Prudential announces $3.2 billion in pension risk transfer deals

Prudential Retirement, a unit of Prudential Financial, Inc., has concluded $3.2 billion in previously undisclosed longevity reinsurance contracts, calling it “a further sign that pension de-risking activity in the U.K. is continuing at a brisk pace.”

As part of these transactions, The Prudential Insurance Company of America (PICA) assumes the longevity risk for approximately 13,200 retirees. The press release did not name the British pension sponsors involved.

The affordability of pension buy-ins and buy-outs is due in part to the improved funded status of U.K. schemes, which, on average, were at or near full funding in the summer of 2018. This improvement in funded status represents a marked increase over the last two years. This trend is driving the pension risk transfer business.

“The average U.K. pension scheme is at or near full funding, a material improvement over the last two years,” said Amy Kessler, head of longevity risk transfer at Prudential, in a release. “That is happening at the same time longevity improvements have slowed. Pensions are actively taking advantage of this environment by locking in these gains and transferring risk, knowing that such periods don’t last forever.”

These agreements follow at least 10 others during the last 12 months that are $1 billion or more in size, Prudential said.

Prudential has completed more than $50 billion in international reinsurance transactions since 2011, including a record $27.7 billion transaction involving the BT Pension Scheme.

New CEO at Thrivent: Terry Rasmussen

Thrivent announced this week that Brad Hewitt will retire as CEO and that Terry Rasmussen, president of Thrivent’s core fraternal business unit for the last three years, will succeed him.

Hewitt joined Thrivent in 2003 as chief fraternal officer. He was named COO in 2008 and CEO in 2010. He began his career with Securian in the Actuarial Services department. He held senior positions at UnitedHealth Group and Diversified Pharmaceutical Services.

Hewitt graduated from the University of Wisconsin-River Falls with a B.S. in mathematics. Rasmussen joined Thrivent in 2005. She was named president in 2015, after serving for 10 years as senior vice president, general counsel and secretary.

Before joining Thrivent, Rasmussen served in senior legal positions with American Express and Ameriprise Financial. At American Express she was responsible for global legal support of financial service products and services.

A former trial attorney in the U.S. Attorney General’s Honors Program, she received a BS in accounting from Minnesota State University-Moorhead and passed the CPA exam. She earned her JD from the University of North Dakota.

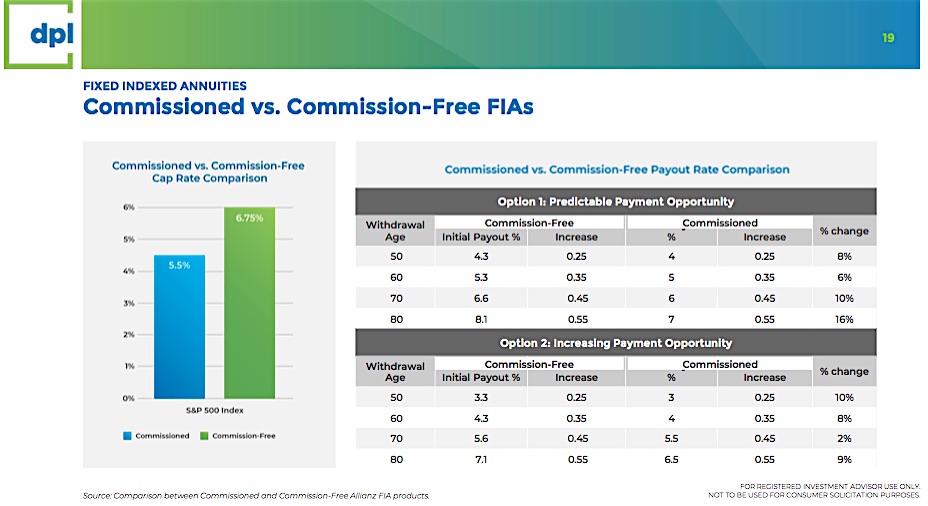

American Equity issues new FIA for retirement savers

American Equity Investment Life Insurance Company announced a new accumulation-oriented fixed index annuity product: AssetShield.

AssetShield “has a 175% participation rate on the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats with a two year point-to-point indexed strategy,” said Kirby Wood, Chief Distribution Officer of American Equity.

The AssetShield, with 5, 7, and 10 year terms available, offers multiple index crediting allocations – all backed by S&P indices, plus added access features for increased asset control.

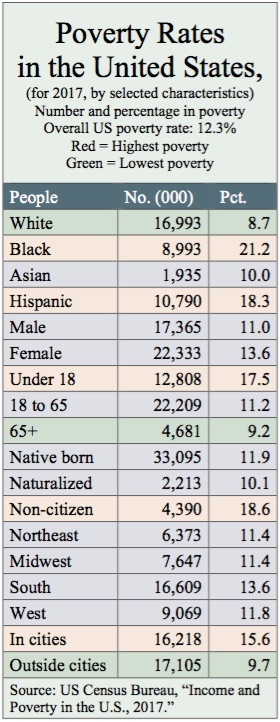

Warnings about federal debt… but not about private debt

The Concord Coalition has warned that the rising federal budget deficit–totaling nearly $779 billion in Fiscal Year 2018–reflects a structural gap between spending and revenues that is largely ignored in Washington even as it grows worse.

The Treasury Department this afternoon released the figure, which is $113 billion higher than 2017 deficit, along with other data for Fiscal 2018, which ended Sept. 30.

“Rather than taking advantage of this strong economy to improve the fiscal picture, Washington over the past year has made the situation worse,” said Robert. L. Bixby, executive director of The Concord Coalition, in a release.

Federal receipts for Fiscal 2018 totaled $3.33 trillion while spending totaled $4.11 trillion. The comparable figures for the previous year were $3,315 billion in receipts and $3,981 billion in outlays.

Roughly three-quarters of the spending growth came from mandatory spending programs and interest on the debt, which grow automatically. Revenue was essentially flat despite solid economic growth.

“Neither Democrats nor Republicans think this choice-less fiscal policy can go on forever,” Bixby said.

The 2018 deficit added significantly to the total federal debt, which now stands at nearly $21.6 billion. The Congressional Budget Office has previously projected that under current laws the federal government will begin running $1 trillion annual deficits in 2020.

The government’s interest costs in 2018 totaled $325 billion, a figure that is projected to rise rapidly in the coming decade and is $62 billion more than was spent last year.

Congress and President Trump approved deficit-financed tax cuts last December and deficit-financed spending increases earlier this year. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said last week that increases in defense spending were “very, very important,” and pointed out that Democrats wanted additional domestic spending in return.

The Concord Coalition is a nonpartisan, grassroots organization dedicated to fiscal responsibility.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.