The recognition that a killer flu virus was spreading quickly and silently through the U.S. population sent investors running for safety last March, igniting a financial panic and a recession that required extraordinary fiscal and monetary responses from the U.S. Congress and Federal Reserve.

By lowering the overnight lending rate to zero, and by buying corporate bonds for the first time ever, the Fed braced the falling prices of existing fixed income securities. Congress dropped trillions in “helicopter money” on businesses and individuals. Panic subsided. Stock and bond prices rose.

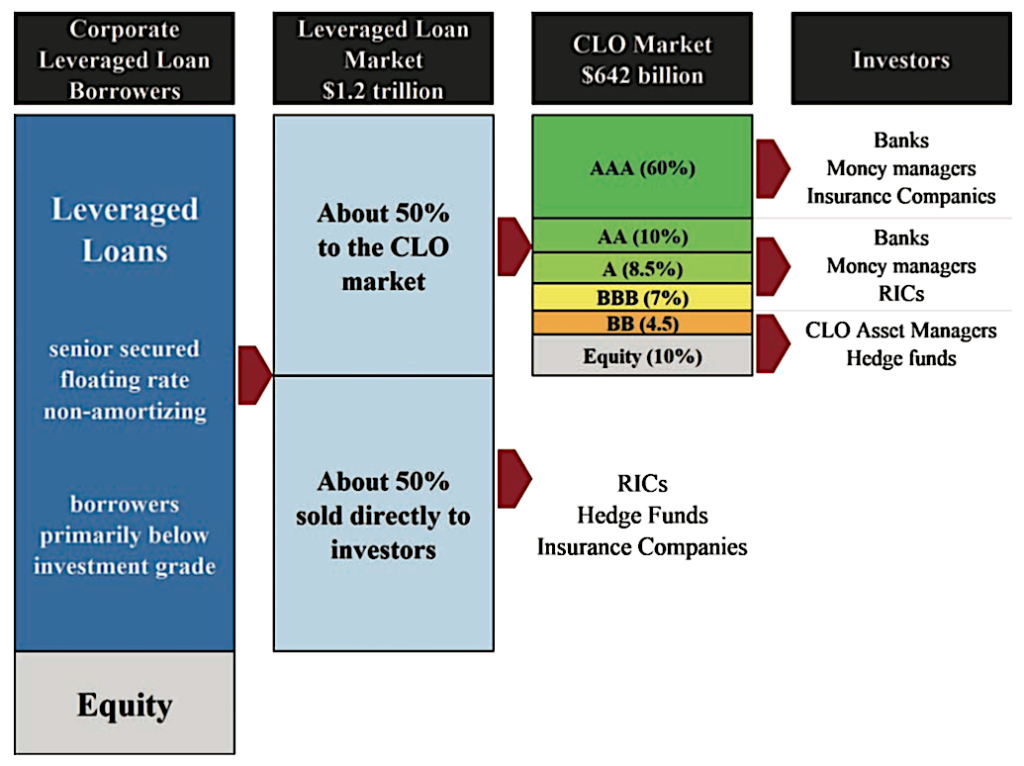

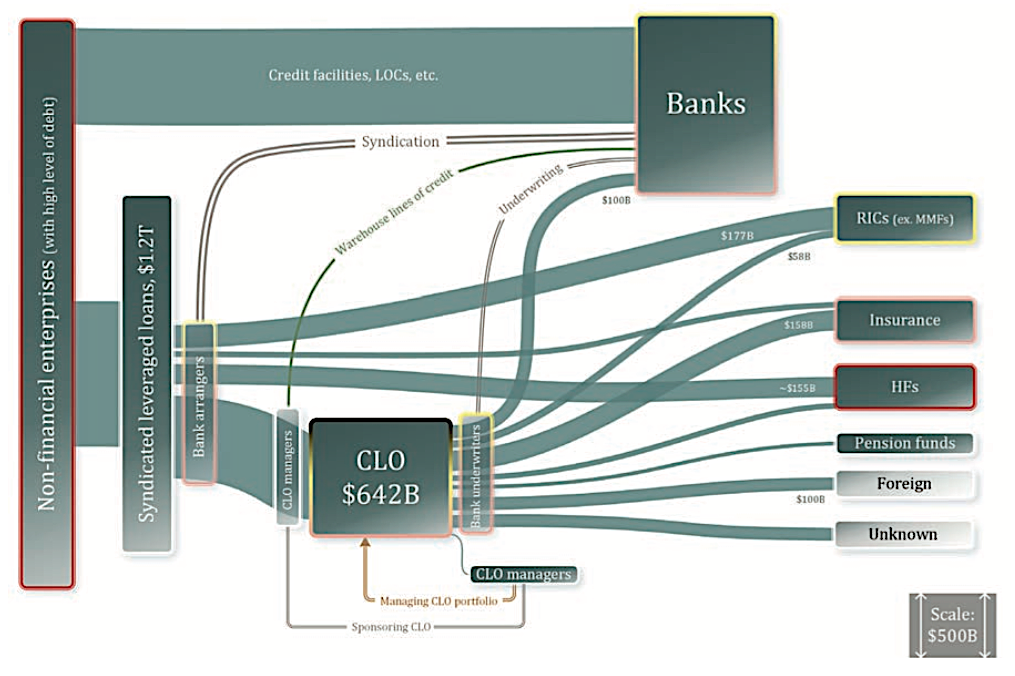

Amid the market crash and recovery, people who follow life insurers watched how the value of CLOs, or “collateralized loa obligations,” held up. Life insurers now own about $150 billion in investment-grade “senior tranches” of these securitized bundles of below-investment-grade “leveraged loans” to small and mid-sized companies.

Those senior tranches survived last spring’s crisis, despite a few high-profile bankruptcies among companies with leveraged loans (Neiman Marcus, J. Crew, J.C. Penney, Hertz). But their inherent risks have not gone away. The story of what happened to those loans last spring—and to America’s entire $54 trillion credit (i.e., debt) market—is told in absorbing detail by a new report, “U.S. Credit Markets: Interconnectedness and the Effects of COVID-19 Economic Shock,” from the Division of the Economic and Risk Analysis of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Six major segments that encompass $44 trillion of the overall U.S. credit market: short-term funding, corporate loans, leveraged loans and CLOs, municipal bonds, residential mortgages, and commercial mortgages, are covered in the SEC’s 88-page report, released Monday. Here we’ll focus on the section devoted to CLOs, because of their relevance to the current state of the life insurance industry.

CLOs are providing some of the extra juice—investment income—that’s fueling the strength of a group of relatively new life insurers that specialize in creating and managing fixed annuity liabilities. Like other securitizations, CLOs hold out the promise that their senior tranches—owners of which are the first to get paid, and have access to collateral—offer the same safety as AAA or AA corporate bonds while delivering significantly higher returns.

These new or re-organized life insurers—including Athene, Global Atlantic, Fidelity & Guaranty Life, Delaware Life, Security Benefit and now American Equity—have ties to global asset managers accustomed to dealing in asset-backed securities like CLOs, private equity, leveraged loans and other complex, illiquid instruments. Investment departments of traditional life insurers rarely have the resources to play in that space.

All of these private equity-linked life insurers have been amassing fixed indexed annuity liabilities (i.e., money that will be paid back to mom-and-pop investors after three to 10 years) by buying big blocks of in-force annuities or selling new contracts.

That money becomes raw material for the purchase of complex investments. With superior economics—higher investment returns, capital arbitrage through offshore reinsurers, lower overhead—these new or refreshed life insurers can offer superior crediting rates on the long-dated fixed indexed annuities that are sold to older investors and retirees.

The annuity industry has, as a result, undergone an historic change in the past five to 10 years. It may even have been saved. Without the arrival of deep-pocketed private equity companies, low interest rates may have forced traditional insurance companies to take extraordinary measures to keep the promises they made to annuity contract owners back when interest rates were higher.

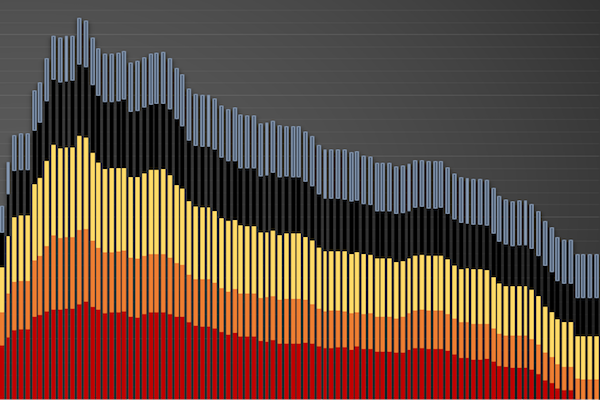

The new SEC report describes the CLO market as more than doubling to $642 billion today from $250 billion in 2012. The largest holders of CLOs are insurance companies, with about 25% of outstanding CLOs, followed by banks and investment companies, which together hold about 25%.

“The fundamental risk in the leveraged loan and CLO markets is the financial health of leveraged borrowers, i.e., their credit risk,” the report noted. The share of loans rated B2 or lower (B or lower on the S&P scale) rose to 60% at the end of 2019 from 40% in 2016.

For the types of senior CLO tranches that insurance companies hold—and which account for small percentages of a life insurer’s assets—the risk is deemed to be low. But “the prospect of a deterioration in the risk profile of AAA CLO tranches is worthy of examination primarily because it could cause a large class of investors (e.g., investors who must hold mostly low-risk assets) to exit a market that ordinarily has low trading volumes and idiosyncratic tranches,” the report said. “Such a shift could not only disrupt the CLO market but also adversely affect the functioning of the broader leveraged loan market.”

Overall, the report provides a useful overview of the massive U.S. credit market, whose participants include individuals, institutions, endowments, mutual fund companies, and foreign governments. At $54 trillion, the U.S. credit market is more valuable than the U.S. stock market ($35.5 trillion at mid-year 2020) and much larger than the value of U.S. Treasury securities held by the public ($16.8 trillion at end of 2019).

The global bond market has a current valuation of about $128 trillion, according to the International Capital Market Association. Of that amount, government bonds represent about two-thirds and corporate bonds about one-third.

With the Fed committed to holding interest rates down until 2023. (The Fed has, significantly, changed its inflation target to an average of 2% in the future, not a ceiling of 2%.) Investors, including life insurance investment committees, will continue to “reach for yield.”

The new breed of private equity-led life insurers with strong asset management partners will probably continue to do that by purchasing the senior “AAA” tranches of CLOs, adding perhaps 20 basis points to their added annual investment yield by doing so. Those 20 basis points, a mere fifth of one percent, may be the difference between successful companies and takeover targets in the years ahead.

© 2020 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.