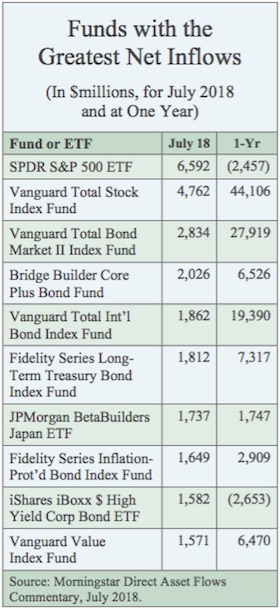

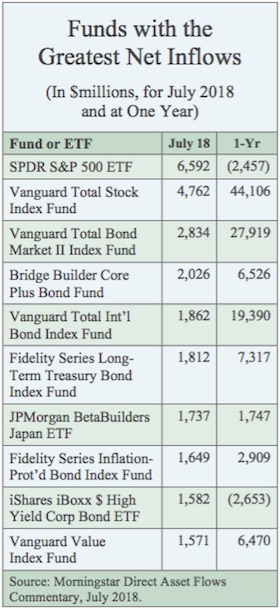

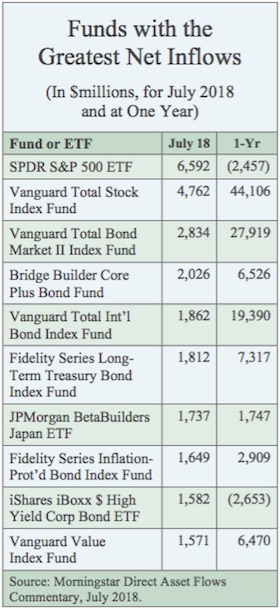

Funds with the Greatest Net Inflows, July 2018

IssueM Articles

Ascensus has entered into an agreement to acquire PenSys, a third-party administration (TPA) firm based in Roseville, CA. It will immediately become part of Ascensus’ TPA Solutions division.

So far in 2018, Ascensus has also purchased Continental Benefits Group, 401kPlus, INTAC, and ASPERIA.

PenSys is a nationally recognized TPA that specializes in the design, implementation, and administration of defined contribution, defined benefit, and cash balance retirement plans. The firm, which also offers 3(16) fiduciary services, has established a strong reputation for providing creative plan design and high quality service, Ascensus said.

Jerry Bramlett, head of TPA Solutions, said, “This addition to Ascensus TPA Solutions goes a long way toward helping us build a national TPA that offers a broad set of services and resources to financial professionals, employers, and employees.”

Raghav Nandagopal, Ascensus’ executive vice president of corporate development and M&A, said in a release, “This acquisition expands our California footprint significantly and adds to our capabilities to service clients nationally.”

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Allianz Life ranked as the top issuer of non-variable deferred annuity sales, with a market share of 7.8%, followed by AIG, Athene USA, Global Atlantic Financial Group, and New York Life, according to the latest edition of Wink’s Sales and Market Report for the second quarter of 2018.

Allianz Life’s Allianz 222 Annuity, an indexed annuity, was the top-selling non-variable deferred annuity, for all channels combined, in overall sales. It was the top-selling indexed annuity, for all channels combined, for the sixteenth consecutive quarter.

Indexed annuity sales for the second quarter were $17.3 billion; up nearly 22.0% when compared to the previous quarter, and up more than 18.4% when compared with the same period last year. Indexed annuities have a floor of no less than zero percent and limited excess interest that is determined by the performance of an external index, such as Standard and Poor’s 500.

Allianz Life was the top issuer of indexed annuities, with a market share of 12.7%, followed by Athene USA, Nationwide, Great American Insurance Group, and American Equity Companies. Allianz Life’s Allianz 222 Annuity.

Traditional fixed annuity sales in the second quarter were $875.0 million; up 19.9% from the previous quarter, and down 12.5% from the same period last year. Traditional fixed annuities have a fixed rate that is guaranteed for one year only.

Jackson National Life ranked as the top issuer of traditional fixed annuities, with a market share of 11.9%, followed by Modern Woodmen of America, Global Atlantic Financial Group, AIG, and Great American Insurance Group. Forethought Life’s ForeCare Fixed Annuity was the top-selling fixed annuity for the quarter, for all channels combined.

Multi-year guaranteed annuity (MYGA) sales in the second quarter were $10.0 billion; up 23.4% when compared to the previous quarter, and up 27.2 % when compared to the same period last year. MYGAs have a fixed rate that is guaranteed for more than one year.

New York Life ranked as the top issuer of MYGA contracts, with a market share of 18.1%, followed by Global Atlantic Financial Group, AIG, Protective Life, and Delaware Life. Forethought’s SecureFore 5 Fixed Annuity was the top-selling multi-year guaranteed annuity for the quarter, for all channels combined.

Structured annuity sales in the second quarter were $2.4 billion; up 12.6% from the previous quarter. AXA US ranked as the top issuer of structured annuities, with a market share of 40.2%. Brighthouse Life Shield Level Select 6-Year was the top-selling structured annuity contract for the quarter, for all channels combined.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

The U.S. life/annuity industry’s net income dropped nearly 13% in first-half 2018, according to a Best’s Special Report published this week. That decline, along with an increase in stockholder dividend payments, drove industry capital and surplus down by 1.8% compared with the prior year-end.

The report, “A.M. Best First Look—First Half 2018 Life/Annuity Financial Results,” is based on data from companies’ six-month 2018 interim statutory statements received as of Aug. 21, 2018, representing about 85% of total industry premiums and annuity considerations.

During the first half of 2018, the U.S. life/annuity industry experienced:

The trend of reduced cash and bond positions in the industry continued during the first half of 2018, with further increases to mortgage loans and other invested assets. Mortgage loans constituted 12.4% of total invested assets in the first half of 2018, up 41% from the first half of 2014.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

In a new partnership between Envestnet and Allianz Life’s entire portfolio of annuity products, including both advisory and commission-based products, will be available on the Envestnet Insurance Exchange, the two companies have announced.

The Envestnet Insurance Exchange, announced this past May, integrates insurance solutions into the wealth management process on the Envestnet platform. It is intended to streamline the annuity sales process.

With the new partnership, “advisors at banks, broker-dealers, independent insurance agencies and registered investment advisors (RIAs) throughout the United States will be able to research and potentially recommend Allianz Life annuity solutions as an option for their clients,” the release said.

“We have consistently heard from advisors that they want to offer more holistic solutions to help their clients achieve their financial goals,” said Tom Burns, chief distribution officer, Allianz Life.

The Envestnet Insurance Exchange can be accessed through various tools and features on Envestnet’s Advisor Portal. Envestnet has partnered with Fiduciary Exchange LLC (FIDx), a firm specializing in integrating advisory and insurance ecosystems, to develop and manage its Insurance Exchange, and the platform additions are scheduled to be available at the end of the year.

Financial advisors will need an insurance license to introduce insurance products. For those advisors who are not licensed, Envestnet will be offering a service called Guidance Desk that will allow unlicensed RIAs access to the consulting and fiduciary services that would enable them to use the Insurance Exchange. This service is still in development.

The Prudential Insurance Company of America, a unit of Prudential Financial, Inc., has assumed the longevity risk for about £1 billion (nearly $1.4 billion) in pension liabilities from Aviva Life and Pensions U.K. Ltd, in the first longevity reinsurance transaction between the two firms.

Prudential has executed more than $50 billion in international reinsurance transactions since 2011, including the largest longevity risk transfer transaction on record, a $27.7 billion transaction involving the BT Pension Scheme.

With the increasing affordability of pension risk transfer—a reflection of attractive pricing, enhanced capacity of insurers, and the improved funding ratio of U.K. pensions—many U.K. pension insurers are seeking longevity reinsurance arrangements, a Prudential release said.

Market activity in 2018 is building toward a very strong second half. Rising rates and equities, combined with lower-than-expected longevity improvements, mean that pension schemes are very well-funded and that de-risking is more affordable than ever. Leading pension schemes are taking advantage of this favorable environment by locking in gains and transferring risk,” said Amy Kessler, head of longevity risk transfer at Prudential, in the release.

The agreement follows at least 10 others in the market during the last 12 months that have exceeded $1 billion in size. Collectively, these U.K. longevity reinsurance and longevity swap agreements signify a noticeable market surge, driven by pension schemes eager to capitalize on their improved funded status, and take risk off the table.

Funding levels of U.K. pension schemes have improved markedly since the Brexit vote of 2016, boosted by fresh contributions, strong investment performance and higher gilt yields (which lower the present value of future liabilities).

Millennium Trust Company, LLC, a provider of retirement and institutional custody services to advisors, financial institutions, businesses and individuals, reported a strong quarter of performance in the second quarter of 2018. The firm also was recognized in the Crain’s Chicago Business Fast 50 as one of the top companies in the Chicago metropolitan area for outstanding revenue growth over the past five years.

In early July Millennium Trust announced an agreement with The Bancorp Bank (Bancorp) to acquire approximately 160,000 automatic rollover IRAs. After the transfer of accounts from that acquisition, Millennium Trust will have more than $24.5 Billion in assets under custody.

The acquisition builds on a successful quarter for Millennium Trust’s Retirement Services team that promotes retirement readiness in America. The firm now has more than 86,000 agreements with plan sponsors and more than 1 million individual retirement accounts.

Millennium Trust’s Institutional Custody Services team introduced a refreshed Millennium Alternative Investment Network (MAIN) in the second quarter. MAIN is a free research, education and alternative investment resource that informs investors and advisors about alternative assets, and provides access to streamlined investing processes.

Institutional Custody Services ended the second quarter with over $12.8 Billion in assets under custody in more than 450 private and public funds. The team reported almost 15,000 unique alternative assets under custody at the end of the quarter.

EY (Ernst & Young) will invest US$1 billion in new technology solutions, client services, innovation and the EY ecosystem over the next two financial years, commencing from July. In a release, EY described the outlay “as part of an ongoing strategy to provide clients and people with innovative offerings using the latest disruptive technologies.”

The investment, which augments an ongoing technology spend, will be used to develop new technology-based services and solutions in areas such as financial services, cyber, risk management, managed services, software services as well as digital tax and audit services, the release said.

In personnel matters, Nicola Morini Bianzino joined EY as Global Chief Client Technology Officer (CCTO), with Steve George as EY Global Chief Information Officer (CIO) and Barbara O’Neill, EY Global Chief Information & Security Officer (CISO). These appointments complement our existing investments in innovation including our global artificial intelligence (AI) and Blockchain labs, the EY release said.

Bianzino joined EY from Accenture, where he led AI and AI strategy. He also led Growth and Strategy for Accenture’s technology, innovation and ecosystems, which included new ventures, acquisitions and investments. Based in Silicon Valley, he will focus on bringing digital capabilities to clients so that technology is at the heart of the EY services.

Steve George was CIO for Citigroup’s North American retail banking, mortgage and global commercial banking teams. He has also worked at Accenture as well as Chase and Huntington Bank. He is based in New York and will focus on embedding digital technologies across EY teams globally.

Pacific Life has named Joe Celentano to the post of senior vice president and chief finance and risk officer of the company’s Retirement Solutions Division (RSD), effective January 1, 2019. He will succeed Dewey Bushaw, who is retiring after a 24-year career at Pacific Life.

Celentano, who joined Pacific Life in 1992, previously served as Pacific Life’s chief risk officer from 2012 to 2017 before joining RSD as the division’s financial and risk management operations. In his new role as executive vice president, he will focus on growth and innovation, while also continuing the expansion of product offerings and distribution channels. He will transition into his new role over the course of the fourth quarter in 2018.

Bushaw is retiring after a 24-year career with Pacific Life with many significant contributions, most notably his strong leadership in stewarding the division through a period of unprecedented growth and industry changes.

Only 1.1% of defined contribution plan participants stopped contributing during the first quarter of 2018, according to the Investment Company Institute’s “Defined Contribution Plan Participants’ Activities, First Quarter 2018” study, which tracks data on more than 30 million participant accounts in employer-based DC plans.

Other findings from the first quarter of 2018 include:

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has charged four Transamerica entities with misconduct involving faulty investment models and ordered them to refund $97 million to misled retail investors.

Investors put billions of dollars into mutual funds and strategies using faulty models developed by AEGON USA Investment Management LLC (AUIM) and used by Transamerica Asset Management Inc. (TAM), Transamerica Financial Advisors Inc., and Transamerica Capital Inc., the SEC said in a release.

“The models, which were developed solely by an inexperienced junior AUIM analyst, contained numerous errors and did not work as promised,” the SEC’s order said. “When AUIM and TAM learned about the errors, they stopped using the models without telling investors or disclosing the errors”

Without admitting or denying the charges, the four Transamerica entities agreed to pay nearly $53.3 million in disgorgement, $8 million in interest, and a $36.3 million penalty, and will create and administer a fair fund to distribute the entire $97.6 million to affected investors.

In separate orders, the SEC also found that Bradley Beman, AUIM’s former Global Chief Investment Officer, and Kevin Giles, AUIM’s former Director of New Initiatives, each caused certain AUIM’s violations. The two men agreed to settle the SEC’s charges without admitting or denying the findings and pay, respectively, $65,000 and $25,000 to affected investors.

David Benson, Anne Graber Blazek, and Paul Montoya of the Enforcement Division’s Asset Management Unit in the Chicago Regional Office, and Michael Cohn of the Asset Management Unit in the New York Regional Office conducted the SEC’s investigation.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

The idea of tacking a lifetime income benefit rider onto a buffered or structured indexed annuity is relatively new. Since AXA invented the buffered concept eight years ago, this type of product has been designed for accumulation and for investors who haven’t started thinking about retirement income per se.

But last May, Lincoln Financial’s new “Level Advantage” structured index annuity featured Lincoln’s patented i4Life variable income annuity as a option. Now Allianz Life has fitted a living benefit rider to its existing Index Advantage structured index annuity. The earlier version had an annuitization option but no living benefit.

The new product is called Allianz Index Advantage Income Variable Annuity. Other companies in this space can be expected to follow suit. [See today’s covered story on an ETF version of a buffered product.]

Structured annuity sales in the second quarter were $2.4 billion; up 12.6% from the previous quarter, according to Wink, Inc.’s latest survey. While AXA US is still the top issuer of structured annuities, with a 40% market share, the Brighthouse Life Shield Level Select 6-Year was the top-selling structured annuity contract for the quarter across all channels.

In terms of risk and return, structured index annuities occupy a middle ground fixed indexed annuities (FIA) and variable annuities (VA) in the annuity product spectrum. They offer more upside potential but less protection than an FIA. Conversely, they offer less upside potential than a VA but a measure of protection against loss that VAs don’t offer (except indirectly, through volatility-controlled funds).

The new Allianz product is loaded with options, which makes it flexible (which advisors like) but complex (which advisors say they don’t like). It offers four index options, two death benefit options, five combinations of performance caps and downside buffers and an income rider as standard equipment. There’s no deferral bonus (aka “roll-up”) on the income rider, but contract owners receive a modest hike in the annual payout percentage for every year they delay taking income after the initial purchase.

The product’s minimum purchase premium is just $5,000. It has a six-year surrender penalty schedule starting at 8.5%. There’s a 1.25% annual product fee (most of which reimburses Allianz Life for the commission it pays the agent) and a 0.70% annual fee for the income rider. The product currently comes only in a commissioned version.

.jpg)

Matt Gray

Matt Gray, senior vice president for Product Innovation at Allianz Life, told RIJ that Index Advantage is designed to compare favorably on price with variable annuities that have income riders.

“In looking at the traditional VA marketplace, we saw that advisors and broker-dealers don’t like the all-in fees of 330 to 350 basis points. We also saw, based on our ‘Chasing Retirement’ study, that there’s a large population of consumers who feel behind in their savings and want to catch up.”

Gray said that Allianz Life is emphasizing “the power of and” in the product. Where a traditional VA with living benefit offers income based on the higher of the benefit base or the account value, Index Advantage Income offers retirees a chance for higher payouts if they delay income and upside potential over the entire life of the product—even after income begins.

Contract owners get potential for gain through the ownership of options on any of these equity indexes:

The product also offers five combinations of upside potential and downside protection:

Once income starts, the client uses only the last two strategies above.

While gains from these strategies can boost annual income levels for contract owners, it’s important to remember that the product’s biggest benefits accrue to contract owners who live the longest and collect income for the highest number of years. The insurer doesn’t pay out any of its own money until after the client’s own money has been exhausted by income or fees.

By the same token, the longer the contract owner waits before taking a monthly income, the greater the annual income level. That’s based on the assumption that the income will be paid out for fewer years. The advantage of this type of product over a conventional fixed income annuity is greater liquidity and the chance (under one of the options) for rising income in retirement.

Here’s a hypothetical example of how this product would work, suggested by an example that Allianz Life uses in the brochure for this product:

A 55-year-old single woman puts $300,000 into the Index Advantage product. If she retires immediately, she can take out 4.50% or $13,500 per year. But the payout percentage rises by 30 basis points for every year she defers income. If she retires at age 60, she can take out 6% of her accumulation. If she retires at 65, she can take out 7.5% and if she waits until age 70, she can take out 9% per year.

In Allianz Life’s example, the woman waits 10 years, until she turns 65, to begin taking income. By then, she has accumulated a hypothetical $500,000. She then has two ways of taking income: a fixed income or a reduced initial income that can increase when one of the available market indexes goes up.

For instance, she can take the “level income” option and receive $37,500 per year for life (0.075 x $500,000). Or, if she can choose the “increasing income” option and take a lower initial payout of $32,500 but maintain exposure throughout retirement to one of the four market indexes. After the $32,500 income begins, she must use one of the two Index Protection Strategies for future growth.

Gray said that the income from Index Advantage Income should compare favorably with the income from a traditional VA with a guaranteed lifetime withdrawal benefit.

“In back-test studies we’ve done, 61% of the time the contract owner had a starting income that was at least 10% more than the income produced by a traditional variable annuity,” he told RIJ. “The average starting income was 34% higher than a VA’s. Fourteen percent of the time, a variable annuity would produce a starting income at least 10% higher than Index Advantage, with an average starting income that was 18% higher.”

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Higher interest rates and relief from regulatory pressure helped drive up sales of most types of annuities in the second quarter of 2018. Fixed indexed annuity (FIA) posted record sales of $17.6 billion in the quarter, according to LIMRA Secure Retirement Institute’s latest survey.

“This quarter’s FIA sales topped the record set in the fourth quarter 2015 by 12%,” said Todd Giesing, annuity research director, LIMRA Secure Retirement Institute. FIA sales were 17% higher than second quarter 2017 and 21% percent higher than first quarter 2018 sales results.

“All of the top 10 manufacturers reported double-digit growth from the first quarter 2018. With the Department of Labor’s (DOL) fiduciary rule vacated and the prospect of continued rising interest rates, demand for this product is high,” Giesing said.

FIA sales were 32.1 billion in the first half of 2018, up 14% from the first half of 2017.

Sales of fee-based (no commission) FIAs, which represent about one-half of one percent the total FIA market, were $67 million in the second quarter.

Before the Trump administrator and the federal court of appeals eliminated the Obama Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule, the rule had put a chill on sales of FIAs and VAs. It required commission-paid sellers of those products to pledge to act in the best interests of IRA-owning clients and not their own. That requirement has vanished, and with it the potential for lawsuits against agents who put self-interest first.

More FIA growth predicted

LIMRA SRI expects FIA sales to grow 5% to 10% in 2018 and to exceed the prior annual sales record of $59.1 billion. It also expects FIA sales to keep growing in 2019 and 2020.

Total annuity sales were $59.5 billion, 10% percent above the second quarter 2017 results and 15% higher than the first quarter. Sales last reached this level in the first quarter of 2015. Fixed annuity sales drove most of this quarter’s growth; they have outperformed variable annuity (VA) sales in eight of the last 10 quarters.

Year-to-date, total annuity sales were $111.3 billion, five percent higher than in the first half of 2017. LIMRA SRI expects a five to ten percent increase for annuity sales this year and zero to five percent growth in 2019.

After 17 consecutive quarters of declines, VA sales improved two percent to $25.8 billion in the second quarter. VA sales were $50.4 billion in the first two quarters of 2018, level with prior year results.

“Despite introducing new products and making changes to enhance their existing products to make them more competitive, companies are not having the same success with VAs as they are with fixed annuities,” noted Giesing. “However, the new and enhanced VAs, combined with the vacated DOL rule and better economic conditions, have led to slightly improved sales.”

Fee-based VAs sales, which represent only 3.3% of the total VA market, rose 49% from the second quarter of 2017, to $850 million.

In the second quarter, sales of registered indexed-linked annuities increased 6% from the prior year, to $2.5 billion. Sales growth has slowed as rising interest rates made competing products more attractive. These products represent about 10% of the retail VA market.

LIMRA SRI predicts total VA sales to increase less than five percent in 2018.

Total fixed annuity sales were $33.7 billion in the second quarter, up 18% from the second quarter of 2017. Year-to-date, total fixed annuity sales were $60.9 billion, up nine percent from the first half of 2017.

Sales of fixed-rate deferred annuities (book value and market value adjusted or MVA) benefited from the higher interest rates, rising 23% in the second quarter to $11.4 billion. Quarterly sales have not been this high since the first quarter 2016. Year-to-date, fixed rate deferred annuity sales were $20.1 billion, four percent higher than the same period of 2017.

“We believe fixed-rate deferred sales will have a strong second half of the year, based on the prospect of continued interest rate increases,” Giesing said. LIMRA SRI predicts fixed-rate deferred annuity sales to increase 15% to 20% percent this year and by as much as 25% in 2019.

Immediate income annuity sales jumped 14% in the second quarter, to $2.5 billion. This represented the highest quarterly sales in two years. In the first half of 2018, immediate income annuity sales were $4.6 billion, 10% higher than the prior year.

The only annuity product without positive sales growth was deferred income annuities (DIA). DIA sales fell four percent in the second quarter, to $575 million. DIA sales were $1.1 billion in the first half of 2018, down five percent from prior year.

“Rising interest rates will benefit income annuity sales. LIMRA SRI is forecasting five to ten percent growth in 2018,” said Giesing. “These products offer a unique value for retirees and pre-retirees seeking protected accumulation and guaranteed lifetime income features.”

Second quarter 2018 Annuities Industry Estimates and the ten-year annuity sales trends are located in LIMRA’s Data Bank. LIMRA Secure Retirement Institute’s Second Quarter U.S. Individual Annuities Sales Survey represents data from 95% of the market.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Ever since “buffered” (or “structured” or variable) indexed products appeared in 2010, life insurers have had this growing market virtually to themselves. Starting with AXA’s Structured Capital Strategies, each product has been built on an annuity chassis. In the 2Q2018, category sales reached $2.4 billion, up 12.6% year-over-year.

Now an asset management firm has entered the field. Earlier this month, Innovator Capital Management launched what it claims are the first products of this type to be built on an ETF (exchange-traded fund) chassis. Milliman Financial Risk Management LLC is the subadvisor.

The three Innovator ETFs invest in multiple options on the S&P500. Investors purchasing shares of the ETFs earn gains up to a cap and have limited or buffered exposure to losses, over an outcome period of approximately one year. In the past, the only non-annuities to offer similar performance were structured notes.

This month Innovator rolled out a suite of related ETFs, each with a different range of possible gains or losses:

The initial outcome period for PJUL and UJUL runs from August 8, 2018 to June 30, 2019. BJUL was listed on August 29, 2018 and also runs through June 30, 2019. At the conclusion of the outcome period the ETFs will not expire or terminate. Instead, they will roll into a new set of options positions, and the cap and buffer will “reset.” Investors who jump into the funds mid-term will receive adjusted caps and buffers, which can be viewed real-time via a pricing tool on Innovator’s website.

Bruce Bond

“These types of payouts were originally available as structured notes, and many people are familiar with those products and how they work,” said Bruce Bond, co-founder and CEO of Innovator Capital Management, based in Wheaton, IL. “Our goal is to deliver that type of payout in the most efficient, low-cost way possible, and have it qualify for all the fiduciary accounts.”

Innovator is the ETF sponsor and will be selling the product, Bond told RIJ. “Our first effort will be to work with advisors who are fiduciaries who wouldn’t ordinarily use a structured product or an annuity. They currently have no access to this type of product in ETF form,” he said.

Investors in these products buy shares, just as they would any other ETF. Their investments are applied to the purchase of customized options on the S&P 500 Index. Investors in the ETFs own the options directly and bear the investment risk. The products involve no bond underwriter or insurance company, which makes them cheaper and more transparent than structured notes or annuities.

“When we talk to financial advisors, they often ask, ‘how else can I access structured outcomes? What do we do for the portion of our clients who might not want annuities or structured notes? This gives them a similar strategy in a liquid, transparent manner, and at a lower cost,” added Matt Kaufman, Principal and Senior Director, Product Development at Milliman.

“When you look at the structured outcome marketplace,” he added, “the sales process often involves a major decision about tying up a large portion of someone’s wealth for a considerable period of time, often with relatively low transparency and liquidity during the holding period,” he said.

“We find placing structured outcome strategies in the ETF wrapper provides a more transparent, liquid and accessible option for many people needing to access the growth of the equity markets, in a more defined or risk-managed way.”

Here’s how Innovator describes the ETFs:

“Each Fund will hold a portfolio of custom exchange-traded Flexible exchange options (FLEX options) that have varying strike prices (the price at which the option purchaser may buy or sell the security, at the expiration date), and the same expiration date (approximately one year). The layering of these FLEX Options with varying strike prices provides the mechanism for producing a Fund’s desired outcome (i.e. Cap or buffer). Each Fund intends to roll options components annually, on the last business day of the month associated with each Fund.”

Cboe describes FLEX options as the only listed options that allow users to select option contract terms. The underlying index, option type, exercise date, strike price, and settlement date are all customizable. These options also give investors the opportunity to trade on a larger scale with expanded or eliminated position limits.

Though the defined outcome parameters are set at yearly intervals, the products have all the liquidity associated with owning an ETF. Investors can trade them intra-day, and each ETF’s share price fluctuates based on the performance of the underlying options positions, which in effect should move at some ratio (or delta) relative to the S&P 500. That ratio will be closer to 1:1 as the outcome period draws closer to its conclusion.

“As a result, the upside cap and buffer levels will be different for each investor who buys shares of an Innovator Defined Outcome ETF during the outcome period, but these outcome values can all be known prior to investing,” Kaufman said.

Each of the ETFs has an expense ratio of 79 basis points a year. If the gains on the product were capped at 10% of the S&P500 Index, for instance, the investor would face an effective cap of 9.21%. Assuming that an advisor charges an annual management fee on the market value of the investor’s entire portfolio, that too would reduce an investor’s overall portfolio returns.

Innovator conceived these products at a time when it appeared that the DOL fiduciary rule would soon take effect, and that it would become more difficult for advisors to sell commissioned products to owners of rollover IRAs, which now have a collective value of about $9 trillion. ETFs do not have sales loads or commissions.

In choosing a subadvisor for its new product, Innovator logically picked Milliman, which had worked with Cboe and Standard & Poor’s to create four series of Cboe S&P500 Target Outcome Indexes, which are the benchmarks for the Innovator series. Cboe owns the indexes and licenses them exclusively to Innovator. Terms of the exclusivity were not made public, but other product structures outside of the ETF may be able to build products based on target outcome indexes.

“As the structured annuity, indexed annuity and ETF spaces develop, the appetite for structured outcomes that are built directly into the index methodology may increase,” Kaufman said.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Millennials believe as much in space aliens as in the long-term viability of Social Security, surveys show. Economists, fortunately, tend to have more faith in the national pension program than in ETs, and some them—economists, that is—spend a lot of time looking for ways to fix it by 2034, when its reserves run dry.

The question is not whether it’s possible to recharge Social Security’s finances within the next 16 years, but how to do it. Some economists believe that if more Americans worked a couple of years longer and claimed benefits later, the system might recover solvency without politically ugly tax hikes or benefit cuts.

If no action is taken, Social Security will be able to pay only 75% of its promised benefits after 2034. To solve that problem today, the government would have to raise payroll taxes (to about 15% from 12.4%), cut benefits across-the-board by 17%, or some combination of the two. It could also generate more revenues by raising the cap on the amount of earned income—currently the first $128,400—on which the payroll is levied.

The overlap of Social Security policy and behavioral finance was the subject of several papers aired at the Retirement Research Consortium’s 20th annual meeting last week. The National Bureau of Economic Research and the Centers for Retirement Research at Boston College and the University of Michigan produced the meeting at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C.

Academic proposals for improving Social Security’s finances tend to be math-heavy and wonkish. But they contain the seeds of potential policy solutions. In a paper he presented at the meeting, John Laitner of the University of Michigan suggested tweaking the arcane calculation of Social Security benefits so that claiming benefits at age 63 would yield significantly more income than claiming at age 62. (In 2013, 48% of women and 42% of men claimed at age 62, according to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

The lure of higher benefits, Laitner’s calculations showed, could motivate Americans to work an average of 1.2 to 1.8 years longer before filing for benefits. That modest increase, he said, could provide enough new revenues from payroll taxes and federal income taxes to offset 20% to 30% of the Social Security shortfall.

Economists in other countries, including Italy and Germany, have also been working on ways to force or nudge people who are near retirement to keep working for a while. For instance, after the 2008 financial crisis, the Italian government abruptly raised the full public pension age for men to age 66 from age 65 and began gradually raising the full pension age for women from age 60 to age 66. Starting in 2021, no workers will be able to receive a full pension before age 67.

This somewhat desperate move was driven by Italy’s flirtation with national bankruptcy, and it backfired, at least in the short run. According to a paper presented at the meeting by Matteo Paradisi of Harvard, delays in the retirement dates of older workers caused employers at small to mid-sized companies to lay off middle-aged workers.

Some of those laid-off workers turned to tax-financed social services, thereby offsetting some of the fiscal benefit of the higher retirement age. “One-half to two thirds of revenues generated by the reform are lost in the short-run due to the behavioral responses of firms and workers,” wrote Paradisi and his co-author, Giulia Bovini of the London School of Economics and the Bank of Italy.

Other interventions can encourage people to retire earlier. A quarter-century ago, through the Pension Reform Act of 1992, Germany began paying bonuses to workers whose expected public pension benefits were depressed because, despite long work histories, their incomes had never been high. The program didn’t apply to people who began contributing to the pension after 1992.

At the conference, researcher Han Ye of the University of Mannheim (Germany) shared the results of her investigation of the effects of that program. She found that, because the bonuses caused women to claim pensions and leave the workforce earlier, the program was a fiscal failure.

According to her study, an offer of 100 euros in additional monthly pension benefits induced women to claim old age pensions about 10 months earlier than before. The subsidy also raised the rate at which women claimed a pension at age 60 by 17%. “In order to raise the lifetime income of the low-income pensions by one euro, 1.3 euros have to be raised by the government, either via taxes or pension contributions,” Ye wrote.

Other research papers presented at the meeting showed:

Fears that the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) would hurt the American economy by reducing the supply of workers are not justified by research data, according to a study by Helen Levy and Tom Buchmueller of the University of Michigan and Sayeh Nikpay of Vanderbilt University.

When the ACA, also known as Obamacare, went into effect in 2014, the media carried many reports that the ability to obtain health insurance outside the workplace would cause many workers to leave benefits-paying jobs. But, after analyzing trends in health insurance coverage and labor market outcomes for Americans ages 50 through 64, the researchers found “no discernible break” in the labor market participation rate in 2014, either in states that expanded their Medicaid programs or in those that did not.

Another team of researchers studied the correlation between the growing use of factory robots and on rising imports from China from 1994 to 2015 on U.S. earnings that are subject to the payroll tax, which generates Social Security program revenues.

Rising use of robotics in manufacturing was correlated with a drop of more than 3% in earnings subject to the payroll tax for Americans in the upper 60% of the income spectrum. Rising imports from China coincided with reductions in the earnings of those in the bottom half of the income spectrum by at least three percent, and reduced the earnings of lowest-earning Americans by as much as 12%.

Matthew Rutledge, Gal Wettstein and Wenliang Hou of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College and Patrick J. Purcell of the Social Security Administration wrote the study.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Lincoln Financial Group has introduced YourPath portfolios, a series of target date portfolios for employer-sponsored retirement plans that use investments offered by American Funds, American Century Investments, BlackRock and State Street Global Advisors.

The portfolios “will be managed along multiple risk-based paths to support a more personalized investment approach based upon financial circumstances and risk tolerance,” a Lincoln press release said. The three available paths are Conservative, Moderate and Growth.

“When selecting YourPath as the QDIA, the default criteria will be selected by the plan sponsor,” a Lincoln spokesperson told RIJ. “The participant age will default the participants into the correct target date vintage, then the plan sponsor can select the default risk path they find most prudent for their participant population. The participant individually would have the ability to opt into another risk path after reviewing their appropriate risk tolerance.”

The funds in the YourPath program will be institutionally priced, Lincoln said. The YourPath American Funds Portfolios will range in annual expense ratio from 0.33% to 0.46%, YourPath iShares Portfolios will range in price from 0.12% to 0.15%, and YourPath American Century/State Street Global Advisors will range in price from 0.44% to 0.55%.

“Unlike standard target date funds driven by retirement age, Lincoln Financial’s YourPath portfolios are a more customized solution,” said Ralph Ferraro, senior vice president, head of Product for the company’s Retirement Plan Services business, in the release.

YourPath portfolios will offer an active, passive or hybrid portfolio investment strategy with a stable value asset class to help reduce market volatility. Morningstar Investment Management LLC will provide the glide path, portfolio construction and ongoing management for each of the portfolio strategies, delivering fiduciary support as an investment manager under ERISA 3(38), the release said.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Eagle Life Insurance Company, a wholly owned subsidiary of American Equity Investment Life Insurance Co., has added a five-year fixed index annuity (FIA) product to its indexed product lineup: Eagle Select Focus 5.

The contract allows clients the ability to take penalty-free withdrawals of either 5% or 10% per year during the five-year surrender charge period, beginning with the start of the second contract year. The 5% withdrawal option requires election of a market value adjustment rider.

Eagle Select Focus 5 also offers flexible premiums that don’t extend the surrender period, a five year surrender charge schedule, terminal illness and nursing care riders included at no cost and transparent crediting methods, said Kirby Wood, Chief Distribution Officer of Eagle Life, in a release.

Eagle Select Focus 5 offers a new allocation option: the “S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats Daily Risk Control 5% Excess Return with Participation Rate.” There is no upper limit on the potential rate of return the owner can receive when allocating premium to this index option, but the internal design of the index automatically dampens the owner’s upside potential.

According to an Eagle Life product brochure, this is “a volatility control index that consists of the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats Index and a cash component accruing interest at three Month LIBOR.

“The Index is dynamically adjusted between the two components to target a 5% level of volatility. The S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats Index is made up of S&P 500 members that have followed a policy of consistently increasing dividends every year for at least 25 consecutive years. This Index is well diversified across all market sectors.”

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

In the past couple of weeks, we have learned that the economy may be growing more quickly than we had anticipated. That raises the fear that inflation could begin to rise more rapidly which, in turn, could cause the Fed to accelerate its previously described path towards higher interest rates.

But, thus far, the inflation rate has remained very much in check, which should keep the Fed on a go-slow approach towards higher rates.

Second quarter GDP growth came in at a solid 4.1%. But we should not forget that first quarter growth was relatively anemic at 2.2%. Thus, GDP growth in the first half of the year now stands at 3.1%. In the past year GDP growth has averaged 2.8%. So, while growth appears to be gathering some momentum, the economy does not appear to be in danger of overheating. Consistent GDP growth of 4.0% would be a problem; growth of 3.0% is sustainable.

Some economists are quick to point out that the trade gap narrowed significantly in the second quarter as businesses adjusted the timing of their exports and imports in advance of the implementation of tariffs. As a result, trade boosted GDP growth by 1.2% in the second quarter. It will not do that again in subsequent quarters, so they conclude that second quarter growth was an aberration. Their comments about the trade component’s contribution to GDP growth are accurate.

However, business inventories declined $27.9 billion in the second quarter and subtracted 1.0% from GDP growth in that quarter. That, too, will not be repeated later this year. In the third and fourth quarters rebounding inventory levels should boost GDP growth by as much as they subtracted from GDP growth in the second quarter. We have no hard data yet for the third quarter. However, we will take a stab at third quarter GDP growth of 3.1% and something like that in the fourth quarter. If all of that is correct, GDP growth in 2018 will be 3.1% compared to a 2.5% growth rate last year.

The second piece of robust economic news was the employment report for July. While employment climbed by a modest 157,000 in July, upward revisions to May and June mean that in the past three months payroll employment has risen 224,000 per month. That is steamy. Given a steady died of robust gains in employment and an unemployment rate that is currently 3.9% and falling, shouldn’t we worry about escalating wage pressures? Yes. But it does not necessarily follow that upward pressure on wages will translate into a problematical increase in inflation. Here’s why.

This past week we also got the employment cost index, which measures the gains in wages, benefits, and total labor costs. Total employment costs rose 2.4% in the second quarter and they have climbed 2.8% in the past year as both wages and benefits are on the rise. The tightness in the labor market is causing upward pressure on labor costs.

However, as we have noted on numerous occasions, we should be looking at labor costs adjusted for the increase in productivity, which economists call “unit labor costs.” Why? Because higher labor costs can be offset by increased productivity. If an employer pays its workers 3.0% higher wages because they are 3.0% more productive, he or she really does not care. The firm is getting more output. The worker has earned his fatter paycheck. In that case, unit labor costs, or labor costs adjusted for the increase in productivity are unchanged, and there will be absolutely no reason for that employer to raise prices. So, what is happening to unit labor costs currently?

The productivity report points out that compensation has risen 2.5% in the past year, but recent quarters have been around the 3.2% mark.

If compensation in the past four quarters has risen 2.5% and productivity has climbed by 1.3%, then unit labor costs in that same time have risen 1.2%. Remember, the Fed has a 2.0% inflation target. If labor costs after adjustment for productivity are rising 1.2%, there is no way the current degree of tightness in the labor market will push the inflation rate higher.

For what it is worth, we expect compensation to increase 3.5% in 2018 as the tightness in the labor market pushes wage compensation steadily higher. But we also expect productivity to rise 1.3%. This means that labor costs this year should rise just 2.2%. It does not appear that the tightness in the labor market will cause a problem for inflation any time soon.

If all the above is true, the Fed is not going to be concerned about the combination of faster GDP growth and rising wages. It needs to have some reason to think that the inflation rate is going to pick up substantially. We believe that the “core” personal consumption expenditures deflator will rise 2.2% this year compared to the Fed’s target of 2.0%. The Fed will not regard that as a problem.

Having said that, the Fed should maintain the interest rate glide path it has described, which will boost the funds rate to the 3.2% mark by the end of next year and on to 3.4% by mid-2020.

© 2018 Numbernomics.com.

The Trump administration is about to finish shutting down one of the Obama administration’s key responses to the lack of retirement plans at tiny companies—the myRA program of auto-enrolled Roth IRAs—and is moving any remaining IRAs set up under the plan to a new custodian.

A notice on the Treasury Department’s myRA homepage warned myRA owners who have not yet moved their myRAs to a new custodian that the “open account in your name will be closed in September 2018 and the balance moved to a new Roth IRA in your name at Retirement Clearinghouse, LLC (RCH), a private sector IRA provider located in Charlotte, NC. The previous custodian was Comerica Bank.

Information on the number or combined dollar value of the accounts was not available.

RCH, formerly Rollover Systems, has for several years been seeking regulatory approval for a clearing system that would automatically transfer 401(k) assets from a former employer’s plan to a current employer’s plan whenever a participant changes jobs. Between plans, the assets would be warehoused at RCH. RCH says such a system would support continuity of saving and increase retirement security.

The myRA program grew out of an idea, developed more than a decade ago by David John (now of AARP) and J. Mark Iwry (now at Brookings Institution; a Treasury Department official under Obama), to create a workplace retirement savings program for employees at companies where no 401(k) or other savings program existed.

With no requirements for employers except to accommodate employee contributions through their payroll systems, the program offered employees a chance to begin saving in a Roth IRA. Initial contributions to the accounts had to be invested in U.S. Treasury securities to avoid volatility; when the accounts reached a value of $15,000, they could be transferred to a brokerage IRA at a private fund company and the assets diversified.

Before it was abruptly canceled in 2017, the myRA program was also expected to be used as a transition tool during the roll-out of state-sponsored auto-enrolled Roth IRA programs, such as OregonSaves and the California Secure Choice Retirement Plan. Those program resemble the myRA program, but at state level instead of a national level.

According to the notice:

“If you would prefer to withdraw your myRA account balance or transfer your account balance to another Roth IRA instead of having your account balance moved to RCH, you must act soon. The deadline for completing these actions is August 31, 2018. Because there is lead time needed to complete certain actions, in some cases the deadline for submitting action to myRA is August 17, 2018.

“For two years, there will be no account maintenance fees or fees associated with withdrawals, transfers, or the closure of your RCH account. RCH will also take over customer service responsibilities related to your soon-to-be closed myRA account, such as providing you with applicable tax forms, even if you close your account prior to the transition to RCH.

“Treasury announced the phase-out of the myRA program in July 2017, and stopped accepting new enrollments at that time. In December 2017, the program stopped accepting contributions (deposits). On a recurring basis, myRA account holders have been sent emails and letters to notify them that the program is being phased out and that they have the option to transfer their account balance to a private sector Roth IRA of their choosing.

Closing the remaining accounts and transitioning the balances to RCH will bring the program to an end. After the transition of your funds to a new Roth IRA with RCH, your funds will no longer remain in an investment issued by the Treasury, and Comerica Bank (the current Treasury-designated custodian) will no longer be custodian of your account. The new accounts with RCH will not be myRA accounts.

A Treasury press release from July 2017 set out the reasons for why the myRA program is ending. As noted in that statement, “The U.S. Department of the Treasury today announced that it will begin to wind down the myRA program after a thorough review by Treasury that found it not to be cost effective. This review was undertaken as part of the Administration’s effort to assess existing programs and promote a more effective government.”

Headquartered in Charlotte, NC, Retirement Clearinghouse, LLC (RCH) is a financial services organization that works with Individual Retirement Account holders, retirement plan service providers and investment providers. RCH has two wholly-owned subsidiaries: RCH Securities, LLC, a member of FINRA and RCH Shareholder Services, LLC a registered transfer agent with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

To the extent that the U.S. has a “retirement policy,” its flavor has definitely changed since Nov. 2016. Given the fact that a business-oriented administration has replaced a consumer-oriented administration, this should not be a surprise. It’s interesting to see who is taking the lead in setting policy today.

For one thing, the pro-Wall Street SEC, not the pro-consumer Department of Labor, is setting the standard for advisor ethics. The Obama DOL aimed to apply the protections and restrictions of the closely-regulated pension world to the tax-deferred IRA world. The SEC seems to tolerate rougher play in the advisory world, and seems satisfied with a caveat-emptor standard that will require consumers to watch out for their own best interest.

Regarding conflicts-of-interest in the advisory world, the Obama DOL tried to sharply reduce them (in part by demanding a written pledge of loyalty to clients from advisors selling variable and indexed annuities on commission) while still allowing business to proceed. For the financial industry, those same conflicts-of-interest—symbiotic relationships between product manufacturers and distributors—are the synergies at the very heart of its business models.

Industry opposition to the Obama fiduciary rule eventually led to its demise at the hands of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. It remains to be seen what the SEC will do. The public comment period for its vaguely-worded “Regulation Best Interest” proposal just ended.

In the retirement income arena, the action has shifted from the executive branch to the legislative branch. Under Obama, the Treasury Department drove the government’s thinking about financial products for tax-deferred accumulation and distribution.

Mark Iwry at Treasury, for example, initiated the myRA workplace IRA program for savers at companies without 401(k) plans. He also initiated the Qualified Longevity Annuity Contract, now offered by a handful of mutual life insurers. It allows people who buy deferred income annuities with a portion of their tax-deferred savings (up to 25%) to defer required minimum distributions on that portion until income begins or age 85, whichever comes first.

That era is over largely over. The newest and most talked-about retirement ideas are bubbling up from the legislative branch. Utah Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch has proposed the Retirement Enhancement and Security Act (RESA) of 2018 and Massachusetts Democrat Rep. Richard Neal is sponsoring the Retirement Simplification and Enhancement Act.

The Hatch bill would allow retirement plan providers to sponsor 401(k) plans and invite dozens of employers to join. The Neal bill would reduce or even eliminate the legal liabilities that are said to deter many small company employers from sponsoring 401(k) plans. There are several other initiatives in the mix as well.

These efforts appear to reflect a spirit of deregulation in keeping with the new administration’s preferences. The new initiatives would relax some of the regulations of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) and allow plan providers, including life insurers who are also plan providers, to sponsor and design 401(k) plans. If employers do bear less fiduciary responsibility for plan design in the future, insurers might even pre-build income annuities in 401(k) plans. Employers have been resistant to in-plan annuities because of liability concerns.

The Trump administration styles itself as “populist,” but the Obama approach to retirement was arguably much more populist, if populism and consumerism are at all related. The myRA and the QLAC ideas were aimed at the neediest, with their benefits tailored mainly to the accumulation and distribution challenges of individual lower- and middle-income Americans.

These initiatives offered only mild opportunities for people in the retirement business. By contrast, there’s a lot of excitement in the 401(k) industry about the Hatch and Neal bills. Those bills would make the small plan market more accessible to large service providers. Whether they would result in the availability of 401(k) plans to millions of currently uncovered American workers remains to be seen.

The new legislative proposals are said to have a 50% chance of becoming reality, perhaps as part of the next phase of tax reform. Given the gridlock and dysfunction in Washington, D.C.—a city that grows more opulent even as government decays—it’s equally possible that these potentially transformative initiatives could get kicked down the road.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Adverse selection is evidently no myth where longevity insurance is concerned. Variable and fixed indexed annuities “with living benefit features exhibit much lower mortality than those without,” according Ruark Consulting, the actuarial consulting firm.

Ruark has released its 2018 studies of variable annuity (VA) and fixed indexed annuity (FIA) industry mortality. Highlights include:

The studies are based on experience from twenty-seven companies from 2008 through 2017, and over $1 trillion of current account values.

“We have 60% more data than our last studies, allowing for high credibility even when splitting results by multiple factors of influence,” said Timothy Paris, Ruark’s CEO. “Moreover, we now have a lot more experience after the end of the surrender charge and bonus periods, commonly 7-10 years.

“As a result, these studies provide new and important insights into long-term annuity mortality, which should help issuing companies to refine their product designs, pricing, and risk management for these widely-used retirement savings and income products, particularly with pending changes to regulatory requirements,” he added.

Detailed study results, including company-level analytics and customized behavioral assumption models calibrated to the study data, are available for purchase by participating companies.

Ruark Consulting, LLC, located in Simsbury, CT, establishes industry benchmarks for principles-based insurance data analytics and risk management. It studies longevity, policyholder behavior, product guarantees, and reinsurance. Ruark collaborates with the Goldenson Center for Actuarial Research at the University of Connecticut.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Principal Financial Group has hired Sri Reddy, CFA, as its new senior vice president in Retirement and Income Solutions (RIS), effective September 4, 2018. Reddy will Principal’s annuities, full service payout and Principal Bank businesses. He succeeds Jerry Patterson, who now oversees the Full Service Retirement and Individual Investor businesses for RIS. Reddy will report to Nora Everett, president of RIS.

Reddy was previously the senior vice president and head of Full Service Investments for Prudential Retirement where he was responsible for the investments and retirement income businesses. Reddy also led Prudential Bank & Trust and Prudential Retirement’s registered investment advisor (Global Portfolio Strategies, Inc.).

Previously, he held senior leadership positions with USAA and ING. Reddy is a graduate of Baylor University and the Thunderbird School of Business Management. He also serves as a United States Department of Labor ERISA Advisory Council member.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Advocates of legislative proposals that would allow the creation of so-called PEPs—pooled employer plans—say that these provider-sponsored, multiple employer plans will encourage more small employers to offer 401(k) plans.

PEPs will accomplish that in several ways, they say: Above all, by removing most or even all of the legal liability that reportedly scares so many employers away from sponsoring federally-regulated plans; by reducing their administrative chores; and by reducing the notoriously high costs of offering a micro-size plan to the low costs enjoyed by participants in “jumbo” plans.

But, on that last point: it hasn’t been proven that PEPs would in fact save small company owners and employees a lot, relative to the cost of other available retirement plan options. “Small employers will get the benefits of scale, but joining a PEP won’t cut their costs in half,” Pete Swisher, national sales director at Pentegra Retirement Services and author of 401(k) Fiduciary Governance, told RIJ recently.

“The raw cost of providing a plan isn’t dramatically cheaper in the multiple-employer plan. It might take the cost of setting up a 401(k) from a $6,000 thing and turn it into a $5,500 or a $5,000 thing. But it’s not going to turn it into a $1,000 thing,” Swisher added;

Certain parts of the retirement industry are pushing hard for changes in pension law that would allow providers to sponsor PEPs and invite employers to join. Such arrangements, if widespread, could alter the economics and dynamics of the 401(k) business. Large providers could aggregate the assets of many small plans into pools large enough for them to serve economically. The providers might also offer financial wellness programs to participants in many small plans.

Through wellness programs, they could market emergency spending accounts, health care savings accounts, college savings plans, student debt management services, and perhaps even annuities. At a time when the actual costs of recordkeeping and investment options are falling (to near-zero, in the index fund business), large providers need new markets, a broader array of products, and a chance to capture IRA rollovers when employees leave plans or retire.

“Our strategy is to expand the footprint around the broader issue of financial wellness,” Harry Dalessio, head of Full Service Solutions at Prudential, told RIJ in an interview.

In this sixth installment of our series on MEPs and PEPs, we asked 401(k) experts if multiple employer plans would in fact bring lower costs to small employers and small-plan participants. There was no brief or easy answer. On the one-hand, small employers who currently offer high-cost plans could see lower costs in a pooled plan.

It’s true that many small companies still have high-cost plans with expensive investment options that financial advisors sold them long ago. But streamlined, low-cost, low-maintenance 401(k) plans are readily available to small employers today. And some suggest that the cost of keeping records for a dozen or more different small employers could be more complex and therefore more expensive than keeping records for a single plan.

Raw cost of a plan

“The assumption is that multiple employer plans must be about scale and cost-savings, but that’s not what they have to be about,” Swisher said. “We already have an example of a scaled-cost model with Vanguard. Vanguard went to Ascensus to be its recordkeeper for small plans, and they set up a couple of thousand plans a year. Ascensus offers a discount for that. Ascensus was already inexpensive and it became 5% or 10% less expensive. But that in itself is not transformative.

“If that’s all it was about, you don’t need a MEP for to achieve that. The base cost of that work, not the price but the cost, is $4,000 to $6,000. If you’re a micro-business, you don’t want to write a $4,000 check, or even a $2,000 check. A MEP will help with the effort, and a little bit with the cost,” he told RIJ.

“Everybody seems to think that you can divide that $4,000 by 100 and bring it down to $40. No, you can’t,” he said. “There are practical and legal obstacles. Each employer has to have compliance tests done individually, non-discrimination tests. These are tests that have to be done employer by employer. Each employer will have payroll costs. And there are problems that come with processing the different payrolls.”

MEPs “won’t lend themselves to being the cheapest solution [for employers who want to offer a retirement plan to employees]” he added, because they will be monitored by professional fiduciaries who will make sure that the job is done in the best possible way, not in the cheapest possible way.

Jack Towarnicky, executive director of the Plan Sponsor Council of America, agrees.

“A PEP’s small size and its significant flexibility would not necessarily reduce costs, introduce economies of scale/value add, nor lower fiduciary exposure – given the number of small employers in a PEP plan, the different payroll schedules and frequencies which complicate processing, the ability of each participating employer to select a diverse set of investments from a fund lineup – all coupled with numerous other differences in plan design and administration,” he told RIJ.

A veteran in the PEO plan space (PEO stands for professional employer organization, or employee-leasing company) told RIJ that it’s not necessarily cheap and easy to run a multiple employer plan if the companies in the plan don’t use the same payroll firm.

“We benefit from great efficiency in the PEO space because we get a single payroll feed from dozens or hundreds of companies,” said Justin Young, marketing director at Slavic401k. “But I still have to deal with thousands of individual companies on plan setup, contribution remittance, and processing and payroll issues. Someone will have to crack the code, otherwise recordkeepers will have to charge a lot more to run an open MEP.”

Slavic401k charges its clients a combination of asset-based and per capita fees, he said. It charges $39 per year per participant, plus a tiered asset-based fee that goes down as the adopting employer’s plan grows in assets.

A refuge for the asset-based fee model?

“For recordkeepers, it won’t be easy,” said Eric Droblyen, president and CEO of Employee Fiduciary, a third-party administrator of small 401(k) plans whose business could be threatened by the spread of MEPs.

“You have vesting, reconciliation to a single trust. You could have hundreds of different employers. My company could offer a multiple employer plan, but why would we? You’re not going to buy better investments. If you’re looking at plans priced on an asset basis, then yes, it’s a way to drive down costs. But that’s only if you’re married to the asset-based pricing model. Assets have almost nothing to do with the expenses of a 401(k) provider.”

Droblyen called open MEPs “the last gasp of asset-based pricing.” To him, they may make sense to large asset managers, but only in a world where larger pools of assets translate into larger revenues. He believes the 401(k) world must evolve toward per capita pricing, because it doesn’t place a disproportionate portion of the plan costs on participants with large accounts.

“You might have a 10-participant plan where one employee’s account is worth $10,000 and the company owner’s account is worth $1 million. The recordkeeping is just as difficult for one as the other. But with asset-based pricing, participants with high account balances are getting rolled.”

Others agree. “Honestly, if you’re paying 50 basis points (0.50%) for recordkeeping and you have $1,000 in your plan and your fee is $5 and I have a million in the plan and I pay $5,000, that is not equitable. Sooner than later the industry as a whole will have that epiphany and we’ll make a massive move to per capita pricing,” said Justin Young of Slavic401k.

“Guideline, for instance, charges $8 per participant and that’s charged to employer, it’s an all index lineup, and 8 basis points for the investments,” he added. “We look at that and say that’s extremely aggressive. But if were really in this for the best interest of the participant, that’s the best thing for the participants. But that would be hard pill to swallow [for plan recordkeepers and asset managers].”

Absence of a mandate

Pete Swisher believes that the private 401(k) industry has all the tools needed to bring 401(k) plans to small companies, and doesn’t believe that the federal or state governments need to sponsor umbrella plans, he does believe that a government mandate requiring all but the smallest employers to offer plans to employees might be necessary if the country hopes to reach universal 401(k) coverage.

“If there is a genuine need and the market has failed to meet it, then you have a prima facie case for government intervention,” Swisher said. “We don’t have a market failure so much as an absence of motivation. There are structures today whereby small employers could have plans. What’s missing is the cause for them to get out and do it. “It’s the absence of a mandate that’s the problem, not the absence of a product. The state programs will give a governmental stamp to stuff that’s already out there. I think public options will offer competition, I think people will still want help from advisors… that’s been the industry belief from early… the upshot is that the government will probably capture just a small part of the business. I’m not a doom-and-gloomer. If anything, I’m a take a glass three-quarters-full view.”

James Holland, of MillenniuM Investment and Retirement Advisors in Charlotte, NC, agreed that legislation alone won’t ensure that all American workers have a retirement plan. “The big push behind this is based on the idea is that if we just change the rules, somehow it will fix the problem. That doesn’t address the many employers who are unengaged or apathetic,” he said.

“You can lead people to water, and even give them a cup, but that doesn’t mean they will drink from it. I’m not anti-MEP guy by any stretch of the imagination, but this [legislative] proposal is far from a magical elixir. You can’t legislate this problem away. It as to be solved by the people involved—the plan sponsors, the advisors and the participants.”

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Many people in the retirement industry are talking about open multiple employer plans these days, and the concept of a “Retiree MEP” was shared at a retirement policy forum called “Modernizing the U.S. Retirement System, which the American Academy of Actuaries (AAA) sponsored at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. last week.

“The idea builds on the open multiple employer retirement plan (“open MEP”) concept, which many people think has a good chance of passing Congress with next iteration of tax reform,” AAA Senior Pension Fellow Ted Goldman told RIJ in an interview after the event.

In Goldman’s vision of the future, a non-profit organization might sponsor an open MEP and invite companies to transition participant accounts in their existing 401(k) plans to the new plan. Within this MEP would exist a guidance platform–the Retiree MEP–where participants could receive objective information about retirement saving and distribution.

“Instead of putting the employer in the middle of it,” Goldman said, the platform might provide, for instance, an annuity-screening tool to help participants find the best contracts, or a service that would help employees choose an asset management firm or a managed account service.

The platform might also include the capability to help near-retirees decide whether to take a structured withdrawal from their account in retirement, or whether to buy a deferred income annuity (such as Qualified Longevity Annuity Contract). Models for such service platforms already exist at closed multiple employer plans, he said, such as the National Rural Electric Cooperative, Goldman said.

Attendees at the invitation-only forum represented congressional offices, government agencies, nonprofit organizations including the Academy, and academia. In addition to Goldman, speakers and panelists included:

Social Security Administration Chief Actuary Steve Goss, who framed how the current and future benefits provided by Social Security fit in the bigger retirement income picture, and described Social Security’s financial condition.

Major themes of discussion included:

A position statement published by the Academy in fall 2017, “Retirement Income Options in Employer-Sponsored Defined Contribution Plans,” illustrates how actuarial principles can potentially be applied for improved lifetime income outcomes in a retirement system that has largely shifted to defined-contribution plans.

The American Academy of Actuaries is a 19,000-member professional association for the U.S. actuarial profession. It assists public policymakers with objective expertise and actuarial advice on risk and financial security issues. The Academy also sets qualification, practice, and professionalism standards for actuaries in the U.S.

More information about the Academy’s work on retirement policy issues can be found at actuary.org under the “Public Policy” tab.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Though only a few lobbyists, policy wonks and 401(k) insiders appear to fully recognize it, the defined contribution industry is approaching an historical inflection point.

If Congress passes certain proposed bills, employers could be relieved of most of the legal, administrative and financial burdens of choosing and maintaining 401(k) plans for their employees. Plan service providers and outside fiduciaries would assume roles traditionally belonging to employers.

By allowing many employers to join a single plan, these changes have subtle but powerful implications—with the potential to create new winners, losers and any number of unintended and unforeseeable consequences.

These points were made clear during an hour-long webcast this week sponsored by the LIMRA Secure Retirement Institute. In the webcast, entitled “Closing the Coverage Gap,” Ben Norquist, CEO of Convergent Retirement Plan Solutions, described the likely future of 401(k).

Ben Norquist

“There are three factors that we think are converging and are likely to transform the industry” in the next two to four years and which will help “move the needle” in terms of expanding plan adoption by small employers, Norquist said. These factors are:

Norquist recommended that existing retirement service providers follow these trends closely. He advised them to evaluate their own strengths and weaknesses; fine-tune their marketing messages; assess their vulnerabilities; build, buy or partner for necessary new capabilities; capitalize on the opportunities that will inevitably arise.

This was a timely webinar. Today, employers are like the general contractors of their retirement plans. They may not run the plans. But legal responsibility for the major decisions about a plan—what the investment options will be, how much employees will pay for the plan, whether there will be an employer match, and whether to have a plan at all—falls on them, even if they aren’t aware of it.

As such, they are the gatekeepers and guardians of their employees’ retirement savings. It’s a sacred trust. But it has also imposed a burden that many small employers aren’t willing or able to bear. Employer-centric plan sponsorship is seen by some as a bottleneck and a barrier to the universal adoption of tax-deferred workplace savings plans.

The new laws would mean that employers could stop sponsoring plans. Instead industry service providers would sponsor plans and employers would decide whether or not to join them. Others see it as a business disruption or even a threat. It amounts to a deregulation of 401(k)s, which scares some and elates others.

Others, especially large recordkeepers, see it as an opportunity. Legislators are backing the changes in the belief that they will help bring workplace savings plans to tens of millions of workers at small companies and avert an impending retirement income crisis in the U.S.

RIJ is following the progress of the legislative proposals. We think you should too.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.