Overweight Baby Boomers are digging their graves with their spoons. Skinny Boomers are obsessed with exercise and antioxidants. These counter-trends make life confusing for the experts who just want to know exactly when the average retiree will die.

On Sept. 25 and 26, a bunch of those experts convened on the 50th floor of the JP Morgan Building, where brilliant silk-screens of zoo animals by Andy Warhol adorn the interior walls and the glass outer walls reveal a 360-degree sky-view of New York City.

Fifty or so economists, actuaries, bankers, insurance executives and aging experts had traveled from as far as Taiwan and Germany to attend Longevity 5, the fifth in a series of international meetings, and to hash out responses to the global aging trend.

For many of them, global aging is as big a threat as global warming. Instead of rising sea levels and desertification, they foresee a tide of longevity risk that could bankrupt the social insurance programs, pension funds and annuity issuers whose obligations are linked to the length of people’s lives.

“Economists have not really understood this risk. Policymakers are not yet engaged,” said David Blake of the Pension Institute at the Cass Business School in London and the chairman of the conference. “This is a real, underestimated, slow-burning risk.”

Or, as Joseph Coughlin, the bow-tied director of the MIT Age Lab put it, “There are going to be a lot of old people with attitudes and expectations.

On the other side of the bet, financiers in suits are circling. JP Morgan Chase and Goldman Sachs have built longevity indices. A few pension funds have used swaps to off-load longevity risk. Life settlement companies are buying up life insurance policies and selling “death bonds.” But, relatively speaking, the response to the aging problem is in its infancy.

The case for longevity bonds

The dilemma boils down to this: who will bear the financial risk that billions of people might live too long?

In Finland and Germany, governments are pushing some of the longevity risk of their social insurance programs back onto individual participants by adjusting benefit levels to fit changing mortality rates and market performance.

Alternately, pension funds are looking to share their risks with investment banks. Last July, the Devonport Royal Dockyard pension fund became the first UK pension fund to enter into a longevity swap, in a deal with Credit Suisse.

Investment banks may buy the risk, securitize it, and sell it in the capital markets to investors who are looking for an asset class uncorrelated with stocks or bonds. Or a government could issue ultra-long-dated “longevity bonds” and spread the risk across generations.

A majority of those at the Longevity 5 conference seemed to favor the idea of the U.S. government issuing 50-year longevity bonds, pegged to a longevity index, that would mitigate longevity risk the way Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities mitigate inflation risk.

Guy Coughlan, managing director and global head of JP Morgan’s LifeMetrics and Pension Solutions business, said the U.S. government has a “responsibility” to issue longevity bonds because it encouraged the transition from defined benefit to defined contribution retirement plans and dumped longevity risk on the plans and participants.

“There’s a social need to pick up the risk borne by corporations,” Coughlan said. Longevity bonds “would help create an orderly market for annuities.” Peter Blake agreed, saying the “U.S. government has obligated companies to honor their pension liabilities, and now it says it has nothing to do with the government.”

The U.S. wouldn’t have to issue enough longevity bonds to pick up all of the risk, said Tom Boardman of Prudential plc, which issues about one-eighth of all individual income annuities in the world. “Private industry can handle 85% of the risk,” he said. “We’re just looking for protection of the tail.”

Coal mine canaries

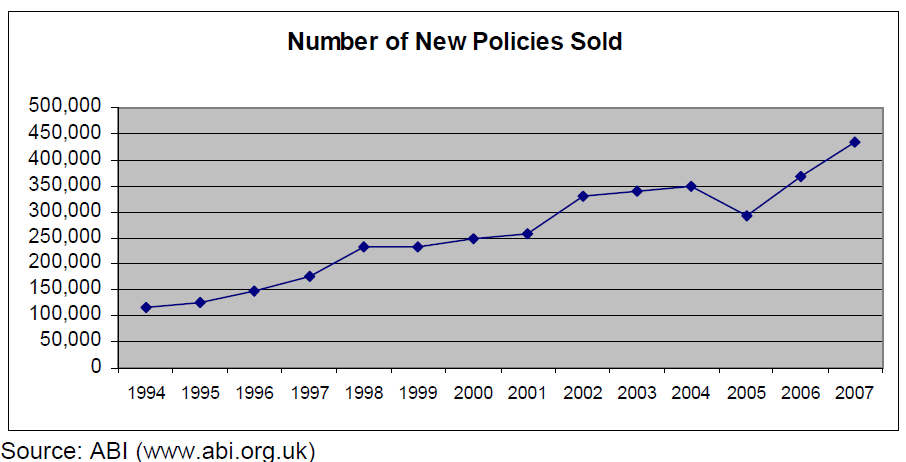

The British are apparently the canaries in the longevity coal mine. Under recent pension reforms, those in the U.K. have to annuitize their tax-deferred savings by age 75, and millions buy life annuities at retirement. The British now buy about half of all life annuities in the world each year, making themselves a test case for coping with longevity risk.

The pipeline into annuities in Britain will get even bigger in 2012, when workers who don’t now have workplace pensions will be auto-enrolled in a defined contribution program to which they, their employers, and the government (through tax breaks) will contribute. That could eventually double the demand for annuities, to £30 billion a year.

“For a small country, those are significant numbers,” said Boardman. “Insurance companies don’t have the capacity to take on that kind of risk. But the capital markets do.”

The same capacity problem could occur in the U.S.-if large numbers of Americans were inclined to buy life annuities with their trillions of dollars in defined contribution savings. Theory dictates that that should happen-but it isn’t, said James Poterba, the MIT economics and president of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

“Our models tell us that people will see a role for annuities,” Poterba said. “But there’s very little activity in the annuity markets. That’s the so-called annuity puzzle, which has attracted a large percentage of the research community.”

Insurance companies might be able to offer more attractively priced annuities to U.S. retirees if they could lay off their longevity risk in the capital markets, he suggested. But he believes that, even with better pricing, selling individual annuities will “still be an uphill battle.” The existence of a public annuity-Social Security-probably crowds out some of the demand for private annuities, he said.

It all adds up to a gloomy picture-almost as gloomy as global warming. If there’s a silver lining, Poterba told some of the world’s top pension wonks, it’s that at least the 2008-2009 financial crisis gave us a warning to reform our retirement systems before it’s too late. By 2025, he said, much more savings will be at stake, and a similar crash would make last year’s $500 billion drop in retirement fund assets look mild.

© 2009 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

In 2008, the Association of British Insurers data indicates, over 450,000 pensions annuities were written, with an average “pensions pot” or retirement account balance of about £25,000 ($40,000). The median value was only about £15,000 ($24,000), with 75% of cases related to pensions pots worth less than £30,000 ($48,000). A pensions pot of £15,000 would generate a level income of perhaps £1000 ($1600) a year for a male aged 65, with no spousal entitlement.

In 2008, the Association of British Insurers data indicates, over 450,000 pensions annuities were written, with an average “pensions pot” or retirement account balance of about £25,000 ($40,000). The median value was only about £15,000 ($24,000), with 75% of cases related to pensions pots worth less than £30,000 ($48,000). A pensions pot of £15,000 would generate a level income of perhaps £1000 ($1600) a year for a male aged 65, with no spousal entitlement. Enhanced annuities, which accelerate payments for contract owners who have health issues that reduce their life expectancies, have been popular among retirees in the U.K. They don’t yet sell as well as standard income annuities, but their market share is 16% and growing. In the U.S., these products are known as “impaired risk” or “medically underwritten” annuities.

Enhanced annuities, which accelerate payments for contract owners who have health issues that reduce their life expectancies, have been popular among retirees in the U.K. They don’t yet sell as well as standard income annuities, but their market share is 16% and growing. In the U.S., these products are known as “impaired risk” or “medically underwritten” annuities.

“Some people say it doesn’t work, that you can’t reach young people this way, that’s it’s still too formal,” he said. “We just launched the book, and we are this week still sending it to people under 35 as part of a packet with other information. So we don’t yet have measurements of the results.”

“Some people say it doesn’t work, that you can’t reach young people this way, that’s it’s still too formal,” he said. “We just launched the book, and we are this week still sending it to people under 35 as part of a packet with other information. So we don’t yet have measurements of the results.”