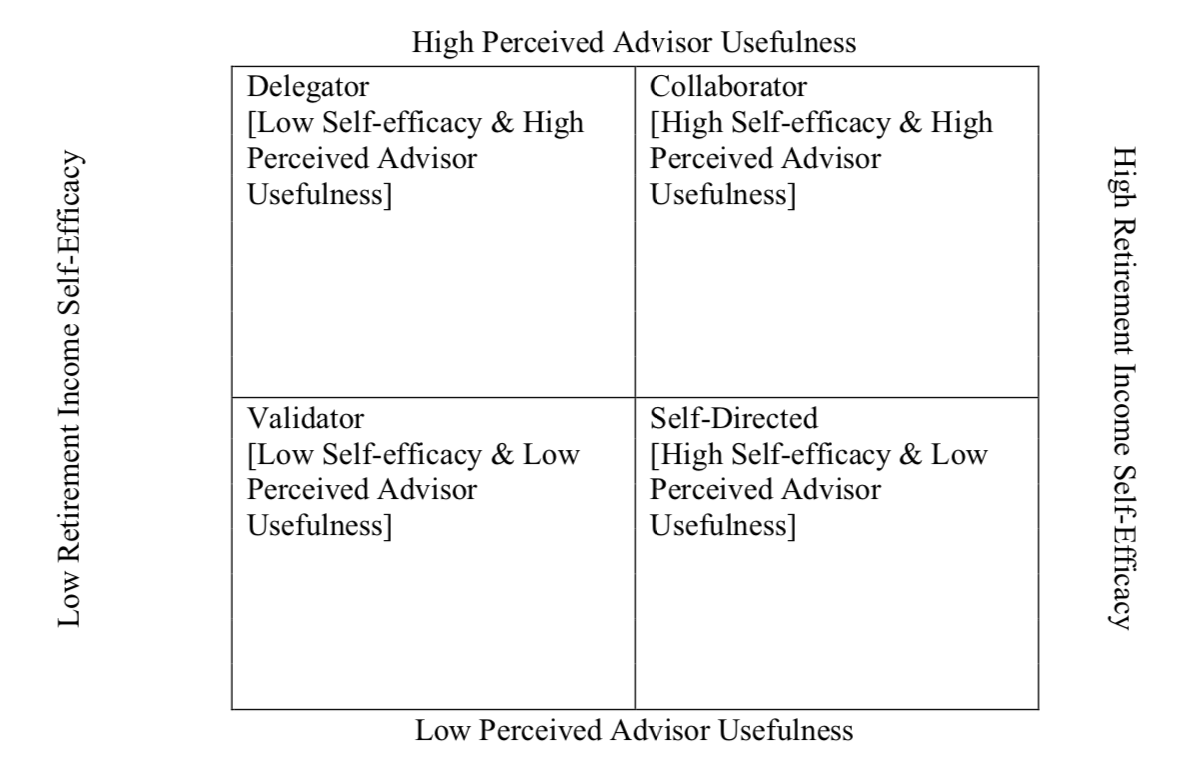

Pfau and Murguia apply a similar method to the creation of a “Financial Implementation Matrix,” which they describe in a paper titled, “Retirement Income Beliefs and Financial Advice Seeking Behaviors.” This matrix assigns clients to one of four groups based on their answers to questions designed to elicit their attitudes toward financial advisers and the value of advice.

A questionnaire leads to scores on six characteristics:

- Self-efficacy (the ability to complete tasks)

- Financial biases (susceptibility to classic behavioral traps)

- Numeracy (financial literacy)

- Numeracy Self-Awareness (perception of financial competence)

- Inertia (the opposite of self-efficacy)

Based on his or her score, each client can be categorized as a Delegator, Collaborator, Validator, or Self-Directed. Delegators and Collaborators both see advisers as useful, but Collaborators score higher on Self-Efficacy. Validators and Self-Directed are skeptical of the value of working with an adviser, but the Self-Directed have higher Self-Efficacy.

Here’s what the Financial Implementation Matrix looks like:

The better advisers understand the client, the better they can fine-tune their approach. “A delegator and a collaborator need a different cadence with their advisor for the relationship to be productive. In addition, a validator and self-directed investor may need different options that do not require an ongoing professional relationship,” the authors wrote.

Wade Pfau

This fine-tuning leads to more effective advice, and more success for everyone involved. “For a financial professional, the ability to present advice in a manner that resonates with an individual is paramount to a successful relationship. More importantly, it will help them follow through with their retirement income plan,” the paper said.

Not for everybody

These two papers, and the trademarked intellectual property (RISA and FI) they describe, are not ready-to-implement tools. Rather they are descriptions of the research that Pfau and Murguia used to validate that property, which they have already begun to turn into a business and to market to advisers through webinars. “We are in the process of creating a business for this. We are doing a build-out for it now,” Pfau told RIJ in an email this week.

In addition to drawing on the relevant academic literature, their original research consisted of the surveying some 1,500 subjects, drawn largely from the subscribers to Pfau’s blog at RetirementResearcher.com. More than half of these subjects ranged from 59 to 70 years old and half had investable assets of between $1 million and $3 million. The results of those surveys enabled them to build the matrices or style charts.

Pfau and Murguia’s approach will probably appeal most to independent advisers who are what RIJ has called “ambidextrous.” That is, advisers who know how to lever the complementary benefits of investments and annuities, and who aren’t confined by their business models to a certain set of retirement income strategies.

Advisers won’t be surprised to hear that effective advice demands listening to clients as much as leading them. “Forcing the ‘wrong’ strategy on someone is not appropriate,” the authors write. “There are dangers to initially filtering strategies based on a financial professional or an investment media pundit’s world view rather than seeking to better understand what strategies resonate with an individual’s retirement income style.”

© 2021 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.