Making More Than Peanuts at MetLife

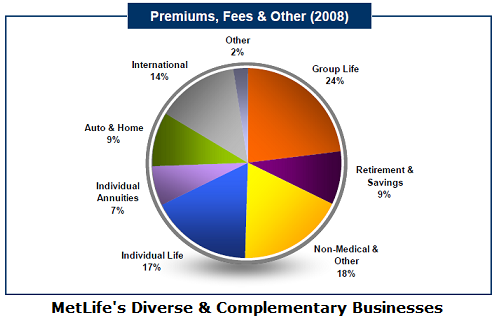

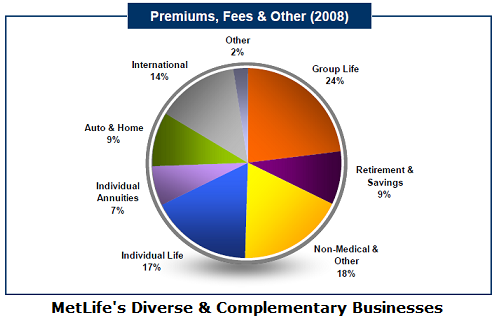

The financially fit, well-diversified insurer collected almost twice as much in annuity premiums as its closest competitor in the first quarter of 2009, benefiting from a “flight to quality” in the wake of last year’s economic meltdown.