Lincoln launches two new fee-based annuities for RIAs

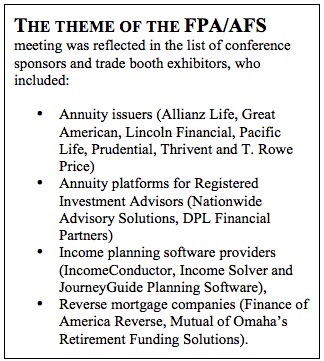

Lincoln Financial Group has introduced two new products for registered investment advisors (RIAs): A single premium immediate annuity (SPIA), Lincoln Insured Income Advisory, and a deferred income annuity, Lincoln Deferred Income Solutions Advisory.

Both are commission-free, allowing fee-based advisers to charge an asset-based fee instead. Lincoln said its annuity sales in the fee-based space have increased more than 150% year-over-year as of June 2019.

Tad Fifer, vice president and head of RIA Annuity Distribution, Lincoln Financial Distributors, said in a release, “We are offering a broad portfolio of solutions for RIAs who choose to include annuities as part of their clients’ retirement plans. Income annuities can help secure life-long or period-certain cash flow with the potential for higher income payout than other available options.”

Over the past year, Lincoln said it has established technology integrations with Orion, eMoney, Envestnet/Tamarac, Redtail and others. These data integrations are designed to make it easier for advisers to incorporate annuities into their clients’ financial planning strategies.

The company also recently implemented a more seamless tax treatment of advisory fees taken from certain non-qualified fee-based annuities. This new treatment affects Lincoln’s fee-based and RIA variable, fixed and indexed variable annuity products (non-SPIA/DIA).

The treatment follows a Private Letter Ruling Lincoln received from the Internal Revenue Service, allowing fee-based advisors to deduct fees related to investment advisory services provided for Lincoln annuity contracts without triggering a taxable event for their clients, assuming certain conditions are met.

Broadridge to buy Fi360

Broadridge Financial Solutions, Inc., a part of the S&P 500 Index, has entered into a purchase agreement to acquire Fi360, Inc. Fi360 is a leading provider of fiduciary-focused software, data and analytics for financial advisors and intermediaries across the retirement and wealth ecosystem.

Fi360 also provides the accreditation and continuing education for the Accredited Investment Fiduciary (AIF) Designation, the leading designation focused on fiduciary responsibility.

The acquisition is expected to close in November. Raymond James & Associates is acting as financial advisor to Fi360 in the transaction. Terms of the transaction were not disclosed.

Broadridge’s acquisition of Fi360 is intended to enhance its existing retirement solutions by providing wealth and retirement advisors with fiduciary tools that complement its Matrix trust and trading platform. The acquisition will also strengthen Broadridge’s data and analytics tools and solutions suite.

“The shift to fee-based advice and imminent regulatory changes, including the SEC’s Regulation Best Interest, are increasing the scrutiny on firms to ensure that they are demonstrating prudent advisory practices,” said Michael Liberatore, head of Broadridge’s Mutual Fund and Retirement Solutions business. “Our goal is to help firms stay ahead of this evolving regulatory landscape.”

Fi360 provides analytical and reporting software that helps investment professionals document investment processes and evaluate products. The software enables broker-dealers to automate compliance procedures and identify at-risk assets.

The company’s online and in-classroom training and ongoing annual designations are designed to help retirement, wealth and other investment professionals serve their clients’ best interests. Fi360 has awarded the AIF Designation to over 11,000 advisors since 2003.

SEC forms Asset Management Advisory Committee

The Securities and Exchange Commission today announced the formation of its Asset Management Advisory Committee.The committee was formed to provide the Commission with diverse perspectives on asset management and related advice and recommendations.

Topics the committee may address include trends and developments affecting investors and market participants, the effects of globalization, and changes in the role of technology and service providers.

The committee is comprised of a group of non-governmental experts, including individuals representing the views of retail and institutional investors, small and large funds, intermediaries, and other market participants.

SEC Chairman Jay Clayton has appointed Edward Bernard, Senior Advisor to T. Rowe Price, as the initial committee Chairman. Other committee members include:

- John Bajkowski, President and Chief Executive Officer, American Association of Individual Investors

- Michelle McCarthy Beck, Chief Risk Officer, TIAA Financial Solutions

- Jane Carten, Director, President, Director, and Portfolio Manager, Saturna Capital

- Scot E. Draeger, President-Elect, General Counsel, and Director of Wealth Management, R.M. Davis Inc.

- Mike Durbin, President, Fidelity Institutional

- Gilbert Garcia, Managing Partner, Garcia Hamilton & Associates

- Paul Greff, Chief Investment Officer, Ohio Public Employees Retirement System

- Rich Hall, Deputy Chief Investment Officer, The University of Texas/Texas A&M Investment Management Co.

- Neesha Hathi, Executive Vice President and Chief Digital Officer, Charles Schwab Corp.

- Adeel Jivraj, Partner, Ernst & Young LLP

- Ryan Ludt, Principal and Global Head of ETF Capital Markets and Broker/Index Relations, Vanguard

- Susan McGee, Board Member, Goldman Sachs BDC Inc.

- Jeffrey Ptak, Head of Global Manager Research, Morningstar Research Services

- Erik Sirri, Professor of Finance, Babson College, and Independent Trustee, Natixis Funds, Loomis Sayles Funds, and Natixis ETFs

- Aye Soe, Managing Director and Global Head of Product Management, S&P Dow Jones Indices

- Ross Stevens, Founder and Chief Executive Officer, Stone Ridge Asset Management

- Rama Subramaniam, Head of Systematic Asset Management, GTS

- John Suydam, Chief Legal Officer, Apollo Global Management

- Mark Tibergien, Managing Director and Chief Executive Officer of Advisor Solutions, BNY Mellon | Pershing

- Russ Wermers, Dean’s Chair in Finance and Chairman of the Finance Department, University of Maryland’s Smith School of Business, and Managing Member, Wermers Consulting LLC

- Alex Glass, Indiana Securities Commissioner (non-voting)

- Tom Selman, Executive Vice President, Regulatory Policy, and Legal Compliance Officer, FINRA (non-voting)

The committee will be formally established on Nov. 1, 2019 for an initial two-year term, which can be renewed by the Commission. The Commission will announce further details about the committee in the near future.

Schwab to offer Pacific Life fee-based investment-only variable annuity

Pacific Odyssey, Pacific Life’s no-commission variable annuity for fee-based advisers who charge clients a percentage of assets under management, is now available to independent Registered Investment Advisors through Schwab Advisor Services.

In addition to the fee charged by their advisers, owners of the contract would pay a 0.30% annual expense ratio on the separate account investments and 0.15% annual mortality and expense risk charge.

The free death benefit promises return of the account value at the contract owner’s death, according to a release from Brian Woolfolk, FSA, MAAA, senior vice president of sales and chief marketing officer for Pacific Life’s Retirement Solutions Division.

Through the Schwab Annuity Concierge Service for Advisors, advisers get free assistance with contract fulfillment from insurance-licensed phone reps, the release said.

Schwab Advisor Services, Charles Schwab Insurance Services and Pacific Life are separate, unaffiliated firms.

Mesirow, Financial Soundings partner on 401(k) managed account service

Mesirow Financial today announced the launch of Mesirow Financial Precision Retirement, a participant managed account program that is designed to enhance financial wellness and offer professional portfolio management for retirement assets.

Mesirow Financial Precision Retirement combines retirement planning advice and reporting, proactive dynamic messaging to achieve targeted outcomes, and Mesirow Financial’s custom portfolio construction expertise, said Michael Annin, Head of Investment Strategies at Mesirow Financial, in a release.

Mesirow Financial partnered with fintech provider Financial Soundings to leverage its proven Retirement Planning Insights program and expand upon the offering to include participant managed account functionality. Financial Soundings has a history of increasing the utilization of employee retirement benefits and improving retirement readiness scoring, said Steve Maschino CEO & President of Financial Soundings

Mesirow Financial Precision Retirement enables plan sponsors to offer online advice based on a participant’s unique situation, the ability to model what-if scenarios, and on-demand reporting.

More investors see a recession approaching: Allianz Life

Fully half of Americans now fear the onset of a major recession, according to the latest Allianz Quarterly Market Perceptions Study. “Consumers are increasingly anxious about the effects of market volatility on their finances,” according to the Q3 findings from Allianz Life.

Increasing numbers of respondents also say they worry that a “big market crash” is “on the horizon” (48% in Q3 compared with 47% in Q2 and 46% in Q1), said Kelly LaVigne, vice president of Advanced Markets, Allianz Life, in a release.

Among Millennials, 56% say they are worried about a recession being right around the corner, compared with 51% of Gen Xers and 46% of boomers. Millennials are twice as likely as Boomers however to say they are “comfortable with market conditions and ready to invest now” (47% of Millennials and just 17% of Boomers).

The share of respondents who say it’s important to have some retirement savings in a financial product that protects from loss has been trending down (66% in Q3 compared with 72% in Q2). But the share of respondents who favored putting some money into a financial product that offers modest growth potential with no potential loss is up (24% in Q3 compared with 18% in Q2).

Fraternals are feeling hazed: AM Best

Companies in the fraternal segment of the U.S. life insurance industry are struggling to stay competitive, given their limited financial resources and difficulties in growing membership, according to a new AM Best report.

The new Best’s Market Segment Report, titled, “U.S. Fraternals Face a Difficult Growth Environment,” said that the segment’s premium growth was relatively flat in 2018 and has been that way for most of the last decade. AM Best believes fraternal insurance companies must embrace newer technologies or risk falling behind.

Net premiums written (NPW) for the 44 U.S. life fraternal companies covered in this report have hovered around $10 billion in each of the past eight years. The fraternal population has tried to compete by guaranteeing higher minimum interest rates on its individual annuity business. But that elevates the fraternals’ risk profiles and pressures operating results.

Still, in 2018 the fraternal segment recorded an 85% increase in net income to $1.6 billion, allowing for consistent growth in the fraternal segment’s capital and surplus, the report said. The segment has extra capacity even though its financial flexibility tends to be limited.

Many fraternals also have broadened their target market to include more religious affiliations or demographic groups. If Millennials become even more socially-conscious and community-focused, the idealism of fraternals may appeal to them. The report notes that AM Best focuses on premium growth, as opposed to membership numbers, as a key component of operating performance.

Consolidation may be more difficult for fraternals, owing to their differing charters. Regarding technology, AM Best foresees that only the largest fraternal societies are likely to be first movers on innovation owing to their limited resources, especially as the insurance industry technology moves toward a world of data analytics and real-time health monitoring devices. Some organizations may enter into run-off, as they struggle to keep up.

© 2019 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.