Why ‘Offshoring’ Annuity Risk Is Wrong

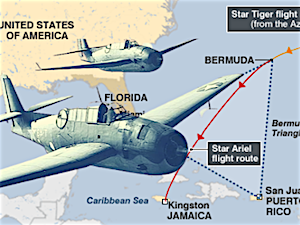

Many for-profit US life/annuity companies do not use independent reinsurers. They use an affiliated or captive reinsurer in a jurisdiction like Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Vermont, or Arizona. This makes their operations less transparent.