Total annuity sales were $105.8 billion in the first half of 2017, a 10% decline compared with the first six months of 2016, according to LIMRA Secure Retirement Institute’s Second Quarter 2017 U.S. Retail Annuity Sales Survey.

First half sales have not been this low since 2001. Regulatory uncertainty over sales of the most widely sold annuities—variable and indexed—has added to slump. In contrast to trends of the past, the rising equities and low interest rates are not contributing to sales in those categories, respectively.

In the second quarter, total annuity sales were $53.9 billion, up slightly from the first quarter but an 8% decline from the year-ago quarter. It was the fifth consecutive quarter of decline in overall annuity sales and the sixth straight quarter in which fixed sales have outperformed VA sales—which hadn’t happened in almost 25 years.

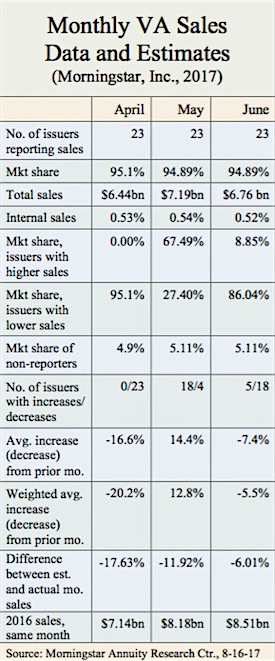

U.S. variable annuity (VA) sales were $24.7 billion in the second quarter, down 8% compared with prior year results. This marks the 14th consecutive quarter of decline in VA sales. Sales from the first half of 2017 VA sales were $49.1 billion—8% lower than the first six months of 2016.

“Qualified VA sales have experienced a more significant decline than non-qualified VAs,” said Todd Giesing, director, Annuity Research, LIMRA Secure Retirement Institute. “VA qualified sales were down 16 percent in the second quarter, while nonqualified sales were actually up 5 percent. This could be in reaction to the DOL fiduciary rule.”

Second quarter qualified VA sales accounted for 58% of retail variable annuity sales, a five-percentage points decline from the same quarter last year.

Sales of fee-based variable annuities increased in the second quarter to $570 million, representing 2.3% of the total VA market. While this is a small portion of the overall VA market, these products have seen continued growth over last year.

Structured variable annuities have also experienced growth. In the second quarter, sales of these products have increased 36 percent, reaching $1.8 billion, which represents 7 percent of the VA market

Institute forecasts VA sales will drop 10-15% in 2017, to less than $100 billion. This has not occurred since 1998.

Fixed annuity sales also declined in the second quarter. Sales were down 7% to $29.2 billion. All fixed product lines sales, except structured settlements, experienced declines. In the first half of 2017, fixed sales fell 11% to $56.7 billion.

Second quarter indexed annuity sales totaled $15.6 billion, a 15% increase from first quarter but are still four percent lower than prior year results. Nine of the top 10 companies have reported quarter-over-quarter growth. The Institute predicts indexed annuity sales will decline 5-10 percent in 2017.

Fixed rate deferred annuities (Book Value and MVA) sales dropped 11 percent in the second quarter to $9.3 billion. Year-to-date, fixed rate deferred annuity sales were $19.4 billion, 14% lower compared to 2016 results.

In the second quarter, deferred income annuity (DIA) and single premium income annuity (SPIA) sales both experienced declines. DIA sales were down 31 percent to just $600 million. SPIAs were down to $2.2 billion in the second quarter—a 12 percent drop.

The second quarter 2017 Annuities Industry Estimates can be found in LIMRA’s Data Bank. To view variable, fixed and total annuity sales over the past 10 years, please visit Annuity Sales 2007-2016. To view the top twenty rankings of total, variable and fixed annuity writers for second quarter 2017, please visit Second Quarter 2017 Annuity Rankings.

To view the top twenty rankings of only fixed annuity writers for second quarter 2017, please visit Second Quarter 2017 Fixed Annuity Rankings. LIMRA Secure Retirement Institute’s Second Quarter U.S. Individual Annuities Sales Survey represents data from 97 percent of the market.

© 2017 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.