The financial crisis of 2008 will continue to hurt state and local government pension funds for at least several years, and a rebound in both the stock market and the economy may be required to restore them to health.

That is the assessment described in a new research brief from the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, entitled The Funding of State and Local Pension Funds, 2009-2013, by Alicia H. Munnell, Jean-Pierre Aubrey and Laura Quinby.

Funding ratios for public pensions could drop to 72% by 2013, from 78% in 2009, or as low as 66% under a “pessimistic scenario,” the authors said. At 72%, the funding shortfall could rise (in constant dollars) from $728 billion to about $1.2 trillion.

The study was based on 126 state and local plans representing about 90% of the universe of state and local plans. State and local pension plans currently have about $2.7 trillion in assets-enough to cover pension outlays for about 15 years on average even with no investment growth.

| A Snapshot of Public Pensions |

|

Roughly three-quarters of state and local government employees take part in an employer-provided pension plan. Around 80% of public employees have only a defined-benefit pension, 14% have only a defined-contribution pension, and 6% have both. Government employees typically receive benefits equal to around 2% of final earnings per year of employment. Some public sector employees take part in Social Security, while others are not covered by Social Security and receive their principal retirement income from their employer’s program. The average state employer contribution rate as of 2006 was 9.9 percent of employee salary, while the average employee contribution rate was 5.7 percent. As of 2006, around 60% of public-pension assets were held in domestic or foreign equities and slightly over 25% in bonds, with smaller allocations in real estate, cash, alternate investments such as private equity, or other asset classes. Public sector pensions tend to allocate around 10 percentage points more of their assets to equities than do private sector pensions. The share of public sector assets held in equities has risen from around 4% in 1990 to around 70% as of 2006. State pensions on average project future nominal returns of 8%; the lowest projected return for a state pension is 7% and the highest is 8.5%. Rates of return on plan assets are either projected by plan managers or established in statute. -Andrew Biggs |

“So there’s no immediate cash crisis,” said Munnell, the Center’s director. But she added that in some states public pensions could run short in as little as six or seven years.

“State and local governments are facing a perfect storm: the decline in funding has occurred just as the recession has cut into state and local tax revenues and increased the demand for government services. Finding additional funds to make up for market losses will be extremely difficult,” the brief says.

Nationwide, the funding shortfall will require states, on average, increase their annual pension fund contributions by about $400 per covered employee. Because of the shortfall, contributions for 2009 will be about 8% of state budgets, up from a historical average of 6%.

Others say the problem is much more serious, given the volatility of future market returns and the inability of states to modify their pension obligations. For instance, the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) estimated this month that the size of the state employee pension shortfall alone is more like $3 trillion.

That figure uses the 10-year Treasury rate as the discount rate for the obligations and adds the hypothetical cost of guaranteeing the obligations with put options in the financial markets.

Advertisement

Because governments may need to raise taxes to cover future pension obligations, the problem has become increasingly political, often characterized by resentment toward teachers and other state, county or city workers with public pensions.

“There is no reason public-sector employees should receive retirement benefits that are either larger or more secure than those received by private-sector workers,” wrote Andrew Biggs of the AEI. He recommends that new public sector employees be offered defined contribution plans instead of traditional pensions.

Munnell said that up until about 50 years ago, state and local governments did little in the way of formal funding of their employee pension plans. But after the Baby Boom created a surge in demand for public school teachers in the 1960s, and a big increase in pension commitments, the funding issue got more attention.

According to CRR, it was said in the mid-1970s: “In the vast majority of public employee pension systems, plan participants, plan sponsors, and the general public are kept in the dark with regard to a realistic assessment of true pension costs. The high degree of pension cost blindness is due to the lack of actuarial valuations, the use of unrealistic actuarial assumptions, and the general absence of actuarial standards.”

In the 1990s, with the creation of a Governmental Accounting Standards Board, benchmarks were established. The funding ratio continued to improve until the financial crisis of 2008. The CRR researchers noted that states and municipalities don’t have many options to respond to the pension dilemma. For various reasons, they can’t raise employee contributions or earned benefits. Because of the recession, tax revenues are down and demand for services are up.

“One small step… would be for states and localities to at least pay their full Annual Required Contribution,” which the Governmental Accounting Standards Board defines as the an amount needed to cover the cost of benefits accruing in the current year and a payment to amortize the plan’s unfunded actuarial liability. “Otherwise, the only option is to wait for the market and the economy to recover.”

The future health of state and local pensions “depends increasingly on the future performance of the stock market. Under the most likely scenario, the funding ratio will continue to decline as the strong stock market experienced in 2005, 2006, 2007, and much of 2008 is slowly phased out of the calculation.”

The AEI’s Biggs made the following recommendations for public pensions:

- Pensions must disclose greater detail regarding investment risk. These details should include the volatility of their investments and the co-variances of returns between different elements of their portfolios.

- Actuarial firms contracted by pensions should calculate the probability that plan assets will be sufficient to meet obligations, such as is currently done for Social Security by the plan’s actuaries and by the Congressional Budget Office.

- Second, pension plans should reform their accounting methods to include the market value of plan liabilities.

- Employee contribution rates should be increased and eligibility for retirement delayed. Where possible, the rate at which future benefits are accrued should be reduced. For instance, most plans currently pay 2% of final salary per year of service; while accrued benefits should be honored, future benefits could be earned at a lower rate.

- States should no longer put off their own pension contributions. Each state must do the maximum to restore its plans to solvency. For newly hired employees, public sector pensions should shift to a defined contribution basis to make them more comparable to plans offered in the private sector.

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

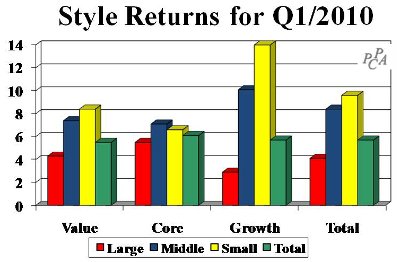

Now let’s look outside the US. While 2009 market performance far exceeded domestic returns, the first quarter of 2010 was a different story. Foreign markets earned 6.7% in local currencies but only 2.9% in US dollars, about half the US market return, as the dollar strengthened against other currencies.

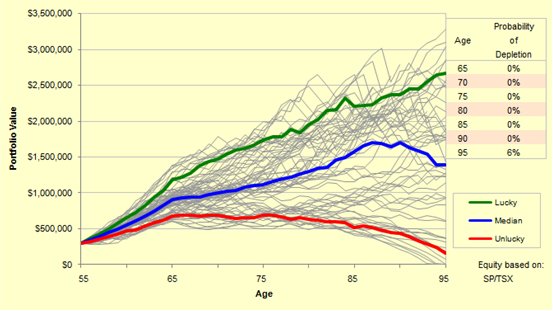

Now let’s look outside the US. While 2009 market performance far exceeded domestic returns, the first quarter of 2010 was a different story. Foreign markets earned 6.7% in local currencies but only 2.9% in US dollars, about half the US market return, as the dollar strengthened against other currencies.  For S&P 500-based portfolios, for instance, we provide the following PODs. Use this table and graphic in the meantime to evaluate your investment managers. (Performance numbers for periods ending 3/31/10 are available now, but most peer groups won’t be released for a month.)

For S&P 500-based portfolios, for instance, we provide the following PODs. Use this table and graphic in the meantime to evaluate your investment managers. (Performance numbers for periods ending 3/31/10 are available now, but most peer groups won’t be released for a month.)

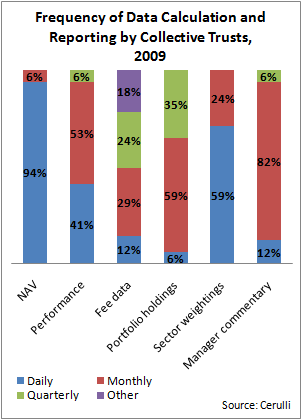

“Because [CTFs] are bank-registered products, you have an external fiduciary joining the plan sponsor,” he added. “Plan sponsors like that. If the asset manager is using a ‘40 Act’ [i.e., Securities Act of 1940] mutual fund format, there’s no co-fiduciary. From what we’ve heard, that makes the CTF an easier sell. We’ve also heard that Taft-Hartley plans [multi- employer union-sponsored DC plans] are more comfortable with CTFs.”

“Because [CTFs] are bank-registered products, you have an external fiduciary joining the plan sponsor,” he added. “Plan sponsors like that. If the asset manager is using a ‘40 Act’ [i.e., Securities Act of 1940] mutual fund format, there’s no co-fiduciary. From what we’ve heard, that makes the CTF an easier sell. We’ve also heard that Taft-Hartley plans [multi- employer union-sponsored DC plans] are more comfortable with CTFs.”

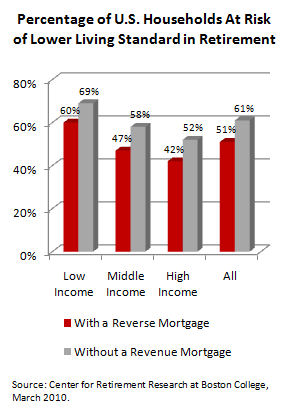

Retirees can generate funds from home equity by downsizing, or by borrowing against their home’s equity value. The reverse mortgage is a product specifically designed for retirees who wish to stay in their home and have access to its equity.

Retirees can generate funds from home equity by downsizing, or by borrowing against their home’s equity value. The reverse mortgage is a product specifically designed for retirees who wish to stay in their home and have access to its equity.

The program’s genesis

The program’s genesis