At a presentation a few years ago, Peng Chen, president of Ibbotson Associates, projected a slide that plotted the positions of several retirement income products on a risk/return diagram.

In the northwest corner of the chart, as lonely as Pluto on a black map of the solar system, stood the immediate variable annuity (IVA). All other factors held equal, the IVA’s reward-to-risk ratio was highest. Yet no one ever buys it.

Lorry Stensrud wants to change that. Or rather, he still wants to change it. Just a few years ago, as an executive at Lincoln Financial Group, he championed Lincoln’s fascinating but complex i4Life deferred variable income annuity.

Now, as CEO of Chicago-based Achaean Financial, he’s back with a new, patent-applied-for customizable IVA chassis that he calls IncomePlus+. He wants to license it to life insurers, who he hopes will use it as the “Intel Inside” for a new generation of guaranteed income products.

Stensrud, who is 60, thinks that investors, asset managers, plan sponsors, and advisors are ready for an IVA that’s financially engineered to provide a cash refund or a death benefit. But first he has to convince life insurers to believe in it. He hopes they’ll see it as a magnet for new sales and a broom to sweep costly VAs off their books.

He claims to be winning that battle. “The life insurers’ first reaction is that it’s too good to be true,” Stensrud told RIJ. But when they learn more about it, he said, they warm up. “Their next question is, ‘Will the distributors and investors buy it?’”

How it works

So far, Stensrud has been careful about revealing how the product works, partly to protect his intellectual property and partly because different life insurers are expected to customize it in different ways.

Based on his description, however, it’s clearly not as simple as a plain vanilla IVA, which offers a payout that varies up or down from a starting payment that’s usually based on an assumed interest rate (AIR) of about 3.5%. Contract owners can often tinker with the asset allocation and there are no refunds or death benefits.

IncomePlus+ is more complex. It uses a zero-percent AIR so that the first payment is unusually low. Subsequent payments can never go lower than the initial one. On the other hand, there’s a payment cap, and excess earnings go into a reserve fund. It has a “bi-directional” hedging program includes both puts and calls. And it offers a cash refunds (whole or partial) and/or a death benefit that can be enhanced by assets in the reserve fund.

That’s a lot to digest. But, bottom line, on a $100,000 premium, IncomePlus+ would pay a single 65-year-old male about $570 a month to start with a rising floor and ceiling.

“At first we thought we needed to be within 5% to 10% of a SPIA payout rate, and that if we added upside potential we would be competitive,” Stensrud said. “But the distributors told us that nobody buys a SPIA at 65. They’ll compare us with systematic withdrawal plans (SWPs), so the payouts only need to be in the five percent range. A lower starting payment also means we can give larger increases when we have positive performance.”

A textbook SWP pays out 4%, or $333 a month per $100,000. (Without eating principal, of course.) A life-only IVA with a 3.5% AIR would pay about $616 a month initially, and fluctuate with the markets. A life-only SPIA would pay a flat $654 a month, according to immediateannuities.com. A SPIA with an installment refund would pay a flat $619 a month.

A variable annuity with a GLWB, by contrast, would pay just $417 a month to start. But most investors arguably regard that product primarily as an investment, and regard the income option less as a “full-size tire” than as a “donut” spare that they keep in the trunk for emergencies. In other words, they don’t necessarily have the same expectations of the income component that a SPIA or IVA buyer would. So it’s an apples-to-oranges comparison.

(Additional information about IncomePlus+ can be found in Stensrud’s interview in March with Tom Cochrane of annuitydigest.com, “Achaean Financial is Proving Innovation is Alive and Well in the Annuity Business.”)

Is the timing right?

Life insurers, or at least certain life insurers, will be receptive to his product, Stensrud believes, because it might help them free up some of the statutory reserves that they’re currently dedicating to underwater GLWBs. If they add IncomePlus+ as a settlement option to those contracts and persuade even a fraction of in-the-money policyholders to use it, they’ll save a lot, he said.

Insurers will also like IncomePlus+ because it’s reinsurable, which can’t be said for GLWBs, according to Stensrud: “The reinsurance aspect is important for most life companies. If they need to offload the business they have the opportunity to do that. There isn’t reinsurance available on any GLWB in the country.”

Others wonder if Stensrud’s reading of the marketplace is accurate. “I’m not sure if there are a lot of GLWB issues trying to find a way to get those contracts off their books,” said Jeffrey Dellinger, author of Variable Income Annuities (Wiley Finance, 2006) and a former colleague of Stensrud’s at Lincoln Financial. “It’s too soon to tell if there’s a demand for what Lorry is selling.”

Income annuity purists like Moshe Milevsky, meanwhile, wonder why some people are still determined to add liquidity to income annuities, when doing so only compromises their income-generating power, which arises from mortality pooling.

“The only free lunch in the annuity business is mortality credits,” said the Toronto-based academic and author of The Calculus of Retirement Income (Cambridge University Press, 2006) and other books. “If you are willing to give up dinner when you die, you can get a better lunch. These mortality credits increase with age and can be fused onto either variable investments and/or fixed investments. End of story.”

On the other hand, the primary audience for IncomePlus+ isn’t purists, and it isn’t even investors at this point. The audience is life insurers, asset managers, and financial advisors, and Stensrud thinks that many of them are looking for a product that’s somewhere between the GLWB and the SPIA.

The assumption underlying Stensrud’s strategy is a conviction that the variable annuity with a typical GLWB can’t deliver rising income in retirement under most circumstances. Indeed, even GLWB manufacturers concede that high fees and annual distributions are likely to stop the underlying account balance from reaching new high water marks, which are a prerequisite to higher payouts. But a properly engineered IVA can produce rising income, Stensrud thinks, and do it at lower risk and lower expense than a GLWB while still providing liquidity.

It may not be as simple or as elegant as a barebones IVA, or offer as much upside as one. But, historically, those don’t sell.

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

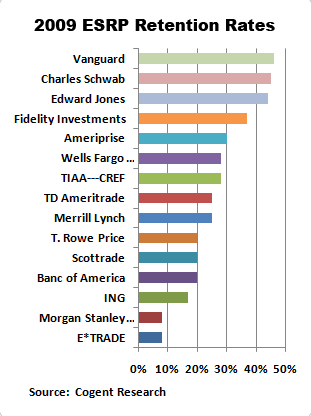

The ESRP providers with the highest retention rate (percentage of customers likely to choose the same firm as their IRA custodian are Vanguard (46%), Charles Schwab (45%), Edward Jones (44%) and Fidelity (37%).

The ESRP providers with the highest retention rate (percentage of customers likely to choose the same firm as their IRA custodian are Vanguard (46%), Charles Schwab (45%), Edward Jones (44%) and Fidelity (37%).