Lifting the Lid on the ‘Crypt’: A Rare Peek into the Bitcoin Universe

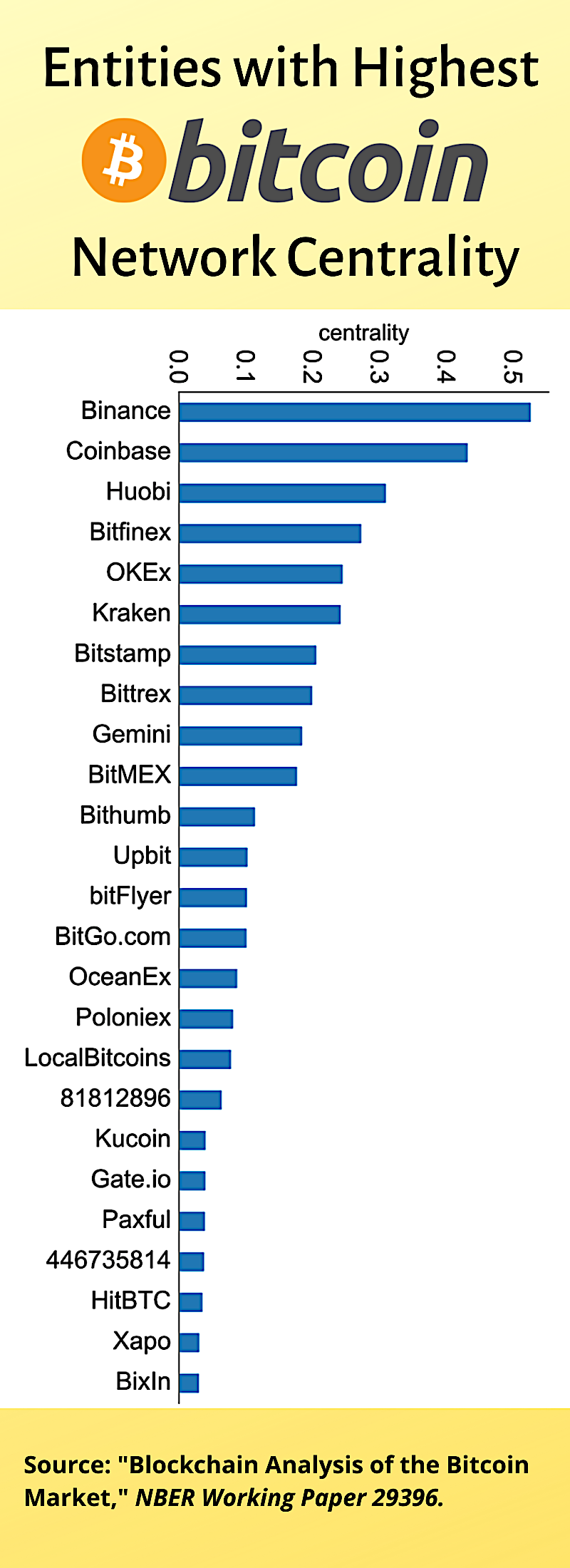

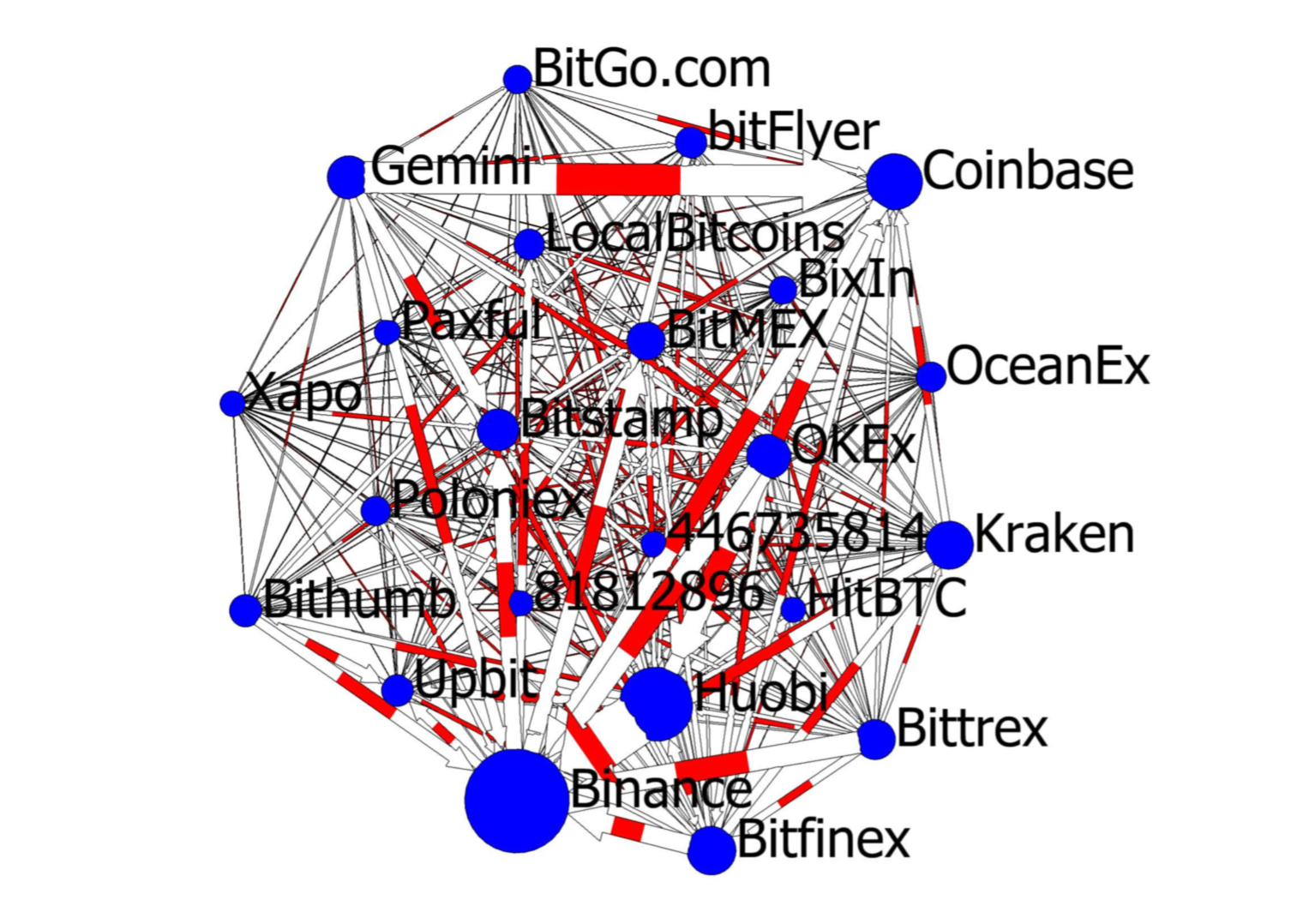

Cold wallets, hashing power, Chinese miners, 51% attacks, Satoshi Nakamoto, Kaiko data, peeling chains, the Hydra Market, and eigenvector centrality. These are just a few examples of the exotic vocabulary of the world of cryptocurrencies, including Bitcoin, the one most heavily traded.

A new article from the National Bureau of Economic Research offers a rare academic peek into this opaque world. Blandly titled, “Blockchain Analysis of the Bitcoin Market,” the article asserts that the Bitcoin universe is a noisy place, dominated by speculative and willfully redundant trading, with concentrated ownership of the coins. Money laundering and tax evasion represent a relatively small percentage of total trading volume, the researchers found. But it still represents a sizable sum of money.

The irony of cryptocurrencies is that, while the blockchain—the ledger that records cryptocurrency transactions—is available for all to see. Bitcoin users find ways to make it opaque—by using fake names and generating a fog of “spurious” trades.

“Many Bitcoin users adopt strategies designed to impede the tracing of Bitcoin flows by moving their funds over long chains of multiple addresses and splitting payments among them, resulting in a large amount of spurious volume,” write authors Igor Makarov of the London School of Economics and Antoinette Schoar of MIT.

The Bitcoin network, with clusters receiving >500,000 bitcoins from 2018 to end of 2020.

“Ninety-percent of transaction volume on the Bitcoin blockchain is not tied to economically meaningful activities,” they add. Instead, transaction volume is a byproduct of the Bitcoin protocol design, the participants yen for anonymity, and speculation in Bitcoin.

Speculation accounts for most Bitcoin activity, the authors concluded. But they suggest that traders may be hurt more by the opacity of the Bitcoin exchanges. “In contrast to traditional, regulated equity markets, the cryptocurrency market lacks any provisions to ensure that investors receive the best price when executing trades,” they write.

The authors estimate that illegal activity represents only 3% of Bitcoin activity, but that’s still a lot of money. “We calculate that there are about $550 million flowing to addresses that have been identified as scams, about $16 million in identified ransom payments, and more than $1.6 billion for dark net payments and dark net services. In addition, there are about $1.7 billion flowing to addresses affiliated with gambling and another $1.4 billion in mixing services.”

Many people own a little Bitcoin, but a handful of players own a lot. “The balances held at intermediaries (Bitcoin exchanges, online “wallets”) have been steadily increasing… By the end of 2020 it is equal to 5.5 million bitcoins, roughly one-third of Bitcoin in circulation. Individual investors collectively control 8.5 million bitcoins by the end of 2020. The top 1000 investors control about 3 million Bitcoin and the top 10,000 investors own around 5 million Bitcoins.

“This inherent concentration makes Bitcoin susceptible to systemic risk and also implies that the majority of the gains from further adoption are likely to fall disproportionately to a small set of participants,” Makarov and Schoar said.

‘Participating Longevity-Linked Annuities’ versus Conventional Drawdown Methods

Participating Longevity-Linked Annuities (PLLAs) are products that European pension experts have been studying. These group annuity products call for the sharing of longevity risk and market risk between the life insurers who issue annuities and the retirees who buy the annuities as a way to increase initial payout rates.

The strategy relies on options. “The embedded longevity put (call) options give the annuity provider (annuitant) the right to periodically adjust the benefit payments downwards (upwards) if the observed survivorship rates are higher (lower) than those predicted at the contract initiation, transferring part of the longevity risk to the annuitant.”

In a recent research paper, “Drawing Down Retirement Financial Savings: A Welfare Analysis using French Data,” two European pension economists, Jorge M. Bravo and El Mekkaoui Najat, test the effectiveness of a PLLA contract against seven common retirement drawdown methods. They find that a PLLA competes well.

Their paper, published in the Journal of the Association of Computing Machinery, investigates the individual welfare generated from eight alternative drawdown strategies, including four investment based solutions and four solutions using annuities:

- A self-managed fixed drawdown rule based on cohort life expectancy estimated at contract inception

- A self-managed non-insurance fixed drawdown rule based on the life annuity factor computed at contract initiation

- A self-managed variable drawdown rule based on a dynamic assessment of the remaining cohort life expectancy

- The “4%” Safe Withdrawal Rule (SWR), where households consume each year 4% of the initial wealth adjusted for observed CPI inflation

- Apply entire financial savings to purchase of a participating longevity-linked life annuity (PLLA)

- Purchasing a fixed single premium nominal life annuity (SPLA) at retirement age;

- A hybrid strategy allocating 70% of the retirement wealth to the “4%” SWR rule and the remaining 30% to an advanced life deferred annuity (ALDA) with a 15-year deferment period;

- Purchasing an inflation-protected annuity (IPA) at retirement

“Among the full annuitization strategies, the highest nominal and inflation-adjusted average consumption (and welfare) values are generated by the PLLA contract, followed by the IPA structure,” the authors found. “The income and consumption volatility of PLLA benefits is naturally higher than that of fixed annuities with annuity payments variability bounded at 20% of the initial benefit, but consumption levels are higher.”

When Dividends are Higher than Bond Yields, Do This

In the ultra-low interest rate environment that has prevailed (except in 2017-2018) since the Great Financial Crisis, individuals, insurance companies and institutions have “reached for yield” in excess of what high-quality bonds are paying.

Writing in the Journal of Wealth Management this year, respected academic researcher David Blanchett (who recently left Morningstar for Prudential), makes the case for substituting stocks for bonds as a source of retirement income when dividend yields exceed bond yields.

“The current yield gap environment today is relatively unprecedented, with dividend yields significantly exceeding bond yields in effectively every developed market. This anomaly suggests existing research on optimal income portfolios may need to be revisited, especially the structural decision of whether (and how) income-focused investors should consider allocating to equities.”

Blanchett told RIJ that his dataset allowed him only to compare stocks to bonds, not dividend-paying stocks to bonds. “In theory, if you’re allocating to stocks, you could allocate to those with higher dividend yields to generate more yield. You could also tilt the bond portfolio towards higher yielding bonds as well (e.g., corporates, especially high yield). My analysis is focused on the broad asset class decision, versus more nuanced asset class weights,” he said.

Dividends are a time-honored source of income for affluent retirees who never intend to liquidate their blue chip stocks, regardless in fluctuations in value. They bequeath the shares, taking advantage of the step-up in basis at death. Middle-class retirees rarely own enough equities to rely on the dividends for a significant portion of income. Retirement guru Wade Pfau sees no overall gain from buying equities for income, because the distribution of dividends coincides with a drop in the share price.

But after analyzing a database of bond yields and dividend yields in 17 different countries between 1870 and 2015, Blanchett sees a case for equities over bonds when bond yields are lower than dividend yields. He concedes that re-allocation to equities will raise the risk of a retiree’s portfolio and doesn’t recommend going “all in” to equities, recommending “a more measured approach.”

The Annuity Puzzle, Solved (More or Less)

Even though the “annuity puzzle” isn’t really so puzzling, academics continue to ask: Why don’t more Americans buy retail annuities. The most obvious answer is that they already contribute to and own annuities; it’s called Social Security. They fund it over a lifetime, which is the least painful way to pay for a pension or annuity.

Second, because life insurers so often ask people to fund their annuities with lump sums, life insurers limit the annuity audience to those who can afford single premium payments of hundreds of thousands of dollars at or near retirement. That leaves out a lot of people.

In a new research paper sponsored by the Alliance for Lifetime Income’s Retirement Income Institute, financial literacy expert Annamaria Lusardi and others at the Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center in Washington, DC, document the roles that “liquidity constraints,” including “debt obligations,” put annuities out of reach.

“We find that many people who are in the retirement planning phase of the life cycle (individuals ages 40–61) and those who are of retirement age (individuals ages 62 and over) face these barriers to annuity ownership: Lack of financial knowledge, leveraged assets, debt obligations, and liquidity constraints are all likely barriers to annuity ownership.”

The team of authors found that “annuity owners are more likely to be older and wealthy, to have greater access to liquidity, and to experience higher levels of satisfaction with their financial situation than non-owners. Results indicate that having access to liquidity and letting a professional choose investments are both positively associated with annuity ownership.”

“While we do not find any significant relationship between financial literacy and annuity ownership,” they add, “results do indicate that financial literacy may lead to increased take-up rates through improving individuals’ access to liquidity.”

© 2021 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.