Over the past 10 years, a new and vigorous business model has gone viral in much of the once-stodgy life insurance and annuity industry. The model encompasses three types of enterprises, all owned, in many cases, by the same financial services company, private equity firm, or holding company.

The academics, regulators, and consultants who have studied the development of this business model have a new name for it: a “liability origination” platform or “private debt origination” platform. “Liability origination” refers to the art of lending profitably to below-investment grade borrowers without getting burned.

“Asset managers, particularly private equity (PE) firms, are using the new triangular organizational structure to scale up their private debt businesses,” said a recent report by three Federal Reserve economists.

“These institutions create their organizations by acquiring a suitable existing life insurance company and then establishing an offshore captive reinsurer… Starting from virtually nothing in 2008, PE firms now control roughly 8% of U.S. life insurance industry general account assets, equivalent to more than $350 billion.”

Recent news about deal-making in the life insurance industry offers examples of this trend, though usually with little context: Voya’s sale of annuity blocks to a reinsurer, KKR’s intended acquisition of Global Atlantic Financial, and the transfer of $27.4 billion in fixed annuity assets from Jackson National to Athene. MetLife’s decision to spin off its annuity businesses as Brighthouse Financial, and Prudential Global Investment Management’s pursuit of defined benefit pension assets in the U.S. and U.K., are part of this trend as well.

In this article, the third in a series, we’ll try to describe the complex liability origination platform model. The forces driving its development—the Federal Reserve’s low interest rate policy and a decline in lending by banks to high-risk corporate borrowers—are a topic for another day. Here we’ll focus on the new model, and how it turns baby boomer savings into fuel for complex loans.

Three-part engine

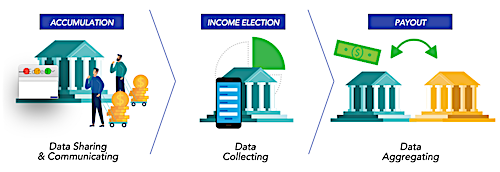

The three most essential components of liability origination, usually under a single corporate umbrella, are:

- One (or a group of) life insurance subsidiaries that acquire money by selling fixed annuities and fixed indexed annuities (FIAs), buying blocks of existing fixed annuity assets and liabilities; pursuing “pension risk transfer” deals; or borrowing funds from capital markets using unconventional debt-like instruments

- An asset manager that, more so than a conventional life insurer investment department, knows how to originate and/or buy risky corporate loans and commercial mortgages, and bundle them into asset-backed securities, which are subsequently held by their affiliated life insurers

- A Bermuda-based “reinsurer,” typically owned by the same holding company as the life insurers and asset manager, that allows for capital arbitrage between regulatory jurisdictions; life insurers can transfer (reinsure) blocks of fixed annuity business and reduce the amount of capital required to back the liabilities

Last February, two research reports on this model appeared. In “Capturing the Illiquidity Premium,” three analysts at the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, DC wrote:

A large number of life insurers and corporations are discarding blocks of capital-intensive long-term liabilities, such as annuities and defined benefit plans, as they struggle to find long-term assets with yields high enough to fund those liabilities. Some of the largest U.S. life insurers and private equity firms are exploiting the dislocation in the annuity markets.

These institutions redeploy the relatively stable source of long-term annuity capital to capture the illiquidity premium created by banks exiting corporate lending. Within ten years, the U.S. life insurance industry has grown into one of the largest private debt investor in the world.

In a separate report, “Liability Platform Developments,” Scott Hawkins, the insurance research director at Conning, wrote:

Since their emergence in the early 2000s, specialist insurers and reinsurers have been formed that focus on acquiring and managing insurance liabilities. By the end of 2019, there were 32 liability platforms domiciled in Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, the EU, and the United States, with the majority of the formations occurring in 2014 and later.

These platforms [fall] into two broad categories. Liability consolidation platforms, such as Monument Re, Somerset Re, or Viridium, acquire closed blocks of business from insurers who off-loaded these liabilities as they focus on their core business. These acquisitions can be through reinsurance, traditional Mergers & Acquisitions, or Part VII transfers. Liability origination platforms, such as Athene and F&G, go beyond liability consolidation and create new liabilities by selling new business.

In some cases, such as AIG and its formation of Fortitude Re, it was the desire to spin out closed blocks of business [in-force contracts] that led to the creation of a liability platform. For others, Athene being the most noticeable, the ability to have access to permanent capital led to its development of many new liability platforms. [The platforms] have focused on annuities because they have lower costs of capital than life insurance. Lower capital requirements enable investors to support more liabilities [i.e. loans], potentially generating higher profits as a result.

The humble indexed annuity

The key to these multi-billion dollar deals is, ironically, the humble individual retail fixed annuity—especially its popular variant, the fixed indexed annuity, or FIA. Simple fixed annuities are like certificates of deposit. FIAs are similar, but with a side-bet on the movement of an equity index. All offer tax-deferred growth with a guarantee against loss if held to maturity.

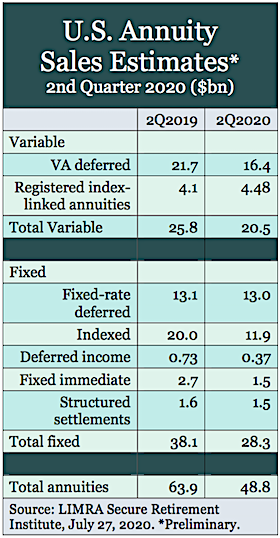

Fifteen years ago, FIAs were considered “Wild West” insurance products—sold by highly incentivized independent agents to older people who didn’t understand what they were buying. The pioneer, and still the top retailer, is Allianz Life. But, since the financial crisis, more insurers and distributors have built and distributed them. The assets backing in-force fixed annuities and FIAs are now worth close to $1 trillion, according to LIMRA Secure Retirement Institute.

Their stability makes them attractive sources of investable funds for private equity firms. Fixed annuities seek higher yields through longer holding periods. Purchasers invest for between three and 10 years. These “long-dated liabilities” give private equity firms and their affiliated life insurers a stable source of financing for long-term lending.

Most importantly, there’s virtually no risk that individual contract owners will suddenly want their money back until the end of the term. Athene, the most prominent private equity-owned life insurer after Allianz Life, has been the second biggest seller of FIAs in recent years.

“A life insurance company’s balance sheet is a savings mediation vehicle, and the company deploys that savings as credit into economy. Unlike a bank, a life insurer has stable long-term funding—not the short-term demands of a bank. When you have the advantage of long-time horizon, you can get creative in areas of lending where life insurers traditionally haven’t played,” Matt Armas, a portfolio manager at Goldman Sachs Asset Management, explained to RIJ in an interview.

CLOs encounters

If private equity firms find blocks of fixed annuity contracts so attractive, why do so many traditional life insurers want to get rid of theirs? The answer is falling interest rates. As rates go down, life insurers have difficulty earning enough on their new investments to cover the promises they made to fixed annuity purchasers when rates were higher.

Asset managers and private-equity firms like Guggenheim, Apollo, Goldman Sachs Asset Management, Blackstone and others were able to buy those contracts—which were tying up precious capital on the insurers’ balance sheets—at discounts. They believe they can invest the assets for higher returns than the original issuers could.

What’s their secret? A talent for “liability origination.” The asset managers at private equity-owned life insurers don’t simply buy highly rated corporate bonds off-the-rack. They buy lower-rated corporate bonds and, through the dark art of asset securitization, custom-tailor them into the relatively high-yield debt they and their customers (including their affiliated life insurers and private investors) want to own.

Among those securitizations are collateralized loan obligations or CLOs. In their latest incarnation, they are bundles of high-risk corporate loans divided (as all securitizations are) into tranches of varying risk. Owners of senior tranches get paid first, which means they’re most likely to get paid and that their tranches carry investment-grade ratings.

Senior tranches of CLOs pay higher returns than similarly rated loans. One reason for the premium, the authors of “Capturing the Illiquidity Premium” wrote, because of their illiquidity. It’s time-consuming to trade them, precisely because they are complicated, specialized and difficult for buyers to evaluate. This makes them riskier, and therefore higher yielding.

A recent white paper from Guggenheim, the global private equity firm that owns Delaware Life, defines CLOs as:

“…a type of structured credit. CLOs purchase a diverse pool of senior secured bank loans made to businesses that are rated below investment grade. The bulk of CLOs’ underlying collateral pool is comprised of first-lien senior-secured bank loans, which rank first in priority of payment in the borrower’s capital structure in the event of bankruptcy, ahead of unsecured debt. In addition to first lien bank loans, the underlying CLO portfolio may include a small allowance for second lien and unsecured debt.”

For life insurers looking for securitized debt to buy, CLOs have helped replace residential mortgage backed securities (RMBS), whose supply dropped after the 2008 financial crisis. According to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), “Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs) continue to be a growing asset class for U.S. insurers; exposure increased to about $158 billion at year-end 2019, having increased 17.5% from about $130 billion at year-end 2018.”

“The strategy is securitization, but the skill is in origination,” said Michael Siegel, a managing director at Goldman Sachs Asset Management, in an interview. “First, you’re cutting out the middleman. When I did private placement for traditional insurers, we had to look for investment-grade borrowers, focus on agent-led deals that were arranged by investment banks.”

Not to be left behind, however, large traditional life insurers have been buying or building their own sophisticated asset management teams. “The traditional life insurers are building out their infrastructures [for private debt origination], but the private equity firms were way ahead of them,” Siegel told RIJ.

Bermuda: Third leg of the triangle

The third and most mysterious aspect of the liability platforms involves captive offshore reinsurers. “Captive” means that the U.S. life insurer owns its own reinsurer. “Offshore” usually means that the reinsurer is domiciled in Bermuda, which uses a different accounting standard than the U.S. does.

U.S. life insurers can isolate blocks of fixed annuity assets and liabilities, move them to their own reinsurers in Bermuda, and get a credit—usually in the form of a line of credit from a bank—for the reduction in capital requirement. This credit “frees up,” for other asset purchases, part of the capital that, under U.S. statutory accounting rules, was dedicated to supporting the annuity guarantees.

Have the private equity companies’ ventures into the life insurance industry been healthy or not? The private equity people would say that they’ve done a lot of good by infusing capital into existing life insurers after the financial crisis, taking burdensome business off their books, and ensured that all of their policyholders get paid in full and on time.

“The private equity firms have brought about $30 billion in fresh capital into the life insurance industry, which was looking to transfer the risks of their older blocks of business. That’s a healthy evolution for the industry,” Goldman Sachs’ Armas told RIJ. (Goldman Sachs got into the insurance business as early as 2004, and eventually created Global Atlantic Financial Group in 2013, which owns a life insurer. KKR, the private equity firm, is in the process of buying Global Atlantic from Goldman Sachs.)

“One point about this new business model is that, with a growing number of retirees looking to save for retirement and turn accumulated assets into retirement income, the new capital from these players is increasing the ability of insurers to write more annuities,” said Conning’s Hawkins.

In “Capturing the Illiquidity Premium,” the authors expressed some concern about the risks embedded in the CLO tranches that life insurers are holding–which may include tranches of “combo notes.” These are CLOs built from the riskiest tranches of other CLOs.

“By holding the riskiest portions of the CLOs issued by their affiliates as well as a rapidly growing portfolio of commercial real estate loans, life insurers are vulnerable to a downturn in the credit cycle. For example, a widespread decline in the value of the loans backing the CLOs could directly wipe out the equity held by the affiliated life insurers,” they wrote.

The NAIC has issued several reports on CLOs, and has periodically assessed their riskiness in life insurer general account portfolios. “CLOs are a focus of regulatory concern, particularly as the underlying bank loans are experiencing negative rating actions as a result of the impact on certain industries from the economic disruption caused by COVID-19,” one recent report said.

But the NAIC concluded in the same report that “Since U.S. insurer exposure to CLOs is relatively small, at about 2% of total cash and invested assets as of year-end 2019, and the vast bulk of these investments are rated single A or above, we do not believe that the CLO asset class currently presents a risk to the industry as a whole.”

One life insurance industry stakeholder, who asked not to be identified by name, said that they and their peers are concerned about life insurers who own fixed annuity assets and liabilities and operate liability platforms but don’t sell annuities to the public and may have no incentive to serve their existing policyholders properly.

“Industry representatives are especially concerned about the run-off blocks of business, where the insurance company isn’t engaged in the current sale of insurance and doesn’t have the same concerns about reputation,” the source told RIJ. “That whole run-off area has been booming over last decade, and the PE companies are big players in it. Some are responsible; but their incentives are not as aligned with policyholder as someone writing business.”

© 2020 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.