Year after year, and most eagerly at Easter time, Americans consume millions of yellow marshmallow chicks called Peeps. The spongy hatchlings, along with movie-concession staples like Mike & Ike and Hot Tamales, are manufactured in Bethlehem, PA, by Just Born, a century-old candy company.

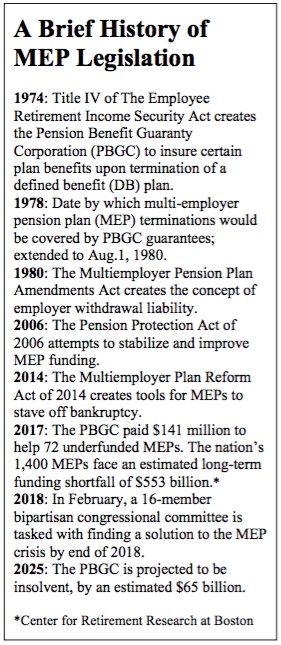

Just Born recently became known for more than just neon-hued snacks. The firm is in litigation with the multi-employer pension plan (MEP) to which it and scores of similar companies contribute on behalf of their workers. The outcome of the lawsuit could help determine the future of the MEP concept.

All sides agree on the facts in the case. In 2012, Just Born and its workers’ union, the Bakery & Confectionery Union, signed a collective bargaining agreement (CBA) in which Just Born agreed to contribute to the union’s MEP for every worker who helped produce candy in its factories. The CBA would run until February 28, 2015.

Later in 2012, Hostess Brands, the makers of Twinkies and the biggest member of Just Born’s MEP, declared bankruptcy and stopped contributing to the pension fund. That threw the fund into “critical” underfunded status. To address the problem, the pension trustees created a new contribution program, to which Born agreed.

In 2015, when the CBA expired, Just Born’s owners announced that it wanted to make a change. During negotiations over a new contract, it told the union that it would continue to contribute to the pension for existing workers but would enroll all new production employees in a 401(k) plan instead of in the pension.

Just Born simply hoped to do what countless single-employer defined benefit (DB) plan sponsors have done—switch from DB to defined contribution (DC) plans and shrink their benefits burden. But the candymaker belongs to a MEP. Labor law lays specific responsibilities on the member companies in a MEP when one member—Hostess, in this case—withdraws from it.

Unilaterally deciding to switch to DC for new hires isn’t allowed. So when Just Born declared “any new [CBA] relieves it from the obligation to make contributions to the Fund on behalf of newly hired employees” and stopped doing so, the pension fund and its trustees sued and Just Born workers (briefly, in 2016) walked out.

The Just Born story is about a specific MEP crisis within a national MEP crisis. Overall, there are 1,296 MEPs in the US serving about 211,000 employers, 3.8 million active participants and 3.66 million retirees and beneficiaries, according to the National Coordinating Committee for Multiemployer Plans.

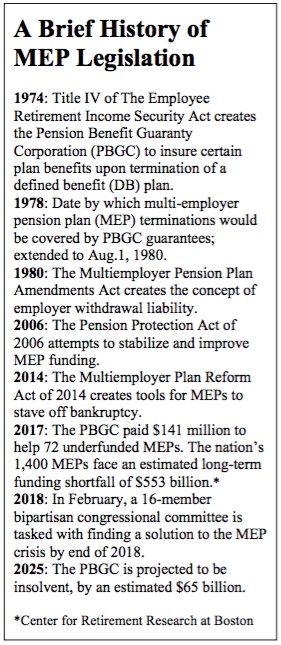

Of those plans, 311 were in “critical” (and collectively $187 billion underfunded) or “critical and declining” ($76 billion underfunded) status in 2015, according to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Whitepapers and special reports about the MEP crisis appeared last year, and this February, Congress appointed a blue-ribbon committee to come up with a plan for getting MEPs out of the red. Exactly how productive talks between union-dominated MEPs and a conservative, business-oriented Congress will be remains unclear.

$60 million exit penalty

Just Born wants to do the unprecedented. As Judge James Wynn of the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals told Just Born’s lawyer during a January 24 hearing: “You found a neat way to get away from the withdrawal penalty. Basically you got rid of it in a circular way that nobody has ever done. You would be the first to do such a thing as this.”

The question is whether an employer in a MEP can segment its workforce and not enroll new workers in the plan without withdrawing from the plan. Just Born doesn’t want to exit the underfunded plan; that would force it to pay a withdrawal penalty based on its share of plan’s unfunded liability. Just Born’s share, as reported by the Washington Post, would be about $60 million.

If Just Born successfully defends its move, other companies could follow suit and MEP plans, already in crisis generally (see below), would be in deeper trouble. So far, Just Born has not been successful. In early 2017, a Maryland federal district judge ruled in favor of the Bakery & Confectionery Union.

“Defendant seems to be trying to walk the line between… two sections of ERISA [Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974], avoiding the contributions required under Plaintiffs’ rehabilitation plan schedules while simultaneously avoiding… withdrawal liability by removing itself from the Fund by attrition, making each new hire an effective withdrawal without acknowledging withdrawal in a way that would trigger the withdrawal penalty,” wrote District Court Judge Deborah Chasanow.

“Allowing an employer to avoid both payments would run contrary to the aim of the two statutes ‘to protect beneficiaries of multiemployer pension plans by keeping such plans adequately funded,’” she added. Just Born, represented by David Rivkin of the Washington, D.C., law firm of Baker Hostetler, then appealed the decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit.

Last January 24, a three-judge panel consisting of Judges James A. Wynn, a 2010 Obama appointee, G. Steven Agee and Stephanie D. Thacker heard oral arguments from Rivkin and from Julia Penny Clark, an experienced labor law litigator with the firm of Bredhoff & Kaiser in Washington.

Rivkin (left), who served as the lead outside counsel in the multi-state suit to nullify the Affordable Care Act, aka “Obamacare, argued that, regardless of the law, it makes no sense to handcuff employers to sinking pension plans. “If you make it too onerous for an employer [to modify a plan], nobody would join ERISA plans in the first place. If you make it too onerous, they’re going to go bankrupt. This [law] is not a cash cow.”

Rivkin (left), who served as the lead outside counsel in the multi-state suit to nullify the Affordable Care Act, aka “Obamacare, argued that, regardless of the law, it makes no sense to handcuff employers to sinking pension plans. “If you make it too onerous for an employer [to modify a plan], nobody would join ERISA plans in the first place. If you make it too onerous, they’re going to go bankrupt. This [law] is not a cash cow.”

‘Hotel California’

Invoking the Eagles’ melancholy hit song, Rivkin asserted that, if Just Born’s flexible interpretation of the law were disallowed, “You’re talking about a ‘Hotel California’ approach. Once you join, you can never leave. Employers don’t have to join these funds, and if they knew it was going to be a Hotel California situation, they would never sponsor a pension fund.”

The attorney for the baker’s union argued the law. “There’s nothing in the statute that says, ‘But wait, if you haven’t yet hired somebody suddenly they are treated differently, and you don’t have an obligation to them,” Clark (right) said.  “[The law doesn’t say] That anyone who comes in and works in that job is covered by the obligation to contribute, but anybody who hasn’t yet walked in is now outside of my contribution obligation and I’m not a bargaining party with respect to them.”

“[The law doesn’t say] That anyone who comes in and works in that job is covered by the obligation to contribute, but anybody who hasn’t yet walked in is now outside of my contribution obligation and I’m not a bargaining party with respect to them.”

Experts on MEPs told RIJ that the law is fairly clear in this case. “Under ERISA, as amended by the Pension Protection Act, certain rules apply when plan is in critical status. Included is a prohibition against restriction of eligibility,” said Richard Perry, a New York attorney at the law firm of Jackson Lewis who represents employers in such cases.

The withdrawal penalty, he added, isn’t necessarily as onerous as it may look. “The penalty doesn’t have to be paid in a lump sum and the real number may be significantly less than that,” Perry told RIJ. “There’s a calculation of the annual payment amount based on historical contributions. It’s paid in annual installments that are generally limited to 20 years.” If paid in a lump sum, might be the present value of those 20 payments.

“The usual issue is: ‘We can’t afford this and we want to get out in general.’ And if you withdraw from a MEP, you pay a withdrawal penalty,” said Josh Gotbaum, who was CEO of the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation from 2010 to 2014. “Just Born’s issue is not the usual issue. Their argument is, ‘We’re not withdrawing because were leaving employees in the plan.’ If they win that argument, then other unions will also think about letting new employees go into a 401(k) plan.”

If Just Born weren’t in a MEP, this wouldn’t be a big deal, Gotbaum told RIJ this week. “Just Born is just trying to do what companies with single-employer plans in the private sector do. In that world, this is not a revolutionary act.” But it’s a big deal in the Taft-Hartley world, he added, where “people are already nervous because the withdrawal penalty in Taft-Hartley cases doesn’t cover all of the withdrawal liability. The penalty understates the obligation.”

‘Messed up’ policy

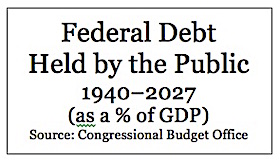

All of this is happening in the context of a larger crisis in the MEP world and the pension world generally. As former Social Security trustee Charles Blahous recently wrote, “Underfunding of U.S. multiemployer pension plans has reached roughly half a trillion dollars… PBGC is only obligated to backstop a portion of these pensions’ benefit promises, [but] even those obligations are estimated to put PBGC $65 billion in the red.” Legislation that might resolve the MEP problem surfaced in mid-February when Phil Roe (R-TN) and Dan Norcross (D-NJ) introduced the GROW Act. It proposed European-style DB/DC hybrids that would provide variable, non-guaranteed pensions to union participants. Unions could maintain a pension-like benefit for their members but employers would no longer be liable for pension underfunding.

Unions are split on the GROW Act, however, with the Building Trades Unions in favor and the Teamsters opposed. Skopos Labs, a New York forecasting firm, gives the bill only a 9% chance of passing. Meanwhile, the Retirement Enhancement & Savings Act, which would have created “open” MEPs was left out of the recent omnibus appropriations bill.

This year, a 16-member congressional committee will try to come up with a new solution to the MEP mess. But, given the general discord in Washington, and the entrenchment of so many competing interests, pensions seem almost beyond repair. Those who understand the issues best are deeply frustrated. As former PBGC chair Gotbaum put it, “We have so messed up retirement policy that we can’t think about sensible ideas.”

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Romine returns to JNLD after serving as the president and chief executive officer of National Planning Holdings, Inc., Jackson’s affiliated independent broker-dealer network that was sold to LPL Financial (LPL) in August 2017.

Romine returns to JNLD after serving as the president and chief executive officer of National Planning Holdings, Inc., Jackson’s affiliated independent broker-dealer network that was sold to LPL Financial (LPL) in August 2017.

A relevant deadline is looming. Minimum contributions to NEST will rise to 5% this month and to 8% in April 2019, effectively locking more consumer earnings into a pension fund. If participants think these increases are unaffordable or don’t want to tie up their money in this way, they might drop out of NEST (National Employment Savings Trust).

A relevant deadline is looming. Minimum contributions to NEST will rise to 5% this month and to 8% in April 2019, effectively locking more consumer earnings into a pension fund. If participants think these increases are unaffordable or don’t want to tie up their money in this way, they might drop out of NEST (National Employment Savings Trust).

Rivkin (left), who served as the lead outside counsel in the multi-state suit to nullify the Affordable Care Act, aka “Obamacare, argued that, regardless of the law, it makes no sense to handcuff employers to sinking pension plans. “If you make it too onerous for an employer [to modify a plan], nobody would join ERISA plans in the first place. If you make it too onerous, they’re going to go bankrupt. This [law] is not a cash cow.”

Rivkin (left), who served as the lead outside counsel in the multi-state suit to nullify the Affordable Care Act, aka “Obamacare, argued that, regardless of the law, it makes no sense to handcuff employers to sinking pension plans. “If you make it too onerous for an employer [to modify a plan], nobody would join ERISA plans in the first place. If you make it too onerous, they’re going to go bankrupt. This [law] is not a cash cow.” “[The law doesn’t say] That anyone who comes in and works in that job is covered by the obligation to contribute, but anybody who hasn’t yet walked in is now outside of my contribution obligation and I’m not a bargaining party with respect to them.”

“[The law doesn’t say] That anyone who comes in and works in that job is covered by the obligation to contribute, but anybody who hasn’t yet walked in is now outside of my contribution obligation and I’m not a bargaining party with respect to them.”