On the first full day of the Insured Retirement Institute’s annual conference in Boston this week, Prudential’s Bruce Ferris presented a slide on which a bar chart of annual variable annuity sales overlay a line graph of the S&P 500’s yearly performance.

The close correlation between VA sales and the vagaries of the U.S. equities market was evident, and Ferris called it an “unacceptable” pattern for the industry’s future growth.

Later, Ferris commented that another guest speaker, on viewing the same slide, had said, “It should be the opposite.”

That slide seemed to sum up the dilemma that confronts VA manufacturers today. They’re trying to position VAs as a financial product for all seasons—a parasol in the sun and an umbrella in the rain—but it’s tough to have it both ways. Those who live by the bull appear likely to die by the bull.

In a life insurers’ perfect world, VA sales would rise with equity prices and then soar even higher during slumps; but that hasn’t been the case. The upshot is that variable annuities remain, in effect, a segment of the equity mutual fund market rather than a distinct and unique product category.

LIMRA statistics keep showing that most people who buy VAs buy the riders. But if the GLWBs and GWIBs were causing sales instead of just being associated with them, then shouldn’t VAs enjoy strong sales during down markets?

The industry’s strategy for enhancing popularity is (and has been for at least five years): more education and more outreach to advisors and to the public about the special virtues of VAs. IRI, for its part, has been adding distributors to its membership—80,000 individual advisors, Cathy Weatherford said in her presentation—and trying to educate them about annuities, including SPIAs (there’s a new SPIA payout calculator on the IRI site, for members only. It’s powered by information from Cannex.)

But education so far hasn’t accomplished much. Perhaps VA living benefits should simply be presented as what they are: promises that if you’re still alive and if your account has runs out, you’ll keep receiving an income until you’re dead (as long as you accept certain restrictions and conditions). If so, then people might be less mystified by them and they might require less “education.”

Still, VA manufacturers can’t be blamed for the straightjacketed financial environment, one that gives them little ability to generate value for shareholders, customers, distributors or employees.

What advisors and pundits say

During a session where 11 advisors responded to questions from a moderator, the audience of 500 or so was able to hear what advisors think about their products. Advisors don’t mind, for instance, the fact that products undergo frequent changes—they judge each version on its own merits. And they like knowledgeable inside wholesalers who provide support over the phone.

On the other hand, they don’t like the loose price bands that give issuers ample room to raise rider expense ratios in the future. They especially don’t like (a perennial complaint) wholesalers who drill them with product features while not warning them about clawbacks and not showing them what type of client would benefit most from a given contract. Only two of the 11 advisors said they use immediate annuities.

On the second day of the conference, there was another moderated discussion featuring broker-dealers, with panelists from Merrill Lynch, LPL, Raymond James and Morgan Stanley Smith Barney. Give-and-take sessions like that one are now a rarity at IRI conferences, however. Breakout sessions have been eliminated and general sessions with big-picture speakers are the rule.

The headliners at IRI this year included Fareed Zakaria, the CNN commentator, Andrew Friedman, the Washington observer, as well as Gary Bhojwani, president and CEO of Allianz Life of North America, chief marketing strategist David Kelly of J.P. Morgan Funds, and Mohamed El-Erian, the CEO and co-CIO of PIMCO.

Zakaria described the dreary situation that the U.S. finds itself in, a state of affairs where U.S. companies have $2 trillion of cash on their books and are producing the same amount of goods they did five years ago but with seven million fewer American workers. That depresses demand and feeds unemployment in a vicious cycle.

His solution was decidedly Keynesian. The way to break the cycle is for government to invest in research and development and infrastructure, he said. Austerity and cutbacks in federal aid to state and local governments are counterproductive.

“The short-term effect of austerity is falling demand,” he said. “If you downside the government, cut jobs and stop giving money to people, you withdraw money from the economy, you lower tax receipts and you widen the deficit.”

Friedman’s speech, by contrast, was implicitly sympathetic to those who might be footing the bill for that spending through higher tax rates.

If current law prevails, he said, the anticipated 3.8% Medicare surtax on unearned income, combined with a likely return to a 39.6% top marginal income tax rate, would bring the highest effective marginal rate to about 44%. (His math wasn’t entirely clear). In addition, the capital gains tax rate will go to 20% from 15%, the dividends tax rate to 44% from 15% and the estate tax to 55% from 35% with the end of the Bush tax cuts.

Friedman, a Harvard-trained lawyer, predicted that Obama would be re-elected, and that the Republicans would retain the House and gain a majority in the Senate—but not the 60-seat super-majority that would enable them to overcome Democratic filibusters. Gridlock government is likely to last until at least 2016, he said.

Even if Obama were defeated, Friedman said, the Bush tax cuts would still expire on his watch in January 1, 2013, and he can veto any bill to extend the cuts that Republicans try to pass before then. Less sanguine than Zakaria, Friedman expected deficit reduction to trump stimulus. “We’re headed to austerity,” Friedman said. “It’s just a matter of how fast.”

Is it “Boom Time”?

A retirement income Trifecta occurred this week, with three organizations sponsoring meetings. In addition to the IRI conference, the Retirement Income Industry Association held its annual meeting and awards dinner in Boston on October 3 and 4. On October 4, Financial Engines and the Pension Research Council of the University of Pennsylvania staged a one-day, research and public policy-oriented retirement symposium in New York.

The theme of the IRI conference this year was, “It’s Boom Time.” One consultant responded privately, “What boom?” A day after the conference, an executive who used to attend every NAVA conference but has since retired, asked me in an e-mail, “Are they still relevant?”

Occasional complaints are heard about IRI’s steep membership fees and about the lack of substantive breakout sessions at the conferences, but this year’s annual conference was probably the most robust since the end of 2008, especially considering the recent Wall Street sell-offs.

IRI meetings are still probably one of the best places for former insurance company colleagues, now at different companies, to reunite for a few hours. But the days when NAVA members could mix business with golf and spa treatments at La Quinta in Palm Springs are a rapidly fading memory.

© 2011 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

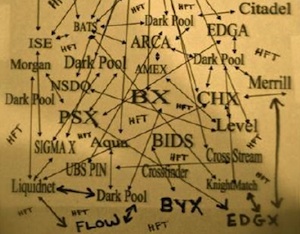

opportunities in what has become a highly fragmented trading world. (The illustration at right is their informal map of the many platforms on which equities are traded throughout the U.S. today.)

opportunities in what has become a highly fragmented trading world. (The illustration at right is their informal map of the many platforms on which equities are traded throughout the U.S. today.)