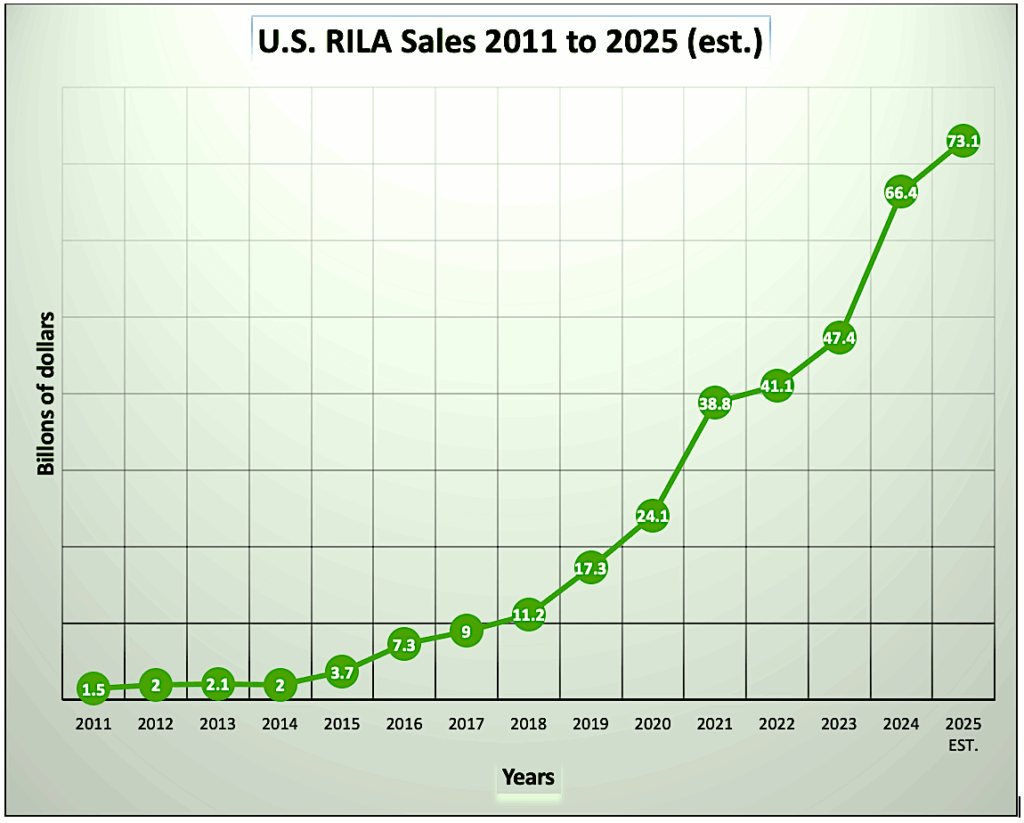

Registered index-linked annuities (RILAs)—structured products introduced by large life/annuity companies over the past 15 years—were originally marketed as sophisticated, conservative savings vehicles for people in their 40s or 50s.

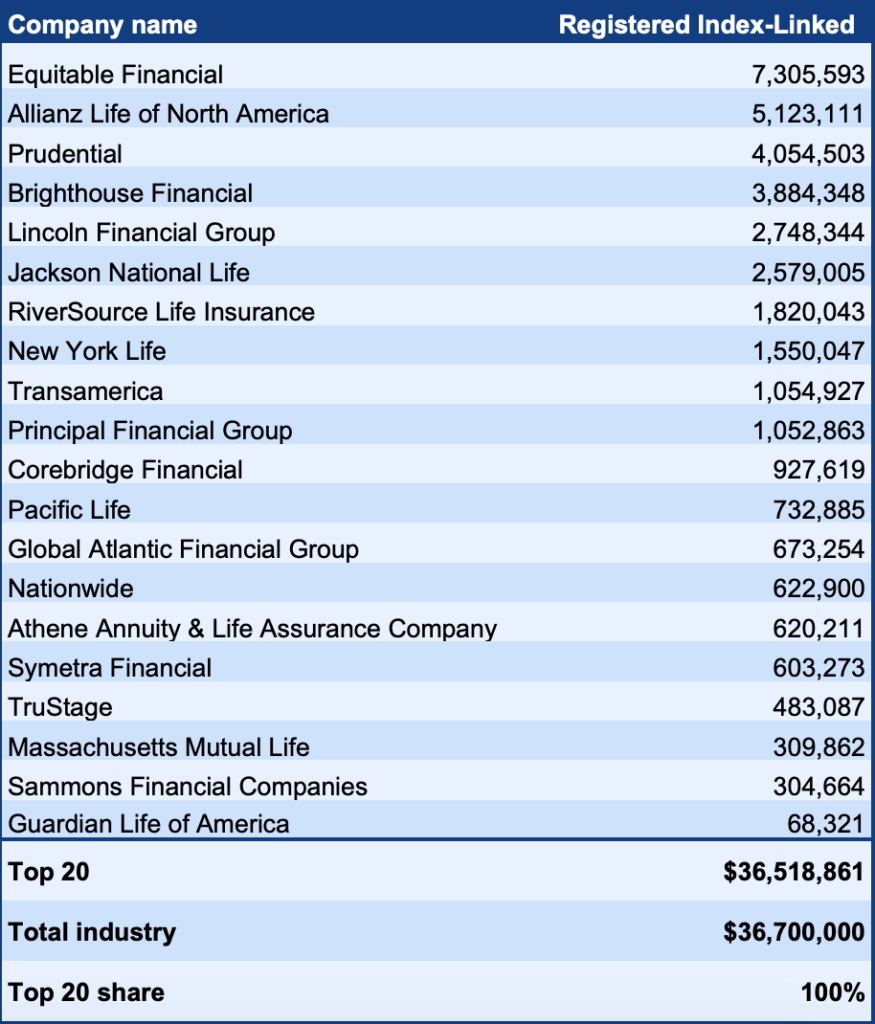

That original target market is now approaching retirement. It’s little surprise, then, that nearly half of the 20 principal issuers of RILAs have taken the next logical step and equipped their contracts with lifetime income riders. Demand for such riders has so far been modest but promising.

Sales of first half of 2025. Source: LIMRA.

“Most fixed index and RILA contracts are being bought without a GLB (guaranteed living benefit),” said Bryan Hodgens, senior vice president and head of LIMRA research, last year. “However, in recent quarters we have seen a slight uptick in consumers buying the GLB rider on FIAs and RILAs.”

In this issue of RIJ, we examine the income benefits on RILAs from nine insurers: the six largest RILA sellers (Equitable, Allianz Life, Prudential, Brighthouse, Lincoln, and Jackson) along with Principal, Pacific Life, and TruStage (part of CUNA Mutual Group).

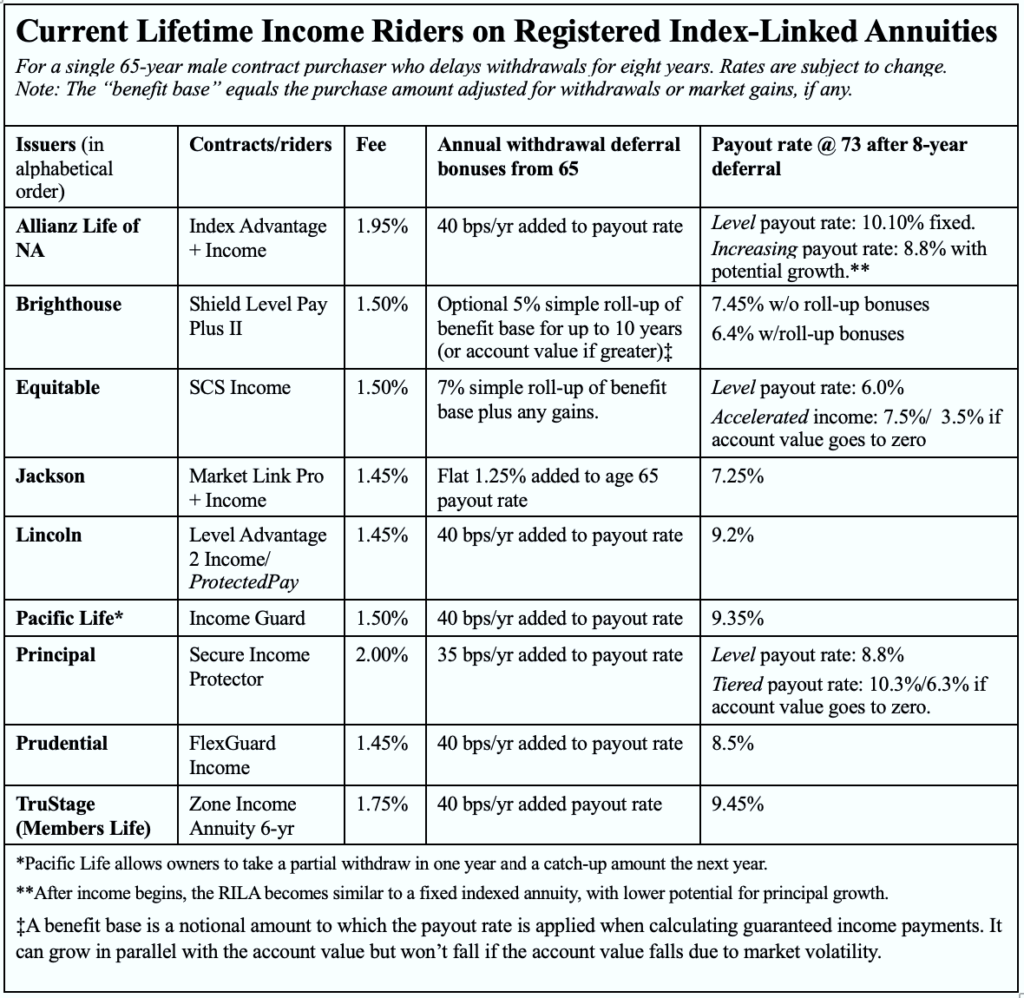

Rather than dissecting each rider—the details can be numbing—we asked a simple question: If a single man bought a RILA with an income rider at age 65 and waited eight years (until age 73, when the IRS begins requiring annual distributions from tax-deferred accounts) to activate his guaranteed lifetime income stream, what would his annual payout rate be?

We were particularly interested in the deferral bonuses: the annual increases in either the payout rates or the benefit base (a notional minimum accumulation amount) that issuers use to encourage contract owners to delay withdrawals. These often stop after 10 years and may be subject to waiting periods.

Source: Issuer websites.

Column four shows the annual deferral bonus on each rider. Two issuers (Brighthouse and Equitable) offer “roll-ups” (percentage increases of 5% and 7%, respectively) to the benefit base during the eight-year deferral period. Equitable’s roll-up applies to any annual gain in the contract’s value, while Brighthouse’s provides the greater of the roll-up or the actual gain.

Roll-ups were popular in the early 2000s but often confused buyers. Many mistook increases in the benefit base for guaranteed increases in their account value—essentially “free money.” In reality, the cash value remained exposed to market risk, while the benefit base was simply a notional figure used to calculate income payments.

Source: FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

The other seven income riders instead offer annual increases in the payout rate for each year income is deferred. For example, if the payout rate is 6% at age 65 and the deferral bonus is 40 basis points, the payout rate at age 73 (after an eight-year delay) would be 9.2% (6% + 8 × 0.40%).

Clients may not realize that deferral bonuses aren’t giveaways. They cost issuers nothing. The higher payout rate simply reflects the fact that the owner is older, and thus expected to collect payments for fewer years.

The far-right column of the chart highlights three riders that allow contract owners to fine-tune their payout at age 73. Allianz Life, for example, offers either a fixed payment equal to 10.10% of the account value or a lower initial payment (8.8%) based on an account value that continues to grow. The trade-off: the RILA effectively converts into a fixed indexed annuity, with reduced growth potential.

Making apples-to-apples comparisons of these riders is nearly impossible. Final payouts depend not only on market performance but also on the indexes chosen, the issuer’s crediting formulas, and the buffers or floors that limit potential losses.

Like FIAs, RILAs are structured products that generate yield through call options on equity indexes. FIA returns might range from 0% to 5%, while RILA returns can range from –10% to +10% or more.

As a rule, annuities with income riders have less upside potential than those without them. Rider fees drag on performance, and the guarantees require risk-management costs that further dampen yields.

In reviewing payout rates, I wondered how today’s RILA income benefits compare with the generous guaranteed lifetime withdrawal benefits (GLWBs) attached to variable annuities (VAs) in the early 2000s. Those riders fueled hundreds of billions in VA sales, but the 2008 crash and subsequent low interest rates exposed their risks, driving up costs and making them unsustainable.

Several of today’s leading RILA issuers were also major VA/GLWB providers 15–20 years ago (or are their corporate successors). It’s unclear whether RILA income riders are more conservative, but RILA returns are generally less volatile than VA returns—an important factor that should make the costs of RILA riders more predictable and manageable.

© 2025 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.