What is the nature of insurance advice—in the context of annuities and retirement? Does it mean reading prospectuses? Does it mean recommending an indexed annuity over a bond fund? Can an insurance agent charge for giving investment advice? Can a financial adviser charge for giving insurance advice?

Questions like these, which have specific financial and legal implications, have occupied Michelle Richter for much of her 20-year career in financial services. She contended with them while helping bring insurance products to market at New York Life. More recently, she dealt with them while counseling annuity industry clients at Milliman, the actuarial consulting firm.

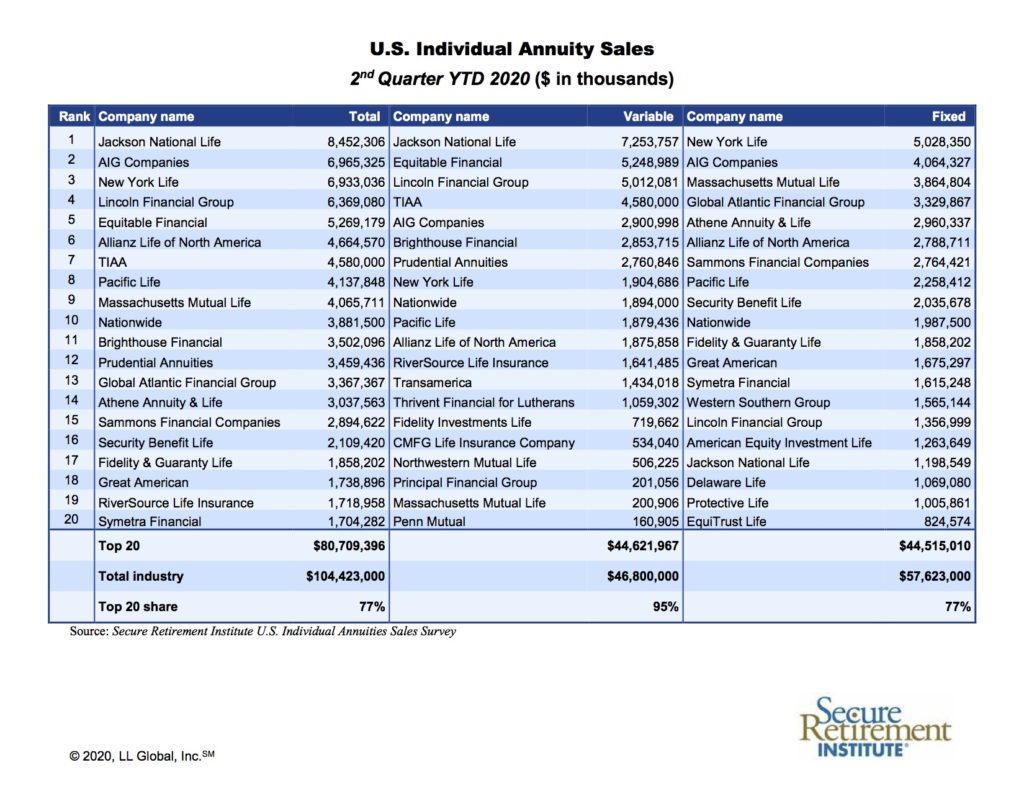

Such questions have become more pressing, and more specific, as the worlds of insurance and investment increasingly overlap, and as life insurers try to normalize the use of their products by the fee-based advisers who serve as the gatekeepers to individual retirees and participants in 401(k) plans.

Life/annuity companies, she believes, have trapped themselves, lobster-like, in growth-inhibiting exoskeletons called products. To evolve, they need to think more in terms of producing investment/insurance hybrids. Recognizing that life insurers need help with this existential challenge, and believing that her real-world experience—and her MBA from Columbia—qualifies her to provide it, Richter recently set up her own consulting firm, Fiduciary Insurance Services, LLC, and begun working with corporate clients.

Michelle Richter

“What made me start this business,” Richter told RIJ, “was the realization that there can be no such thing as a valuable product in insurance” because insurance products are too expensive to manufacture and distribute, and too easy to copy. “That’s why we have seen few new ideas in insurance in decades,” she blogged recently.

“My long-term vision is to keep the industry relevant by changing the focus from products to solutions. I want to help those advisers who are not insurance experts, and those insurance experts who are not investment product experts, to develop programmatic intellectual frameworks that intelligently weave together products for systematic solutions to common consumer challenges,” Richter wrote.

Cannex, the premier annuity rate provider, has collaborated with Richter and supports her mission. “Michelle’s understanding of the practical challenges of implementing systems is invaluable; it’s one thing to devise a new product, but making sure that it is functional and fits within a firm’s compliance framework is another,” Cannex’s Tamiko Toland told RIJ. “She pushes back against the standard perception that this is an industry of followers by devising and facilitating forward-thinking concepts.”

Plenty of ideas

Abstract questions aside, what “systematic solutions” does Richter envision? It turns out that industry participants or academics have floated most of them over the past two decades. But they haven’t been implemented yet, which is where she sees opportunity. Here are examples of the programs she’d like to see finally brought to fruition:

A tontine for qualified plans. It could be structured as an Open MEP (Multiple Employer Plan) offered by a PPP (Pooled Plan Provider) under the 2019 SECURE Act, with a single Form 5500 for all companies in the plan. The program could be modeled on the tontine developed by Nuova Longevita founder Richard Fullmer, a former target date fund manager at T. Rowe Price.

A QLAC-and-SWP combo for qualified plans. (Institutional market) A qualified longevity annuity contract would be purchased and held in a defined contribution managed account (or part of a model portfolio) that also generates income through systematic withdrawals from investments. A portion of the employer’s matching contribution could be applied to the purchase of a multi-premium QLAC that would start producing income anytime after age 72 but by age 85.

Embedding life insurance into personal financial plans. Life insurance agents with securities licenses, especially those who hope to become fee-based registered investment advisers (RIAs) when they have enough assets under management, could use applied software to evaluate the ideal timing and amount of life insurance for a retail non-qualified client.

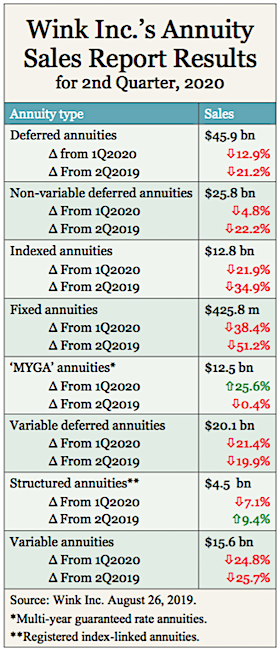

Registered index-linked annuities (RILA) with long-term care insurance for individuals. This program would apply the Cannex Adaptive Withdrawal Strategy, which calculates mortality-based withdrawals from an investment portfolio, this program would apply withdrawals from RILAs (aka structured annuities) in excess of need automatically to the purchase of long-term care insurance.

An income bridge to Social Security for retirees from qualified plans. In this program, a plan recordkeeper and an RIA could help participants create a “bridge” that would give separated employees an income from their plan assets that would support them while they delay claiming Social Security. This would help them optimize the income from their Social Security “annuities.”

Déjà vu all over again

Readers with good memories might recognize some of these programs. In 2008, MetLife and then-Barclays Global Investors teamed up to create SponsorMatch, which applied portions of 401(k) plan contributions to the gradual purchase of a deferred income annuity. During the same period, Financial Engines created “Income Plus,” a managed account program that originally included an optional out-of-plan deferred income annuity.

Tontines have been described in detail by Moshe Milevsky, Jonathan Forman and Fullmer. Over a decade ago, MassMutual created the Retirement Management Account, which used an algorithm to produce a blended income from investments and income annuities for retirees. Before the Great Financial Crisis, actuaries were working on fixed annuities that funded high-deductible long-term care insurance. Academics proposed Social Security bridges over 10 years ago.

Not all of the hybrid insurance/investment ideas have failed. In the 401(k) plan at United Technology Corporation, three life insurers bid to sell lifetime income benefits that participants can wrap around their target date fund savings. DPL Financial, RetireOne, and FIDx have helped RIAs integrate annuities and insurance into their clients’ portfolios, and manage both through a single “portal.”

Life insurers have launched no-load “adviser” versions of their variable and fixed indexed annuities. Software like MoneyGuidePro and eMoney can model annuities. The curricula of certification programs like the Retirement Income Certified Professional at The American College, and the Investment & Wealth Institute’s Retirement Management Advisor both add expertise and professionalism to hybrid insurance/investment advice. Wade Pfau, Ph.D., of The American College, has established an “efficient frontier” for investment/annuity allocations.

So where is the devil-of-a-problem that Richter wants to help solve? It’s still there, in the details. And, despite the successes of the programs described above, they’ve only begun to bridge the chasm between investment and insurance or solve the Boomers’ need for custom retirement income plans.

Lots of unanswered questions remain. What should RIAs charge clients for managing income annuities? How can an RIA know if a new client’s old variable annuity is worth keeping? Will 401(k) annuities be in-plan or out-of-plan, and must they be QDIAs (qualified default investment alternatives) in order to be viable? Have the SEC and Department of Labor resolved what it means to be a “fiduciary”? How does an asset manager retrain an investment adviser to sell annuities? How does a mutual insurance company retrain a career agent to sell investments? How does an RIA justify the choice of a specific fixed indexed annuity contract?

Some of these questions may be unanswerable until there’s a federal insurance authority that mirrors the SEC. As long as “agents” represent companies and “advisers” represent clients, attempts to merge the two roles may create more confusion than clarity (as it does today). But there is pressure to answer these questions soon.

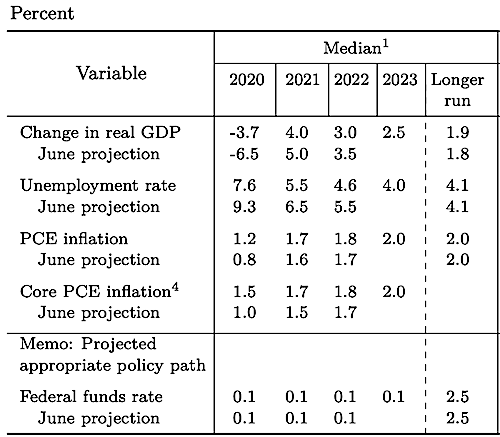

The SECURE Act has created new opportunities for adding optional annuities to 401(k) plans, but it’s not a sure thing. On the negative side, the low interest rate environment threatens the life insurers’ ability to offer guarantees at all. The products they can afford to offer may not be the products that plan participants want.

It’s a truism that most insurance companies are conservative, preferring to be “fast followers” rather than innovators. Today, however, following could be fatal. Richter told RIJ, “Insurance carriers can remain wedded to product sales, which are becoming commoditized in a future that trends toward financial advice, or they can leave their comfort zones and try to move the industry needle toward holistic integrations. I’m betting my career on the second one.”

© 2020 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.