Skopos Labs, a Manhattan-based machine-learning firm, gives the Retirement Enhancement and Savings Act (RESA) a 24% shot at approval by the U.S. House of Representatives and an 18% chance of becoming law. The firm also assigns RESA a “significance score” of 7 out of 10: it could shake up the retirement industry.

Eighteen percent is far from a guarantee, especially in these distracted times. But that’s 4.5 times as likely to be enacted as the average bill. RESA has Republican sponsors (a big plus) in both the Senate (where it originated) and the House. The Senate Finance Committee approved it with a 26-0 bipartisan vote in 2016. It was reintroduced in both houses this year.

RESA contains a bunch of provisions intended to promote retirement savings in the US. Topping its wish list is a revision of current pension law to allow a large number of unrelated employers to join a single “pooled employer plan” run by a “pooled plan provider” (PPP).

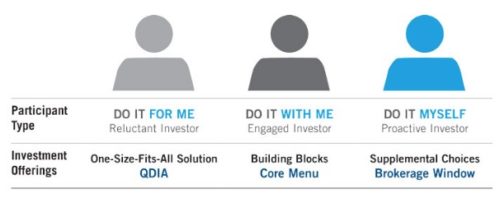

Depending on how you interpret RESA and America’s other pension laws and regulations (embodied by the Employer Retirement Income Security Act of 1974), RESA might allow plan service providers to, in effect, sponsor 401(k) plans and then recruit many small and mid-sized employers to join in what would be a single plan.

Current law doesn’t allow this. To be sure, plan advisors and third-party administrators routinely sell packaged 401(k) plans to small employers. Similarly, firms like Ascensus Betterment offer near-identical plans to many small employers. But, in those cases, each employer sponsors its own plan. RESA could, for the first time, let providers create single plans for multiple employers and their employees.

Would RESA do that? The language of the bill doesn’t explicitly say so. Such vagueness is confusing to 401(k) experts. On its face, the bill encourages small employers to band together to create multiple employer plans and then hire service providers to handle the chores. But there’s no evidence that small employers have lobbied for that.

Indeed, the reverse is more likely. RIJ’s interviews with retirement experts indicate that, if enacted, the bill might allow 401(k) service providers to set up plans and invite small employers to join. This would create economies of scale for both small employers and large providers that are currently absent in the market place–and perhaps lead to broader 401(k) availability in small companies. But, again, the bill doesn’t explicitly enable provider-driven plans.

A close look at RESA

What does RESA say, exactly? Among other things, RESA explicitly:

¶ Creates a new class of defined 401(k) contribution plans or a collection of IRAs called pooled employer plans (PEPs) that uses a pooled plan provider (PPP). “A PEP is to be treated as a single plan where ERISA Section 210(a) applies – a multiple employer plan,” said Jack Towarnicky, executive director of the Plan Sponsor Council of America in an email to RIJ.

¶ Removes the existing “commonality” requirement. In a PEP, the employers could be unrelated. That’s new. “Pooled employer plan does not include a plan with respect to which all the participating employers have both a common interest other than having adopted the plan and control of the plan,” said an official report on RESA in 2016.

¶ Removes the “one bad apple” rule. The acts of one negligent employer couldn’t ruin the PEP for the other participating employers. That too is new. “The provision provides relief from disqualification (or other loss of tax-favored status) of the entire plan merely because one or more participating employers fail to take actions required with respect to the plan,” said the same report.

¶ Allows for simplified reporting and audit relief by employers. A provider could file a single Form 5500 on behalf of all the participating employers. A PEP with fewer than 1,000 participants where no employer had 100 or more participants wouldn’t be subject to DOL audit.

Who can be a plan sponsor?

Does RESA as currently written open the door to industry-sponsored workplace retirement plans–plans in which the employer’s fiduciary role would be limited to choosing and monitoring the providers? The answer seems to be either no or maybe. On the other hand, 401(k) plans, like annuities, are typical sold, not bought. So the question might be semantic or legally moot.

Pete Swisher, national sales manager at Pentegra Retirement Services and author of “401(k) Fiduciary Governance: An Advisor’s Guide,” grapples with this issue in an open letter to clients last month. He wrote:

“There is no evidence [that service providers will be able to sponsor their own PEPs–perhaps this will end up being true, but there is no evidence of it in the Bill. The Bill could have, for example, amended ERISA Sections 3(5) and/or 3(16)(B), the definitions of “employer” and “plan sponsor,” but does not do so.”

In an interview this week, Swisher told RIJ, “If the question is, ‘Can a provider sponsor its own MEP and provide a variety of services to employers?, that’s a difficult construction. There’s nothing in current law and nothing in RESA to permit it,” he said.

“But there is a path there. A service provider could be the provider and the sponsor if an outside party were hired as the independent fiduciary. There’s history there. Someone unrelated to the service provider and drawing no more than 2% to 5% of his income from that business, maybe a law firm, could hire somebody to do that,” Swisher added.

“Then a Vanguard or a Fidelity could be appointed [to run the plan]. But it’s difficult to come up with that construction, and it wouldn’t succeed at the beginning.”

Jack Towarnicky, executive director of the Plan Sponsor Council of America, told RIJ that the RESA removes the “lack of commonality” obstacle that caused the DOL to disapprove of provider-sponsored multiple employer plans—which Towarnicky calls “sponsored MEPs”—in 2012. But it doesn’t eliminate every obstacle.

“A sponsored MEPs is not possible today,” Towarnicky told RIJ in a recent email. “However, I believe the [regulatory] agencies might favorably receive proposals to create a ‘sponsored MEP’ as consistent with DOL interpretive bulletin guidance regarding state-sponsored MEPs.

That bulletin, published in the Federal Register in late 2015, acknowledged the benefits of PEPs that state legislatures might sponsor (as Vermont has done). But the bulletin, written by Phyllis Borzi, head of the DOL’s Employee Benefit Security Administration under President Obama, specifies that state sponsorship fits within current law in a way that provider sponsorship doesn’t.

“In the Department’s view, a state has a unique representational interest in the health and welfare of its citizens that connects it to the in-state employers that choose to participate in the state MEP and their employees, such that the state should be considered to act indirectly in the interest of the participating employers.

“Having this unique nexus distinguishes the state MEP from other business enterprises that underwrite benefits or provide administrative services to several unrelated employers.” But that was then. Borzi’s successor in the Trump DOL is Preston Rutledge, the Senate Finance Committee lawyer who is widely credited with having drafted RESA in 2016 for its initial sponsor, Sen. Orrin Hatch.

Next in our series: The companies that are leading the RESA campaign.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.