Yesterday’s second quarter earnings conference call with senior executives of Athene Holding offered a window into the most significant trend in the life insurance industry over the past five years: the development of an asset management model that feeds on blocks of fixed annuity contracts.

Athene, financed by the private-equity (PE) firm Apollo Operating Group (Apollo), helped pioneer a trend that started after the Great Financial Crisis. The trend has been tantamount to turning what we knew as the “life insurance” industry into something new: the “liability origination platform” business, as a recent study by Conning described it.

In short, private equity firms are buying (mostly) fixed annuity assets from large life insurers and, by using offshore captive reinsurers, freeing up capital that they can redeploy into riskier, higher-yielding assets like collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) and commercial real estate-backed securities assets (CMBS).

The trend was trailblazed by Athene, which was created in 2013 when Apollo bought Aviva Life (assets of $56 billion) and renamed it. In 2016, Athene went public in a $1.08 billion IPO. In 2018 it added annuity assets from Voya and Lincoln Financial. This year it acquired, via a reinsurance deal, $26 billion worth of Jackson National Life fixed-rate and fixed index annuities (FIAs).

“Major life insurance groups continue to reduce their exposure to legacy in-force business and to release trapped capital and resources,” said the chairman of Resolution Re last December, when he announced his firm’s still-pending acquisition-and-reinsurance deal with Voya Financial, including the transfer of assets worth an estimated $20 billion.

The price of Athene’s stock, like the share prices of other life insurers, has not recovered as well as the overall market from the COVID19-related equity crash in March. But on yesterday’s earnings call, the Athene executives were ebullient. Athene has grown rapidly, and the executives see the potential to sell a lot more FIAs to baby boomers and the opportunity to buy many more underperforming blocks of fixed annuity business.

How much business is out there? Almost a trillion dollars’ worth. According to Todd Giesing, director of annuity research at LIMRA’s Secure Retirement Institute, in-force fixed-rate annuities have a current value of $450 million. In-force fixed indexed annuities have a current value of $505 billion. (Variable annuity assets have a current market value of $1.94 trillion, but those assets are in separate accounts and contract owners can liquidate them with relative ease; fixed annuity assets are in the insurer’s general account and are less subject to withdrawal.)

Long-dated liabilities in demand

Since 2014, according to a report this year by the consulting firm Conning, over two dozen “liability origination” or “liability consolidation” companies have been formed in the U.S. or abroad to create, acquire or reinsure blocks of fixed annuity business and “redeploy” the capital more profitably.

“We’ve been following these companies—Athene, Global Atlantic, FGL—since 2013 or 2014. We’re also following the newer companies with the same business model. Since 2015, about 30 new companies with this model have come into being. We refer to it as a liability platform,” Conning’s insurance research director Scott Hawkins told RIJ recently. [Note: The private equity firm KKR is in the process of buying Global Atlantic.]

“They’re looking to accumulate annuity or pension liabilities, because they are a form of permanent capital. That’s desirable for those owners; the money will stay with them for a long period, they can invest in asset classes without an investor suddenly deciding to redeem. They can enjoy a longer time horizon, because the liabilities are longer.” In the case of FIAs, investors may not withdraw their money for as long as 10 years.

“Yes, there has been ‘some’ reconfiguration in the industry over the past six to eight years, with private equity/asset management groups acquiring annuity insurers,” said David Paul of ALIRT, which tracks life insurance companies, in an interview. “Athene/Apollo would likely be ‘Exhibit A,’ but they aren’t the only one. To speak of it as ‘a’ reconfiguration of the life industry overstates their influence.

“These asset managers feel that they have an investment edge, in part through the acquisition of private debt or CLOs, and they believe can make better spreads than traditional insurance investment shops, thereby offering more attractive rates and/or achieving better profitability. Some have also leveraged offshore reinsurance operations for tax and capital arbitrage.”

Pros and cons of PE-led insurance

What does it mean for the investors—the baby boomers who rely on annuities for safe accumulation or guaranteed retirement income? That’s a complicated question with no definitive answer, at least not yet.

On the plus side, life insurance companies have received fresh infusions of cash. The private equity (PE) firms talk about the tens of billions of capital they have poured into “primary” life insurance companies—relieving them of books of business that they couldn’t profitably support. Indeed, in today’s earnings call, Athene CEO James Belardi called Athene a “solution provider” for other firms.

The private equity companies also talk about their ability to pass on their greater efficiency and profitability to the older Americans who own FIAs. In response to a question from one stock analyst today, Belardi said Athene’s FIAs offer participation rates that are about “10 basis points higher” than the competition.

He also attributed Athene’s 40% increase in sales in the first half of 2020—at a time when the rest of the annuity industry slumped—to Athene’s use of “bespoke indexes.” These are custom or hybrid indices created by investment banks. The vast majority of FIA assets industry-wide is in the S&P 500 Index, but only “about half of our in-force business is in the S&P 500,” Belardi said. Athene has also had success in 2020, he said, “because our competitors have pulled back.”

The PE-led firms are also providing solutions to large corporations that want to sell their defined benefit pension plans—and all the longevity risk that attaches to them–to a life insurance company, which will convert the group annuity to individual annuities. “Pension risk transfers,” a business in which Prudential Global Investment Management (PGIM) has been the leader, is another way that life insurers can obtain large blocks of money. Like FIA assets, those assets are withdrawn by retirees at a slow or predictable pace, making them ideal for funding riskier investments. The life insurer thus provides a solution to corporations by relieving them of hard-to-quantify longevity risk; the corporations don’t know how long their pensioners will live.

CLOs encounters

But some observers are wary of the wave of acquisitions of life insurers by private equity firms, and have worried about this trend since it started a decade ago. The retired Indiana University insurance professor Joseph M. Belth, for instance, warned about the risk that policyholders might suffer service lapses under the issuers’ new owners, who may have chosen not to sell new annuities or life insurance policies at all.

“Problems are to be expected when private equity firms create or acquire long-term obligations of insurance companies in an effort to earn short-term profits for the benefit of their investors,” Belth wrote on his blog two years ago, after Athene agreed to pay a $15 million fine for neglecting important services to policyholders.

Others are concerned about the safety of the assets that the PE-led firms are investing in, such as CLOs. These are the securitized bundles of loans to corporations with below investment-grade credit ratings. (The National Association of Insurance Commissioners issued a report on CLOs recently.)

After the Great Financial Crisis, banks greatly reduced that type of lending. Life insurers and their affiliate asset managers stepped in to satisfy the demand for credit from corporations already burdened by debt. Like other securitized investments, CLOs are divided into tranches. The uppermost tranche is held out to be as safe as a Treasury bond; the bottom tranche is as risky as a stock.

Life insurers typically buy the highest or second highest tranches, where they can earn higher yields than on similarly low-risk assets. CLOs comprise about 9% of Athene’s investments, Belardi said, adding that the “diversified pools of senior secured loans generated returns about 100 basis points (one percentage point) higher than comparably risky corporate bonds.

“While CLOs have volatility,” he said, “we will hold them to maturity. There’s been no principal impairment in CLOs. There have been downgrades but no defaults.” Regarding the economy, he said, “We’re not out of the woods yet.” He sees potential weakness in loans to airlines and fleet leasing companies, and strength in real estate. “We’ll be a player in commercial real estate-backed and residential real estate backed securities. We expect people to stay in their homes” despite high unemployment.

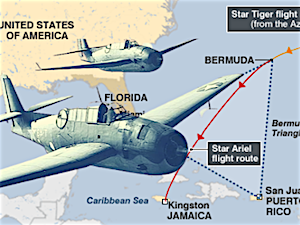

The Bermuda triangle

The use of captive (i.e., owned by the same parent as the life insurer) offshore reinsurers, many of them based in Bermuda, also troubles some observers. Bermuda uses a different accounting standard (GAAP), which doesn’t require reinsurers to hold as much reserve capital as U.S. (statutory) accounting rules do. A U.S. life insurer can create its own reinsurance company in Bermuda and then can move a block of annuity business (“reinsure” it) to that new company. This act alone frees up capital, which the life insurer can use for other purposes.

“By having a Bermuda-based reinsurer, some companies are doing indirectly what they couldn’t do if the assets and liabilities stayed with the original domestic issuer: Get a credit for having reinsurance and take hard assets out,” said Larry Rybka, CEO of Valmark Financial Group, which helps advisors monitor the products they sell.

As blocks of annuity assets and liabilities accumulate (for accounting purposes) in Bermuda, the liabilities might not be sufficiently capitalized, Rybka said. He thinks there’s a danger that, behind a complex screen of transactions between closely affiliated companies—the life insurer, asset manager, and reinsurer are frequently all part of the same publicly held or private equity company—life insurers might have an incentive to capture profits for their shareholders at the expense of their policyholders.

Rybka points to a warning expressed by Federal Reserve researchers Nathan Foley-Fisher, Nathan Heinrich and Stephane Verani in a February 2020 paper: “A widespread default or downgrade of risky corporate debt could force life insurers to assume balance sheet losses of their CLO-issuing affiliates, wiping out their equity. In a worst-case scenario, the perception of balance sheet weakness could incite liquidity-sensitive institutional investors to withdraw from those life insurers.”

Not everyone agrees with all the specifics of Rybka’s view, which reflects the complexities involved. The motive for using offshore reinsurers “seems largely to be tax relief, and not regulatory arbitrage,” said Dan Hausmann, one of ALIRT’s founders. “There may be some differences in investment requirements, but any material transaction a company does would require approval from the states they do business in then. People can’t just say, ‘Let’s move $5 billion to Bermuda.’ Domestic insurers in most cases keep legal control of policy liabilities and the assets in support of those liabilities.”

So what implication does this trend—now a decade old and evidently accelerating—have for the “retirement income” industry and its stakeholders? We’ll address that broad question in future articles. But there’s no question that we’re seeing the further evolution of life insurers into asset managers.

“The larger life insurers are gradually becoming more and more asset management focused, rather than protection focused. Some will stay on life insurance, but you hear more and more of them say, ‘We’re about managing assets,’” Conning’s Hawkins said. “The large players are becoming asset managers. That’s a trend that I’ve certainly seen over my 35 years in the business.”

© 2020 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.