Retirement income aficionados have been studying two fresh ideas for reducing the cost of retirement: Tontines and longevity insurance. Both concepts are active ingredients in the LIFE (Lifetime Income for the Elderly) idea recently proposed by Canadian economist Bonnie-Jeanne MacDonald.

MacDonald, who was a guest speaker at the Defined Contribution Institutional Investors Association Conference in New York last fall, described LIFE in an essay published in January by the Toronto-based C.D. Howe Institute, which is dedicated to “economically sound” public policies that can raise living standards.

LIFE would involve a collective, government-run but professionally managed investment fund. At age 65, people could invest part of their retirement savings in an investment pool. Twenty years later, at age 85, they would begin receiving an income for life. Each person’s income would be based on their contribution, the mortality rates of the pool’s members, and the pool’s earnings.

Though MacDonald doesn’t necessarily call it that, LIFE is a tontine, in which participants bear both all of the investment and longevity risk. No life insurer provides a guarantee, and there’s the rub. Life insurers, seeing a threat, might lobby against it. Free-marketers will oppose anything that’s government-run. And if the funds aren’t liquid, a lot of people might not participate.

But if private companies don’t act, governments may need to create some sort of affordable old-old-age insurance. A public, late-life tontine would cost less (and presumably sell faster) than advisor-sold annuities. It could lighten the potential burden on taxpayers of caring for the very old. For retirees, it would reduce the need to hoard savings against the risk of living too long.

‘Three ideas came together’

In 2009, MacDonald began researching the question of salary replacement rates. That led her to conclude that the long-standing rule of thumb about income replacement rates in retirement—70% of final salary—doesn’t apply to everybody. (Her presentation to DCIAA last fall was on that topic.) Then she began looking at methods of spending savings in retirement.

“I found out that people don’t want to buy annuities from financial service companies. The insurance companies themselves realize the risk of people living longer than expected, and have changed their pricing to account for it. I talked to Keith Ambachtsheer [the Canadian pension expert, emeritus professor at the University of Toronto, and now pension consultant].

“Eventually three ideas started to come together,” she said. “The tontine is one part of it. It’s the ‘pooled risk’ side,” she said. “Then there’s the nationalized aspect, and then the deferred income aspect. It’s those three things together. There are no fixed fees or generational risk transfer,” where a younger generation has to cover a shortfall in saving by an older generation.

All three concepts would in theory lower the individual and social costs of longevity insurance. A tontine is basically an annuity whose payout is determined entirely by the returns of an investment pool and the death rate of the investors. Because it’s not guaranteed, it requires no life insurer to issue it. So it doesn’t involve the expensive hedging, reserves, actuarial work that are sine qua non for guarantees, or the profit requirements that private companies require.

Reducing costs

MacDonald hasn’t worked out all the details of the LIFE program, but she has created an outline for it. “If you throw in too much detail [at this point], people will say, ‘It’s too complicated.’ She put the idea out there at a level that’s readable and understandable,” Ambachtsheer (left) told RIJ.

But, to keep costs down, the product would be intentionally simple. A one-size-fits-all approach makes for less flexibility, but she thinks uniformity will help reduce marketing costs and lack of liquidity riders will raise payouts. Collective funds would provide economies of scale that would reduce investment costs.

No more than two funds. “Originally I said, Let’s just have one fund. It would be volatile, and fluctuate with the markets,” MacDonald said. “There are ways you can do that and still smooth the outcomes at the personal level. Or you could have two funds, a risky fund and a safe fund. Someone might go into the program at age 65. Starting at age 65, and each year afterward, one-twentieth of their assets would move to the low-risk fund.”

A tight window for signing up. “There would be a single contribution and a window in which to contribute. You don’t want people delaying the decision indefinitely. That would make it really complicated. People who would have bought it at 65 might not buy it later, as their health changes. That’s my concern. The decision would be simple.”

Fixed income plus a bonus. “The monthly income would be fixed across their remaining life, calculated using conservative investment and mortality expectations. At the end of each year, any surplus in the mortality experience of the group and investment return on the accounts would be distributed equitably among the age 85+ members through lump sum ‘bonus’ payouts.”

No withdrawals, refunds or death benefits. “The problem with a private industry solution is that they would want to add options [to broaden the appeal and increase sales]. But adding options tends to lead to decision overload. I know that death benefits are popular in deferred income annuities, but the death benefit also makes the solution more expensive. Without the death benefit, people are paying a lot less for their income. It’s more like pure insurance.”

“A [insurer-issued] life annuity gets nicked for a whole lot of things,” Ambachtsheer said. “You have adverse selection issues; you have return on capital issues. If you can get rid of those layers, then you can get more money out the back end. But it’s a great idea on its own merits.”

Resonance overseas

Tontines may sound exotic, but plan sponsors, governments and pension consulting firms in the UK and Europe are currently studying the concept of distributing regular, stable but non-guaranteed income from a collective investment fund as a compromise between defined benefit plans (which put sponsors at high longevity risk) and US-style defined contribution plans (which put participants at high longevity risk).

Per Linnemann, a former chief actuary of Denmark, has developed a product, called iTDFs, based on an algorithm that would smooth the variable payouts from individual accounts within a collectively-managed investment pool. As an option in an employer-sponsored plan, iTDFs would offer a seamless transition from accumulation to decumulation.

Unlike MacDonald’s LIFE product, which offers no liquidity at all during the deferral period, Linnemann’s model would allow individuals to access the money in their accounts during retirement.

“The iTDFs framework can also provide solutions where it is possible for the retiree to maintain flexibility and control of the all of the savings from age 65 to age 84 combined seamlessly with a longevity-pooling phase from age 85,” Linnemann (left) told RIJ.

Pros and cons

There are pros and cons to a program like LIFE. On the plus side: Any advanced-life deferred income annuity (DIA), including those currently issued by about a dozen insurers in the US, prevents hoarding of savings, simplifies the retirement income planning process to a finite block of years (say, 65 to 85), and creates a reserve against long-term care costs.

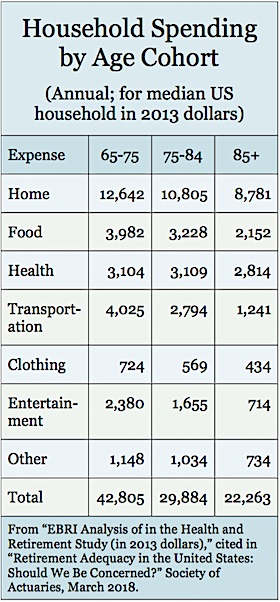

On the anti-hoarding effect, Ambachtsheer said, “Why not create certainty at the back end so that you don’t have people withdrawing as little as possible during retirement just in case they might need the money later.” Perhaps counter-intuitively, retirees spend more [between the ages of 65 and 85] if they parked 20% of their savings in a deferring income annuity.

A national DIA could also help take some pressure off of public service providers (and taxpayers). “Each province in Canada has its own long-term care program,” said MacDonald. “People who think deeply about these things realize that we’ll have a huge elderly population (over age 85) in the provinces going forward and this is going to be very expensive from a health care cost perspective.” The same holds true for Medicaid in the US.

But should government run a tontine? Moshe Milevsky (left), the York University finance professor and acknowledged tontine expert questioned the LIFE program on at least two counts: government control and lack of detail.

“On the one hand, I’m delighted to see yet another credible author and study arguing in favor of introducing a retirement income tontine scheme in Canada—even if she doesn’t call it a tontine,” he told RIJ in an email. “I’m in favor of anything that generates dialogue and interest in this important space.

“That said, her article doesn’t really have any actuarial, financial or pricing information, which makes it hard to evaluate to a quant like myself. I was hoping and expecting to see more details, even if it was relegated to an appendix.”

Milevsky, who has published two recent books on the history of tontines, is not ready to take it on faith that tontines would be cheaper than annuities. “From a consumer perspective, how would the payout compare to annuity payouts? Really, the Devil is in the detail—which is missing,” he said. [For Milevsky’s latest comparison of annuity and tontine payout rates, see [the article] in today’s issue of RIJ.

“I would also like to play Devil’s advocate and ask: Why Government?,” he said. “Why set-up a new entity and potential bureaucracy for this? And if government is getting involved, why not expand the Canadian Pension Plan (CPP, similar to US Social Security) and allow Canadians to buy additional annuity income at retirement? Why not encourage and make it easier for private insurance companies to offer them instead?”

Ambachtsheer suggests that insurers have purposely gone in another direction—toward complexity. “I have gone to the insurance industry and asked them, ‘Why don’t you jump on this idea?’ People are not buying life annuities anyway. To me, part of the problem is this convolution with life annuities where they are part investment product and part longevity product. You’re better off separating the two.”

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

My second question, a difficult one to craft politely, was, in effect: Who is Dean McClelland (at left, beardless), and why should people invest in his company, or, as mere participants in the tontine, trust him with their retirement savings? He’s not, for instance, the kind of recent Ivy League (or Stanford) graduate that private equity firms seem to love tossing money at. He had no special answer, except to shrug almost imperceptibly and say that he’d been an investment banker.

My second question, a difficult one to craft politely, was, in effect: Who is Dean McClelland (at left, beardless), and why should people invest in his company, or, as mere participants in the tontine, trust him with their retirement savings? He’s not, for instance, the kind of recent Ivy League (or Stanford) graduate that private equity firms seem to love tossing money at. He had no special answer, except to shrug almost imperceptibly and say that he’d been an investment banker.

The four versions of the ETF are the Innovator S&P 500 Buffer, the Innovator S&P 500 Enhance and Buffer, the Innovator S&P 500 Power Buffer, and the Innovator S&P 500 Ultra. The caps on upside potential haven’t been declared, and won’t be until the start of one of the funds’ one-year “outcome periods.” Here’s a brief description of each ETF:

The four versions of the ETF are the Innovator S&P 500 Buffer, the Innovator S&P 500 Enhance and Buffer, the Innovator S&P 500 Power Buffer, and the Innovator S&P 500 Ultra. The caps on upside potential haven’t been declared, and won’t be until the start of one of the funds’ one-year “outcome periods.” Here’s a brief description of each ETF: