| Variable Annuity Provider Customer Loyalty Ranking | |

|---|---|

| 1 | TIAA-CREF Life Ins Co |

| 2 | Ameriprise Financial |

| 3 | Allianz Life Ins Co of NA |

| 4 | Fidelity Investments Life Ins |

| 5 | ING |

| 6 | Nationwide Life Ins Co |

| 7 | MetLife |

| 8 | John Hancock Life Ins Co (USA) |

| 9 | Jackson National Life Ins |

| 10 | The Hartford/Hartford Life Ins Co |

| Source: Cogent Research Investor Brandscape 2010 | |

Archives: Articles

IssueM Articles

In Search of Plan C

WASHINGTON, D.C.—Yesterday was Groundhog Day, the day that supposedly repeats itself ad infinitum, so it was fitting to hear assistant Secretary of Labor Phyllis C. Borzi say something that has been said many times before: that America has a retirement income problem.

“We have a crisis of confidence regarding retirement,” the Obama appointee and employee benefits expert said. She spoke at a half-day conference sponsored by the National Institute of Retirement Security, an advocacy group created by state and local defined benefit plan administrators about three years ago.

“Defined contribution plans used to be our Plan B, after defined benefit plans,” she continued. “But the past two years have shown that DC plans weren’t a silver bullet. We don’t appear to have a Plan C, other than Social Security. Our job is to come up with a Plan C.”

Borzi, who runs the DoL’s Employee Benefits Security Administration, has jurisdiction over some 700,000 private-sector retirement plans and 2.5 million health plans. She was the featured speaker at the NIRS event, which was called “Raising the Bar: Policy Solutions for Improving Retirement Security.”

The event drew a capacity crowd of some 250 people, most of whom work in public pensions, which are under siege because the recession has made it hard for states and taxpayers to fund them. The crowd came to hear speakers like Putnam Investments’ CEO Robert Reynolds, Harvard Law professor Elizabeth Warren, AFL-CIO president Richard L. Trumka and Roger W. Ferguson Jr., the president and CEO of TIAA-CREF.

Nothing startlingly new was revealed at the conference, which was held in the ornate Columbus Club, a one-time “fancy soda fountain” whose walls and ceiling now feature hand-painted Pompeian flowers, inside Washington, D.C.’s restored Union Station. But the event suggested that the issue of retirement income is gaining traction in the nation’s capitol.

Borzi’s presence, and the fact that the Labor and Treasury Departments also chose yesterday to publish a request for 90 days of public input about workplace annuities, seemed to signal that the Obama Administration has officially picked up the retirement income torch.

Compared with retirement income conferences sponsored by the financial industry, this one was distinctly more liberal in tone and sentiment. It reflected the world-view in which government officials are problem-solvers, unions are forces of good, and the welfare of the embattled middle class, rather than the most affluent quintile, take priority.

Nonetheless, Borzi, an attorney who had a reputation as a “fiduciary hawk” during her career as an academic and an ERISA lawyer, didn’t seem to underestimate the challenges her department faces in trying to put lifetime income options in retirement plans.

Borzi ticked off the many “technical and policy” issues that make it difficult to introduce lifetime income options into retirement plans, including questions about spousal consent, around the conversion rates for projecting a plan participant’s future income, or about public’s stubborn resistance to annuitization even when it is offered.

She made a point of saying that reform would not come at the expense of strong oversight. “Some academics say that, if we waived the fiduciary rules, plan sponsors would offer annuities in their plans. I can assure you that the fiduciary rules won’t be waived on my watch or on [Labor Secretary] Hilda Solis’ watch, but we want to find out how we can make it easier,” she said.

“Labor and Treasury are now looking at a lost feature of DB plans: the lifetime income stream. I use the phrase ‘lifetime income stream’ because I’m not hawking annuities. I don’t work for the insurance companies,” she was quick to point out, perhaps in recognition of the competition between the securities and insurance industries in the retirement market.

“But something has gone wrong, and we need to look for a means or a mechanism for people to enjoy retirement without fear,” she continued. “The 401(k) plan isn’t really a retirement system. You get money out when you change jobs. People either squander their lump sum payouts, or they treat it too conservatively because they’re afraid of outliving their money.”

In putting out a request for information, or RIF, yesterday, Borzi said, “We want to start a national dialogue or conversation to see if it’s a good idea to allow people to take a lifetime income stream” from 401(k) plans. “We want to find out if there are things we can do—products, regulations, legislation—or if we need to do anything at all.”

After the 90-day comment period, “We might have hearings. We might propose legislation. The administration is very interested in retirement security, so there may be administration initiatives,” she said, noting mordantly, “If you don’t know where you are going, any road will take you there.”

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

Firms Back Variable Annuity Product Launches With Aggressive Online Marketing Campaigns

No annuity product was hit harder during the financial crisis than variable annuities. Many variable annuity contracts saw significant drops in value, in many cases 30% or more, due to the products’ heavy exposure to the financial markets. For an investment that supposedly offers a guaranteed retirement income stream, variable annuities had been exposed as flawed and ultimately risky investment vehicles.

Despite the firms’ best efforts to evolve variable products to fit the new financial landscape, variable annuity sales remained flat throughout 2009 and were down significantly in contrast to 2008. In response to the lackluster sales numbers, firms have intensified their online marketing campaigns to the public, placing additional promotional muscle behind high-profile variable annuity product launches.

Fidelity and AXA Equitable have both released memorable, multi-faceted online sales campaigns for new variable annuities over the last three months. Fidelity’s November launch of the MGGI (MetLife Growth and Guaranteed Income) variable annuity was backed by homepage promotional imagery that integrated the firm’s flagship GPS campaign theme and linked to a comprehensive product page.

Fidelity and AXA Equitable have both released memorable, multi-faceted online sales campaigns for new variable annuities over the last three months. Fidelity’s November launch of the MGGI (MetLife Growth and Guaranteed Income) variable annuity was backed by homepage promotional imagery that integrated the firm’s flagship GPS campaign theme and linked to a comprehensive product page.

Aside from offering pertinent details about the MGGI variable annuity and a good selection of literature, the product page also features an engaging video and new product-focused calculator. The video is three minutes long and creatively highlights key product features and strengths using vivid imagery and audio commentary.

The MGGI calculator has an attractive, user-friendly interface and is easy to complete. After inputting age, lump sum investment value and market return, a hypothetical illustration displays the MGGI’s target income payments. The results can be viewed in a summary, chart or table.

The AXA Equitable Retirement Cornerstones variable annuity was introduced online in creative fashion in January. A relatively straightforward homepage image links to the Introducing Retirement Cornerstone sitelet, which contains an interactive cube that highlights key product features.

The interactive Retirement Cornerstone cube focuses on four areas – Tax Deferred Single Platform, Performance, Protection and Retirement Cornerstone. Product structure, key features, available underlying accounts, performance data and account management are clearly explained. Links to the Retirement Cornerstone product information page and related literature are offered in all four sections.

Over the last year, firms have worked tirelessly to mold variable annuities into safer, more cost-efficient retirement investments that pose fewer risks to both consumers and issuers. It is clear that aggressive and engaging online marketing campaigns will play a large role in selling prospective investors on variable annuities as reliable retirement income solutions.

© 2010 Corporate Insight, Inc. All rights reserved.

Industry Views are special reports that are sponsored and independent from RIJ’s editorial content.

Agencies Seek Public Input on Lifetime Income Options

The U.S. Departments of Labor and the Treasury want your advice on how to enhance retirement security for workers by including lifetime annuities or other arrangements as distribution options in employer-sponsored retirement plans. The request for information (RFI) appears in yesterday’s edition of the Federal Register.

“Today’s initiative is particularly important given the shift from defined benefit plans that offer employees lifetime annuities to 401(k) and other defined contribution plans that typically distribute retirement savings in a lump sum payment,” said Phyllis C. Borzi, assistant secretary for the Labor Department’s Employee Benefits Security Administration.

The RFI seeks comments on a broad range of topics, including:

- The advantages and disadvantages of distributing benefits as a lifetime stream of income both for workers and employers, and why lump sum distributions are chosen more often than a lifetime income option.

- The type of information participants need to make informed decisions in selecting the form of retirement income.

- Disclosure of participants’ retirement income in the form of account balances as well as in the form of lifetime streams of payment.

- Developments in the marketplace that relate to annuities and other lifetime income options.

Written comments responding to the lifetime income RFI may be addressed to the U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Regulations and Interpretations, Employee Benefits Security Administration, N-5655, 200 Constitution Ave. NW, Washington, DC 20210, Attn: Lifetime Income RFI. The public also may submit comments electronically by email to [email protected] or through the federal e-rulemaking portal at http://www.regulations.gov.

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

Putnam To Help Plan Participants Forecast Income

Putnam Investments has launched an online tool for 401(k) plan participants that will calculate how much they can expect to receive in monthly income after they leave the work force. The tool will initially be available only to Putnam’s plan sponsor clients and their employee plan participants.

Financial advisers will be able to use the tool within three months, Jeffrey Carney, a senior managing director and head of global marketing, products and retirement at Putnam, said at Putnam’s Retirement Income Summit in New York last week.

Unlike tools that require investors to input all their data in multiple steps to figure out what they will need to save for retirement, Putnam’s Lifetime Income Analysis Tool allows participants to go to its plan participant website and immediately see a monthly retirement income statement based on their current savings plan and account balance, according to Mr. Carney.

“Every time a participant logs in to the site, they will see their account balance as retirement income,” said Ed Murphy, a managing director and head of defined contribution.

Participants then can adjust different sliding rules to see how their retirement income would be affected if they increased or decreased their 401(k) contribution rate and their age of retirement.

Because the tool is integrated with 401(k) plan sponsors’ record-keeping systems, it will be more effective in helping participants take actions than other online services, said Dallas Salisbury, president of the Employee Benefit Research Institute.

“This tool has the ability to change how much someone is contributing to their plan in three clicks,” he said. “Last time I changed something in my 401(k) plan, it took 21 clicks.”

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

Pioneer In Life Settlements Calls It Quits

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. has shut down its life settlements provider, Longmore Capital, Investment News reported.

The move marks Goldman Sachs’s exit from the secondary life settlements market, said Michael DuVally, a spokesman for the firm. He said that the decision to shut down the life settlements provider was a “commercial decision.”

“When we entered in 2006, we thought the life settlements market had the potential to grow into a large institutional market, but at the present time we don’t see it growing beyond the size it has right now,” he added.

Goldman’s decision to shut down Longmore Capital arrives about a month after the investment bank’s decision to shut down its QxX mortality index.

Launched in January 2008, the QxX index tracked the lives of 46,000 people over 65 with a primary impairment (other than AIDS or HIV). Goldman followed that with the release of the QxX.LS.2 index in December 2008, with another pool of 65,655 people over 65 with conditions that included cancer and diabetes.

That market never took off, however, and industry observers said that few trades were made on the index.

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

ING to Help Retirement Professionals Grow Their Businesses

ING’s U.S. Retirement Services has launched a new program for advisors, consultants and the third-party administrators (TPA) who serve the small and mid-sized corporate retirement plan market.

Referred to as the ING Grow Program, the suite of practice development tools and resources is designed to help ING’s distribution contacts grow their business.

The resources offered in the ING Grow Program focus on three specific categories:

- Sales ideas and business-building tools to help grow relationships.

- Value-added thought leadership to keep retirement professionals up-to-date on important industry trends.

- Behavior-changing technology and educational applications to help participants become better prepared for retirement.

As part of the program, advisors, consultants and the TPA community will be able to offer clients an outline of their Statement of Services. This document will serve as a value proposition that describes the services they intend to provide and their philosophy relating to consulting, conversion and ongoing installation. Advisors may also include industry experience and qualifications, and customize the statement with a firm logo and contact information.

The program includes a series of ING practice management seminars on topics such as Fiduciary Responsibility and Trends in Retirement Plan Administration. They can also tap into the ING Institute for Retirement Research.

The new program also emphasizes the use of ING’s consumer education resources and web-tools, which can be leveraged at employee meetings and serve as catalysts for retirement planning discussions. These include participant seminars and three retirement planning calculators:

INGYourNumber.com. This can help calculate the total amount of money participants need to save by the time they retire.

INGCompareme.com. This harnesses the power of “peer comparison” to show users where they stand in relation to others on a wide range of saving, spending, investing, debt and personal finance matters.

My Retirement Outlook. This retirement and paycheck analysis tool integrates traditional pension plan assets, Social Security benefits and personal savings, and also identifies potential gaps in retirement funding. Participants can print an instant gap analysis statement.

ING’s U.S. Retirement Services, part of ING’s global insurance operations, has more than $285 billion in combined assets under administration and management.

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

To Insurers’ Relief, VA Owners Acted Inefficiently

Issuers of variable annuity living benefit riders did not come through the financial crisis unscathed. But the pain would have been worse if hordes of contract owners had decided to begin drawing guaranteed income while their account values were depressed.

But they didn’t. According to Ruark Consulting’s Variable Annuity Benefit Utilization Study, only one in five owners of contracts with guaranteed lifetime withdrawal benefit (GLWB) or guaranteed minimum income benefit (GMIB) riders took withdrawals. Of those, only one in three withdrew the maximum annual amount.

Seven insurance companies furnished data to Ruark for the study, including MetLife, AXA Equitable and Pacific Life. The study was based on three million contract years of data from January 2005 to June 2009, and the study encompassed about 25% of the variable annuity living benefit market.

To the extent that these results are incorporated into insurer’s assumptions about policyholder behavior and enable them to reduce estimates of risk exposure, the new data could mean that issuers can reduce their reserves for variable annuity income riders.

“If utilization went the other way, they would have to reserve more,” said Peter Gourley, an actuary and vice-president of Ruark Consulting LLC in Simsbury, CT. Surrender rates for the contracts went down as the contracts became in-the-money, meaning that owners were not letting insurers off the hook for the guarantees.

As at least one observer pointed out last year, savvy VA owners and their advisors could have made the most efficient use of their living benefits by starting their income benefits while the account values were down, and perhaps even using the income to buy equities at depressed prices. Few apparently did.

The study covered partial withdrawals under variable annuity contracts containing Guaranteed Living Withdrawal Benefits (GLWB), Guaranteed Minimum Withdrawal Benefits (GMWB) and Guaranteed Minimum Income Benefits (GMIB).

Withdrawal rates for owners of guaranteed minimum withdrawal benefits (GMWBs) were somewhat higher, with one in three owners taking withdrawals. The higher rate was attributed to the fact that most GMWB contracts lack the “roll-ups” or annual bonuses, common in GLWBs, which incentivize owners not to make withdrawals for as many as 12 years.

The Ruark study also showed that, as common sense would predict, utilization rates went up with the age of the contract owner. Tax qualified policies had higher usage than non-tax qualified policies.

The U.S. insurance industry established a new standard in 2009 for establishing statutory reserves on variable annuity business. Often referred to as VA CARVM, it is a principle-based reserve calculation, requiring companies to perform financial projections that utilize assumptions believed to be appropriate.

Insurance companies also establish allocations of their capital, above and beyond reserves, to support their variable annuity business. These allocations, known as Risk Based Capital, have been on a principle-based method since 2005.

This was Ruark Consulting, LLC’s first Variable Annuity Benefit Utilization Study. In combination with its Variable Annuity Mortality Study in 2007 and Surrender Study in 2008, the actuarial firm claims to have provided the first insights into variable annuity policyholder behavior.

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

SunAmerica Links VA Rider Fees to Volatility Index

SunAmerica, the AIG unit that bills itself as “The Retirement Specialist,” has launched two new variable annuity living benefits whose rider fees fluctuate with the VIX, the index of S&P 500 equity volatility at the Chicago Board Options Exchange.

By sharing some of the hedging risk with the contract owner, the insurer hopes to maintain a relatively generous bonus during the accumulation stage and payout rate during the distribution phase. SunAmerica has apparently not chosen to simplify or strip down its variable annuities, but to offer benefits as rich as possible while still “de-risking.”

Designed for the Polaris series of variable annuities, the two guaranteed minimum withdrawal benefits are called Income Plus 6% and Income Builder 8%. They have distinct but overlapping characteristics.

Both contracts encourage the contract owner to postpone withdrawals by promising to double the guaranteed income base (the purchase premium, initially, and the amount on which payouts will be based) if the contract is undisturbed for 12 years.

In addition, the Income Builder 8% allows owners to take withdrawals of up to 5.5% during the income stage. The income stage can begin as early as age 45. The rider is designed for individuals who want to rebuild their portfolios between now and the time they retire.

The Income Plus 6% allows withdrawals of up to six percent during the first 12 years, and clients’ income bases are credited with the difference if the withdrawal—a required distribution from a qualified plan, for instance—is less than six percent. The rider is designed for people who may be involuntarily retired and need to begin living on their savings.

But the novel aspect of the product is the fee structure. The initial fee rate of 1.1% (1.35% for joint and survivor contracts) is guaranteed for the first year. After that, it can fluctuate with the VIX by as much as 6.25 basis points per quarter or up to 25 basis points per year. But it cannot be higher than 2.2% for one person (2.70% for two) per year or lower than 0.60%. For every one percent change in the VIX, the fees move five basis points.

“We’re passing through the cost of the hedging to the owner so that we can add more value,” said Rob Scheinerman, senior vice president for product management at SunAmerica. “In the marketplace all the products have a variable fee structure. And we’ve seen a lot of riders move up in price. This product also has the ability to go down in price.”

“We spent last year trying to understand the marketplace. Advisors were saying, ‘My clients need to generate the most income today.’ As a secondary message, ‘They’ve put off their retirement and they need a recovery strategy,” Scheinerman said.

Aside from minor modifications that SunAmerica has made to existing products in the past year, Income Plus 6% and Income Builder 8% are the company’s first new annuity offerings since the financial crisis and the bailout of its parent company, AIG.

“We did about $1 billion last year, and we’re getting ready for a build-back this year,” he added, saying that AIG’s troubles have not hurt SunAmerica. “We have very high capital levels and there’s never been any question about our strength. People are comfortable selling our product. We distribute through all channels. The wirehouses are our main channel but we’re also strong in the bank channel.”

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

Tiny, Embattled Presidential Life Announces a New DIA

If you were a healthy 45-year-old male and someone offered you a lifetime income of $25,000 a year starting 20 years from now for $128,697—contingent on your survival—would you want to hear more? Or would you walk away?

How about a payment of just $86,816 at age 55 in exchange for $25,000 every year, starting at age 75?

Those are examples of the kinds of deals that tiny Nyack, NY-based insurer Presidential Life Corp. (rated B+ or “Good” by A.M. Best)—whose founder is currently trying to regain leadership of the company by storm—wants to make with its new Sentinel deferred income annuity.

The product is described as a revival of a product popularized between 1934 and 1936, when Americans opted for insurance contracts over stocks. It can be purchased by someone as young as 35, who at today’s prices could buy a $25,000 lifetime income starting in 2040 for $83,354, according to the company.

“We expect, younger individuals, ages 30 to 60 to purchase Sentinel annuities,” said Gary Mettler, CFP, a Presidential Life vice president. “Many individuals in this age category have more complicated lives that, by their nature, carry more ‘Black Swan’ type risks versus the typical deferred annuity purchaser who is usually over age 65, slowed down and retired.”

Initially offered only for non-qualified business, the policy is available in 14 states. Agents must receive training before they can sell the policy. Premiums can range from $10,000 to $500,000.

Owners can defer income from 5 to 30 years, depending on issue age, but not later than age 90. Income payments are guaranteed at the issue date. The income options include 5-, 10-, 15- and 20-year period certain; single and joint 100% survivor life with 5-, 10-, 15-, and 20-year period certain; and single and joint 100% survivor life only.

For period certain contracts, if the annuitant dies during the deferral period, the policy may return more or less than the premium cost to the beneficiary. If death occurs after income payments start, the beneficiary receives only the period certain portion; there is no lump sum.

Presidential Life has experienced managerial turbulence recently. The founder, Herb Kurz, has been trying to unseat Donald Barnes, his appointed successor and colleague for 15 years, from his position as CEO of Presidential Life, and to run the company again. RIJ asked Mettler to comment.

“At this time”—January 15, 2010—“the senior management issue finds the three major proxy advisory services in the country finding in favor of the current management team,” Mettler wrote in an e-mail.

“The lead independent board member, William Trust, has asked Herb to discontinue his attempt to re-instate himself as President and CEO. At this time, Herb has not responded to his request. This action should come to some conclusion within the next 30 days or so, if not sooner.

“However, Presidential remains one, if not the only, debt-free life insurance carriers in the United States and free of any federal government interference as the company never sought or accepted U.S. government relief monies.

“Presidential was not caught holding residential mortgage securities nor did the company ever engage in insuring others’ debt obligations. This is, as you know, unlike some other carriers.

“While 2009 has been a tough business year, and 2010 isn’t shaping up to be any better, Presidential Life remains self-reliant and that’s a lot more than what can be said about several A rated carriers.”

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

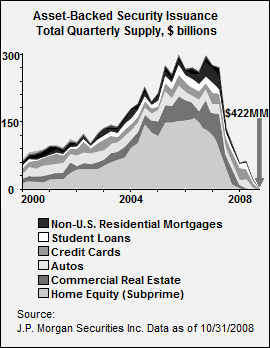

Asset Backed Security Issuance 2000-2008

New BoA/Merrill Ads Ask Prospects to ‘Fill-in-the-Blank’

It’s not about the money. Or is it?

Bank of America announced the debut of a $20 million marketing campaign whose tagline is pronounced “Help To Retire Blank” but appears in print as “help2retire______.” The campaign will run from January 25 to April 30, 2010.

The campaign encourages Americans to “fill in the blank” by identifying unwanted habits and to seek out a Merrill Lynch Wealth Management advisor for help focusing on what matters most in planning for retirement.

The tagline is meant to serve as a basis for ad themes like help2retire Guesswork, help2retire Confusion, help2retire The 6 AM Train, help2retire 9 to 5, and so forth. A team led by Hill Holliday developed the creative.

The campaign ties into Merrill Lynch Wealth Management’s “help2” campaign, launched last October. It was “designed to demonstrate a commitment to delivering personalized, insightful financial advice, along with a broad platform of financial solutions, to help clients pursue their financial goals,” the company said in a release.

The new campaign grew from a Merrill Lynch Affluent Insights Quarterly survey, released Jan. 14, which showed that 51% of retired respondents wish they’d focused more on their ‘life goals’ and less on ‘the numbers’ when preparing for retirement.

The new “help2retire______” campaign is scheduled for broadcast network and national cable programming, including on Bloomberg TV, The Golf Channel and CBS College Sports during the 2010 NCAA basketball regular season and conference championships, as well as across radio and “out-of-home” marketing channels.

Ads are scheduled for print and online editions of The Wall Street Journal, Barron’s, Fortune, Golf Magazine, Food & Wine, Kiplinger’s, The New York Times, The Economist, Investor’s Business Daily, Financial Planning, Investment News and others.

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

Sun Life, Miami Dolphins in Stadium Pact

Just in time for the 2010 Pro Bowl and Super Bowl, Sun Life Financial has purchased naming rights to the 23-year-old Miami Dolphins stadium in Miami Gardens, Florida, after itself. Boston-based Sun Life, a unit of Sun Life of Canada, will pay a reported $7.5 million a year for five years for the rights.

Sun Life Stadium is now the name of the home of the Miami Dolphins, the University of Miami Hurricanes, the Florida Marlins, and the FedEx Orange Bowl. It seats 76,500 people for football, 75,000 for soccer and up to 68,000 for baseball.

Since 1987, the structure has been called named Joe Robbie Stadium, Pro Player Park, Pro Player Stadium, Dolphins Stadium, Dolphin Stadium, and, briefly, Land Shark Stadium. The stadium has hosted four Super Bowls, two World Series, and three BCS National Championship games.

The stadium is 95% owned by New York billionaire real estate baron Stephen M. Ross, owner of the Miami Dolphins and founder, chairman and CEO of The Related Companies LLP (TRC), which built the $1.7 billion, 2.8 million square-foot Time Warner Center at Columbus Circle in Manhattan.

Sun Life will promote itself as the “Official Insurance Partner of the Miami Dolphins” as well as the “Official Wealth Management Services Partner of the Miami Dolphins.” The Sun Life Stadium logo will appear on printed promotional materials related to the stadium, all paper tickets, and stadium signage.

Priscilla Brown, head of U.S. marketing for Sun Life, said the company’s branding efforts include a campaign focusing on national print ads showcasing the company’s financial strength and on the launch of the company’s first-ever national television advertising, featuring Karl and Miles, the “Sun Life guys.”

Commercials depict the “Sun Life guys” traveling the country, working hard to get people to know the Sun Life name-including trying to convince KC and the Sunshine Band to change its name to “KC and the Sun Life Band.” Today’s announcement featured a special performance by KC and the Sunshine Band.

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

Obama Praises Annuities, In Principle

The administration sent a ripple through the annuity world and beyond on Monday when President Obama, Vice-president Biden and their Middle Class Task Force released a fact sheet claiming that, among other things, they are:

“Promoting the availability of annuities and other forms of guaranteed lifetime income, which transform savings into guaranteed future income, reducing the risks that retirees will outlive their savings or that their retirees’ living standards will be eroded by investment losses or inflation.”

His endorsement triggered a celebratory press release from the Insured Retirement Institute (formerly NAVA). San Diego conservative talk radio host Roger Hedgecock warned, however, that the Obama administration wants to nationalize Americans’ savings.

Most of the fact sheet was a reiteration of previously announced administration initiatives, including:

Automatic IRAs. The administration hopes to require employers who do not currently offer a retirement plan to enroll their employees in a direct-deposit IRA unless the employee opts out. Auto-IRA contributions will be voluntary and matched by the Savers Tax Credit for eligible families.

The administration is also helping 401(k) plans sponsors adopt auto-enrollment programs. New tax credits would help pay employer administrative costs. The smallest firms would be exempt.

Saver’s Credit. The administration’s proposed Saver’s Credit would match 50% of the first $1,000 of contributions by families earning up to $65,000 and provide a partial credit to families earning up to $85,000. The tax credit will be refundable, so that even families that pay no income tax will benefit.

Updating 401(k) Regulations. The administration said it would make 401(k) fees more visible, encourage plan sponsors to offer unbiased investment advice to participants, help workers avoid common financial errors and strengthen protections against conflicts of interest.

It also plans to require more disclosure of the risks of target-date fund to ensure that 401(k) plan sponsors and participants can better evaluate their suitability.

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

The Strongest Financial Brands Are…

Who has the strongest brands in the financial industry? According to the Cogent Research Investor Brandscape 2010 survey of affluent investors, the leading names are mostly household names: TIAA-CREF, Vanguard, Fidelity, Schwab, John Hancock, MetLife, The Hartford and American Funds (though not necessarily in that order).

But first place doesn’t necessarily mean great. Cogent’s survey showed low investor confidence in the financial services industry overall. Less than 40% of affluent investors polled were confident in their mutual fund provider, fund distributor or financial advisor.

| Fund Company | Rank | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2008 | 2006 | |

| Vanguard | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Fidelity Investments | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| American Funds | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| T. Rowe Price | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| TIAA-CREF | 5 | N/A | N/A |

| Franklin Templeton | 6 | 7 | 19 |

| Fidelity Advisor Funds | 7 | 6 | 11 |

| Oakmark | 8 | 29 | 31 |

| Morgan Stanley Inv. Advisors Funds | 9 | 8 | 9 |

| Schwab/LaudusFunds | 10 | 5 | 5 |

The national survey was conducted among 4,000 Americans over age 18 with household investments of $100,000 or more between last October 14 and November 4. The Boston-based group released an executive summary of the report, the third of its kind since 2006, late last week. The complete report is available for purchase.

Among 39 mutual fund providers considered, the three highest-rated brands were Vanguard, Fidelity and American Funds. Franklin Templeton rose to 6th in 2009 from 19th in 2006, and Oakmark vaulted to 8th last year from 31st in 2006.

The three highest-ranked brands among 20 fund distributors were Charles Schwab, Fidelity and Morgan Stanley Smith Barney. Edward Jones jumped from 14th place in 2006 to fourth in 2009.

Among six exchange-traded fund (ETF) providers considered, Vanguard was ranked highest in all performance criteria. Among 14 variable annuity issuers, TIAA-CREF earned the highest level of customer loyalty, followed by Ameriprise Financial and Allianz Life. (See RIJ’s Data Connection for top 10 VA issuers).

Risk-aversion rises

Aside from canvassing investors about specific providers of mutual funds, variable annuities and other products, the survey also registered trends in the risk appetite and financial product purchasing preferences among affluent investors, who represent only about 17.5% of U.S. households.

| Distributor | Rank | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2008 | 2006 | |

| Charles Schwab | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Fidelity Investments | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Morgan Stanley Smith Barney | 3 | N/A | N/A |

| Edward Jones | 4 | 8 | 14 |

| Merrill Lynch | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Raymond James | 6 | 5 | 10 |

| UBS | 7 | 9 | 2 |

| Vanguard | 8 | 6 | 6 |

| Wells Fargo Advisors/Wachovia Securities | 9 | N/A | N/A |

| Ameriprise | 10 | 11 | 12 |

Affluent investors have become more cautious since the 2008 financial crisis, the survey showed. Interest in guaranteed income or principal-protected products has grown while rates of ownership of mutual funds and participation in employer-sponsored retirement plans have fallen.

Ownership of annuities has risen four percentage points, to 34%, and allocation of assets to annuities rose 3.6 points, to 9.65% since 2006 years, the survey showed. Fixed annuities showed stronger increases than variable. Ownership of fixed indexed annuities remained at 6% of those surveyed.

“Interest in annuities is also on the rise across all age and wealth segments, particularly Silent Generation investors,” the report said. (The survey did not differentiate between deferred and immediate annuities.)

Among variable annuity issuers, all but TIAA-CREF “have more detractors than promoters” and “few VA brands achieve both high awareness and favorability, and firms that are less well known earn the highest impression ratings,” the survey showed. In 2009, loyalty toward VA providers was higher than in 2008, however.

These days, even the comfortable are worried, apparently. The authors of the report were struck by the growing risk-aversion of those surveyed, who had a mean asset level, excluding real estate, of $740,000.

This was true even for those between ages 28 and 44. “Gen-X has a similar risk profile to the Silent Generation, and we wonder if that mind-set will remain consistent,” said Tony Ferreira, managing director at Cogent Research.

“Even if they’re only 40 or 41 years old, they’re transitioning to lower risk tolerance products. And more are saying, ‘I want income but also some guarantees,’” he added. “We wonder if they have they been burnt so much in last ten years that they may never become more aggressive. That group is most likely to think they won’t get Social Security or that they’ll get reduced benefits or that they may have to wait longer or pay higher taxes on benefits.”

| Attitudes of Affluent Investors |

|---|

Source: Cogent Research Investor Brandscape, 2010. |

Affluent investors increased the share of assets they allocate to low risk investments to 34% in 2009 from 26% in 2008 and reduced their allocations to moderate and high risk assets by fo ur percentage points each, to 45% and 21%, respectively.

Ownership of mutual funds and participation rates in qualified plans are both down among affluent investors over the past three years, the report shows. Mutual fund ownership dropped to 78% in 2009 from 94% in 2006, a decline of 17%. Among fund owners, allocation to mutual funds has fallen to 44% from 53% since 2006.

Meredith Lloyd Rice, the project director of the Investor Brandscape study, pointed to several factors driving those trends: a shift to self-employment following last year’s widespread layoffs, migration to certificates of deposits and fixed annuities, and asset decumulation by those out of work or already retired.

Indeed, the Urban Institute reported this week that 8.2% of men between ages 55 and 64 are out of work and have been looking for work—up from only 2.7% in November 2007. About 1.3 million 62-year-olds claimed Social Security in 2009, a record number, partly because of the many 62-year-olds and partly because of unemployment.

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

Employer Match Strikes a Hot Debate

The topic of auto-enrollment in 401(k) plans and its potential impact on the employer matching contribution has sparked a scholarly rhubarb between the Urban Institute and the Employee Benefit Research Institute.

In December, researchers at the liberal Urban Institute reported evidence that the match at large firms with auto-enrollment is lower than at those without it. They warned that auto-enrollment, by lifting participation rates, could raise costs for employers and trigger cutbacks in the match or in other compensation.

“While auto-enrollment increases the number of workers participating in private pensions, our findings suggest it might also reduce the level of pension contributions,” wrote Barbara Butrica and Mauricio Soto in their report “Will Automatic Enrollment Reduce Employer Contributions to 401(k) Plans?.” RIJ reported their findings January 13, “Will “Auto-Enrollment” Kill the Employer Match?”

National newspapers publicized that story, prompting the EBRI, which is non-partisan but whose membership list is a Who’s Who of the retirement savings industry, to fire back with a statement refuting the Urban Institute’s assertion and questioning its data.

“Our recent analysis of plan-specific data shows that, at least among large 401(k) plans, plan sponsors actually increased the generosity of their contribution rates,” said Jack VanDerhei, EBRI research director and author of the analysis, in a statement released last week.

That was not the end of it. On Monday, Butrica e-mailed reporters a response to the EBRI report. It said that the EBRI’s data largely supported her findings, and reiterated that auto-enrollment—a key plank of the Pension Protection Act of 2006—could backfire.

“We think auto-enrollment is a good thing,” Butrica told RIJ. “But if employers do in fact lower their match rates to offset some of the higher costs, then auto-enrollment may have some unintended consequences.”

Vanderhei told RIJ he will release a full study of the impact of auto-enrollment and other pension innovations in a February EBRI Issue Brief.

If untold billions or even trillions of dollars were not at stake here—both in terms of Americans’ retirement savings and financial service company revenues—this point-counterpoint exercise would be purely academic. But billions are at stake.

This debate also comes at a time when academics have criticized the 401(k) system and when employers have shown a readiness to suspend matches during tough economic times. The financial industry is unsurprisingly sensitive to any news that might further erode consumer faith in defined contribution pensions as the primary path to retirement security.

EBRI’s rebuttal

The EBRI challenged the Urban Institute’s methodology and its inference that match rates are already about seven percentage points lower among large plan sponsors that use automatic enrollment than among those that don’t.

In rebuttal, EBRI cited its recent study showing that 42.5% of the defined benefit plan sponsors it surveyed had already increased or planned to increase their direct “first tier” match and/or their “second tier” non-matching contribution to their defined contribution plans.

EBRI also noted that “225 large defined contribution plans that had adopted automatic enrollment 401(k) plans by 2009, but did not have them in 2005.” The study showed that:

- The average 2009 first-tier match rate was 87.78%, up from 81.26% in 2005. [Note: An employer who matched an employee’s 3% deferral with a 3% contribution would have a 100% first-tier match rate.]

- The average effective match rate for 2009 was 4.32% of compensation, up from 4% in 2005.

- The average total employer contribution rate for 2009 was 6.35% of compensation, up from 5.46% in 2005.

But, while showing that match rates are higher at firms with auto-enrollment, EBRI also suggested that it wasn’t because they had adopted auto-enrollment. It was because they had recently closed or frozen their defined benefit plans.

The improvements in the match “were much higher for sponsors that had frozen/closed their defined benefit plans than for the overall average,” the report said. Those companies could offer higher 401(k) match rates because they were saving money on the conversion and because they wanted to ease the sting of losing the defined benefit plan, Vanderhei told RIJ.

Points of agreement

The Urban Institute researchers, whose study was published by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, don’t disagree with that assessment.

“We do not believe the EBRI results necessarily contradict our results. In fact, their findings with regard to DB plans are consistent with our conclusions. And, as we have shown, the first-tier match rates and EBRI effective match rates could increase with automatic enrollment, at the same time that our match rates decline,” Butrica wrote in her response to the EBRI assertions.

“Ultimately, the main point of our paper is that automatic enrollment is not free for employers and that profit-maximizing firms might look for ways to offset the higher costs of auto-enrollment. How they will do that is still up for debate, but our results suggest that some employers may reduce their match rates,” she added.

On Monday, Vanderhei conceded that he also believed that auto-enrollment could have unplanned and unwelcome consequences.

“I don’t disagree that there will be modifications seeking a long-run equilibrium [in the match]. Other papers have already said that auto-enrollment could cost employees in terms of match rates,” he told RIJ.

“My 2005 study showed that, all else being equal, auto-enrollment would work to the benefit of low-income participants but to the detriment of the highest quartile, because they may get anchored at the default rate,” he said.

“There’s no doubt that basic back-of-the-envelope math will show that, all else being equal, something will have to give. I took exception to the Urban Institute’s argument that this has already happened.

“The most important thing is that this is one input to a full study to be released [as an EBRI Issue Brief] in February looking at the overall impact of auto-enrollment on participants,” Vanderhei added. “It will cover much more than what happens to match rates, and will include auto-escalation and other things.”

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

Bank Annuity Fee Income Rose 12.9% in 3Qtr 2009

Bank holding companies (BHCs) earned $669 million in the third quarter of 2009, up 12.9% from the $593.1 million in second quarter and four percent higher than the $644.2 million earned in third quarter 2008, according to the Michael White-ABIA Bank Annuity Fee Income Report.

For the first three quarters of the year, bank holding companies earned $2.00 billion from the sale of annuities, a 2.5% increase over the $1.95 billion posted in the same period a year earlier, according to the “Michael White-ABIA Bank Annuity Fee Income Report”.

Wells Fargo & Company (CA), JPMorgan Chase & Co. (NY), and Bank of America Corporation (NC) led all bank holding companies in annuity commission income in the first three quarters of 2009. Banks with the highest year-over-year growth in annuity income were Bank of America, PNC Financial and Regions Financial Corp.

The report, compiled by Michael White Associates and sponsored byAmerican Bankers Insurance Association, is based on data from all 7,319 commercial and FDIC-supervised banks and 922 large top-tier BHCs operating on September 30, 2009.

Of the 922 BHCs, 388 (42.1%) sold annuities during the first three quarters of 2009. Their $2.00 billion in annuity commissions and fees constituted 13.5% of their total mutual fund and annuity income of $14.77 billion and 18.0% their insurance sales volume (annuity and insurance brokerage income) of $11.1 billion.

Of the 7,319 banks, 975 (13.3%) sold annuities, earning $705.5 million in commissions or 35.3% of the banking industry’s total annuity fee income. Overall bank annuity production was down 13.3% from $814.0 million in the first three quarters of 2008.

Seventy-one percent (71.4%) of BHCs with over $10 billion in assets earned third quarter year-to-date annuity commissions of $1.89 billion, constituting 94.6% of total annuity commissions reported. This was an increase of 3.5% from $1.82 billion in annuity fee income in the first three quarters of 2008.

Among this asset class of largest BHCs in the first three quarters, annuity commissions made up 16.1% of their total mutual fund and annuity income of $11.73 billion and 18.1% of their total insurance sales volume of $10.42 billion.

| Bank Holding Company | Annuity Fee Income ($ Millions) |

Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3Q YTD 2009 | 3Q YTD 2008 | ||

| Wells Fargo | $504.0 | 612.0 | -17.6% |

| JPMorgan Chase | 258.0 | 268.0 | -3.7 |

| Bank of America | 203.2 | 110.3 | 84.2 |

| Morgan Stanley | 168.0 | N/A | N/A |

| PNC Financial | 98.9 | 49.7 | 99.3 |

| Regions Financial Corp. | 71.2 | 21.2 | 235.7 |

| SunTrust Banks | 62.9 | 94.8 | -33.6 |

| U.S. Bancorp | 52.0 | 72.0 | ;”>-27.8 |

| Keycorp | 46.2 | 42.8 | 7.8 |

| HSBC North America | 36.4 | 50.1 | -27.3 |

| *3Q 2008 figure includes $86,000 for Wells Fargo & Company and $526,000 for Wachovia Corporation, which it acquired. SOURCE: Michael White-ABIA Bank Annuity Fee Income Report |

|||

BHCs with assets between $1 billion and $10 billion recorded a decrease of 12.2% in annuity fee income, declining from $104.2 million in the first three quarters of 2008 to $91.4 million in the first three quarters of 2009 and accounting for 3.0% of their mutual fund and annuity income of $3.03 billion. BHCs with $500 million to $1 billion in assets generated $16.7 million in annuity commissions in the first three quarters of 2009, down 18.0% from $20.4 million in the first three quarters of 2008. Only 34.7% of BHCs this size engaged in annuity sales activities, which was the lowest participation rate among all BHC asset classes. Among these BHCs, annuity commissions constituted the smallest proportion (13.0%) of total insurance sales volume of $129.0 million.

Among BHCs with assets between $1 billion and $10 billion, leaders included Stifel Financial Corp. (MO), Hancock Holding Company (MS), and NewAlliance Bancshares, Inc. (CT). Among BHCs with assets between $500 million and $1 billion, leaders were First Citizens Bancshares, Inc. (TN), CCB Financial Corporation (MO), and Codorus Valley Bancorp, Inc. (PA).

The smallest community banks, those with assets less than $500 million, were used as “proxies” for the smallest BHCs, which are not required to report annuity fee income. Leaders among bank proxies for small BHCs were Sturgis Bank & Trust Company (MI), The Juniata Valley Bank (PA) and FNB Bank, N.A. (PA).

Among the top 50 BHCs nationally in annuity concentration (i.e., annuity fee income as a percent of noninterest income), the median year-to-date Annuity Concentration Ratio was 6.1% in third quarter 2009. Among the top 50 small banks in annuity concentration that are serving as proxies for small BHCs, the median Annuity Concentration Ratio was 12.9% of noninterest income.

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

Heard On The Grapevine

The validity of “time-segmentation” methods of retirement income planning were the subject of a spirited, impromptu e-mail discussion last week among several members of the Retirement Income Industry Association.

The message chain, which sprang up spontaneously like a dust dervish in the desert, included commentary from well-known academics like Zvi Bodie, Larry Kotlikoff and Moshe Milevsky (at left), as well as David Macchia, purveyor of a time-segmentation tool, and others.

Time-segmentation, a core principle of certain “bucket” methods, divides a person’s retirement into periods of two to ten years each and assigns assets to each period, as a discrete source of income for that period. The later the investor plans to tap the assets for income, the riskier the assets can be.

The question for those in the e-chain was whether or not time-segmentation is a valid financial planning method and, more specifically, whether its apparent deference to the belief that equities pay off in the long run can be justified.

Let’s tune into the e-mail chain at the point where Macchia suggests that time-segmentation be debated at RIIA’s conference in Chicago on March 22-23, along with other methods that are scheduled for critical discussion.

Macchia (owner of Wealth2k, marketer of Income for Life Model): Given the rapid marketplace adoption, I feel strongly that time-segmentation must be added. The FPA recently released research indicating that 40% of advisors have adopted the concept, and we’ve seen numerous big players embrace [it], e.g. Nationwide, UBS, Bank of America, etc. Not to mention Wealth2k and Russell [Investments].

Charles Robinson (senior vice president, Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Co.): I would heartily second David’s suggestion.

Zvi Bodie (Boston University economist; author of Worry-Free Investing, Financial Times, 2008): What is the concept of time-segmentation? Does it refer to different age cohorts, accumulation vs. decumulation, or something else?

Michael Zwecher (former Merrill Lynch risk manager; author of Retirement Portfolios: Theory, Construction and Management, Wiley, 2010): It’s the idea that both you and Moshe have debunked repeatedly—essentially that you can ‘expect’ to grow your way out of the hole.

Bodie: Then why would RIIA want to support it?

Macchia: That is [an] unfair dismissal of a concept that has proven its value in more than two decades of real world experience. I’d recommend one speak with seasoned advisors whose experience shows that it takes more than an “optimal” academic framework to make retirement investing work in the field. We shouldn’t be waging a war over approaches; the debate is largely irrelevant. Thirty-two years of working with investors and financial advisors has taught me that once theory meets practice, theory often loses.

Zwecher: I’m not trying to be smug or argue that it is just a theoretical point. [Equities] may have paid off for long windows in the U.S. in the past. But, if you look at option prices today for any maturity, the capital markets are saying that I have no better than fair odds for beating the risk-free rate going forward.

Moshe Milevsky (York University finance professor; author of Are You a Stock or a Bond?, FT Press, 2008): I have yet to see any rigorous (or even non-rigorous, for that matter) article or paper that derives “time segmentation” as the output from any sort of optimization process. I wish there was.

In fact, I have actually been thinking about this carefully, and I can’t locate any rational preference function that would lead to this type of strategy. Perhaps, prospect theory together with a mental accounting type argument might work, but that is mixing positive and normative economics.

In other words, just because you can explain observed behavior with a distorted loss-function, doesn’t mean it should be advocated for the masses. Of course, if the justification for a strategy or product is that practitioners have been using it for decades and have been “quite happy” with the outcome, then we have bigger problems.

Macchia: To be clear, I’m not advocating anything for the masses—including time-segmentation. I do believe that time-segmentation can be appropriately employed for some investors, especially when it is combined with a floor of guaranteed lifetime income. There are many approaches to this issue, and we can’t know which among these will yield the best results in practice.

Francois Gadenne (chairman of RIIA): I wonder if we are all seeing the same thing when we read the words: time-segmentation. How many of us see time segmentation to mean buckets of risky assets? How many of us see it to mean a mix of buckets, including precautionary reserves, longevity (risk pooling), floors (risk transfers) and risky assets?

Milevsky: I don’t think “buckets” diversify risk. I provided a counter-example in the attached article (“Spending Buckets and Financial Placebos”).

Chris Raham (leader of Ernst & Young’s Retirement Income Practice): I think it depends on what you put in the buckets.

Laurence Kotlikoff (creator of ESPlanner software; co-author of Spend ‘til The End, Simon & Schuster, 2008): I looked at David’s movie about his product and it’s possible that there is less disagreement here than meets the e-mail eye. My sense, based on the video, is that the product puts people into safer securities for the short term and less safe securities for the long term (at least as Zvi, Michael, Moshe, and I would describe them). There are three ‘buts’ here, however.

‘But’ number one is that if households are borrowing-constrained [unable to borrow] because they hav e short-term saving goals, like getting together a down payment for a house or paying tuition, they are, in effect, facing sure liabilities that need to be matched with safe assets of equal maturity. This may be what David has in mind in encouraging safe short-term investments.

Second, I took David’s product to be trying to provide a floor to the household’s living standard via its focus on inflation-projected bonds or annuities. This seems reconcilable with habit formation—with the fact that people do not want their living standard to decline.

Third, if the households David has in mind are borrowing-constrained, they may, indeed, optimally allocate more to risky investments (i.e., stocks) over time because their short-run liquidity constraints make them effectively highly risk-averse in the short run, but less risk averse in the long-term.

For example, if I have $100,000 and absolutely need $101,000 to buy a house in a year and have no other assets, I’m going to invest in safe one-percent Treasury bills. But in ten years, once I’ve accumulated enough wealth to bother thinking about investing, I may well opt to start investing in equities.

This isn’t to say that equities are safe in the long run, but that a person’s long-run risk aversion can differ from his or her short-run risk aversion. I don’t at all like suggesting that equities are safer the longer you hold them, because I don’t see a scientific basis for that statement. But I do find it reasonable to say that many risk-averse households may find equities a more attractive way to invest for the long-term than the short-term.

Keith Piken (managing director, Bank of America): It’s a dialogue worth having and I know our advisors and their clients continue to struggle in search of the “right” answer.

Kerry Pechter (RIJ editor; author of Annuities for Dummies, Wiley, 2008): I recently asked Meir Statman [the behavioral economist at Santa Clara University] if he thought time-segmentation was “natural.” Here’s his reply:

“Portfolio bucketing is the new version of the old tin cans or envelopes system. How the brain developed is speculative, but we need not jump very far to see that we prefer to solve easy problems rather than difficult ones.

“We simplify a big problem, like budgeting for a household or constructing a portfolio, by breaking it into smaller problems. First we divide them into envelopes or buckets, and then we spend from them. Compare arranging the documents and receipts you need at tax time in one big heap or in an accordion folder by topic.

“Buckets also help because they link money to goals, and an overall portfolio does not. Last but very much not least, buckets help self-control. Putting your hand into the electricity bill envelope for cigarette money makes you feel guilty, perhaps stopping you. Same for dipping into your child’s college fund to buy a shiny car.”

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

Fresh Rumors About MetLife and AIG Reported

American International Group Inc. may be trying to sell American Life Insurance Company (Alico) to MetLife Inc. for more than $14 billion, National Underwriter reported.

Rumors that MetLife might be interested in buying some of the life operations of AIG have been floating around for months, but fresh rumors have surfaced in the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times’ DealBook.

Selling Alico could help AIG repay the federal government for the aid provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and the U.S. Treasury Department. Buying Alico could help MetLife continue to expand outside the United States, said Clark Troy, a senior life insurance industry analyst at Aite Group LLC, Boston.

“A MetLife deal for Alico at a $14 billion valuation is clearly a good deal for the U.S. taxpayer,” Clark said. “Aside from supporting the $9 billion valuation for Alico, it bodes well for a future [public stock offering] or acquisition of AIG. Any profit that accrues to legacy AIG strengthens its balance sheet and increases the likelihood that it will be able to make the government whole.”

MetLife, meanwhile, could use the deal to strengthen its position in Asia, Clark says. MetLife is the leader in Japan’s variable annuity market, and a MetLife joint venture ranks second in Japan’s non-life market. Alico has a strong position in Japan’s life market, Clark said.

© 2010 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

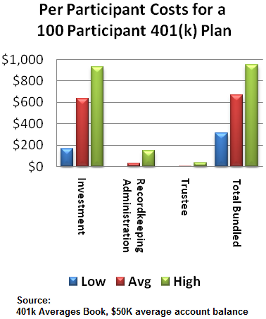

Per Participant Costs for a 100 Participant 401(k) Plan