Every retirement income plan has to start somewhere, and Jerry Golden begins by asking clients to use his online widget to calculate their “Income Power.” That’s the level of guaranteed monthly lifetime income they could squeeze out of their savings if they used all of it to buy a ladder of commercial deferred income annuities.

Jerry Golden

“The starting point is ‘Income Power,’” Golden, the CEO of Manhattan-based Golden Retirement, told RIJ in a recent interview. Income Power can be calculated for a single investor, a couple, or even include a beneficiary. If the clients think they can retire on that income, plus Social Security and pensions (if any), then Golden starts building a more specific retirement income plan for them. The Income Power number is a benchmark, not an plan.

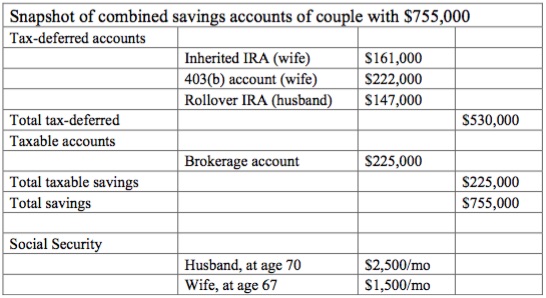

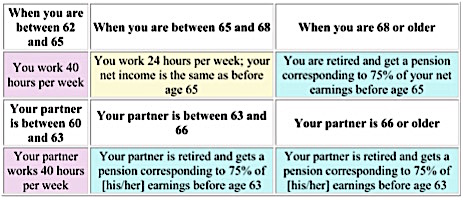

For this latest installment of our series of retirement income Case Studies, RIJ asked Golden to use his proprietary income planning process to create an income plan for a real but anonymous mass-affluent married couple, whom we’ll call the M.T. Knestors. The husband is 66 years old. He intends to claim Social Security in four years and then work part-time. Mrs. Knestor is 60 years old and already retired. They have two grown, self-supporting children.

The M.T. Knestors

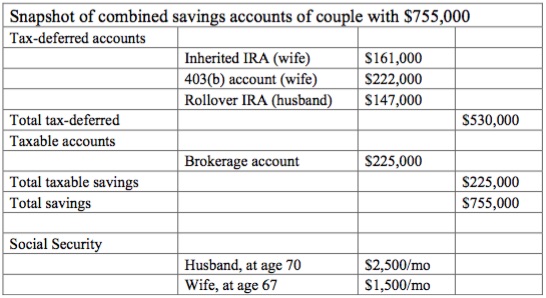

Here is the client data (shorn of specific asset allocations or products) that we sent to Golden Retirement:

Based on their $755,000 in assets, this couple’s Income Power is $2,900 per month at the start of the husband’s retirement, according to Golden’s software. With inflation adjustments, it rises to $4,900 after 15 years, when Mr. Knestor reaches age 85. But if this number isn’t part of the income plan, as noted above, why is it so important?

If deemed acceptable by the client, the Income Power number tells Golden if his clients have roughly enough savings not only to cover their monthly expenses in retirement, but also to offset inflation risk and longevity risk. If the couple considered their Income Power number too small to meet their expected retirement expenses, Golden would advise them to save more, retire later, reduce expenses, work part-time in retirement, or leverage their home by downsizing or borrowing against it.

Unless the Income Power number is high enough, creating a satisfactory plan would likely be a challenge. That’s why it’s important.

Jerry’s ground rules

After clients accept their Income Power as a good starting point, Golden can submit their specifics to his process. While every plan undergoes multiple changes during implementation, and each client will choose different sets of products, Golden’s general principles for creating a retirement income plan are:

Keep at least 65% of the portfolio in liquid investments. Golden believes that, as a general rule, no more than 30% to 35% of the assets should be annuitized. The client should think of the annuity purchase as part of the allocation to fixed income.

Purchase a qualified longevity annuity contract (QLAC). As a general rule, Golden recommends using 25% of each spouse’s tax-deferred savings (up to $130,000 each) to buy a deferred income annuity that begins no later than age 85. The QLAC provides late-in-retirement income to cover basic expenses plus supplement late-life health care costs if needed.

Invest remaining tax-deferred assets in a balanced portfolio. Golden recommends a systematic withdrawal program, based on conservative growth assumptions, that will exhaust the qualified assets between the date of retirement and the date when the QLAC income begins. (Favorable performance can either increase or extend withdrawals. See below.) He doesn’t believe in limiting withdrawals to the minimum required amount. The typical mass-affluent retiree, unlike high-net-worth retirees, needs the income and is less concerned with the tax consequences, Golden told RIJ.

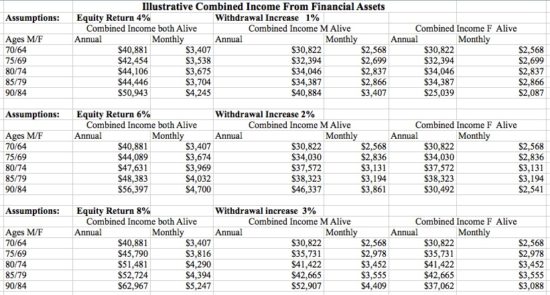

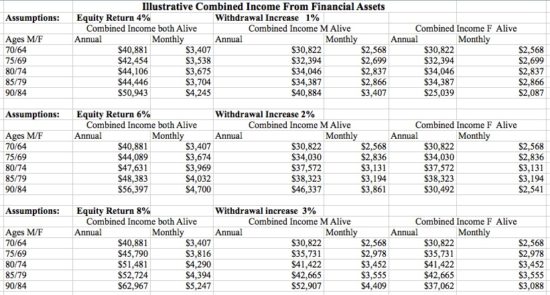

Increase withdrawals according to market returns. The clients can increase their income by 1%, 2%, or 3% per year, depending on whether equity returns are 4%, 6%, or 8%, respectively.

Invest taxable assets in dividend-paying stocks. The logic here is to draw down dividends as a supplement to monthly income while preserving the stocks for late-life expenses or bequests. These investments will potentially be eligible for the step-up in basis at death, and the capital gains tax relief that comes with it. To reduce risk, Golden recommends investing part of this allocation in high quality corporate bonds.

Buy an immediate income annuity if necessary. If the dividends, systematic withdrawals and QLAC income don’t produce adequate monthly income, Golden says, the client should consider using part of the savings to buy an immediate life annuity to make up the difference. When advising clients, he calls the immediate life annuity the plan’s “belt” and the QLAC its “suspenders.”

“Income allocation” is more important than “asset allocation.” Golden sees the client’s portfolio through the prism of income. He expects to allocate 25% to 40% of the client’s assets to the purchase of annuities, with the rest of the assets producing systematic withdrawals (from qualified accounts) and interest and dividends (from after-tax accounts).

The Knestors’ income plan

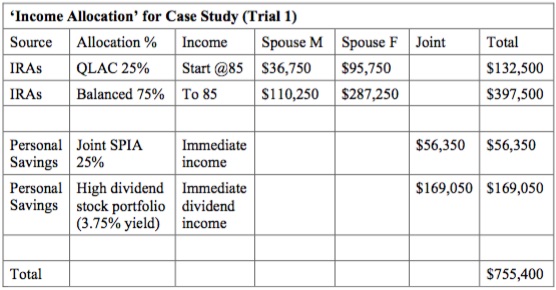

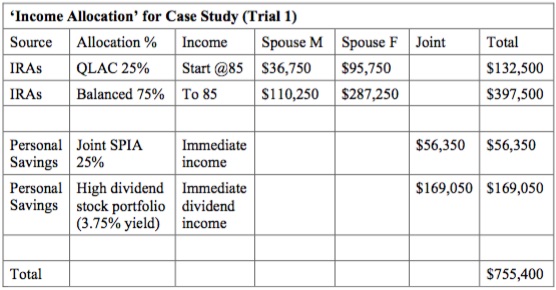

Based on these principles, the first draft of Golden’s plan (it may be amended and re-amended during future meetings) for the couple appears below. He used $132,500 (the sum of 25% of each spouse’s IRA savings) to buy a QLAC that would provide income when each reaches age 85. (The clients can adjust the start dates as they deem appropriate.)

Golden recommended putting the remaining pre-tax savings of about $400,000 in a 50% stocks/50% bond portfolio to provide systematic withdrawal income for 15 years, until the QLAC income starts. For additional monthly income over the entire retirement period, he put about $170,000 of the after-tax savings and put it into dividend-bearing stocks. He allocated the remaining $56,000 in after-tax savings to a small immediate, joint-life, inflation-adjusted income annuity. (In subsequent meetings, the couple could shift money from the high-dividend stocks to the immediate annuity, if they wanted more current income.)

Here’s the income chart that resulted from the allocations above:

This plan keeps most (75%) of the couple’s savings in liquid form (which will help them meet their goal to leave money to their children), while ensuring that more than half of their monthly income (including Social Security) is inflation-adjusted and guaranteed for life. The QLAC also acts a buffer against medical expense risk in late life. Overall, the plan delivers both upside potential and downside protection.

Perhaps because he has an insurance background, Golden is risk-conscious and doesn’t believe in the usual steps that many investment advisors take when creating an income plan, such as prescribing a systematic withdrawal plan based on the 4% rule solely against a portfolio of securities.

“Our fundamental approach is that asset allocation is all wrong for retirement income planning,” Golden told RIJ. He believes that Monte Carlo simulations, such as those that predict a 90% chance that a portfolio will last to age 90, are often based on market returns that most clients won’t experience because they sell stocks during a slump. “The biggest risk is persistency risk,” he said. “It’s wrong to assume that the client will be in the market every day between now and age 90. That’s just flawed.”

Scaling up the business

Golden finds new retail clients through his luncheon seminars, which he fills by sending email invitations to lists of executives in the New York-New Jersey-Connecticut area. His website and his blogposts also attract new clients, many of whom are already amenable to guaranteed income products and some of whom have already used his widget to calculate their Income Power. He also does targeted advertising in Kiplinger.com, where his articles are published in the Wealth Management section.

“We talk about minimizing risk,” Golden said. “Our income headline is ‘More Income, Less Market Risk, that’s what we want them to hear. The income annuity is just a tool. If we said we were going to create a 30% annuity plan, we’d lose people. When all is said and done, we look at the allocation and we see if we can meet the income goal by staying 65% liquid.”

Few people can match Golden’s level of expertise in the retirement income field. Over a 40-year insurance career, he’s been an actuary, home office executive, product developer, advisor and serial entrepreneur. At AXA-Equitable (now AXA US), he developed the first guaranteed minimum income benefit (GMIB) rider on a variable annuity. For MassMutual, he invented an income generation tool for advisors and retirees called the Retirement Management Account, or RMA.

Now, as a kind of capstone project, Golden is trying to scale up Golden Retirement and its Income Power methodology, which combines algorithms with human advice. So far he’s been bootstrapping his own web and software efforts. Eventually he’ll decide either to grow organically, license his technology to advisors, look for venture capital, or sell his mousetrap to a big financial services company.

“We know that we can drive interest and find high value prospects,” Golden said. “But then do we keep the clients ourselves and build up our own call center? Or do we send leads to third-party advisors? Or do we license our technology to various advisor platforms, or to larger institutions? We’re going through that decision-making process right now.” The opportunity for advisors to do well and do good by helping Boomers turn savings into sustainable income is, in his view, virtually unlimited.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.