If you were to read through the papers on retirement income that were presented at the American Economic Association’s meeting last month in Philadelphia, you’d come away with a good sense of what it takes to accumulate enough money for a secure old age.

You need to do at least three of the following: Stay healthy, work longer, postpone Social Security, take a little more market risk, inherit money from your relatives, or buy an annuity that insures you against the chance that you might live beyond age 85.

Summaries of a few of the retirement-related papers that were presented at the meeting appear below. These papers are based on analyses of data sets such as TIAA participant history, Chilean defined contribution participant data, mathematical modeling of annuity benefits, and U.S. government surveys.

In short, academics continue to validate common sense and to measure what hides in plain sight. In a perfect world, their efforts might be superfluous or redundant. But, in the world we inhabit, relatively few individuals or institutions heed their warnings. So the work goes on.

The value of longevity income annuities as 401(k) defaults

The search for a way to add a retirement income component onto defined contribution (DC) plans started at least 20 years ago, when the decline of defined benefit plans became obvious.

In “Putting the Pension Back in 401(k) Retirement Plans, Optimal versus Default Longevity Income Annuities,” Vanya Horneff, Raimond Maurer and Olivia Mitichell suggest that many U.S. retirees would be much better off if part of their qualified savings were defaulted into a annuity with income delayed until age 80 or 85.

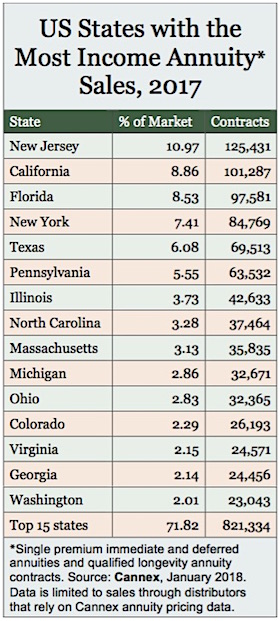

Back in 2014, the U.S. Treasury cleared the way for this innovation by creating qualified longevity annuity contracts, or QLACs. This change in the tax code allows savers to apply up to 25% (or $125,000, if less) of their tax-deferred IRA or 401(k) savings to the purchase of an annuity whose payout could begin anytime between age 71 and age 85.

Prior to the rule, savers could not exclude any portion of their qualified savings when they calculated their annual minimum distributions, which must begin at age 70½. Aside from affecting the RMD rules, the new rule also allows plan sponsors to default participants into QLACs.

The authors of this paper assert that QLACs could improve the lives of many Americans if they were included as default distribution options in qualified plans. At retirement, they suggest, between as little as 8% to 15% of the account balance should be converted to annuities that starts paying income between the ages of 80 and 85.

Having the QLAC would be tantamount to having as much as 20% more savings, they wrote. In their words, “Defaulting a fixed fraction of workers’ 401(k) assets over a dollar threshold is a cost-effective and appealing way to enhance retirement security, enhancing welfare by up to 20% of retiree plan accruals.”

The option would be more productive if people could exercise control over how much to annuitize and when to start payments, the paper said. “When participants can select their own optimal annuitization rates, welfare increases by 5-20% of average retirement plan accruals as of age 66 (assuming average mortality rates), compared to not having access to LIAs.”

Results are less positive for those with higher-than-average mortality rates, the paper notes. Since high mortality and low savings rates tend to go together, the authors suggest that “converting retirement assets into a longevity annuity only for those having at least $65,000 in their retirement accounts overcomes this problem.”

How many TIAA participants buy annuities?

A still-in-progress paper, “New Evidence on the Choice of Retirement Income Strategies: Annuities vs. Other Options,” describes individual annuity purchasing decision patterns among TIAA’s 403(b) plan participants since 1999. TIAA’s plan includes a multi-premium annuity option whose value builds up over time and which offers an opportunity for rising income in retirement.

Authors Jeffrey Brown, University of Illinois, James Poterba, MIT and the National Bureau of Economic Research, and David Richardson, TIAA, found that TIAA participants, most of whom work at colleges and universities, vary widely in their tendency to buy annuities.

Poterba said the data point to three conclusions so far:

- There’s been a gradual shift away from annuities and toward minimum distribution payout options among TIAA beneficiaries over the past two decades. Almost 60% (59%) of initial income selections by TIAA participants in 1999 were either single or joint life annuities, compared with 30% in 2016. Minimum distribution options were selected by 20% in 1999, compared with 59% in 2016.

- Among those who chose an annuity, not everyone chose the same type of contract. Among men who selected an annuity as a payout option in 2016, 37% chose single-life (11% without a guarantee, the other 26% with some guarantee period), and 63% chose a joint life (44% with full benefits to survivor and a guarantee period).

- For unknown reasons, a small but significant group of participants—about 12% in our sample—showed an “annuitization lag.” These participants waited at least three years between the year when they last contributed to their plan and the year when they first drew annuity benefits.

“Only a minority of participants follow the strategy of accumulating until they retire, and then either purchasing an annuity or rolling their plan balance to an IRA,” the abstract of the paper said. “Many participants defer distributions until many years after their last contribution. Among those who annuitize, annuitizing part of the plan accumulation is more common than annuitizing the entire accumulation.”

To be wealthy, choose your parents well

Having smart, successful, healthy parents matters a lot in determining what kind of retirement you’ll have, says the paper, “Longitudinal Determinants of End-of-Life Wealth Inequality,” by James Poterba, Steven Venti of Dartmouth and David A. Wise of Harvard.

The determinants of your wealth tend to differ, depending on your age. In early life, it helps to have wealthy parents or grandparents. Wealth “dispersion in the first few decades of adult life,” the authors write, “reflects variation in the receipt of inter vivos transfers” [from living parents or grandparents, say].

In early adulthood, those who have good jobs have more money than those who don’t. In mid-life, those who’ve used their savings to make good investments naturally have more money. By retirement age, wealth is further determined by intergenerational wealth transfers—inheritances—and health. Those who feel healthy enough to keep working and saving have a clear advantage.

“Later in life,” the authors continue, “the rate of return on investments, the ability to continue working, receipt of a bequest, and the presence or absence of medical expenses contribute to the dispersion of wealth.”

Looking only at Americans who died by age 80, the authors found most Americans who enter retirement with a substantial amount of savings haven’t run out of money by the time they died. Those who do usually had very little wealth at retirement, lost a spouse and/or lacked adequate health insurance in retirement.

“About one third of the households… report lower wealth at death than at retirement,” the paper said. “The onset of a major health condition is associated with an increase in the fraction of persons with wealth below $100,000 from 21.3% to 23.8%. The loss of a spouse is associated with an increase in the likelihood of low wealth from 29.5% to 31.6% percent for [widowers] and from 27.2% to 30.5% for [widows].”

Why so many Chileans bought annuities at retirement

Cheaper annuity prices and the absence of crowding-out by a U.S.-style Social Security system in Chile help explain why more than 70% of single participants in Chile’s privatized defined contribution retirement system buy private life annuities with their savings at retirement.

So say Manisha Padi of the University of Chicago Law School and Gaston Llanes of Northwestern University, the authors of “Competition, Asymmetric Information, and the Annuity Puzzle: Evidence from a Government-run Exchange in Chile.”

Since 1980, when the private system was set up, Chilean workers have been saving 10% of pay each year in funds managed by state-approved Administrators of Pensions Funds, or AFPs, and buying annuities from insurers, including MetLife and Ohio National.

At retirement, participants can either buy a life annuity or take “programmed withdrawals” (PW). The PW option offers high payouts in early retirement than the annuity, a death benefit for bequest purposes, but no assurance of adequate income late in life.

Chileans with high DC balances can get excellent pricing on annuities under this system. Chileans buy annuities with all or part of their DC savings by soliciting bids from insurers through a government-run exchange “that lowers search costs and allows highly personalized pricing.”

For low-wealth annuitants, fewer insurers place bids and the markups can equal 10% to 15% from fair actuarial value, as in the U.S. For high-wealth annuitants, insurers bid harder and markups are much lower. The average markup is 4% over actuarially fair. [This system was unpopular and is undergoing change. See below.]

Just as important, Chileans have no source of insurance against running out of money in retirement other than the private annuity market. There is less adverse selection in the Chilean market because there is no equivalent to U.S.-style Social Security in Chile.

“If Americans no longer had the option to take Social Security, and instead had to take a phased withdrawal of the equivalent amount of money,” Padi told RIJ in an interview,” they would be more likely to purchase an income annuity with their private savings.”

One remaining question that’s not answered in the paper: Would as many Chileans still annuitize if, instead of PW, they could take all of their DC savings as a lump sum, as the vast majority of Americans do.

But Chile’s individualized DC-only system has not been universally popular, and reforms have been proposed so that employers and the government bear more of the pension risk. In September 2017, after the Padi-Illanes paper was written, Chile’s government proposed that employers contribute an additional 5% of income towards a mixed public-private system.

The system called New Collective Savings, would take 2% of the new employer contribution while the remaining 3% would be added to the individual’s private account. The “Collective Savings Council,” a non-profit entity, will manage the assets. The future of this reform remains unknown, given the pending takeover of a new government in March.

In Chile, participants who took more risk got higher rewards

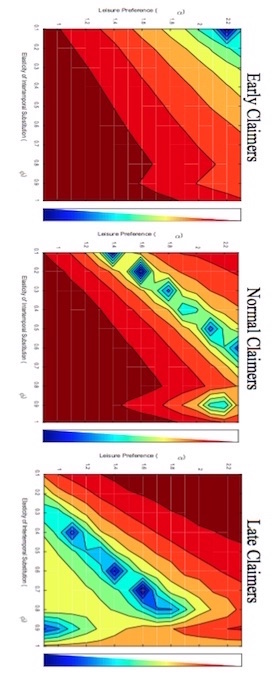

By taking a little more risk and making slightly higher contributions, participants in defined contribution plans can significantly increase their balances at retirement, according to “Financial Investments Through the Life Cycle and Individual Risk Aversion: An Application To Private Retirement Systems,” by Marcela Parada of the Universidad Católica de Chile.

The research was based on the first four waves (2002-2009) of the Chilean Survey of Social Protection (EPS), a dataset that contains observed measures of risk aversion for a representative sample of the population over time and captures Chile’s long history with contributory retirement systems.

“Over seven years, slightly riskier investment strategies may increase individual asset accumulation by 8% or more,” she writes. “I find that individuals tend to quickly react to riskier investment strategies, despite the observed inertia in their behavior. This shows that their risk tolerance affects their optimal behavior and optimally influences their inertia in investments.”

Parada also found that increasing the mandatory defined contribution rate by three percentage points would generate 10% higher accumulations and an increase of five percentage points would generate 16% higher accumulations, “without generating crowding-out effects for financial investments.”

She also saw significant retirement benefits from part-time jobs for women who are also occupied raising children. “Employment opportunities for women with children who are currently not employed to hold a part-time job, generate a mean significant increase by 10% percent in asset accumulation, over 7 years,” she observed, adding that “other characteristics such as health status and family characteristics also have a significant effect on wealth accumulation.”

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.