To equip a 55-year-old with a fixed index annuity (FIA) so he can flip on an income stream in 10 years isn’t so different from advising him to buy 10-year bonds today and swap them for a life annuity in 10 years.

The FIA is merely built for another kind of customer, another kind of agent or advisor, another financial environment: In short, for today’s near-retiree who is frustrated by low interest rates, nervous about equities, and agreeable to an all-in-one packaged product sold in a vendor-financed transaction.

In this final segment of RIJ’s four-part series on FIAs, we look at the role they can play in a retiree’s financial plan. We can report the obvious: An FIA that produces pension-like income starting 10 years after purchase and lasting for life can reduce both sequence risk and longevity risk.

But for certain people more than others. FIA-loving advisors or agents say that FIAs are the only solution to the retirement puzzle that many clients will accept. Their job, they say—like the job of any retailer who wants satisfied, repeat customers—is to match product with prospect by listening carefully.

“When you have all the facts and client preferences, the puzzle solves itself,” said Bill Borton, a veteran insurance agent and managing principal of W.R. Borton & Associates. Jim Fahey, an Ameriprise counselor in Center Valley, PA, told RIJ, “I could call the FIA a can of beans instead of an annuity and my client would still have said yes. Because it did the job he needed done.”

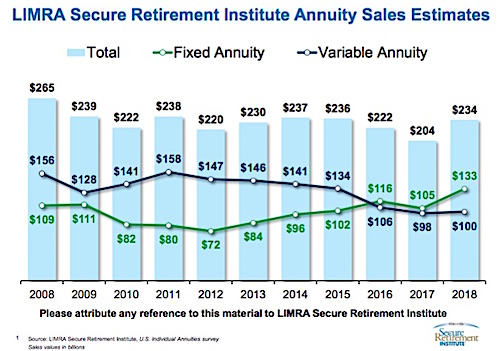

If that makes sense, this statistic may not: Steadily, since the third quarter of 2014—even as the Boomer retirement wave is peaking—the percentage of FIAs sold with income-generating riders has dropped by 40%. But there’s a reason for that, as we’ll see.

Where FIAs fit

The guaranteed lifetime withdrawal benefit rider (GLWB), which about 40% of today’s FIA contracts carry, isn’t usually the academic’s first choice as an income-generator—it’s too complex for their tastes—but it is effective. And people accept it because it produces lifetime income without depriving them of access to their money in an emergency.

Adding a GLWB to a retiree’s portfolio always reduces a retiree’s risk of running out of money: it’s built to do that. For those who need proof, papers by Wade Pfau of The American College and David Blanchett of Morningstar have shown that a retirement income portfolio with almost any kind of income-producing annuity will last longer than one composed solely of stocks and bonds.

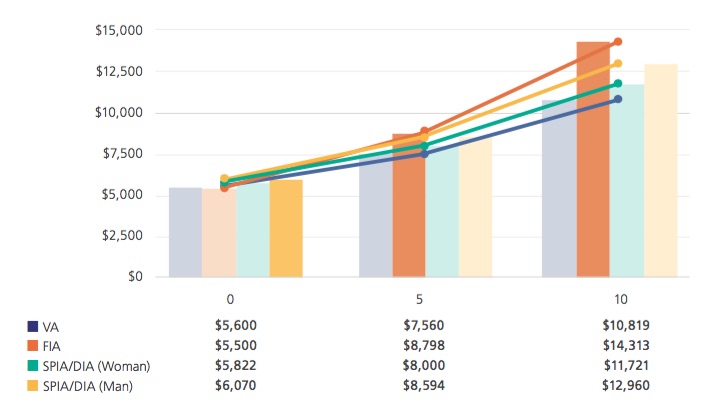

One catch with FIAs is that, to maximize the income from a GLWB rider, you generally have to buy the rider several years before you need the income it will provide. In 2018, CANNEX, the annuity data aggregation and analysis shop, ran a study (click on chart below) comparing the minimum amount of income that FIAs, deferred variable annuities with GLWBs and DIAs (deferred income annuities) could produce starting either immediately, five years or 10 years after purchase.

Looking at the top five products in each category, the CANNEX analysts found that the top FIAs can generate more annual income than the top deferred income annuities or variable annuities with income riders, assuming that all three types of products are tapped for income after a ten-year holding period.

“On the basis of the guarantee alone, the income annuities tend to provide the greatest income for scenarios with immediate income and can also be more valuable for a man. With a delay in income, FIAs often perform best,” the study said.

The five top income-producing product in the CANNEX study, in each category, delivered these guaranteed minimum levels of annual income for a single person at age 65, ten years post-purchase: FIA/GLWB ($14,313), DIA for a man ($12,960), DIA for a woman ($11,721) and VA/GLWB ($10,819). (GLWB pricing is not gender-specific.)

Comparative Product Payout Rates. Source: “Guaranteed Income Across Annuity Products,” Cannex, October 2018.

How can FIA issuers promise to pay out more? Since FIA contracts are not irrevocable and DIA contracts are, FIAs experience higher “lapse rates.” That is, owners frequently—the rate varies from carrier to carrier and product to product, and is not made public—surrender the contracts or, more likely, are persuaded by new advisors to exchange them for something else. Issuers can advertise richer guarantees because they won’t have to make good on as many of them. The high lapse rate also suggests that this product is often hawked to people who later regret the purchase. Asked if this were true, a wirehouse annuity manager told RIJ, “100%.”

What advisors say

One of the advisors we talked to for this story, Bill Borton, specializes in retirement risk management and income planning and hosts a weekly Internet TV show, ‘Live Better, Longer,’” about retirement. “I’ve sold dozens of FIAs and plan to sell a lot more,” he told RIJ. He has a system: he assesses each prospect, uses off-the-shelf software to structure an income plan, and then runs his specs through a product selection tool available through his annuity wholesaler. The tool identifies the best products for the task he describes to it.

Bill Borton

“If somebody wants to put $300,000 into an FIA with an income rider, for example, I may sell three contracts, with the idea that we’ll turn some income on in five years, then seven years, then 10 years, depending on the ages they plan to retire and the years they want to take Social Security,” Borton told RIJ. “You can model all these things and provide income when the client needs it.”

“The income rider is something that Boomers like. They don’t have to give up control of principal. That’s an objection I hear all the time. Rational or not, if the illiquidity of a SPIA stops the income planning conversation entirely, then what good is it? Would you rather be right or happy? The right product is the one that does the job and that the client will buy,” he said.

Another advisor we talked to, Jim Fahey, is a fee-based (paid a percentage of assets under management or by commission) Ameriprise advisor who has increasingly recommended FIAs to clients. In a recent transaction that Fahey described to RIJ, the client didn’t need current income as much as a safe haven from the market. The prospect of receiving a high rate of guaranteed income in extreme old age sealed the deal.

James Fahey

In this case the client was a 67-year-old, who used $200,000 in profits from the market to buy a RiverSource FIA whose rider had a deferral bonus that would double the minimum income benefit base, to $400,000, after 12 years without withdrawals. At age 79, he’d start receiving $26,000 a year for life—income that he could use as a hedge against assisted living expenses, if necessary. (The client can access the benefit base only at the rate of $26,000 a year; only his account value, which may be much lower after years of fees, withdrawals and market volatility, would be accessible as a lump sum.)

Selling that type of FIA, with a rich guarantee of income after a long deferral, to someone with short-term needs would be an embarrassment or worse for a national broker-dealer wealth manager like Fahey. “If I put someone into a long-term index annuity with an income rider and three years after purchase he says, ‘Oh, I need to withdraw 10% of my money,’ I would turn ten shades of crimson,” he said. “But I don’t do that.”

So why aren’t they selling?

But, while overall sales of FIAs are up, fewer Americans every year intend to use them for retirement income and many of those who employ them for income use them inefficiently, according to data that Wink, Inc. shared with RIJ for this report.

In the third quarter of 2014, GLWB riders were elected on 71.6% of the FIAs purchased. A year later, the election rate was down to 50%. In 4Q2018, only 39.6% of FIA contracts sold had an income rider, of which 32.3% had a built-in or mandatory rider and the rest had an optional rider.

When people do buy the rider, they’re probably not maximizing the potential income, Wink data also suggested. The average age for the purchase of an FIA with a GLWB was 64.1 years in 4Q2018, and they started income 2.6 years after purchase, on average. To get the most out of deferral bonuses, they should buy earlier and take income later.

The simple explanation is that FIAs aren’t being marketed for income at present. They’re being marketed for yields that are higher than bonds, fixed-rate annuities or certificates of deposit (CDs). High-volume FIA agents have found that they can attract many more people to a luncheon seminar by advertising high yields. The cost of income riders puts drag on FIA yields. The income story doesn’t just have less sizzle than the yield story; the cost of the income rider undercuts the yield story.

The accumulation focus is tied to the increased use of volatility-controlled “hybrid” indices. Many FIA issuers now offer crediting methods linked to these indices “because they can promote higher participation rates and lower spread rates on them than on crediting methods linked to the S&P500 Index,” said Sheryl Moore, president and CEO at Wink, Inc. “The focus on hybrid indices, and the ‘accumulation sale,’ has reduced GLWB election rates.”

The potential returns on hybrid indices—like the potential payouts on long-shot horses—are higher because their caps are less likely to be reached; their internal volatility controls make sure of that. But the high caps fill seminar seats nonetheless.

What’s always troubled purists is the apparent tendency to emphasize quantity of FIA sales over quality of sales. That tendency is almost certainly strengthened by the fact that the average manufacturer-paid commission on FIA sales is over 6%, or more than double the commission on sales of plain-vanilla income annuities. FIA advocates insist that the compensation is reasonable and fair in the long run, and that the product sells on its merits. FIA avoiders maintain that generous compensation will always be a temptation to predatory sales. Caveat emptor.

© 2019 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

.jpg)

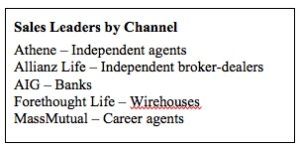

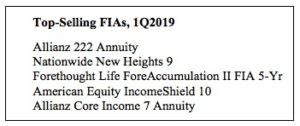

ForeAccumulation II 5-year (the #3 seller overall) was the top seller in the bank and wirehouse channels. The 7-year version of the product was among the top ten best-selling products in both of those channels. The C.M. Life Index Horizons contract, which is issued and distributed by MassMutual was the most popular product in the career agent channel.

ForeAccumulation II 5-year (the #3 seller overall) was the top seller in the bank and wirehouse channels. The 7-year version of the product was among the top ten best-selling products in both of those channels. The C.M. Life Index Horizons contract, which is issued and distributed by MassMutual was the most popular product in the career agent channel.