Retirement Income Journal takes a holiday break

A Merry Christmas and Happy New Year to all of our readers and advertisers. Retirement Income Journal will take its annual holiday break after today, returning with the January 6, 2022 issue. Next year will be our 14th year of publication, with 624 weekly issues published so far. Thank you for making subscription journalism and enterprise reporting possible.

Great American offers fixed multi-year guaranteed rate annuity for RIAs

Great American Life Insurance Co., a subsidiary of MassMutual, has launched the Advantage 5 Advisory, its first fee-based fixed annuity. In a release, the company said the move “deepens its commitment to the registered investment advisor (RIA) channel.”

The Advantage 5 Advisory offers an annual interest rate yield (3.00% for premiums of $250k or more and 2.75% for premiums of less than $250k, as of December 6, 2021) that is guaranteed for the product’s initial five-year term. It is designed for investment advisors whose clients want complete protection from market risk and an alternative to volatile or low-yielding cash allocations, the release said.

“Since launching the industry’s first fee-based fixed-indexed annuity in 2016, we’ve prided ourselves on being a leader in the RIA space,” said Tony Compton, Great American Life’s Divisional Vice President of Broker/Dealer & RIA sales.

The Advantage 5 Advisory is designed to integrate within advisors’ existing toolkits. It can be displayed on many popular fee-based platforms used for portfolio management, reporting and billing.

The Advantage 5 Advisory is Great American Life’s fourth product developed for the RIA space and is available alongside the Index Protector series of fixed-indexed annuities.

Lincoln’s 401(k) adds Income America 5For Life

Lincoln Financial Group will offer Income America 5ForLife, an in-plan target date fund series to participants (generally all employees of Lincoln) in the Lincoln National Corporation 401(k) Savings Plan. This option enables plan participants to turn their savings into monthly retirement income for life.

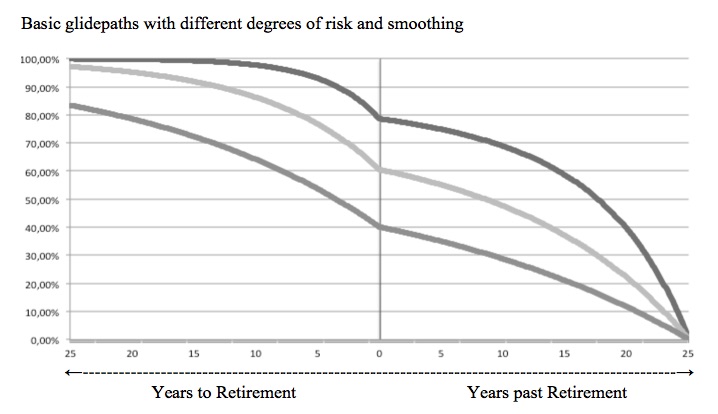

Income America 5ForLife is built on a target date glide path designed by American Century and held in a portable, non-proprietary, multi-insured and multi-managed Collective Investment Trust (CIT). It is designed to be SECURE Act-compliant and to meet ERISA 404 and 3(38) fiduciary requirements.

Income America is a series of target date funds with a novel type of guaranteed lifetime withdrawal benefit (GLWB) rider attached. The rider, called “5ForLife,” promises to pay plan participants 5% of their benefit base (the greater of the account value or net contributions at age 65) every year for the rest of their life. It doesn’t guarantee accumulation. The all-in expense ratio: 1.3% per year.

Income America is a cooperative venture by Prime Capital Investment Advisors; Lincoln Financial and Nationwide (as co-guarantors of the 5ForLife group annuity); American Century (as TDF glide-path designer); Vanguard, Fidelity and Prudential (as fund providers); Wilmington Trust and Wilshire (as fiduciaries); and SS&C, whose “middleware” would wire it all together and ensure portability when participants change jobs.

Jackson buys back 2.2 million shares of common stock; promotes Romine and Reed

Jackson Financial Inc., as part of its previously disclosed $300 million share repurchase program, has signed agreements to repurchase Class A common stock from Prudential plc (which is not related to Prudential, the US company) and Athene Co-Invest Reinsurance Affiliate 1A Ltd. for about US $125 million.

Jackson is repurchasing a total of 2,242,516 shares of its Class A common stock from Prudential, consistent with Prudential’s previously disclosed intent to sell a portion of its ownership of Jackson shares. Jackson is also repurchasing a total of 1,134,767 shares of its Class A common stock from Athene. The transactions are being funded with cash on hand.

The repurchases bring Jackson’s total share repurchases to approximately US $185 million under the share repurchase program. “Additional repurchases under the program may be made through open market purchases, unsolicited or solicited privately negotiated transactions, or in such other manner and at such times as management determines in compliance with applicable legal requirements. The number of shares to be repurchased and the timing of such transactions will depend on a variety of factors, including market conditions. Management reserves its right to amend or terminate the program at any time in its discretion,” a Jackson release said.

Jackson Financial also announced that Scott Romine has been appointed President of Jackson National Life Distributors LLC (JNLD), the marketing and distribution business of Jackson National Life Insurance Company. Scott will also be a member of Jackson’s Executive Committee, reporting to Chief Executive Officer, Laura Prieskorn.

In addition, the company said Alison Reed would be the Chief Operating Officer of JNLD, with responsibility for Distribution Services, Distribution Marketing and Product Solutions. She will report to Romine. Reed has been with Jackson almost twenty years, with leadership roles in annuity product management and National Planning Holdings.

SEC proposes more disclosure of stock buybacks

The Securities and Exchange Commission has proposed amendments to its rules regarding disclosure about an issuer’s repurchases of its equity securities, often referred to as buybacks.

The proposed rules would require an issuer to provide a new Form SR before the end of the first business day following the day the issuer executes a share repurchase. Form SR would require disclosure identifying the class of securities purchased, the total amount purchased, the average price paid, as well as the aggregate total amount purchased on the open market in reliance on the safe harbor in Exchange Act Rule 10b-18 or pursuant to a plan that is intended to satisfy the affirmative defense conditions of Exchange Act Rule 10b5-1(c).

The proposed amendments also would enhance existing periodic disclosure requirements regarding repurchases of an issuer’s equity securities. Specifically, the proposed amendments would require an issuer to disclose: the objective or rationale for the share repurchases and the process or criteria used to determine the repurchase amounts; any policies and procedures relating to purchases and sales of the issuer’s securities by its officers and directors during a repurchase program, including any restriction on such transactions; and whether the issuer is making its repurchases pursuant to a plan that it intends to satisfy the affirmative defense conditions of Exchange Act Rule 10b5-1(c) and/or the conditions of the Exchange Act Rule 10b-18 non-exclusive safe harbor.

The proposed rules apply to issuers that repurchase securities registered under Section 12 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, including foreign private issuers and certain registered closed-end funds.

The proposal will be published on SEC.gov and in the Federal Register. The comment period will remain open for 45 days after publication in the Federal Register.

US life/annuity sector now ‘stable’: AM Best

AM Best has revised its market segment outlook to stable from negative as the segment has experienced a number of improvements, including capital market gains and diversified earnings streams that helped offset the mortality impacts of the pandemic.

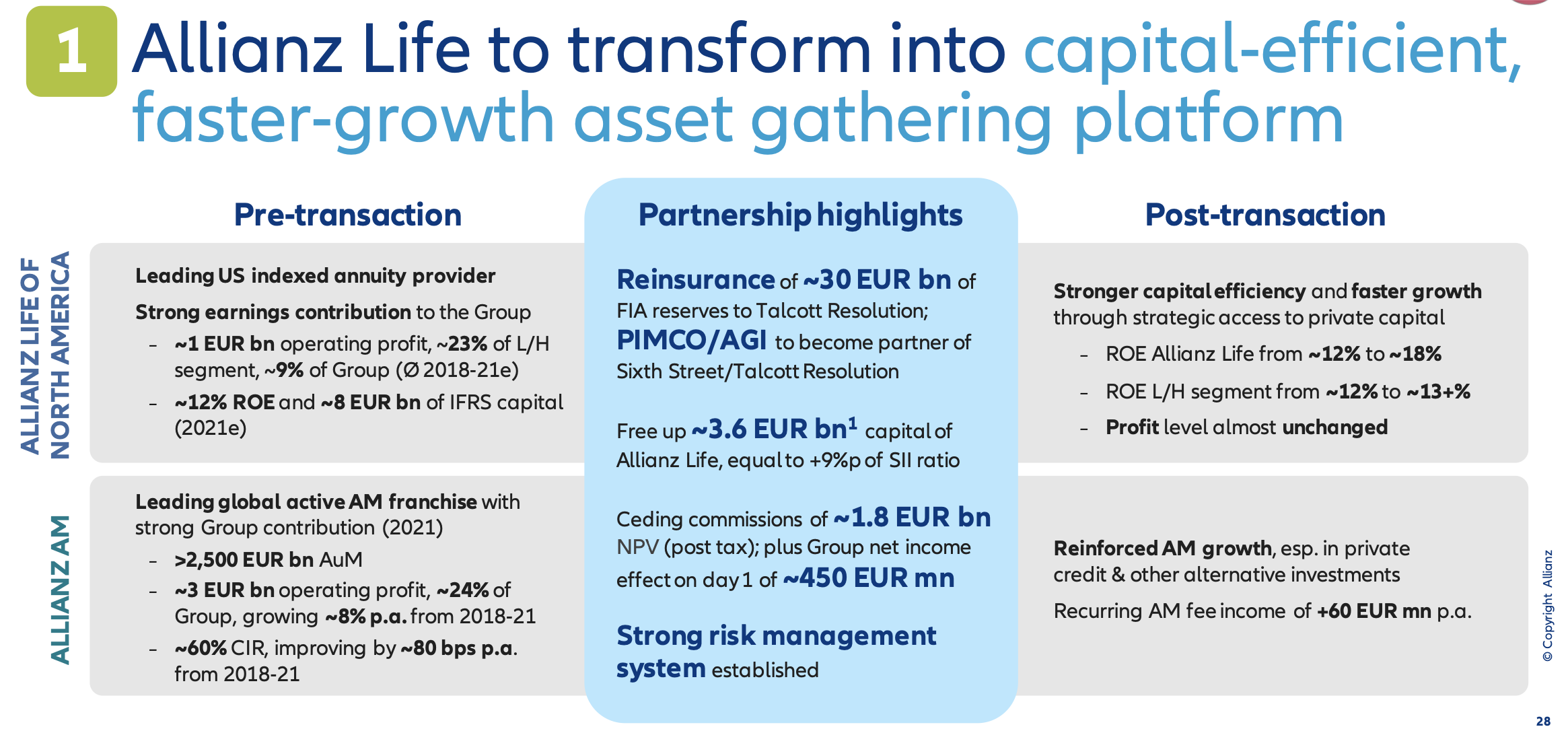

In its new Best’s Market Segment Report, “Market Segment Outlook: U.S. Life/Annuity,” AM Best states that underpinning the outlook revision are record levels of capitalization and improved earnings. Death claims have impacted earnings, but many leading companies have reported strong product sales in the second and third quarters of 2021. Additionally, credit losses in commercial mortgages and fixed-income assets have been muted and well below expectations. Insurers also have benefited from stronger risk management frameworks to shed legacy businesses in a robust transaction market.

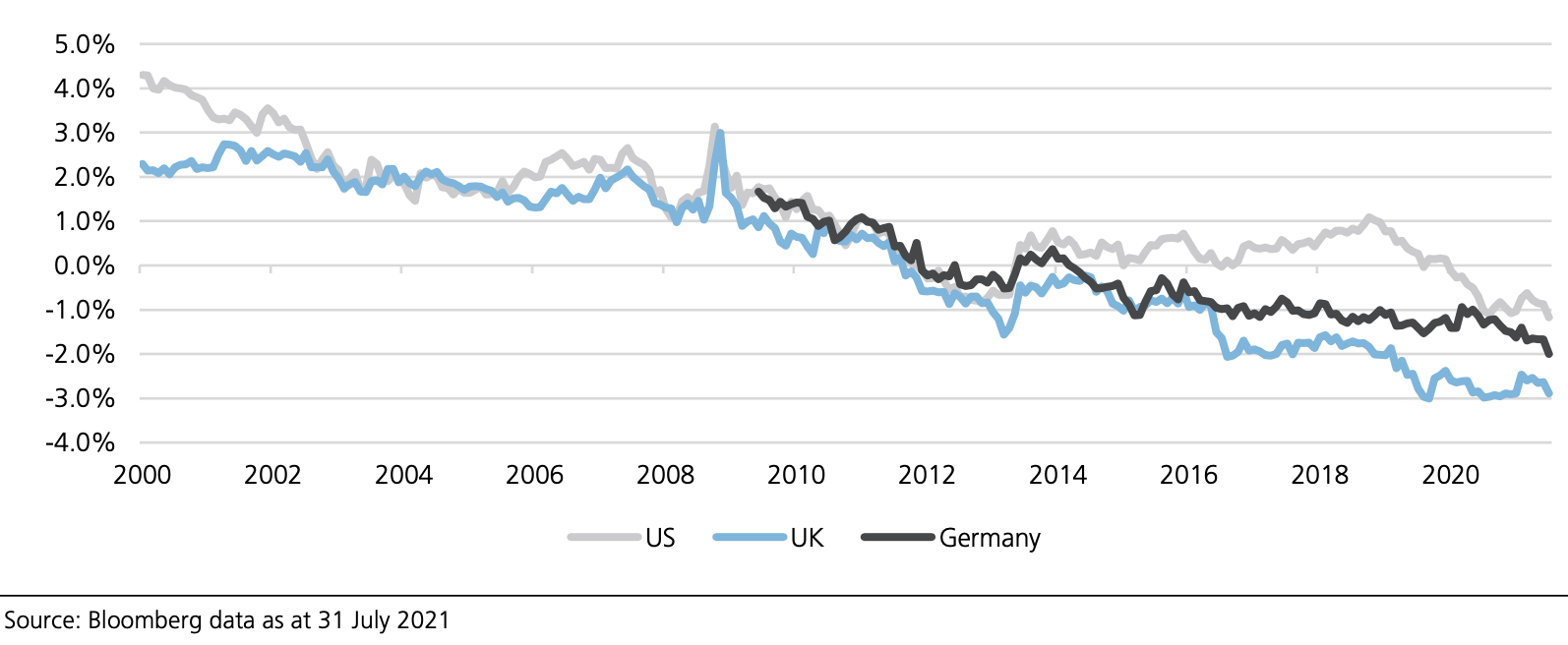

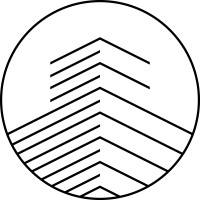

The low interest rate environment remains, but has fueled the acquisitions of legacy block of business, including variable annuities, pension risk transfer blocks and interest rate-sensitive blocks. According to the report, current market dynamics are allowing for liability-side balance sheet restructuring. Insurers are benefitting from lower costs of capital and strong liquidity, which will position them well as the economy improves and if interest rates rise and inflation recedes.

Several pre-COVID-19 pandemic trends have accelerated, including the pivot by life/annuity insurers to fee-based business models that are less sensitive to capital market movements. Although shifts of this kind take time to materialize fully, the formation of new reinsurers, most often backed by private equity, has allowed for a more rapid flow of capital into the industry. This also has intensified the competition for available legacy books of business. AM Best views the additional capital as a positive, while also recognizing a still-developing business model that tilts to riskier but with higher-yield assets.

Although the life/annuity segment faces hurdles heading into 2022, including continuing COVID-19 cases and death claims, as well as inflationary headwinds, AM Best’s view is that carriers will be able to address these challenges because of the improvements in capitalization, profitability and enterprise risk management practices.

To access the full copy of this market segment report, please visit http://www3.ambest.com/bestweek/purchase.asp?record_code=315385.

Athene Holding invests in Hong Kong insurer

Bermuda domiciled Athene Holdings is among the investors that have helped FWD Group raise $1.425 billion, it was announced today, according to reports by Reuters and Bermuda: Re+ ILS.

FWD, the Hong Kong insurer founded by Richard Li and backed by Swiss Re, will use the funds raised to help boost growth and reduce leverage, the reports said.

Retirement services business Athene invested through a subsidiary, and the deal was led by Athene’s asset manager Apollo Global Management with Canada Pension Plan Investment Board. Other investors included Li Ka Shing Foundation, Metro Pacific Investments Corporation, Pacific Century Group, The Siam Commercial Bank Public Company Limited and Swiss Re.

According to Reuters, FWD is expected to launch an initial public offering in Hong Kong after regulatory approval for a $2 billion to $3 billion US IPO was delayed. The size and time frame of the Hong Kong IPO has yet to be determined, according to Reuters’ sources.

Athene and Apollo merged earlier this year in an all-stock transaction after a long-standing partnership.

© 2021 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

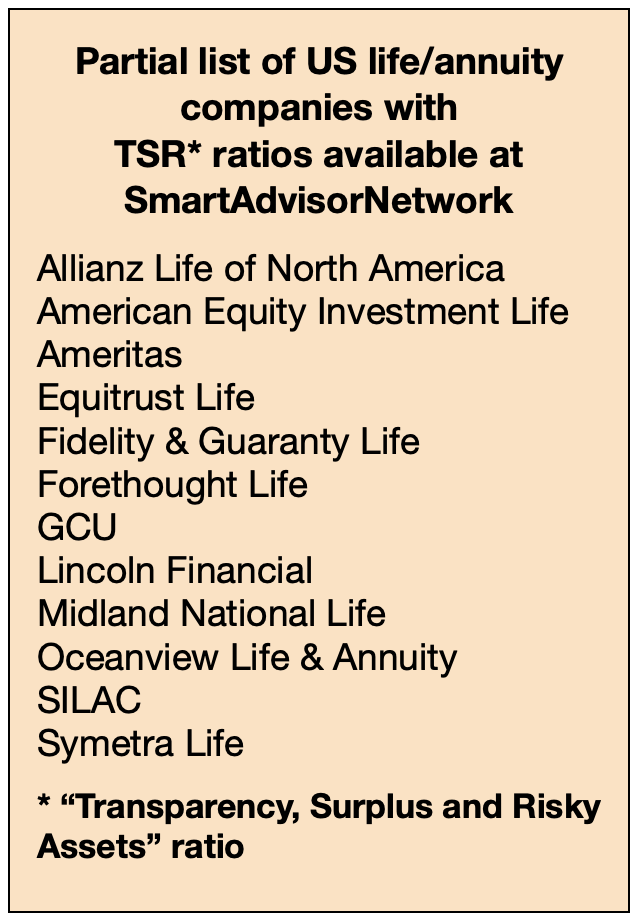

One prominent company affiliated with a giant private-equity holding company has a TSR ratio of more than 6,000. According to the Smart Advisor Network website, this company has a reported surplus of less than $2 billion but combined risky assets (Assets in the NAIC category known as “Schedule D” as well as assets reinsured by related companies or offshore) of more than $80 billion.

One prominent company affiliated with a giant private-equity holding company has a TSR ratio of more than 6,000. According to the Smart Advisor Network website, this company has a reported surplus of less than $2 billion but combined risky assets (Assets in the NAIC category known as “Schedule D” as well as assets reinsured by related companies or offshore) of more than $80 billion.