Retirement assets total $29.8 trillion in 2Q2019: ICI

Total US retirement assets were $29.8 trillion as of June 30, 2019, up 2.3% from March 31, 2019. Retirement assets accounted for 33% of all household financial assets in the United States at the end of June 2019.

Assets in individual retirement accounts (IRAs) totaled $9.7 trillion at the end of the second quarter of 2019, an increase of 2.9 percent from the end of the first quarter of 2019. Defined contribution (DC) plan assets were $8.4 trillion at the end of the second quarter, up 2.6% from March 31, 2019.

Government defined benefit (DB) plans— including federal, state, and local government plans—held $6.2 trillion in assets as of the end of June 2019, a 0.7 percent increase from the end of March 2019. Private sector DB plans held $3.2 trillion in assets at the end of the second quarter of 2019, and annuity reserves outside of retirement accounts accounted for another $2.2 trillion.

Defined Contribution Plans

Americans held $8.4 trillion in all employer-based DC retirement plans on June 30, 2019, of which $5.8 trillion was held in 401(k) plans. In addition to 401(k) plans, at the end of the second quarter, $545 billion was held in other private-sector DC plans, $1.1 trillion in 403(b) plans, $339 billion in 457 plans, and $617 billion in the Federal Employees Retirement System’s Thrift Savings Plan (TSP). Mutual funds managed $3.8 trillion, or 65%, of assets held in 401(k) plans at the end of June 2019. With $2.2 trillion, equity funds were the most common type of funds held in 401(k) plans, followed by $1.1 trillion in hybrid funds, which include target date funds.

Individual Retirement Accounts

IRAs held $9.7 trillion in assets at the end of the second quarter of 2019. Forty-six percent of IRA assets, or $4.5 trillion, was invested in mutual funds. With $2.5 trillion, equity funds were the most common type of funds held in IRAs, followed by $952 billion in hybrid funds.

As of June 30, 2019, target date mutual fund assets totaled $1.3 trillion, up 4.1% from the end of March 2019. Retirement accounts held the bulk (87%) of target date mutual fund assets, with 68% held through DC plans and 19% held through IRAs.

T. Rowe Price model portfolios offered on Envestnet platform

T. Rowe Price Group, Inc. announced today that its T. Rowe Price Target Allocation Active Series Model Portfolios will now be available to financial advisors through the Envestnet Fund Strategist Portfolio (FSP) and Unified Managed Account (UMA) Programs.

The Target Allocation Active Series on the Envestnet platform consists of seven risk-based asset allocation models designed to meet a wide range of investment objectives. The model portfolios use T. Rowe Price equity and fixed income mutual funds as their underlying investments. The series will be available to advisors and companies leveraging Envestnet’s wealth management platform.

The Target Allocation Active Series is managed by T. Rowe Price Portfolio Managers Charles Shriver, Toby Thompson, Robert Panariello, Guido Stubenrauch, and Andrew Jacobs van Merlen. Each portfolio manager is a member of the T. Rowe Price Multi-Asset team, which had $332.5 billion in assets under management as of June 30, 2019.

27% of Americans very confident about retirement: TIAA

TIAA’s 2019 Lifetime Income Survey found that various uncertainties are key detractors of financial confidence among Americans– with just three-in-ten respondents saying they are very confident they will always feel financially secure, including during retirement.

Only a little more than one-in-three (35%) are very confident they will be able to maintain their lifestyle as long as they live. Uncertainty about the future of social programs and market performance, concerns about unexpected expenses and investment losses, and fear of saving too little are all major detractors of confidence.

The survey showed a number of skills and practices that build confidence. For example, the ability to plan long-term and invest effectively are key drivers of feeling secure. Those who rate highly their ability to invest effectively are roughly three times as likely to express confidence in always being financially secure, including throughout retirement. Long-term planning can also play a role in financial confidence, as those who are able to master this skill are at least twice as likely to feel confident.

U.S. ranks 18th in retirement security

The United States dropped two spots to No. 18 among developed nations on the 2019 Global Retirement Index, released this week by Natixis Investment Managers. The annual index found the U.S. ranked the same or lower in all four sub-indices:

- Health

- Material well-being

- Finances

- Quality of life

Three global risks to long-term sustainability weigh on retirees and policymakers—low interest rates, longer lifespans and the costs of global warming.

The Seventh Annual Natixis Global Retirement Index examines 18 factors that influence retiree welfare, producing a composite score for evaluating comparative retirement security worldwide.

Highlights of the 2019 Global Retirement Index include:

Factors affecting the US GRI ranking

For all four sub-indices, the US ranked the same or lower in this year’s Index compared to last year, including Material Wellbeing (28th from 26th), Finances (10th from 9th), Quality of Life (20th from 19th) and Health (held steady in 10th place). The following are notable factors affecting the US position:

Growing pressure on government resources

The US lost ground in the Finances category, but remains in the top 10. The Index reflects an increasing proportion of retirees to working adults, an ongoing trend that is putting growing pressure on Social Security and Medicare funds.

Rising government debt and tax pressures also contributed to the US’s lower score in the Finances category, which was offset by improvement in interest rates and fewer nonperforming bank loans.

Economic inequality widens

Despite rising employment, the gap between wealthy and poor continues to grow. The US has the eighth-worst score for income equality, even though it has the sixth-highest income per capita score among all GRI countries. These factors generated a lower score for the US in the Material Wellbeing category.

Lower life expectancy despite health spend

The US maintains its position in the top 10 (at 10th) for health due to an improvement in insured health expenditure, which measures the portion of that expenditure paid for by insurance, and by maintaining the highest score globally for per capita health spending. But the US experienced a decline in life expectancy as Americans’ longevity failed to keep pace with that of top-ranked Japan and other nations.

Quality of life in relation to retirement security

A lower score for happiness, which evaluates the quality of retirees’ current lives, weighed on the US’s Quality of Life performance. However, the US continues to achieve the seventh-highest score for air quality on the Index and it showed improvement in its environmental factors indicator score, though not enough to lift it out of the bottom 10 in that category.

Western Europe continues to lead as a region, with 15 countries finishing in the top 25 for the third year in a row. The Nordic countries maintain their strong performance in the top 10, including

Iceland (No. 1)

Norway (No. 3)

Sweden (No. 6)

Denmark (No. 7)

Ireland advanced to No. 4 from No. 14 two years ago due to an improved score in the Health sub-index, where it moves into the top 10 (from 19th), driven primarily by the country’s higher per capita health spending. The country also performed well in Finances, powered by improvements in bank nonperforming loans and government indebtedness.

Japan, which ranks No. 23, stands out for having the lowest score among GRI countries for old-age dependency, a measure of the number of active workers compared to the number of retirees. Japan has the highest life expectancy, but also one of the lowest fertility rates among developed countries.

Three pressing risks for retirement security

The Natixis report, “Global Security. Personal Risks,” supplements the 2019 Index and illustrates three pressing risks and their implications for retirees and future generations globally. The analysis serves to encourage dialogue among policymakers, employers and individuals to understand the impact and help manage the risks to society.

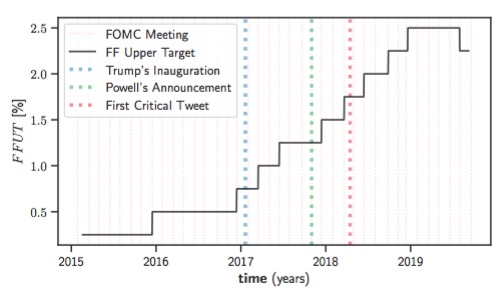

Interest rates: Interest rates do not appear to be rising anytime soon, and the related low yields on investments present hurdles for those looking to generate income in retirement. As a result, retirees may be forced to invest in higher-risk assets, thus exposing their portfolios to greater volatility at an age when they might not have time to recoup losses due to a market downturn. Indeed, more than four in ten Baby Boomers (aged 55–73 years old) in the US surveyed by Natixis earlier this year said they were blindsided by the market downturn in 2018.

Demographics

Longevity represents a key risk for retirees. In the US, the ratio of older adults to working-age adults is climbing. By 2020, there will be about 3.5 working-age adults for each retirement-age person; by 2060, that ratio will fall to just 2.5. This leaves policymakers with hard choices on how to address the funding crunch.

Financial and health impacts of climate change

The risk of climate change is often viewed through a long-term lens, but it poses tangible health and financial risks to today’s retirees. The costs associated with natural disasters help force up insurance rates and consume government resources. Severe events helped make 2018 the fourth-costliest year for insured losses since 1980, according to Munich Reinsurance Co. Extreme heat has increased the risk of illness among older adults, particularly those with chronic illnesses, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency.

Millennials lead emphasis on sustainable investing

The rapidly aging population in the US means a large percentage of people depend on Social Security payments at a rate that threatens the long-term sustainability of the nation’s retirement system. At the same time, younger generations are leading the charge for long-term sustainability, seeking to have a positive impact on the world and, ultimately, their retirement security.

© 2019 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.