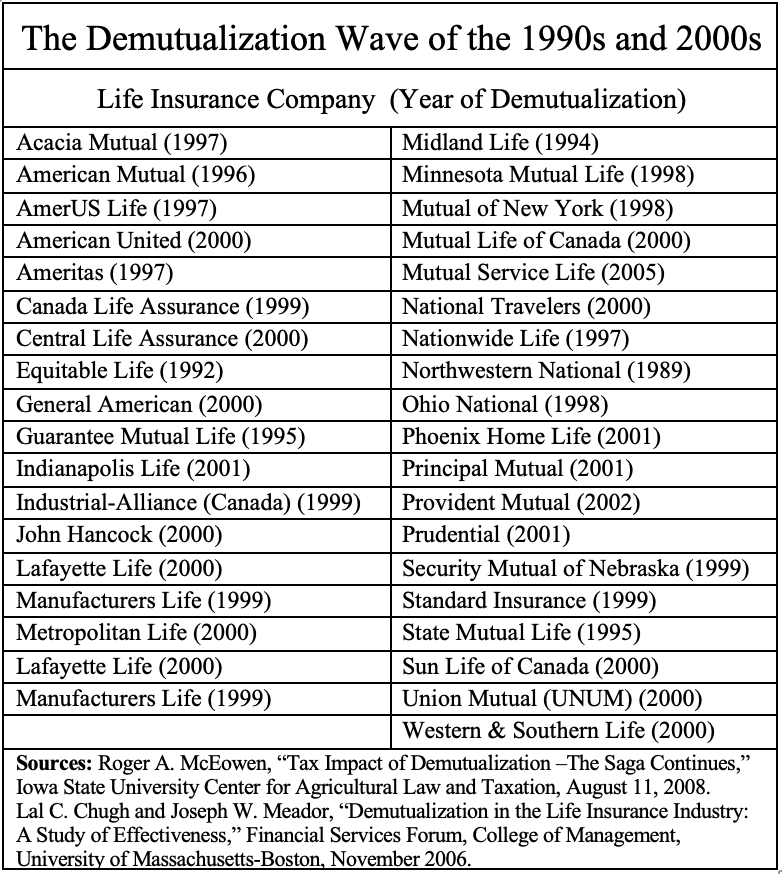

The “demutualization wave” of the late 1990s was a watershed for the U.S. life/annuity business. It was the outcome of forces building up for two decades. It would have profound effects, simultaneously good and bad, on the life/annuity business in the new millennium.

While demutualization was happening, the controversy surrounding it focused on insurance policyholders and whether they would be paid fairly for surrendering their ownership interests in mutual insurance companies. But the companies that went public experienced much bigger changes.

Demutualization gave U.S. life insurers new strengths and new vulnerabilities. They could gobble up other insurers, but they could also be gobbled up. They escaped the tyranny of interest-rate risk but became victims of equity-market volatility. Instead of quiet policyholders, they got noisy, impatient shareholders.

With demutualization, a life insurer goes from being a cooperative aimed at providing its owner-customers with insurance “at cost,” to being a diversified financial corporation aimed at maximizing value for its shareholder-owners. That’s a fundamental change. Demutualization changed the products that stock life/annuity companies sold, how they dealt with financial or biometric risk, their management “styles,” their distribution partners, the regulators they faced, and the accounting regimes they used.

There are infinite numbers of ways to connect historical dots. Causation and correlation can be hard to tell apart. It’s difficult to identify the tipping point that starts a trend until the trend is under way or even over. Today, blessed (or perhaps cursed) with hindsight, we can get a clearer look at the drivers of demutualization (covered in RIJ’s October issue) and its consequences.

The consequences of demutualization

The changes that insurance companies underwent when they demutualized were too subtle for the casual observer to recognize. That was true in part because the changes were already underway at the time of conversion. It was also true because few people had ever understood what happened behind the scenes at life insurers.

Let’s look at a few of the major consequences of demutualization.

From insurance to investments

Coincident with demutualization, the late 1990s saw a “historic shift in life insurers’ overall product mix toward annuities” and away from life insurance sales. (Obersteadt) Although still called life insurance companies, non-mutual insurers and private equity–led life insurers were now primarily annuity companies. (In the U.S., only life insurers can sell annuities.)

After becoming stock companies, life/annuity companies increasingly focused on selling annuities that resembled investments more than insurance and whose returns were correlated more with the stock indices than with interest rates. From 1997 to 2009, non-mutuals focused on sales of variable annuities. Later, their sales focus shifted to index-linked annuities.

Variable annuities are diversified bundles of mutual fund–like investments whose gains aren’t taxed until withdrawn. Fixed indexed annuities (FIAs) and registered index-linked annuities deliver gains only when equity (or hybrid) indexes go up. All are “deferred” annuities; despite their optional income riders, they are used more to generate “protected growth” before retirement rather than to produce lifelong income during retirement.

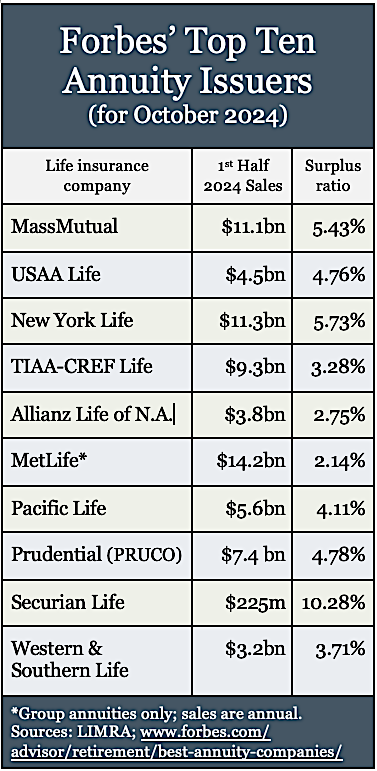

By contrast, mutual life insurers prefer to sell life insurance, deferred fixed rate annuities—whose yields are determined mainly by prevailing interest rates—and either immediate or deferred “income annuities,” whose sole purpose is to provide guaranteed income for life.

“Inflation caused the development of a series of investment products lodged within life insurance companies’ variable life and annuity products. The converting [demutualizing] life insurers are more active in the separate accounts market than the non-converting insurers” and “increase their separate accounts activity significantly after conversion, indicating the possibility that they are able to expand their separate accounts activity once they have access to capital markets.” (Erhemjamts and Leverty)

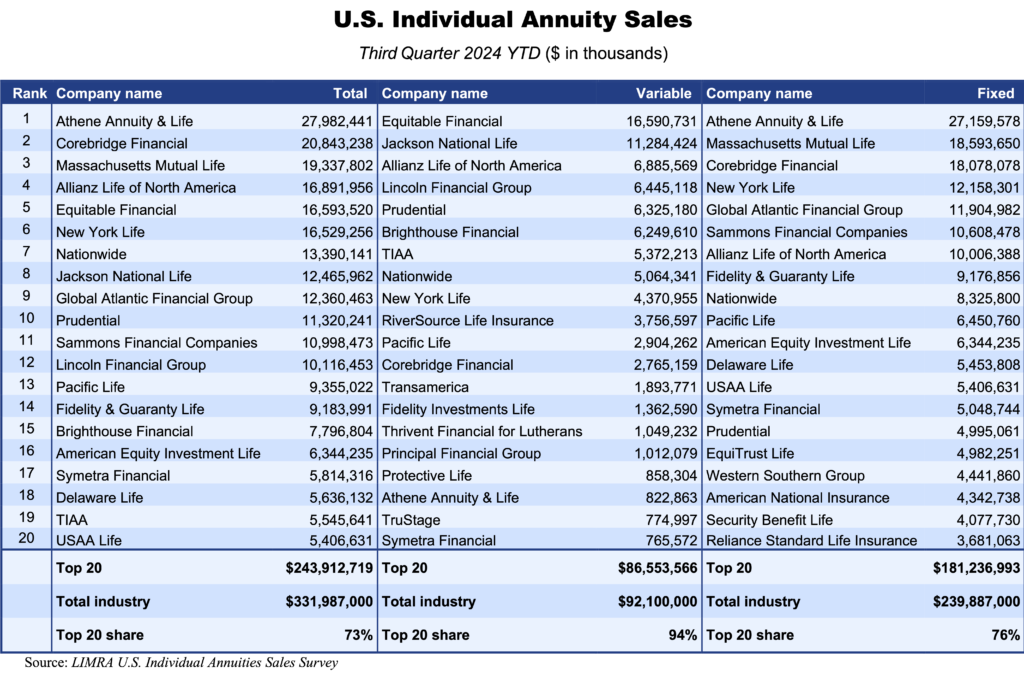

Annuity sales in the U.S. have exceeded life insurance sales every year for at least the past 20 years, according to LIMRA. In 2004, U.S. life insurers sold $183 billion worth of the annuities and $121 billion in life insurance. In 2021, sales tallied $237 billion and $164 billion, respectively. In 2023, according to iii.org, life insurance premiums were roughly one-third of annuity premiums ($121.5 billion vs. $360.7 billion).

Focus on fees rather than “spreads”

Anecdotally, stock analysts prefer financial companies whose income is steady from quarter-to-quarter and throughout the years. Analysts are hesitant to recommend the shares of stock life insurers whose earnings are sensitive to movements in interest rates—which haven’t been steady for decades.

Traditionally, life insurers earned their profits from the spread—the difference between what they earned on their bond portfolios and the interest rate (internal or explicit) return promised to policyholders or contract owners. But deferred variable annuities are long-term products that generate steady asset management fees for fund companies and income rider fees for the life insurer.

When a mutual insurer’s own internal investment management team managed the company’s bond investments and held bonds to maturity, the company enjoyed little or no opportunity to earn asset management fees or trading profits. But large, aggressive, alternative asset managers like Apollo, KKR, Blackstone and Ares now own annuity-issuing life insurers. They can earn high-fee revenues from managing their life insurers’ assets. The asset managers, formerly known as buyout firms, also create customized high-yield debt, bundle and securitize it, and sell tranches of the bundles to various clients around the world—including their own insurers.

From buying “biometric” risk to dealing in investment risk

Life insurers are called life insurers because they employ actuaries who specialize in estimating the life expectancies of individuals and groups. Traditionally they sell protection against dying too soon (i.e., sell life insurance) or against living too long (sell income annuities or annuity riders). Through risk-pooling, asset-liability matching, and buying-and-holding the safest corporate bonds to maturity, they can afford to provide protection from a cluster of investment and biometric risks much more cheaply than the average person’s cost of “self-insuring” against them.

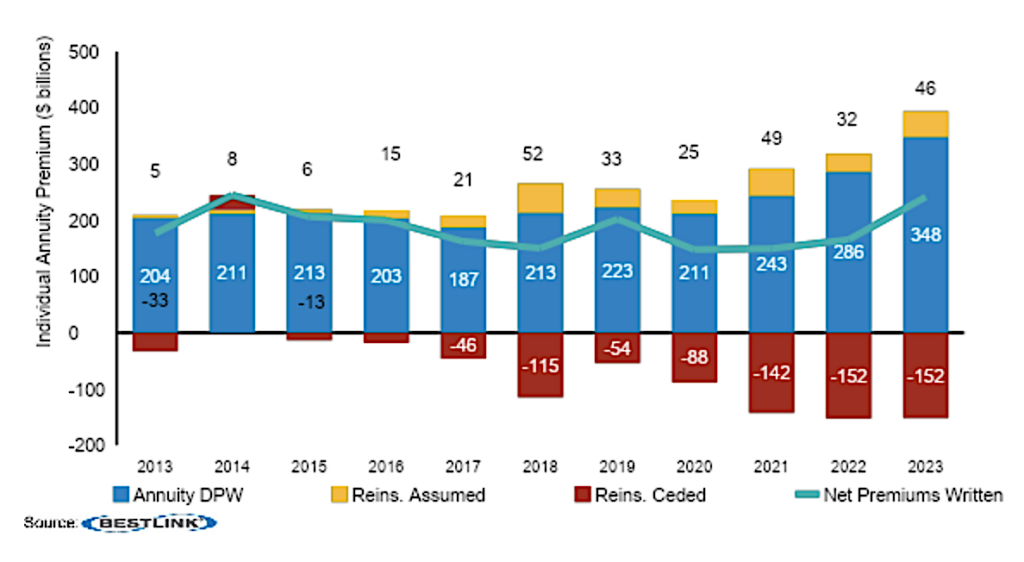

Publicly-traded life/annuity companies have steadily de-emphasized the purchase of biometric risk. Over the years, in fact, they have pulled back from the purchases of any risk. Owners of variable annuities bear virtually all of the volatility risk of their contracts’ account values. Owners of fixed-rate annuities pay surrender fees and market value adjustment fees that eliminate much of the insurers’ interest rate risk. Owners of FIAs bear the opportunity cost of receiving zero yield when the equity indices their contracts are tracking go down during specific crediting periods. They “pass on to the customer the risks and the benefits of the investment management process.” (Friedman)

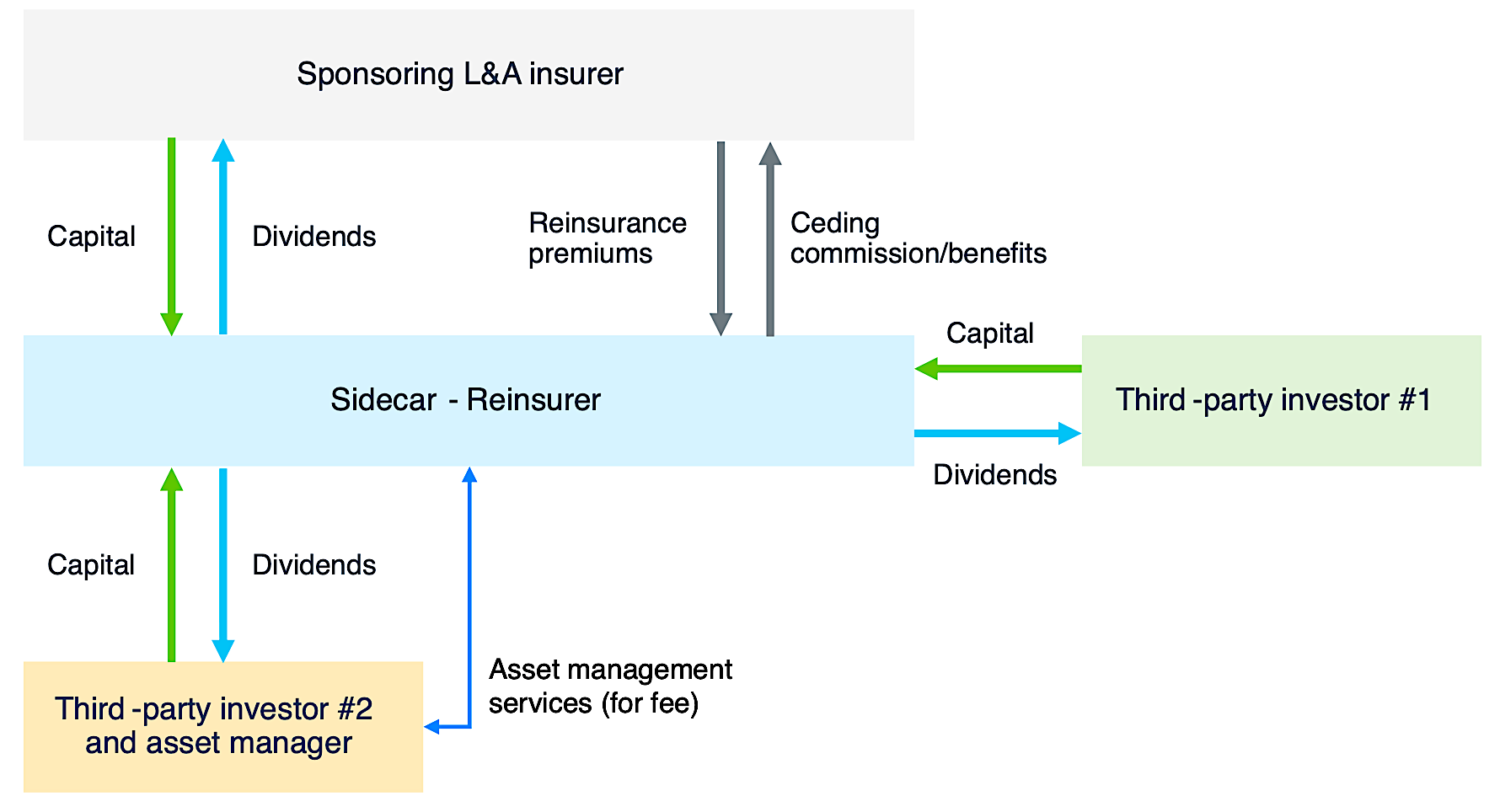

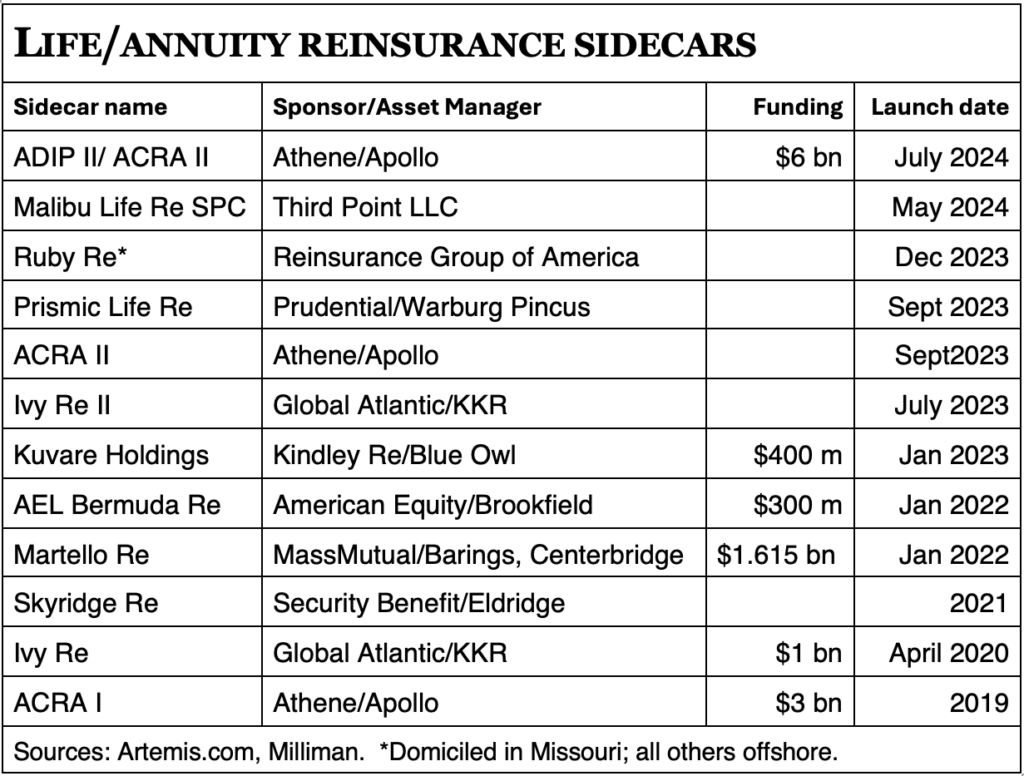

Traditional mutual insurers focus on managing the risk of their liabilities—i.e., the risks of paying large, unanticipated claims—and sometimes buy reinsurance to protect themselves from extreme claims. Publicly-traded life insurers and private equity–controlled life insurers increasingly focus on managing the risks of their assets—i.e., investment risk—and use reinsurance structures to sell their investment risk to institutional investors, such as pension funds and endowments.

From buying public-market bonds to buying securitized private credit

The trillion-dollar asset management firms—also known as private equity firms, buyout firms, and loan originators or alternative asset managers—began creating large numbers of “leveraged loans” for high-risk small and mid-sized companies. Banking regulations (Dodd-Frank) after the Great Financial Crisis made it more costly for bank syndicates to lend to such firms. Wall Street firms filled the vacuum with this private credit.

Highly-rated corporate bonds still account for most of the assets in life insurers’ general accounts, but life insurers, led by the private equity–led insurers, hold increasing amounts of private credit in the form of tranches of bundled and securitized leveraged loans.

These tranches typically have slightly higher yields than corporate bonds with similar credit ratings. Although life insurers do not buy leveraged loans directly—individually they’re too risky—insurers help finance the private credit business when they buy tranches of bundled loans.

Some observers have been worried by the resemblance between these securitizations, known as collateralized loan obligations and the collateralized debt obligations that fueled the over-creation of credit that preceded the Great Financial Crisis.

From career (“captive”) sales forces to independent agents

A mutual life insurance company relies on a different type of sales force to sell its products than a stock life insurance company. Mutual insurers traditionally employ their own dedicated salespeople—known as career or captive agents—who sell only their employer’s products. Captive agents were the sales people who typically sat down with young married couples at their kitchen tables and coaxed them into buying life, home, and retirement products from the same mutual insurance company.

But the process of hiring, training, and retaining such a force—a standing army of salesmen, in a sense—was expensive. When mutual companies became stock companies, many cut costs by either shrinking or eliminating their captive forces. Instead, they engaged individual insurance agents (for fixed annuities) and brokers (for variable annuities) indirectly, through insurance marketing organizations or brokerage firms, respectively.

These wholesaling organizations contracted with, trained, and supervised the people who actually sold the product. They also selected the menu of products that the agents and brokers could sell. The life/annuity companies paid commissions on the sales, with the lion’s share of the commission going to the agent or broker and a smaller portion going to the intermediary organization. Thus they turned a fixed cost into a variable cost that could be built directly into the sale of the product.

“Third-party distribution now represents 52% of sales in life and 81% in annuities. As the competition among insurers in third-party distribution continues to intensify, strategic distribution relationships are becoming closely intertwined with insurers’ success,” according to McKinsey’s January 2024 report, Redefining the Future of Life Insurance and Annuities Distribution.

In handing over the responsibility for managing salespeople, however, life insurers also hand over some of the control. Their reliance on distributors for sales inevitably gives distributors power over them—power to make the annuity manufacturers compete against each other for the agents’ and brokers’ loyalty, which they may once have been able to count on more easily, if not taken for granted.

As a result, “Distributors are demanding more from insurers in the form of personalized bonuses, proprietary products, API integration capabilities, and more. Distribution partnerships also increasingly require insurers to make significant investments in product differentiation, sales incentives, servicing, and technology. These investments can be quite costly to insurers.”

More complex regulation

Demutualization brought more life insurers into clashes with federal regulators. Under the McCarran-Ferguson Act of 1945, life insurers, their products, and the sellers of their products, are regulated by state insurance commissions. But publicly-traded life insurers, like other publicly-traded companies, must report to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and submit new variable annuity products, which include securities, to the agency for approval. Reporting to the SEC is no small burden or expense for life insurers.

As publicly-traded life insurers create more annuities whose performance is tied to the rise or fall of equity indexes (like the S&P 500 Index), there’s ambiguity as to whether these products should be regulated as securities or as insurance products.

Index-linked products with variable returns (RILAs) are regulated by the SEC and sold by brokers, but index-linked products with fixed returns (FIAs) are regulated by 50 different state insurance commissions. In 2007, the SEC tried to regulate FIAs as securities, but failed because the courts ruled that FIA’s no-loss guarantee made them insurance products.

Multiple conflicts of interest

The most subtle but perhaps most significant effect of demutualization may be that it created a conflict of interest between the companies’ shareholders and their customers—the policyholders and contract owners. No one can serve two masters equally at all times.

Insurers are not alone in this. All publicly-traded companies face conflicts of interest to varying degrees. But in the case of mutual life insurers, the fact that policyholders were also dividend-earning owners—they owned “a piece of the Rock,” as Prudential used to boast—created an imperfect but powerful network of loyalty and trust. Shares are much easier to trade away than insurance policies, annuities, jobs, and policyholder rights.

When publicly-traded life insurers became more reliant on commissioned, independent agents and brokers to sell their annuities, the conflict between the clients’ interest and the brokers’ or agents’ interests was added to the mix, creating room for another layer of mistrust between the public and insurance companies.

Bottom line

In the early 2000s, professors at UMass-Boston and Northeastern University studied 11 major U.S. life insurers that fully demutualized (bought out their policyholders with cash or stock) between 1997 and 2001. They found that “demutualization promotes efficiency in the life insurance industry as well as in the capital markets and hence can be viewed as socially desirable.” (Chugh and Meador, 2006)

“Management in these companies has successfully implemented a strategy that is based on higher growth, greater profitability, improved cost efficiency, and innovations in product offerings. These firms take more risk in managing their portfolio assets. The stock form of organization increases transparency in reporting and governance, and provides opportunities for firms to engage in mergers and acquisitions. In addition, the demutualized firms offer new securities for investors and unlock the value lying dormant in the mutual policyholders’ surplus. For these reasons, the long-run market returns of demutualized companies have outperformed various market indexes, including the NASDAQ Insurance Company Index, creating economic value.” (Ibid.)

There’s a case to be made that demutualization has led to a split between life insurers and some of the academics who do retirement research. Academics have written countless books and papers on the benefits to retirees of owning immediate income annuities—the type of annuities that publicly-traded life insurers are least likely to sell. This contributes to confusion in the public’s mind about the value of annuities.

A quarter-century after the stampede, one could argue that demutualization backfired, even as it achieved several of its tactical goals. Though, as stock companies, life insurance companies could use shares as mergers & acquisition currency to acquire other life insurers. They also made themselves into acquisition targets. In that sense, demutualization may have hastened the consolidation of the industry. As stock companies, they also could accept billion-dollar infusions of equity capital from European firms like ING and AXA, only to see that capital take flight after the Great Financial Crisis.

Demutualization clearly made life insurers more vulnerable to financial turbulence. The U.S. stock market crash in 2008 reduced the value of the investments backing the lifetime income guarantees of variable annuities by tens of billions of dollars. It did variable annuity issuers little good that the investments were in separate accounts, under the contract owners’ control, or that the investments were likely to (and did) recover their value long before the issuers would need to pay most of the claims on those guarantees. (Obersteadt)

The market crash created the equivalent of a margin call for life insurers, like The Hartford, which had written those lifetime income guarantees and under-hedged the market risks associated with them. The Hartford, for instance, needed an emergency $15 billion loan from Allianz Life of North America. It later sold its retail annuity business to Goldman Sachs. Meanwhile, insurers that remained mutual, such as New York Life, Guardian, Northwestern Mutual, experienced stress during the 2009–2022 low interest-rate famine but survived.

In retrospect, some life insurers appear to have followed the herd into demutualization without fully understanding the exposures, hazards, shareholder demands, and bad press they would face in the sharp-elbowed world of stocks. It’s not that they weren’t warned.

“Many of the companies that are becoming public are doing so with a general lack of the necessary years of experience that it takes to manage a company optimally on a GAAP basis as a public company”:

-

- “Your financials are open to public scrutiny, and, depending on the situation, they could be scoured and challenged. [The public will be] digging into the numbers and comparing your company to other companies.

- Quarterly financials are required…for a public entity and will be subject to the same level of scrutiny as year-end financials.

- Another consideration is the pressure to maintain growth and profit patterns… When dealing with insurance products, we are dealing with long-tailed liabilities. Many companies with a mutual company perspective have been used to very long-term management time frames. But now, if you are a public company with a publicly traded stock, your income statement has to be very solid and predictable in current periods as well as in long-term trends.

- You should be able to forecast earnings accurately, and you don’t want volatility or negative trends, even if you believe that long-term gains will result. Anything like that would tend to have an adverse effect on your stock price.” (SOA 1999)

Demutualization radically changed the character of many life insurance companies. The differences between stock and mutual companies aren’t just “inside baseball” topics, with relevance to only to quantitative analysts (“quants”), actuaries, securities analysts, and academics.

Consumers of financial products—such as retirees who might be exploring annuities as supplements to their Social Security income—need to understand these distinctions.

Potential purchasers of annuity products should understand the behind-the-scenes sorting process that, depending largely on the business model of the insurer, determines which products they see or don’t see, which type of agent or adviser deals in a particular set of products, which products certain agents or advisers will never show them, and how well they will be served by the insurer, agent or adviser after buying—or not buying—the product.

© 2024 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Sources

Balasubramanian, Ramnath, et al. “Redefining the Future of Life Insurance and Annuities Distribution,” McKinsey & Co., January 2024.

Chugh, Lal, and Meador, Joseph. “Demutualization in the Life Insurance Industry: A Study of Effect.” Financial Services Forum Publications. Fall 11-2006.

Erhemjamts, Otgontsetseg and Leverty, J. Tyler, The Demise of the Mutual Organizational Form: An Investigation of the Life Insurance Industry, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, February 24, 2010. ( https://ssrn.com/abstract=1558536 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1558536)

Friedman, Stephen J. “The U.S. Life Insurance Industry: The Next Five Years,” Pace Law Faculty Publications, January 1990.

“Generally Accepted Accounting Principles: Implications for Mutual Insurance Holding Companies and Demutualizations,” Society of Actuaries, Record, Vol. 25, No. 1, Atlanta Spring Meeting, May 24-25, 1999.

“Mutual Insurance Holding Company Conversions: Lessons Learned,” Society of Actuaries, Record, Vol. 24, No. 1, Maui I Spring Meeting, June 15-17, 1998.

Obersteadt, Anne, et al. “State of the Life Insurance Industry: Implications of Industry Trends,” National Association of Insurance Commissioners and Center for Insurance Policy and Research. August, 2013.

© 2024 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.