A year and a half after the collapse of the financial markets—and only days after the SEC charged Goldman Sachs with fraud—the debate about necessary “reforms” is still in its early stages, and none of the debaters seriously claims that his or her solution will in fact prevent a new crisis.

The problem is that the proposed remedies deal with superficial matters of industrial organization and regulatory procedure, while the real problems lie on a more profound level.

Banking has always been a business where the profits come over time, as the borrower pays interest on the loan and eventually repays the principal. Principal being much larger than interest, lending officers are paid to have good judgment about which applicants for loans can and will pay what they owe (and which debtors can’t or won’t)—especially on longer loans like mortgages, where one borrower who defaults eats the profits from ten or even twenty of those who pay.

The late Hyman Minsky, whose “financial stability hypothesis,” written in 1966, accurately described what happened to our banks a year and a half ago, liked to say that there was a morality to the lending officer’s work because his prosperity depended on the success of his clients.

In years past, loans were funded from the deposit base of the bank. Bank deposits are the transaction balances of the economy. Banks had the use of this money because they provided the plumbing of the payments system. Their size was determined by the needs of enterprise. Banks could not grow on their own motion; they were forbidden to borrow (except by discounting their customers’ paper) or to acquire bonded indebtedness.

Advertisement

In the 1950s, the banks began to free themselves from these shackles. What was then Morgan Guaranty established a market for Fed Funds, in which banks “bought” the excess reserves of other banks overnight or for very brief periods. In the 1960s what was then National City Bank of New York began to sell “certificates of deposit” to increase the money available to the bank for lending.

In 1975, I published a book that opened with the words, “A spectre is haunting American business and government: the spectre of banking.” Once the banks could grow by tapping the money markets they controlled, the government was not well equipped—or, to be honest, well motivated—to stop them. What slowed the march of finance was the fact that the profits came at the end of the loan, which had to be financed as long as it lived.

Enter “securitization.” Instead of keeping their loans in their vaults, banks could contribute them to packages of like instruments for sale to investors. Now the money came back to the bank long before the borrower repaid his loan. Absent specific arrangements for “recourse,” the bank didn’t necessarily care whether or not the loan was repaid.

To quote George Shultz, who was an economics professor before he was Secretary of State, the bank no longer had “skin in the game.” The lending officer’s work was supplanted by machines doing complicated and often unrealistic statistical analysis of which loans were likely or unlikely to default.

Moreover, bankers saw no need to make it easier for purchasers to value these pseudo-bonds by limiting the kinds of instruments that could be agglomerated in each “collateralized debt obligation.” The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, when cleaning out the S&Ls in the late 1990s, developed the idea of selling “the whole bank” by combining mortgages, credit card advances and business loans in “asset-backed securities.”

Historically, any paper with such characteristics had been “overcollateralized.” That is, it had been backed by loans with total asserted valuations greater than the face value of the bond. The FDIC, working through its subsidiary, the Resolution Trust Corporation, offered another step. If some of the collateral in the initial offer went sour, the FDIC made it possible for the packager of the paper to get a second chance, substituting other assets in the RTC warehouse.

This led to the “total return swap,” and then to the infamous “credit default swap,” an insurance policy disguised as a security. It gave all the little gamblers at the big dice table the opportunity to bet on or against the solvency of some company or government, whether or not they were rolling the dice themselves.

For the participants, these “innovations” were wildly successful. Their triumph, Michael Lewis suggests in his new book, The Big Short, was that the whole world became willing to lend money to instruments—not to businesses or houses, not to land, labor or enterprise, but to artificial contracts created behind closed doors.

The share of the financial sector in the nation’s gross domestic product rose from less than three percent in the decade after World War II to more than seven percent in the first decade of the new millennium. The share of the financial sector in the profits of corporate America grew even more rapidly, to more than 40 percent. The rest of us didn’t do so well.

The labor on Wall Street now is to restore those lovely unexamined days. And Wall Street will pay Washington lavishly—indeed, has already done so—to be of assistance in this effort. We are well on our way to reproducing the disasters of 2008.

Controlling the internal operations of the giant banks is all but impossible, but we can limit their intake and thus their size. Forty years ago, Scott Pardee, then the chief foreign exchange trader for the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, suggested a Food and Drug Administration for financial instruments, with a rule that instruments could not be traded by federally insured institutions unless and until they had a certificate that they were harmless.

Harvard Law professor Elizabeth Warren, chair of the House Subcommittee supposedly policing the government’s solicitude for “troubled assets,” recently offered a similar proposal. The grounds for rejecting would be that the instrument allowed banks to increase their leverage behind the scenes or to book profits from loans the borrowers had not yet repaid.

It’s worth a try. No doubt such a program would stifle innovation, but that’s all right. Honest men can disagree about whether we can afford universal health care, wars in the Hindu Kush, or reduced carbon emissions. But after seven trillion in losses that the taxpayers of the world must find a way to finance, it should be noncontroversial that we can’t afford any more innovation on Wall Street.

Martin Mayer, a guest scholar at The Brookings Institution, is the author of 34 books, including four best sellers—Madison Avenue, USA (1958), The Schools (1961), The Lawyers (1967) and The Bankers (1975).

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

Pfeifer defined “reasonable profitability” as about 10% a year. “If you think you can manage to 20% returns, you’ll be disappointed,” he said at LIMRA’s conference. An estimated 350 insurance professionals attended the conference.

Pfeifer defined “reasonable profitability” as about 10% a year. “If you think you can manage to 20% returns, you’ll be disappointed,” he said at LIMRA’s conference. An estimated 350 insurance professionals attended the conference.

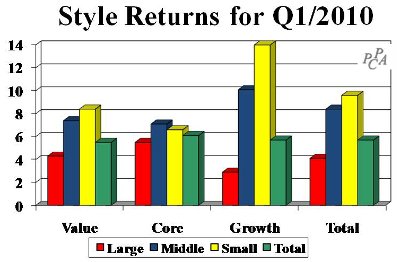

Now let’s look outside the US. While 2009 market performance far exceeded domestic returns, the first quarter of 2010 was a different story. Foreign markets earned 6.7% in local currencies but only 2.9% in US dollars, about half the US market return, as the dollar strengthened against other currencies.

Now let’s look outside the US. While 2009 market performance far exceeded domestic returns, the first quarter of 2010 was a different story. Foreign markets earned 6.7% in local currencies but only 2.9% in US dollars, about half the US market return, as the dollar strengthened against other currencies.  For S&P 500-based portfolios, for instance, we provide the following PODs. Use this table and graphic in the meantime to evaluate your investment managers. (Performance numbers for periods ending 3/31/10 are available now, but most peer groups won’t be released for a month.)

For S&P 500-based portfolios, for instance, we provide the following PODs. Use this table and graphic in the meantime to evaluate your investment managers. (Performance numbers for periods ending 3/31/10 are available now, but most peer groups won’t be released for a month.)