And the winners are. . . MassMutual, Fidelity Investments, and Lincoln Financial Group.

Earlier this year, Phoenix Marketing International, a Rhinebeck, NY research firm, asked investors to review 27 print and TV ads and grade them from one to seven on each of 25 attributes, such as persuasiveness, creativity, and ability to spark action.

The results of the twice-a-year syndicated Retirement Services Study, in which as many as 70 companies participate, were released this month. Companies subscribe to the study and receive a detailed assessment of brand awareness and advertising awareness across the financial services industry.

The study is based on feedback from some 700 people ages 35 to 64, half affluent and half non-affluent, who are customers of at least one of the ad sponsors. The affluent participants have a household income of at least $100,000 and have non-retirement investments of $100,000 or more.

“Once a year, we do a ‘best practices’ overview, and consider all the advertising that we assessed during the year,” said Phoenix Product Manager Kristina Terzieva, who managed the survey. “We pick out the strongest ads and identify their commonalities, themes and messaging.

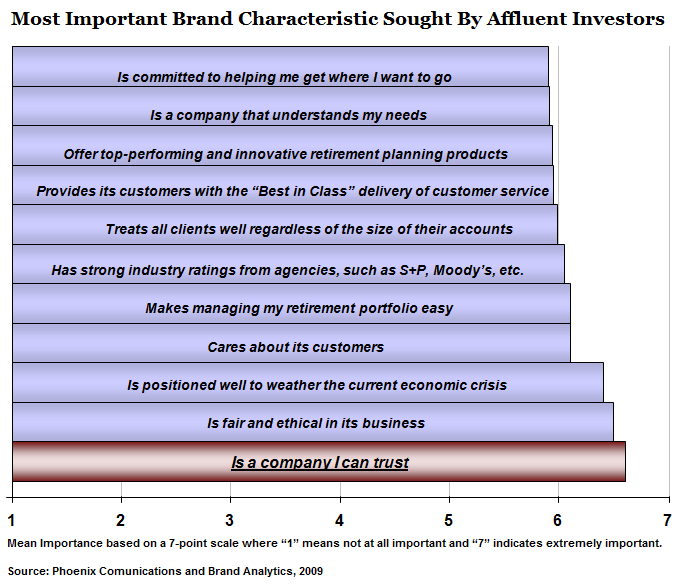

“The issue of trust is the most important, as well as showing something different, and focusing on the benefits without overwhelming them with information,” Terzieva said. “The company should answer the question, ‘Why should I invest with you?’”

Rainy day woman

In MassMutual’s print ad, a woman with short dark hair gazes through a rain-streaked window at a blurred backyard landscape beneath the headline, “WHAT IS THE SIGN OF A GOOD DECISION? It’s feeling secure, even when times are stormy.” Below the image a block of copy (not shown here) pitched the MassMutual value proposition.

The ad drew a wide range of responses. Many reviewers said it “spoke to them.” Some said it left them cold.

But the positive comments outnumbered the negative ones enough to make the ad the most popular print of all those reviewed. “I feel exactly like the woman looking out at the rain,” said one reviewer, who gave the ad “6” out of seven points. “Sometimes I am sad about our economy.”

Others felt reassured by the facts listed in the paragraph of text below the image. It emphasized MassMutual’s 157-year history, its $8.5 billion cash cushion, its steady delivery of dividends to policyholders, and its independence from “Wall Street.”

“There’s a lot of understandable consumer skepticism out there. They don’t want claims, they want facts,” said Vic Lipman, assistant vice president for branding and advertising at MassMutual. The ad was created by the Boston-based Mullen agency. It ran as full-pages in the New York Times and Wall Street Journal last February and March.

The ad was part of the insurer’s “Good Decisions” campaign, which MassMutual started researching in the spring of 2008. “The notion of ‘good decisions’ kept coming up in our research,” Lipman added. “It resonated with both consumers and professionals. People want help making good decisions. Later, as the financial crisis unfolded, we found that it was appropriate for that environment too.”

MassMutual career agents have been using reprints of the ad for sales and recruiting with great success, Lipman said. “We’re planning on staying the course with the Good Decisions campaign,” he said. “It has a lot of legs and we want to use it for the foreseeable future.”

First-class treatment

“We’ve identified four specific themes running through the ads,” Terzieva said. The most important is credibility. Then there must be a cognitive connection. The ad should resonate with the reader, and be informative, clear and believable. Third, there’s personal relevance.

| Companies Participating in Phoenix Retirement Ad Surveys |

| Phoenix determines which companies are currently advertising and selects up to 30 ads for each semi-annual study. The advertisers listed below are included: |

| ADP |

Aetna |

AIG |

AIM |

| Alliance Bernstein |

Allianz |

American Century |

American Funds |

| Ameriprise |

AXA |

Bank of America |

Bankers Life & Casualty |

| Charles Schwab |

Berkshire Life (Guardian) |

C N A |

Colonial Life & Accident |

| Columbia Funds |

Commonwealth Financial |

Davis-Selected Advisors |

Eaton Vance |

| Fidelity/Fidelity Advisors |

Franklin Templeton |

Genworth Financial |

Goldman Sachs |

| Guardian |

The Hartford |

ING |

Invesco AIM |

| Jackson National |

Janus |

John Hancock |

Lincoln Benefit |

| Lincoln Financial |

Lord Abbett |

LPL Financial Services |

Mass Mutual |

| MedAmerica |

Merrill Lynch |

MetLife |

MFS |

| Mutual of Omaha |

Nationwide |

Northwestern Mutual |

NY Life |

| Oppenheimer |

Pacific Life |

Paychex |

PIMCO |

| Pioneer |

The Principal |

Prudential |

Putnam |

| Raymond James |

Scudder |

Smith Barney |

State Farm |

| Standard Insurance |

Sun Life |

TD Ameritrade |

TransAmerica |

| Travelers |

T.Rowe Price |

UnumProvident |

US Trust/Bank of America |

| USAA |

Wachovia/Wachovia Securities |

Waddell+Reed |

Van Kampen |

| Vanguard |

Zurich Kemper |

|

|

“A good example of that is one of the Lincoln Financial ‘FutureSelf’ TV ads, where the individual meets his older self on an airplane,” she said, referring to 15-second spot in which a business traveler in the window seat of an airliner strikes up a conversation with a greyer, craggier version of himself, 15 years hence.

The older man compliments his younger self for saving money by flying coach-class. Soon the older man leaves, explaining that he’s returning to his seat in the first-class section. “You can afford it now,” he says.

“It was inspirational,” said Terzieva. “It touches on the needs of the end user, and it’s a little more emotional and touching than others.”

But the Lincoln ad, while highly affecting, wasn’t considered as effective as one of Fidelity Investments ‘green line’ TV ads. In it, an investor chats with his advisor in a Fidelity branch office. As the investor leaves, a green carpet unfurls on the sidewalk ahead of him. But when he steps off the green path to yearn at a vintage AC Cobra roadster through a showroom window, the advisor sets him back on the straight and narrow.

“The fourth theme is the creative,” Terzieva said. “Does the ad break through the clutter and create buzz?” Examples of that would be any of the E*Trade ads in which a verbally precocious toddler in a high chair explains how easy day-trading can be. But the most clever ads don’t necessarily get the highest effectiveness ratings, Terzieva said.

Of the major financial services firms, Charles Schwab, Fidelity, State Farm, T. Rowe Price, and Vanguard most impress investors, in terms of solid reputation, according to Phoenix. Perhaps not coincidentally, four of those five firms market direct to consumers. MetLife, New York Life, and The Hartford also had high-ranking ads in the survey.

© 2009 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.