Ubiquity raising $19 million to finance small plan recordkeeping software

Ubiquity Retirement + Savings, a fintech provider of flat-fee retirement plans to small businesses, is nearing $19 million in Series D funding led by existing investors who have invested in the firm since its beginnings 20 years ago, the company announced this week.

The fresh capital will financed the development of Paradigm RKS, Ubiquity’s proprietary, cloud-based, automated recordkeeping system for the historically underserved small business market. The founder and CEO of San Francisco-based Ubiquity is Chad Parks.

Third-party administrators, recordkeepers and financial institutions serving the small business market will soon be able to license Paradigm on a business process outsourcing (BPO) and Software as a Service (SaaS) basis. It can be useful to providers that lack the infrastructure to serve the small plan market, or have less efficient legacy systems and processes.

Gen-Xers are a lost generation in the workplace: MetLife

The retirement plight of Gen X—a group now ages 38 to 53, who accounts for a third of the U.S. workforce, or 53 million people—has been upstaged by that of Boomers and Millennials, according to MetLife’s 17th Annual U.S. Employee Benefit Trends Study (EBTS).

“The impacts of this neglect are real: Gen X employees not only feel significantly underappreciated at work and engage at lower rates than Millennials, they also lag both Boomers and Millennials in key financial security indicators,” MetLife said in a release.

The research, like other studies of this type, helps make a case for “financial wellness” plans. These optional services, now seen by many big plan recordkeepers as a competitive necessity, typically help employees cope with debt, improve financial literacy, and deal other challenges that might hinder saving for retirement.

According to the survey:

- 59% of Gen X workers are confident in their finances, compared to 67% of Millennials and 65% of boomers, the release said. Only 53% of Gen X workers have at least three months of salary on hand for emergencies, compared to 58% of Millennials and 60% of Boomers.

- 68% of Gen X workers report being happy at work, compared with 75% of Millennials and 74% of Boomers. Only 54% of Gen X workers feel empowered at work and 62% feel respected in the workplace, the MetLife research found.

- More Gen X workers than Millennials believe “employers are not providing timely promotions, exposure to senior leadership, and meaningful work projects,” the survey showed. But only 18% of employers believe it a priority to create an inclusive environment for all generations.

- 18% of Gen X employees do not plan to retire, compared to 14% of Millennials and 12% of boomers. More Gen X workers (55%) are behind on their retirement savings than Millennials (49%).

- When asked to decide between “better benefits or more flexibility,” 57% of Gen X workers chose better benefits such as paid leave, financial wellness programs, legal plans, supplementary health and disability insurance provide resources, compared with 48% of Millennials.

“Eighty percent of all employees want financial wellness programs available to them through work, yet just 20% of employers offer this benefit,” MetLife said.

Roughly two-thirds of Gen X workers say their employers do not provide people management and development skills training or learning opportunities to adapt to technology innovations, yet only 29% of employers consider “up-skilling” current workers.

Engine, a market research firm, conducted MetLife’s 17th Annual U.S. Employee Benefit Trends Study (EBTS) in October 2018. The survey covered companies with at least two employees and included 2,500 interviews with human resource decision makers and influencers and 2,675 interviews with full-time employees, ages 21 and over.

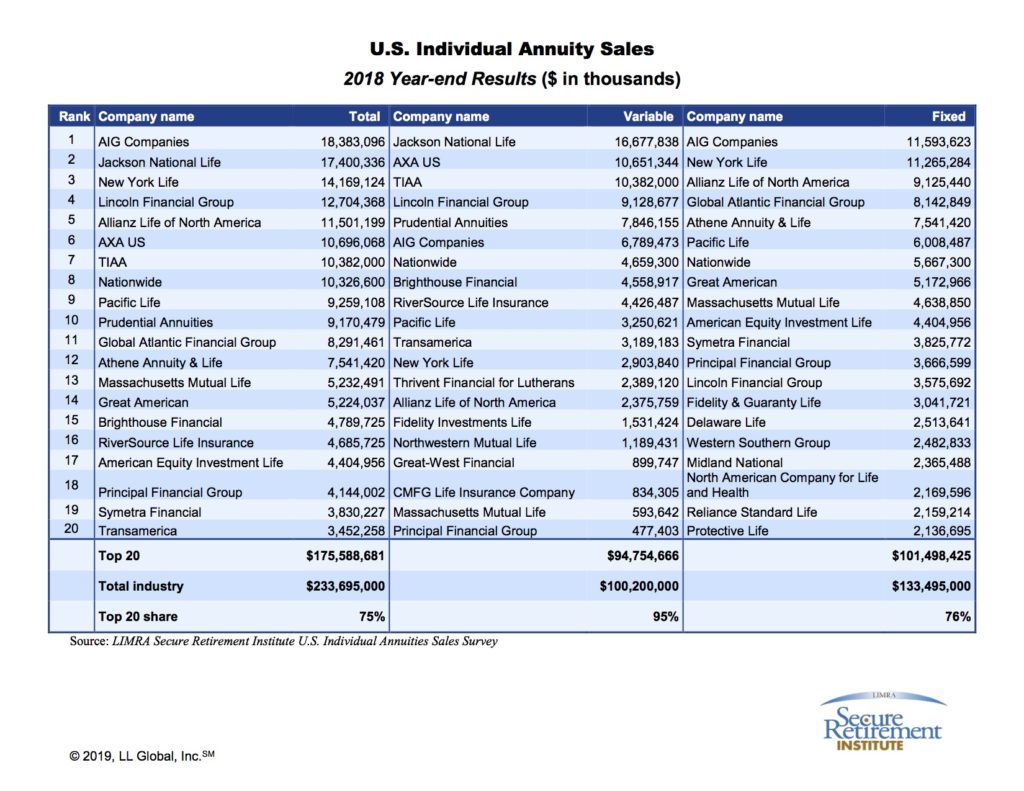

Betsy Palmer takes top communications job at AIG

American International Group has appointed Betsy Palmer has been appointed senior vice president and Chief Marketing Strategy, Communications and Industry Leadership Officer of the insurer’s Life & Retirement division, AIG announced this week.

Palmer will be based in New York, join the Life & Retirement Executive Team, and report to Kevin Hogan, CEO, Life & Retirement. She will lead marketing, communications, stakeholder management, industry thought-leadership, sponsorship and brand positioning activities across Life & Retirement. She will also serve as the Life & Retirement organization’s primary spokesperson.

Palmer joins AIG from TIAA, where she was senior vice president and chief communications officer since 2010. Her previous experience also includes senior marketing and communications roles with EY, BearingPoint and AT&T.

Earlier, Palmer served in communications roles at the U.S. Department of Energy and the White House. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in foreign affairs from the University of Virginia.

New 3.05% fixed income option for retirement plans from Principal

Principal Financial Group has launched the Principal Guaranteed Option (PGO), a new fixed income investment option with a current (March 1 to May 31, 2019) guaranteed crediting rate of 3.05% that will be available to advisors and sponsors of retirement plans.

According a release, PGO offers:

Capital preservation: Seeks to preserve capital and provide a compelling guaranteed credit rate over a full interest rate cycle.

Portability: Customers can maintain interest in PGO even if the plan moves to a new recordkeeper.

Accessibility: Available for 401(k), 401(a)-DC, 403(b) and governmental 457(b) plans.

Guaranteed rates: Crediting rates reset every 6 months.

Solid backing: The guarantees are supported by the multi-billion dollar general account of Principal Life Insurance Company

Rate level flexibility: 14 rate levels available

Regarding rate levels, “As a general account backed guaranteed product, PGO does not have expense ratios,” a Principal spokesperson told RIJ. “The 14 rate levels are available service fee selections that a plan fiduciary can select as part of their overall fee arrangement for the plan to pay for recordkeeping and administrative services provided to the plan.

“The rate level service fee the plan fiduciary selects is deducted from the overall crediting rate for the product, resulting in a net crediting rate that will apply to the plan. For example, the overall crediting rate for the product is 3.05%. If a plan fiduciary elected 0.25% to be deducted to pay for administrative and recordkeeping services to the plan, the resulting net crediting rate for the plan would be 2.8%.”

Principal has developed a new online resource hub for advisors to support their conversations with plan sponsors about fixed income investment options. Features include videos, fact sheets, articles and client-ready materials. Advisors are encouraged to visit principal.com/fixedincome.

MassMutual launches new investment platform for DB plans

MassMutual is launching a “new, expanded and more flexible” investment platform developed with Matrix Financial Solutions, Broadridge company, and designed for defined benefit (DB) pension plans, the mutual life insurer announced.

Financial advisors and plan sponsors can use the platform to access enhanced reporting and on-line functionality, find additional registered investment options, and customize investment offerings, a release said.

The platform is “the latest installment of MassMutual’s longer-term strategy to… support larger pension plans of $200 million or more,” said Michael O’Connor, head of MassMutual’s DB business. MassMutual serves more than 2,600 DB plans totaling more than $20 billion in assets under administration as of Dec. 31, 2018.

The new platform offers self-service reporting capabilities for simplified administration. Sponsors and advisors can generate reports on trusts, measure investment performance against benchmarks, and create custom reports on individual plans.

The company recently launched its PensionSmart Analysis tool, which examines the plan’s current status, funding level, and service structure. MassMutual’s pension experts can then assess the pension plan’s health. MassMutual has also introduced customized pension yield curves to help plan sponsors measure their pension obligations.

Matrix Financial Solutions is a leading provider of TrueOpen retirement products and services for third party administrators, financial advisors, banks and other financial professionals. It servs more than 400 financial institutions with over $300 billion in customer assets processed through its trading platform.

Stephen Grourke to lead fund-raising at The American College

Stephen J. Grourke, CAP, CFRE, has been named as senior vice present for advancement and alumni relations at The American College of Financial Services, effective April 1, 2019, college president and CEO George Nichols III announced this week.

Grourke will lead the Advancement team, charged with raising funds for the college, and will oversee The College’s current $17.5 million fundraising campaign projected to successfully conclude in 2020. Grourke was most recently executive director for the Office of Estate and Gift Planning at Villanova University.

Prior to Villanova, Grourke spent over a decade at The Nature Conservancy, the world’s leading conservation organization, where he served in a variety of capacities around the country, including associate director of philanthropy in Idaho and director of philanthropy operations in Pennsylvania.

Grourke earned a bachelor of arts degree from Gwynedd-Mercy University and a master of public administration from Eastern Washington University. He holds the Chartered Advisor in Philanthropy designation from The American College of Financial Services, and is a Certified Fund Raising Executive.

NFP to acquire Bronfman Rothschild, merge it with Sontag Advisory LLC

NFP Corp., the large insurance broker and consultant and provider of wealth management, retirement and estate planning to high-net-worth individual clients, said it intends to acquire wealth advisory firm Bronfman E.L. Rothschild, LP.

Upon completion of the acquisition, NFP will integrate Bronfman Rothschild with Sontag Advisory LLC (Sontag), its New York-based wealth management subsidiary. Subject to satisfying closing conditions [and receiving regulatory approval], the transaction is expected to close in the second quarter of 2019.

The combined entity will manage about $10 billion for individual and institutional clients. Howard Sontag, chairman of Sontag, will become chairman of the combined entity; Mike LaMena, president and chief operating officer of Bronfman Rothschild, will become chief executive officer; and Eric Sontag will become president and chief operating officer. A new brand strategy for the combined firms will launch later in 2019.

Bronfman Rothschild is an independent Registered Investment Advisor based in Rockville, Maryland, with offices throughout the Midwest and East Coast.

Sontag Advisory, an NFP Corp. subsidiary, is a New York City based, independent registered investment advisory firm that serves clients in more than 30 states. Recently NFP was named the second largest retirement plan aggregator firm, as ranked by Investment News and the fifth largest US-based privately owned broker.

Ascensus continues to expand by acquisition

Ascensus, the retirement plan recordkeeping and administration specialist, has agreed to acquire Wrangle, the Junction City, OR-based provider of health and welfare Form 5500 filing services to employee benefits brokers and plan sponsors. The services include collecting information from carriers, managing schedules and deadlines, and e-filing information with the Department of Labor.

ERISA compliance, plan documentation, filing, and related services have been among Ascensus’ Retirement, Health, and TPA Solutions business segments have historically provided ERISA compliance, plan documentation, filing and related services.

Ascensus expanded its benefit administration offerings in 2018 by acquiring Chard Snyder and Benefit Planning Consultants, Inc., which provide consumer-directed healthcare administration (e.g., health savings accounts, flexible spending accounts, and health reimbursement accounts) and benefit continuation services (e.g., Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act and retiree billing administration).

“Wrangle owns an almost 25% market share in providing health & welfare Form 5500 solutions and has long-standing relationships with the nation’s largest employee benefits brokers,” says Raghav Nandagopal, Ascensus’ executive vice president of corporate development and M&A., in a release.

© 2019 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

.jpg)