The growing control of small and mid-sized publicly traded US life/annuity companies by giant global private equity (PE) companies has created “novel regulatory risks,” according to a document posted on the National Association of Insurance Commissioners’ website last month.

Noting “broad concern” about the PE trend, the document described the NAIC staff’s recommendations for addressing those concerns. For instance, the staff suggested creating a special category for the 177 PE-affiliated life insurers in the US for regulatory purposes and to make certain of their operations more transparent.

The document was used in a September 30, 2021 presentation at a regular meeting of the NAIC’s Financial Stability Task Force. The NAIC’s director of Structured Securities and Capital Markets, Eric Kolchinsky, delivered the presentation.

An NAIC spokesperson characterized the document as a “think piece” about “an issue that people have been monitoring.” NAIC staffers created it to inform the 56 state and territorial insurance commissioners they serve.

The document is notable for the policy changes that the staff suggests. Kolchinsky’s slides contained these suggestions to the insurance commissioners regarding regulation of PE owned life insurers:

- Define PE owned life insurers as “financial entity owned (FEO) insurers” who are controlled by or have long-term investment management agreements with financial firms that are not insurers and charge fees on assets under management (AUM) or for private credit origination.

- Broaden the definition of regulated “affiliates” to include firms managed by an affiliate of an FEO insurer, including managers of collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) or loans to companies owned by a CLO in an insurer’s portfolio.

- Strengthen affiliate reporting by demanding more transparent disclosure of fees paid to or accruing to affiliates. Also, require the disclosure of AUM of all affiliates, and identify the investments in the investment schedules where there are other relationships with affiliates.

The slides don’t mention reinsurance. That might surprise close followers of this trend, because the reinsurance of annuity liabilities in Bermuda or the Cayman Islands is an essential component of the PE insurance business model and an important new source of liquidity for a growing number of life insurers.

By reinsuring tens of billions of dollars in certain jurisdictions, PE firms can use Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) instead of Statutory Account Principles (SAP) to reduce the estimated cost of their long-term liabilities. All US life insurers must follow SAP, but certain jurisdictions allow the use of GAAP for reinsurance.

Doing so reduces the amount of capital that the insurer must hold in support of those liabilities. Reinsurance thus “releases” capital, in some cases making hundreds of millions of dollars available to the life insurance company. Holding extra capital enlarges the buffer of safety against loss for policyholders but represents a drag on the profitability of a life insurance company.

The pursuit of this strategy has put hundreds of billions of dollars worth of assets in motion over the past years, providing the substance of dozens of acquisitions and reinsurance transactions, putting vast pools of savings under the management of PE firms, and making life insurers more like asset management firms.

NAIC observations

In the document, the NAIC staff pointed out that today’s regulations were created for a life/annuity industry made up of publicly traded and mutual insurers, with an eye toward ensuring that insurance companies remained solvent and that owners don’t extract too much in dividends or compensation.

PE companies got into the insurance business to gain access to large new pools of of assets, and they generate profits by charging fees to manage those assets and redirect them into sophisticated alternative assets. But today’s insurance regulations lack mechanisms for observing and determining how those fees are generated or if they are reasonable.

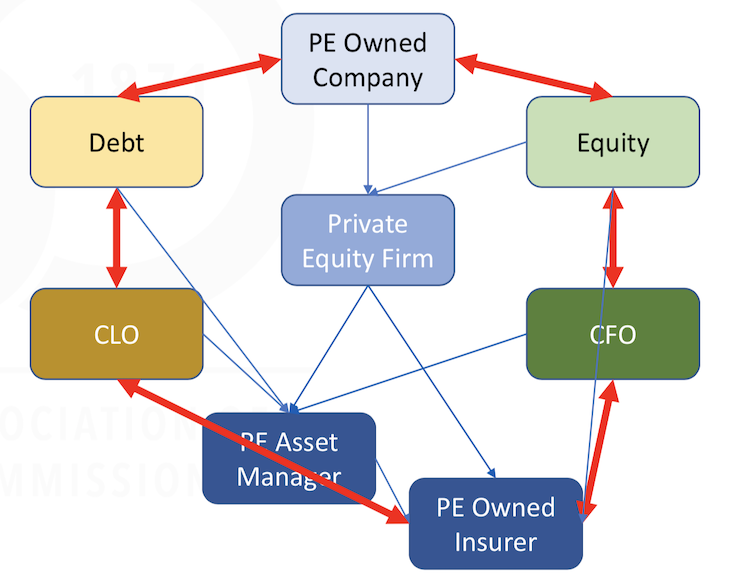

In short, a new kind of life insurance company has been born and regulations have not kept up with it. The PE business model has transitioned over the years from restructuring companies for profit to fee generation,” the document said. “PE companies seek to generate fees at every level of their investment from the underlying corporate to CLOs to managing assets for insurers.”

Not all of those levels are visible to regulators, especially when they are internal to the PE firm, which may obscure their relationships to affiliated entities. “It is common for PE owned firms to report affiliated managed CLOs [consolidated loan obligations] and structured products as ‘unaffiliated’ …We found that for one large insurer group that approximately 70% of their CLOs hold some exposure to their portfolio companies.” A large PE firm may have thousands of subsidiaries.

Forensic accountant Tom Gober is one of those concerned about the impact of PE firm involvement on the life/annuity industry. Gober scrutinizes life insurance regulatory filings to see if insurers or reinsurers have enough high quality assets backing their liabilities.

“I was delighted to see the NAIC step up and begin tackling this issue of PE-owned life insurers. Everything they said is so important; but perhaps most important is their discussion of Affiliated Transactions,” Gober told RIJ after seeing the Kolchinsky slides.

“In my 35 years of experience, the substance of all troubles I’ve investigated spin out of unregulated affiliates—not within the insurer itself. Special purpose vehicles, off-balance sheet deals, and captives are all only truly understood when you analyze both ends.”

Historical perspective

For those unfamiliar with these issues, here’s some background:

Ever since the private equity firm Apollo established the life/annuity company Athene over a decade ago, a stream of other large PE firms—including KKR, Blackstone, Ares, the Carlyle Group, Brookfield—have followed suit. They’ve used their deep financial resources to buy or partner with publicly traded insurers and to establish reinsurers, hoping to manage a chunk of the trillions of dollars in annuity assets—that is, the retirement savings of millions of Baby Boomers—in existence today.

In a series of articles over the past 15 months, RIJ has called this business model the “Bermuda Triangle” strategy. The strategy typically involves a life/annuity company, a reinsurer and an asset manager. Through the use of regulatory arbitrage and sophisticated loan origination skills, the strategy can reduce the cost of operating a life insurance company and raise the yield on its investments.

Blocks of fixed indexed annuity contracts are important to this strategy. Purchasers of FIAs often leave their money with an insurer for five, seven or even 10 years. Annuity issuers can turn that money over to asset managers to make loans to high-risk borrowers.

The PE firms typically bundle such “leveraged loans” into long-dated securities of varying risks and yields. They can sell those securities to institutions who want long-term investments that are as safe as high-quality bonds but have higher yields. This process turns the insurance business into an asset management business.

Such alchemy has, in a real sense, meant financial salvation for small and mid-sized publicly traded life insurers whose primary business is selling annuities. The Federal Reserve’s low interest rate environment has made it nigh impossible for these firms to generate enough profit via the old-fashioned way. That is, by investing policyholder premiums in high-grade corporate bonds to maturity and earning enough yield on them to cover claims, expenses, and profits for shareholders.

With the Bermuda Triangle strategy, these life insurers can also move capital-intensive liabilities offshore, release hundreds of millions of dollars of surplus capital that they can use to buy back their own stock, raise executive compensation, price their annuities more competitively, and evolve into the kind of fee-generating businesses that Wall Street analysts and investors prefer.

But while Wall Street and affected life insurers applaud this transformation of their businesses, the Bermuda Triangle strategy has critics. As early as 2013, researchers Ralph Koijen and Motohiro Yogo, raised flags about the wide use of captive reinsurance by major life insurers to offset the costly increase in their capital requirements in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis.

In their paper, “Shadow Insurance” (NBER Working Paper 19568), Koijen and Yogo warned that “life insurers are using reinsurance to move liabilities from operating companies (i.e., regulated and rated companies that sell policies) to less regulated and unrated off-balance-sheet entities within the same insurance group.”

More recently, a group of Federal Reserve economists published “Capturing the Illiquidity Premium.” The economists expressed concerns about the increasing use of life insurer money to finance the origination of private debt by their asset manager partners. This business model, they asserted, might be vulnerable to failure during a financial downturn.

© 2021 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.