UK pensions race to de-risk before Brexit

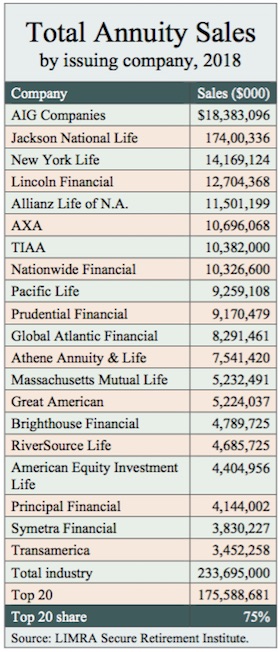

Prudential Retirement, a unit of Prudential Financial, Inc., has concluded about $2.6 billion in previously undisclosed longevity reinsurance contracts in the U.K. pension risk transfer market so far in 2019. As part of these transactions, Prudential Retirement is assuming the longevity risks of approximately 16,000 pensioners.

Many UK pensions are seeking to close agreements prior to the original March 29 Brexit deadline, a Prudential release said. But the recent extension of the Brexit deadline to late October, pensions have an unexpected window to move forward and de-risk.

Demand for de-risking solutions has also been driven by the robust funded status of U.K. schemes, which have improved markedly since 2016, the release said. The funding level of the average U.K. pension scheme stood at 100.1% on March 29.

“Pension schemes that can afford to de-risk have raced forward in the opening months of 2019, taking advantage of the window before Brexit to reduce their risks and lock in gains,” said Amy Kessler, head of longevity reinsurance at Prudential Financial, in the release. “Brexit brings increasing levels of uncertainty that could wash away recent market gains and funding improvements, putting de-risking out of reach for those with lower hedge ratios. But with funding at the highest levels in a decade, pensions are de-risking at an unprecedented pace.”

“Another impetus to de-risk is the notable decline in U.K. mortality rates during the last 10 months,” said Christian Ercole, vice president at Prudential Financial. “The resulting level of market activity favors insurers and reinsurers who have invested in their pricing and analytics teams, and it also favors pension funds that come prepared with credible and complete data.”

Prudential said it has completed more than $60 billion in international reinsurance transactions since 2011, including the largest on record, a $27.7 billion transaction involving the BT Pension Scheme.

‘The environment’ ranks low when choosing investments: Allianz Life

When deciding whether to invest in or do business with a company, U.S. investors give its social and governance behavior as much or more weight than its environmental record, according to Allianz Life’s ESG Investor Sentiment Study.

The study also found that most consumers believe companies focused on ESG issues have better long-term prospects.

When asked about the importance of a variety of ESG topics in their decisions to invest in a company, 73% of American consumers noted environmental concerns like natural resource conservation or a company’s carbon footprint/impact on climate change.

However, the same percentage emphasized social issues such as working conditions of employees or racial/gender equality, and 69% highlighted governance topics like transparency of business practices and finances or level of executive compensation.

About a third (34%) of respondents said a company’s stance on social issues was the most important factor in their decision to do business with a company, followed by 27% who ranked corporate governance issues as the top priority. Only 22% cited a company’s record on environmental issues as their chief concern.

Nearly 80% of those surveyed said they “love the idea of investing in companies that care about the same issues” they do, and 74% believe an ESG investment strategy is “not only one that you can feel good about, but one that makes long-term financial sense.” A full 71% percent also said they would stop investing in a company if it behaved in ways they consider unethical.

A significant gap still exists, however, actions and words. More than three-quarters of respondents (76% to 84%) said safe working conditions for employees, transparency in business practices and finances, living wages to employees, quality health insurance offerings, and natural resource conservation were important to them. Yet, fewer than half (40% to 44%) said they chose to invest/not invest based on those same business practices.

Investors more often choose to reward companies for good behavior rather than punish them for bad behavior.

Among the 16 ESG issues highlighted in the study, 11 issues were more influential in investors’ decision to actively invest, including carbon footprint/impact on climate change, charitable contributions, and involvement in reducing poverty and wages provided to employees. Only two issues were more influential in causing people to stop investing in a company: animal testing and donations to political candidates/PACs.

A complete list of ESG issues that impact investment decisions, as well as additional data from the ESG Investor Sentiment Study, can be found at www.allianzlife.com/ESG.

OASDI reserves rise $3 billion and gain a year of viability

The financial health of the OASDI (Old Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance) program improved a bit last year, its Board of Trustees announced this week. The combined asset reserves of the OASI and DI Trust Funds increased by $3 billion in 2018 to a total of $2.895 trillion.

The Social Security reserves are projected to run out in 2034, the same as last year’s estimate, with 77% of promised benefits payable at that time. The DI reserves are estimated to run out in 2052–20 years from last year’s estimate of 2032–with 91% of benefits still payable.

In their 2019 Annual Report to Congress, the Trustees announced:

In 2020, for the first time since 1982, the total annual cost of the program is projected to exceed revenue. The cost will remain higher throughout the 75-year projection period. Reserves are expected to decline during 2020. Social Security’s cost has exceeded its non-interest income since 2010.

The year when the combined trust fund reserves are projected to become depleted, if Congress does not act before then, is 2035 – gaining one year from last year’s projection. At that time, there would be sufficient income coming in to pay 80% of scheduled benefits.

“The Trustees recommend that lawmakers address the projected trust fund shortfalls in a timely way in order to phase in necessary changes gradually and give workers and beneficiaries time to adjust to them,” said Nancy A. Berryhill, Acting Commissioner of Social Security.

“The large change in the reserve depletion date for the DI Fund is mainly due to continuing favorable trends in the disability program. Disability applications have been declining since 2010, and the number of disabled-worker beneficiaries receiving payments has been falling since 2014.”

Other highlights of the Trustees Report include:

Total income, including interest, to the combined OASI and DI Trust Funds amounted to just over $1 trillion in 2018, including $885 billion from net payroll tax contributions, $35 billion from taxation of benefits, and $83 billion in interest. Total expenditures from the combined OASI and DI Trust Funds amounted to $1 trillion in 2018.

Social Security paid benefits of nearly $989 billion in calendar year 2018. There were about 63 million beneficiaries at the end of the calendar year.

The projected actuarial deficit over the 75-year long-range period is 2.78% of taxable payroll – lower than the 2.84% projected in last year’s report. During 2018, an estimated 176 million people had earnings covered by Social Security and paid payroll taxes.

The cost of $6.7 billion to administer the Social Security program in 2018 was a very low 0.7% of total expenditures. The combined Trust Fund asset reserves earned interest at an effective annual rate of 2.9% in 2018.

The Board of Trustees usually comprises six members. Four serve by virtue of their positions with the federal government: Steven T. Mnuchin, Secretary of the Treasury and Managing Trustee; Nancy A. Berryhill, Acting Commissioner of Social Security; Alex M. Azar II, Secretary of Health and Human Services; and R. Alexander Acosta, Secretary of Labor. The two public trustee positions are currently vacant.

View the 2019 Trustees Report at www.socialsecurity.gov/OACT/TR/2019/.

CBO expects slower real GDP growth in 2019

In CBO’s projections, the federal budget deficit is about $900 billion in 2019 and exceeds $1 trillion each year beginning in 2022. Over the coming decade, deficits (after adjustments to exclude shifts in the timing of certain payments) fluctuate between 4.1% and 4.7% of gross domestic product (GDP), well above the average over the past 50 years.

CBO’s projection of the deficit for 2019 is now $75 billion less—and its projection of the cumulative deficit over the 2019–2028 period, $1.2 trillion less—than it was in spring 2018. That reduction in projected deficits results primarily from legislative changes—most notably, a decrease in emergency spending.

Because of persistently large deficits, federal debt held by the public is projected to grow steadily, reaching 93% of GDP in 2029 (its highest level since just after World War II) and about 150% of GDP in 2049—far higher than it has ever been. Moreover, if lawmakers amended current laws to maintain certain policies now in place, even larger increases in debt would ensue.

Real GDP is projected to grow by 2.3% in 2019—down from 3.1% in 2018—as the effects of the 2017 tax act on the growth of business investment wane and federal purchases, as projected under current law, decline sharply in the fourth quarter of 2019. Nevertheless, output is projected to grow slightly faster than its maximum sustainable level this year, continuing to boost the demand for labor and to push down the unemployment rate.

After 2019, annual economic growth is projected to slow further—to an average of 1.7% through 2023, which is below CBO’s projection of potential growth for that period. From 2024 to 2029, economic growth and potential growth are projected to average 1.8% per year—less than their long-term historical averages, primarily because the labor force is expected to grow more slowly than it has in the past.

© 2019 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Scholarly research has since supported Innes’ premise. In his 2011 book, “Debt: The First 5,000 Years,” David Graeber writes, “There’s no evidence that [a barter economy] ever happened, and an enormous amount of evidence suggesting that it did not.” In a more recent example, Harvard law professor Christine Desan studied the history of the issuance of coins in Britain for her 2015 book, “

Scholarly research has since supported Innes’ premise. In his 2011 book, “Debt: The First 5,000 Years,” David Graeber writes, “There’s no evidence that [a barter economy] ever happened, and an enormous amount of evidence suggesting that it did not.” In a more recent example, Harvard law professor Christine Desan studied the history of the issuance of coins in Britain for her 2015 book, “