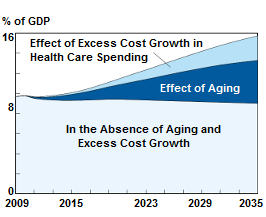

Factors Explaining Future Federal Spending on Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security

Source: Congressional Budget Office, November 2009

IssueM Articles

Factors Explaining Future Federal Spending on Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security

Source: Congressional Budget Office, November 2009

How financially sophisticated are you? To find out, answer these 18 True or False questions. When you’re finished, compare your answers with the Answer Key at the end of this article. Allot yourself five points for each correct answer.

A perfect score would be 90. The average college-educated person over age 55 scored 61.25, or 68%. If you’re wondering whether you can get continuing education credit for taking the test, the answer is, “Not as far as we know.”

This test was designed by Annamaria Lusardi of Dartmouth College, Olivia S. Mitchell of The Wharton School and Vilsa Curto of Harvard University for people over age 55 with varying levels of education. A paper based on their findings, “Financial Literacy and Financial Sophistication in the Older Population: Evidence from the 2008 HRS,” was published by the Michigan Retirement Research Center at the University of Michigan in September 2009.

1. You should put all your money into the safest investment you can find and accept whatever returns it pays.

2. I understand the stock market reasonably well.

3. An employee of a company with publicly traded stock should have a lot of his or her retirement savings in the company’s stock.

4. It is best to avoid owning stocks of foreign companies.

5. Even older retired people should hold some stocks.

6. You should invest most of your money in either mutual funds or a large number of different stocks instead of just a few stocks.

7.To make money in the stock market, you have to buy and sell stocks often.

8. For a family with a working husband and a wife staying home to take care of their young children, life insurance that will replace three years of income is not enough life insurance.

9. If you invest for the long run, the annual fees of mutual funds are unimportant.

10. If the interest rate falls, bond prices will fall.

11. When an investor spreads money between 20 stocks, rather than 2, the risk of losing a lot of money increases.

12. It is hard to find mutual funds that have annual fees of less than one percent of assets.

13. The more you diversify among stocks, the more of your money you can invest in stocks.

14. If you are smart, it is easy to pick individual company stocks that will have better than average returns.

15. Financially, investing in the stock market is no better than buying lottery tickets.

16. Using money in a bank savings account to pay off credit card debt is usually a good idea.

17. If you start out with $1,000 and earn an average return of 10% per year for 30 years, after compounding, the initial $1,000 will have grown to more than $6,000.

18. It’s possible to invest in the stock market in a way that makes it hard for people to take unfair advantage of you.

Answers.

1. F; 2. T; 3. F; 4. F; 5. T; 6. T; 7. F; 8. T; 9. F; 10. F; 11. F; 12. F; 13. T; 14. F; 15. F; 16. T; 17. T; 18. T.

© 2009 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

Soon after Annamaria Lusardi began her research into financial literacy in the United States—or rather, into the average American’s lack of financial literacy—she experienced a professorial epiphany of sorts.

The Dartmouth economist realized that financial literacy is not a trivial topic, as some of her peers once scoffed. On the contrary, she sensed that anyone who can’t grasp concepts like compound interest is bound to fail in a 21st century society.

“A lot of my colleagues told me that I should work on something more serious,” Lusardi told RIJ in a recent interview. “But people who aren’t well-equipped to make financial decisions are the ones who’ll face more risk in the future.”

Then came the financial crisis of 2008, and Lusardi’s view became mainstream. The near-collapse of the world banking system awakened many people, including several members of the incoming Obama administration, to the fact that what Americans don’t know about money can indeed hurt them—and hurt the country.

Now Lusardi and her frequent co-investigator since 2000, Olivia Mitchell, the director of the Pension Research Council at the Wharton School, are in demand. They’ve been called down to Washington to advise the Treasury Department’s Office of Financial Education.

And last October, they and the RAND Corporation received a $3 million Social Security Administration grant to open a Financial Literacy Center at Wharton and Dartmouth, and to design and pilot new programs to raise America’s financial IQ.

A few days ago, shortly after Lusardi, a native of Milan, Italy, returned from a financial literacy conference in Brazil, she answered a few questions from RIJ. Here’s an edited transcript of that interview.

RIJ: Professor Lusardi, how would you describe the financial knowledge of the average American?

LUSARDI: The result of all the work I have done with Olivia Mitchell, in every age group and every survey we have discovered how little most Americans know about economics and finance.

RIJ: What makes Americans so generally deficient in financial literacy?

LUSARDI: Americans are not alone. We have done surveys in other countries and we find a lack of financial literacy everywhere. It’s not that people are getting worse. It’s that the world has changed. In the past, in our parents’ generation, they didn’t face a lot of difficult financial decisions. The biggest decision they probably made regarded their mortgage.

That situation has changed. Even at a young age, people are faced with financial decisions about credit cards. Workers are now in charge of making decisions about their pensions. They are facing complex financial markets. The world has changed and we need to face those changes.

When we talk about financial literacy, the important word is not financial but literacy. In the past it would be impossible to live in a modern society without being able to read and write. Today’s it’s impossible to live in a modern economic society without being able to read and write financially. Everybody’s making decisions and we cannot get away without equipping people to make those decisions.

RIJ: Do you think it may be too later for the Boomers to learn more about finance?

LUSARDI: It’s not too late. People are making important decisions at every age. What worries me is that making the wrong decision late in life can have dire consequences, because you don’t have time to catch up. If you make a wrong decision about when to draw Social Security, or whether to annuitize your wealth, you might not be able to afford a comfortable retirement.

RIJ: But will financial education help? Even well educated people made dumb mistakes with their money during the real estate boom?

LUSARDI: The idea is not that if we educate people they will not make any more mistakes. It’s like driving licenses. We require them but we can’t eliminate accidents. But we must give them the basics. When I think of financial literacy, I think of things like interest compounding. If you understand that, you will know that it’s important to start saving early and not to borrow at high interest rates.

RIJ: Where would financial education do the most good?

LUSARDI: In 1996, the Jump$tart Coalition for Personal Financial Literacy started doing a study of high school students every two years. They found that only a small group of students is financially literate, and that group is disproportionately composed of white males from college-educated parents. This means that if we don’t introduce financial literacy in school then people will have to learn it from their families. That’s fine if you come from a college-educated family. But not everyone can learn at home. So we need to provide education in school.

We also need to pay attention to specific groups. Financial literacy is lacking among women. That is a big group. Women are in charge of making a lot of financial decisions and they increasingly have to fend for themselves. Women are in the workforce, but their earnings are lower than men’s, they take time off to have kids, they rely on less stable wages, and there is a high divorce rate. So accumulation for a pension is difficult.

RIJ: Rather than try to educate everyone, why not just establish good rules-of-thumb, like ‘Everyone should try to postpone Social Security benefits until they reach age 70?’ Or establish new practices like auto-enrollment in retirement plans.

LUSARDI: There have been statements that automatic enrollment in retirement plans is a solution to financial illiteracy. But if you are in debt you shouldn’t be automatically enrolling in a 401(k) plan. You have to decrease your debt first. Or if you buy an expensive mortgage because you don’t have any liquidity for a down payment, I haven’t helped you by automatically enrolling you in a retirement plan.

‘Everyone should take Social Security at age 70’ is too crude a rule for my taste. And it’s not true that everybody should wait until age 70. On the other hand, it’s not obvious to me why we present the information in such a way that the default appears to be to take it at age 62.

We shouldn’t be telling people that they can start at age 62. We should push them to start much later. I cannot overstate how important it is for people, if they are healthy, to try to take Social Security as late as possible.

RIJ: The retirement crisis seems to have made more people aware of financial literacy.

LUSARDI: If it wasn’t for the financial crisis, I don’t think we would be talking about financial literacy. It’s a teachable moment. I have been working on this since 2000, and I receive few invitations to talk about it. Publishing papers was really difficult. There was a lot of skepticism that lack of financial knowledge could be so powerful.

But the crisis has shown in such a strong way that people are making mistakes. A lot of people didn’t understand what they were doing. From an economist’s point of view, financial literacy is a public good. If people make mistakes, and if we have to rescue them when they do, then it’s really important to do prevention.

There has always been skepticism about financial literacy, but I think the financial crisis has proven us right. People can make very bad mistakes, and those mistakes have consequences for them and for society. So academics are now turning to this issue and are trying to find evidence-based research. We are very humble, we don’t claim that we will be successful in solving the problem of financial literacy, but we want to give it a try.

© 2009 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

The global financial crisis and the analyses of its causes and effects have helped expose the embarrassing fact that Americans don’t know nearly as much about economics, finance or investments as they should.

Leaving aside the revelation that bankers, regulators and even Treasury Secretaries blundered, the crisis highlighted a growing body of evidence that most people can’t answer simple questions about compound interest or investment diversification.

For some researchers, that evidence helps explain why so many Americans fall victim to balloon mortgages and high-interest credit. Even more seriously, it implies that many Boomers aren’t financially competent to plan for their own retirement.

“We find strikingly low levels of debt literacy across the U.S. population,” said a December 2008 paper by Anna Lusardi of Dartmouth and Harvard’s Peter Tufano. “It is particularly severe among women, the elderly, minorities, and those who are divorced and separated.”

And financial ignorance isn’t bliss; it’s expensive. Lusardi estimates that about a third of the $11.2 billion spent in 2008 on late fees and other avoidable credit card charges alone was rung up by “the less knowledgeable,” who pay “46% higher fees than do the more knowledgeable.”

Often mocked by economists as too trivial for serious attention, financial literacy is now getting some respect. Indeed, the federal government this fall funded a $3 million Financial Literacy Center at Dartmouth and the Wharton School, with Lusardi as director. Still, financial literacy experts wonder if Boomers will succeed in building up their math skills before they make fatal errors with their savings.

Three questions

Lusardi, author of “Overcoming the Savings Slump: How to Increase the Effectiveness of Financial Education and Saving Programs” (University of Chicago Press, 2009), has spent much of the last eight years working with Olivia Mitchell, director of the Wharton’s Pension Research Council, to design survey questions to measure financial literacy in the U.S.

Here are some of the questions she’s asked, and that most people get wrong:

1. Suppose you owe $1,000 on your credit card and the interest rate you are charged is 20% per year compounded annually. If you didn’t pay anything off, at this interest rate, how many years would it take for the amount you owe to double?

2. You owe $3,000 on your credit card. You pay a minimum payment of $30 each month. At an Annual Percentage Rate of 12% (or 1% per month), how many years would it take to eliminate your credit card debt if you made no additional new charges?

3. You purchase an appliance, which costs $1,000. To pay for this appliance, you are given the following two options: a) Pay 12 monthly installments of $100 each; b) Borrow at a 20% annual interest rate and pay back $1,200 a year from now. Which is the more advantageous offer?

For the first question, fewer than 36% of those surveyed knew that it would take more than two but less than five years. In the second question, about 35% knew that you could never get out of debt that way. Only about seven percent identified “b” as the correct answer to the third question.

Dire consequences

Those best equipped for success in America—young, white, married, college-educated men—tend to be the most financially literate. Others—those over age 50, the 70% without a college degree, women, African Americans, Hispanics, the divorced and separated—tend to be less so. Among high school students, Lusardi found widespread financial illiteracy, except among white males whose parents are college-educated.

Besides paying higher credit card fees, people who lack financial literacy are less likely to use mutual funds with lower fees, more likely to avoid stocks (especially foreign stocks), less likely to refinance their mortgage when advantageous and less likely to plan for retirement.

It’s not so much that Americans are falling behind in financial literacy, says Lusardi; it’s that the world has become more financially demanding of everyone. In particular, millions of Boomers are not equipped to handle the responsibilities that come from having a defined contribution retirement plan instead of a traditional pension—including the responsibility to know how to take distributions in retirement.

“What worries me is that making the wrong decision late in life can have dire consequences, because you don’t have time to catch up,” Lusardi told RIJ. “If you make a wrong decision about when to draw Social Security, or whether to annuitize your wealth, you might not be able to afford a comfortable retirement.”

The fallout from subprime mortgage crisis showed that all of us suffer when the financially illiterate make mistakes. Taxpayers often have to bail out or rescue people—CEOs and commoners alike—who get themselves into personal or system-threatening financial jams.

What to do about it

Historically, financial literacy has had a low priority among economists. Economic theory rested on the assumption that participants in the marketplace acted rationally and in their own best interest. Even if disadvantaged people lacked financial literacy, some experts felt, that was probably among the least of their problems.

But Lusardi, Mitchell, and a few others give financial literacy much higher priority in the hierarchy of human needs. If you teach people the rudiments of investing, they say, you can equip them to solve their bigger problems—or at least prevent them from sliding into debt, bankruptcy and dependency.

This belief relies on two assumptions, however. First, it assumes that the financially challenged are willing and able to learn. Second, it assumes that people make foolish choices with their money out of ignorance and not because circumstances force them to.

One of the more paternalistic responses to financial illiteracy in the retirement savings arena has been to auto-enroll employees in employer-sponsored plans, to provide default investments such as target-date funds and to automatically hike employees’ contribution rates.

For financial literacy champions, however, these are band-aid solutions that boost assets-under-management without addressing the real problem. For instance, these measures doesn’t show people how to balance their need to save for retirement with their need to save for a down payment on a home or educate their children.

“My view is that many ‘nudge-type’ structures can and probably should be implemented, but they will not be sufficient,” Wharton’s Olivia Mitchell told RIJ in an e-mail. “They don’t teach people to become financial adults, to learn to make their own decisions when the easy answers don’t suffice.

“For instance, we can prohibit frequent trading to combat overconfidence but people will find a way around such restrictions. Or we could rule out certain types of financial transactions—for example, adjustable rate mortgages—but this doesn’t give people the tools to decipher and decide on some as-yet-undiscovered financial instrument.

“We can also enhance disclosure—of credit card interest, etc.—but this won’t stop kids from running up credit when they get card applications in the mail,” she added. “And when things get suddenly complex—when the market tanks and there is 10% joblessness—people need to have thought about how to protect against these eventualities while they still have time to plan ahead.”

© 2009 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

Gary F. Baker, vice president in the retirement income business division of Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Co., has left the company, marking the last of a string of departures from the retirement income group, Investment News reported.

In June, Stephen L. Deschenes, the former senior vice president and chief marketing officer for the group, left MassMutual to join Sun Life Financial Inc.’s U.S. division as senior vice president and general manager of the company’s annuity unit. In August, Tom Johnson, a former senior vice president for retirement income and strategic business development at MassMutual, left the company as part of a restructuring that laid off 500 employees. Johnson has since joined New York Life.

MassMutual launched its retirement income group in 2005, when the firm acquired Jerome S. Golden’s business, called Golden Retirement Resources. The insurer brought on Mr. Baker, an 18-year veteran of GE Capital Assurance Co. (now Genworth Financial Inc.), along with Mr. Deschenes and Mr. Johnson, to run the group.

Over the past couple of years, though, MassMutual has been hit by the market meltdown and ratings downgrades. In response, the company has shifted course to focus on traditional insurance products, according to people familiar with the situation. As a result, the insurer has virtually all but shut down its retirement income group.

© 2009 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

The number of companies offering traditional holiday bonuses in 2009 are at record lows, according to a new survey from Hewitt Associates. While the current economy has accelerated the decrease, Hewitt’s research shows a steady trend away from these bonuses toward the adoption of more formal pay-for-performance programs.

Less than a quarter (24%) of 300 companies surveyed are offering holiday bonuses this year, down from 42% in 2008. Of those giving bonuses, nearly half (49%) will give cash, spending a median of $250 per employee, and 39% will give gift cards with a median value of $35 per employee. One in five companies will give a turkey, ham or other food.

Replacing holiday bonuses are variable pay programs, which have increasingly emerged as the primary pay for performance vehicle for employers and make up a greater portion of an employee’s overall compensation package.

According to Hewitt research, average employer spending on variable pay as a percent of payroll has steadily increased over the past decade, from 9.7 percent in 2000 to 11.2 percent in 2010. Meanwhile, average pay raises have been steadily decreasing. In 2000, average salary increases were 4.3 percent compared to just 1.8 percent, in 2009.

“Holiday bonuses have been falling out of favor in recent years as companies face increased pressure to reduce costs and are more focused on growth and performance,” said Ken Abosch, head of Hewitt’s North American Broad-Based Compensation Consulting practice.

“Instead of giving arbitrary, across-the-board bonuses, employers want to find ways to appropriately reward their highest performing employees. And they are doing this by reserving more of their compensation budgets for bonuses that are based on performance and must be re-earned each year.”

Apparently no one has told CEOs how much even a small company-wide holiday bonus can improve morale and cohesiveness, or how demoralizing and divisive it is for managers to reserve the bulk of the raises for a few often subjectively-chosen “star” performers.

© 2009 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

The board of directors of Goldman Sachs Group, Inc., last Thursday approved changes to its compensation practices for 2009. According to a release on the company’s website:

In a statement, chairman and CEO Lloyd C. Blankfein said, “The measures that we are announcing today reflect the compensation principles that we articulated at our shareholders’ meeting in May. We believe our compensation policies are the strongest in our industry and ensure that compensation accurately reflects the firm’s performance and incentivizes behavior that is in the public’s and our shareholders’ best interests.

“In addition, by subjecting our compensation principles and executive compensation to a shareholder advisory vote, we are further strengthening our dialogue with shareholders on the important issue of compensation.”

© 2009 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

JPMorgan Asset Management lowered its expected long-term (10-15 years) returns for equities and fixed income while boosting the real estate outlook, Stu Schweitzer, global markets strategist, said in a client conference call last week, according to Pensions and Investments Online.

Expected returns for both domestic and international large-cap stocks were lowered by 1.5 percentage points, to 7.5% a year for the S&P 500 and to 7.75% for MSCI EAFE. Emerging markets equity was trimmed only 75 basis points to 9.5%.

In bonds, the expected returns for the Barclays Capital U.S. Aggregate fixed-income benchmark was reduced one percentage point to 4.5%, while the expected return for U.S. high-yield bonds—which have experienced a 50% return this year—was reduced 3.5 percentage points to 7.5%.

In contrast, real estate—currently near 1993 valuations—is expected to produce equity-like returns. REITs are expected to return 7.75%; U.S. direct real estate, 8%; and U.S. value-added real estate, 9.25%.

Meanwhile, the median expected return for private equity is 8.5%. Directional hedge funds are expected to return 7%; non-directional, 5.5%; and fund of funds, 6.5%. Hedge funds are attractive if investors can get into top-quartile funds with low volatility, Mr. Schweitzer said.

Mr. Schweitzer warned that global monetary policy—except for the European Central Bank—will focus more on economic growth than on controlling inflation. He added that yields curves likely will steepen more than expected, reducing bond returns.

© 2009 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

The four remaining wirehouses-Merrill Lynch/Bank of America, Morgan Stanley Smith Barney, Wells Fargo/Wachovia and UBS-control nearly half of all advisor-managed assets, Cerulli Associates reported.

About 80% of their assets, or $3 trillion, is managed by advisor teams that manage over $200 million each and typically have four advisors, one of whom is an asset management specialist, and two administrative staff.

The size of the teams allows them to offer a broader set of services to investors, and their network of external specialists make them suitable for investors with over $1 million in net worth.

These top advisors are unlikely to go independent, Cerulli believes. They tend to be more loyal to the channel due to their ties to their employers’ proprietary offerings and aren’t likely to trade their salaries and bonuses to set up their own shop.

Cerulli predicts the wirehouses will remain an important channel for asset managers, despite the industry trend toward independence. Large wirehouse teams are extremely productive and can be a profitable channel for an asset manager that understands this subset.

In other findings from the December issue of The Cerulli Edge-U.S. Asset Management Edition:

Post crisis, asset managers should provide product options that creatively manage beta, as opposed to only pursuing alpha. This will require a significant change in mindset, however.

In addition to probable 12b-1 regulation changes, trends in the distribution landscape and downward pressure on fees will affect mutual fund industry profitability. Trends include the institutionalization of the sales process, the spread of ETFs and industry consolidation.

© 2009 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

The House of Representatives, by a vote of 223 to 202, approved a Democratic plan last Friday to tighten federal regulation of Wall Street and banks, the New York Times reported. No Republican legislators voted for the bill.

The bill, which is still subject to changes by the White House and the Senate, would:

© 2009 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

Last week, the Congressional Budget Office weighed in on the biggest economic imponderable in the health care debate: how private health insurance premiums will behave under health reform.

Building on its December 2008 CBO health insurance market analysis, CBO forecast largely benign effects from health reform’s private market reforms and subsidies on the vast majority of the presently insured (e.g. voting public).

According to CBO, only 17% of Americans in the so-called non-group market—largely individuals—would see premium increases in 2016 (the CBO reference year), because they would be required to purchase fatter benefits with less economic risk.

CBO believes that the other 83% of the presently insured will see little or no change.

I think the fiscal risks of a partially federalized private health benefit are significantly greater than CBO has suggested.

Estimated premium subsidies in proposed legislation—$574 billion over ten years in HR 3962—are pegged to estimated private health insurance premiums.

If, as a result of legislative intervention, premiums actually rise by, say, double the forecasted rates, Congress will be under fierce political pressure to match the increases, or throw millions of people who depend on subsidies back into the ranks of the uninsured.

Where that additional money would come from in 2016, with trillion-dollar deficits, Social Security transitioning to negative cash flow, and baby boomers flooding onto Medicare, becomes a large question.

What we’re really talking about is trying to predict the fluid dynamics of a $900 billion lake of money—the private insurance premium pool. Lake volume is determined by how private insurers price their products, which, in turn, is determined by how their actuaries forecast both variables that will be politically controlled and variables that are beyond political control.

Terra incognita

Under health reform, the federal government will aggressively restructure insurance underwriting practices. Insurers will be required to:

There is no actuarial roadmap through this completely restructured insurance marketplace. It’s terra incognita, properly labeled “Here There Be Dragons!”

Health reform will also create a new Boulder Dam to hold back the lake—a system of health insurance exchanges that become the gateway to the private market, not only for those presently uninsured, but also for a large number of the currently insured population. The exchange’s rules will be the de facto regulatory hurdle health plans will have to surmount to reach the rest of us.

Some humility is appropriate here for all forecasters: the behavior of that lake of money is a classic complex phenomenon.

Benign assumptions

For all the comforting semblance of objectivity, the CBO’s analysis is just a guess—an educated guess—about how the lake will behave if you completely restructure its boundaries. You can model the heck out of it, but all you really do is reframe your uncertainties.

CBO makes some truly debatable assumptions that lead to their benign forecast:

It is actually hard to construct a rosier scenario than the one CBO created.

What’s really happening

Let’s contrast CBO’s rosy scenario with what’s happening right now in the market segments with the greatest risk-individual and small-group coverage.

Presently, the private insurance cost trend is between 8% and 9% across the health system, and rising. Large groups are seeing rate quotes for 2010 below that number. Individual and small-group clients are seeing mid-to high teen rate increases for 2010.

What accounts for the widening spread between inflation and health costs, and between cost and rate quotes, in the non-group market segment that health reform will restructure?

Actual health care demand—hospital admissions, physician visits, prescriptions filled—remains pretty soggy (flat or low single digits), so whatever is pushing up rates isn’t driven by primary demand.

Why rates run ahead of costs or inflation

Cost shifting is certainly a rising contributor to both spreads—cost above inflation and rates above cost.

CBO seems to think that just because providers charge insurers higher rates than Medicare and Medicaid doesn’t mean that they are shifting costs. If it weren’t for cost shifting, most providers who have margins wouldn’t have them. Private insurance is where all their profits come from.

When Medicare flattened costs under the Balanced Budget Act (BBA) in 1997, the result was a lagged surge in private insurer costs, which peaked in 2003. Coincidence? I don’t think so.

I and my consulting colleagues have spent this fall telling providers that it’s time to learn to make money at Medicare rates, because health reform could eventually force insurers to restructure their contracts or cap their rates.

Another contributor to the spread between the 8-9% cost trend and mid- to high-teen rate increases is the effort by insurers to float their overhead (which is being whittled away at, rather than energetically cut) on a smaller base of profitable risk business.

These plans may have lost as many as nine million risk lives in the past two awful years, and if it were not for hefty Medicare Advantage enrollment gains, a lot of the bigger plans would be in a heap of trouble.

Since Medicare Advantage margins will be sharply cut by health reform, we may be seeing some anticipatory rate increases to small-group and individual subscribers.

Lake Mead of money

All in all, the fiscal risks from an open-ended new entitlement to premium subsidies are likely to be significantly larger than CBO estimates.

Instead of neat economic models with ten variables, we need something closer to chaos theory to explain how the nearly trillion-dollar Lake Mead of money will behave when we completely re-engineer its flow pattern. Perhaps the Corps of Engineers can lend CBO some staff.

Jeff Goldsmith is president of Health Futures, Inc., and author of The Long Baby Boom: An Optimistic Vision for a Graying Generation (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008).

© 2009 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

In the past few years, we have seen the emergence of many new retirement income products. With the exception of guaranteed minimum withdrawal riders on variable annuities, however, we have seen very little in the way of sales of any of the products. In this article, I’ll discuss pros and cons of the various products from my perspective as a financial planner, assess the prospects for these products, and recommend what I believe would be an optimal solution for many people.

The Immediate Annuity

This product has been the “product of the future” for more than a decade, but the future never seems to arrive. Sales limp along at an annual rate of $10 billion or so, compared to $250 billion for deferred annuities. One rationale for the low sales is consumer aversion to large, irreversible financial commitments, particularly where shorter-than-expected longevity would result in a retrospectively bad investment. Sales may also be low because financial salespeople are loath to sell a financial product that kills the prospect of any future rollover commissions. Given the lack of sales push or customer pull, insurance companies don’t devote a lot of resources to developing or promoting such products.

However, despite all the negatives, the immediate annuity is a simple product that can match up well with retirement income needs, particularly if payments increase with inflation. Prospects for this product may improve if 401(k) plans are enhanced to make it easy to convert savings into retirement income. It could become attractive for fee-based planners, but few fee-based planners serve the low- and middle-income clients who could best use the mortality-pooling benefits of an immediate annuity to stretch scarce retirement savings. Also, most financial planners have focused on accumulation and not retirement income products.

The following changes might allow immediate annuities (and other retirement products I’ll discuss later) to play a more prominent role in retirement planning:

Longevity Insurance

This product also goes by the longer name of Advance-Life Delayed Annuity (ALDA). It’s an income annuity where the first payment is delayed for a number of years. For example, a 65-year-old man could purchase longevity insurance that pays an income for life that begins at age 85. If the individual dies before reaching age 85, no payout occurs. The individual would need to plan on making retirement savings last to age 85 and then rely on the longevity insurance for income thereafter. The individual would be freed from the planning challenge of trying to make retirement assets last for an unknown future lifetime.

Because of the income deferral, this product costs less than an immediate annuity. An immediate annuity paying an inflation-adjusted $20,000 per year might cost about $290,000, while longevity insurance paying the same benefit would cost only about $40,000.

This product first came on the market a couple of years ago and I’m aware of two companies that offer it. Anecdotal evidence suggests that sales have been miniscule. As with the immediate annuity, the retirement marketplace doesn’t seem to be set up to pay much attention to this type of product. Also, the financial crisis and the problems faced by a formerly AAA company like AIG have made individuals nervous about buying a product that delays income for 20 or more years.

The product also has a fundamental design problem. Going back to our example, let’s say the individual buys the product and then needs to make other savings last until age 85. If individuals make overly aggressive assumptions about investment growth, they may run out of assets before age 85 and then face a period without income. If they are too conservative, they may reach age 85 with more assets than they need, and may regret not spending more money when they could have enjoyed it.

The fix for this problem would be to combine longevity insurance with a product that guarantees withdrawals until age 85 regardless of investment performance. This would be an acronymic marriage of a limited-term GMWB or RCLA (discussed next) with the ALDA. I believe that longevity insurance has potential as a component in building retirement guarantees, but I don’t foresee strong prospects for it as a stand-alone product.

The Guaranteed Minimum Withdrawal Benefit (GMWB)

This product is offered as a variable annuity rider and has gone through a number of transformations over the decade or so of its existence. The latest version, called the Guaranteed Lifetime Withdrawal Benefit (GLWB), guarantees the annuity purchaser certain minimum withdrawals from the annuity for life (5% of the initial purchase amount is typical), regardless of investment performance. The purchaser pays .50% to 1.00% per year for this rider.

I like this concept for its guarantees, but I have these concerns:

Complexity. This is an “actuaries-gone-wild” product where instead of offering a simple income guarantee based on an initial purchase amount, the product’s guarantees vary with a ratcheting provision based on underlying fund performance. As a financial planner, I would rather show the client something simpler-“Pay X, and y ou’re guaranteed Y-end of story.”

Lack of Inflation Protection. At 2.5% inflation, a 5% fixed guarantee is worth only about 3% in 20 years, and 3% isn’t much of a withdrawal guarantee. I would like to see a product whose guaranteed payouts increase based on actual inflation. Products offered today provide some upside based on underlying fund performance, but the correlation with actual inflation is tenuous.

Cost. A typical variable annuity costs about 2.25% per year. If we add .50% to 1.00% for the rider, we’re near 3.00%. Recent estimates for the premium of future stock returns over bond returns range from 3% to 6%. If that’s the case, a client who uses a variable annuity with a GLWB rider might end up paying out between 50% and 100% of the equity premium in fees.

Rider Utilization. At least one study has shown that, to make best use of the GWLB rider, the customer should take withdrawals at the maximum allowed level immediately after purchase and continue them for life—that is, turn the product into an immediate annuity with an equity-linked refund feature. My impression is that most customers will use the product for accumulation and never call on the income features at all—thereby turning the product into a very expensive mutual fund investment.

In some ways, the GLWB is ideal for guaranteeing retirement income. But its effectiveness in meeting customer needs is seriously compromised. Given the attractive commissions offered on variable annuities, I expect sales to remain strong. But I think there is a better way forward for the customer, and that takes the form of the next product.

Ruin Contingent Life Annuity (RCLA)

This product is the brainchild of Professor Moshe Milevsky of York University in Toronto. He has noted that it is basically an unbundled version of the GLWB. The product was described in detail in Retirement Income Journal so I’ll provide a simplified example here.

Begin with a block of assets that will be used to provide inflation-adjusted withdrawals at some set percentage of the initial amount. The customer purchases a guarantee that if the funds are depleted-due to longevity, poor investment returns, or an adverse sequence of investment returns-the guarantee will kick in and inflation-adjusted payment will continue for life. Because payouts are a function of multiple contingencies-longevity and investment related-the product will cost less than a longevity insurance policy that pays out based on longevity only.

Before illustrating how the RCLA works, I’ll show results for other product solutions. We’ll start with a 65-year-old man with $325,000 of savings and the desire to withdraw an inflation-adjusted $20,000 per year for life. One solution would be simply to invest the money, take systematic withdrawals, and hope the money lasts a lifetime. Assuming 2% inflation, 4% bond returns, 8% stock returns, and a 50/50 stock bond mix, the portfolio would last until age 91. The risks with this approach are: (1) living beyond age 91, (2) experiencing returns lower than assumed, or (3) experiencing a bad sequence of returns, i.e. low returns in the early years of retirement.

A very different solution would be to guarantee a lifetime income by purchasing an immediate annuity. At current rates, an inflation-adjusted annuity generating an initial income of $20,000 might cost about $290,000. That would meet the need for guaranteed lifetime income, but would lock up all but $35,000 of the available funds and leave disappointed heirs if the retiree were to die early.

What about longevity insurance? An ALDA purchased at age 65 and providing $20,000 per year (in today’s dollars) beginning at age 85 would cost about $40,000. That would leave $285,000 to provide income for 20 years. Based on the inflation and investment assumptions used in the systematic withdrawal example above, we would expect the $285,000 to last 22 years-not much margin to guard against bad investment experience. Based on some Monte Carlo analysis, there’s a 44% chance the assets would not last the needed 20 years.

Now let’s look at the RCLA. An RCLA able to produce the required income might cost roughly $20,000, leaving $305,000 as the portfolio on which guaranteed withdrawals would be taken. In effect, we have created the same lifetime guarantee as the immediate annuity, but with $305,000 of initial liquidity for heirs vs. $35,000 if we purchased an immediate annuity. Among legacy-minded retirees, this may lessen the resistance to the initial purchase. (Of course, the $35,000 would be expected to grow over time and the $305,000 to decline, making the immediate annuity potentially the better investment if the retiree lives a long life.) I have not provided an example based on a variable annuity with a GLWB because I am not aware of any that provide a simple inflation guarantee. But with their high expense charges, GLWBs would not produce results as attractive as with the RCLA.

Compared with the RCLA, a disadvantage of annuities and longevity insurance is that the pricing reflects the insurance companies’ cost of holding reserves for such products in fixed income investments. Even though these represent long-term commitments, insurers are not allowed to support them with a mix of stock and bond investments. GLWB and RCLA pricing allows for equity investing and equity option pricing, which means a lower price for consumers.

Conclusion

Both immediate annuities and the RCLA can help clients build secure retirement plans. But neither of them, as I suggested earlier, is likely to get off the drawing board and into retiree portfolios without major changes, such as mandating that retirement savings plans offer the product, subsidizing the growth of the fee-based planner industry, and providing software and training that supports the use of this product. Existing product delivery systems won’t suffice.

© 2009 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

Brent Burns and Steve Huxley of Asset Dedication, LLC, like to compare their retirement income-generating unified managed account methodology to the Apollo moonshot, an event that most Boomers should have no trouble recalling.

The spacecraft’s wobbly moonward path required a lot of course corrections along the way, say the Mill Valley, Calif., entrepreneurs. Similarly, a retirement portfolio won’t adhere to its intended 30-year trajectory without frequent adjustments by an advisor.

That’s one way to describe what they do. But you could also visualize their program as a five-year extension ladder built out of bonds. Each year, if they wish, retired investors and their advisors can keep extending the ladder—presumably until their portfolios are more or less safe from ruin.

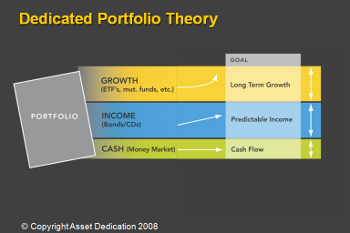

“It’s liability-driven investing for individuals,” said Huxley and Burns in a recent interview with RIJ. “We call it Dedicated Portfolio Theory. It relies on the same institutional concepts that foundations and endowments have used for years.”

“It’s liability-driven investing for individuals,” said Huxley and Burns in a recent interview with RIJ. “We call it Dedicated Portfolio Theory. It relies on the same institutional concepts that foundations and endowments have used for years.”

In recent years, entrepreneurs, insurance companies, and even trade groups have introduced a flock of outcome-based, liability-matching planning methodologies for retirement income generation, offering them as potential alternatives to systematic withdrawals from balanced portfolios. Some employ annuities and some don’t.

Huxley and Burns were pioneers in that movement. With their book, Asset Dedication (McGraw-Hill, 2004), they identified the weaknesses of traditional asset allocation during retirement early on. Even earlier, in 2002, they formed a company with the same name, but didn’t signed up their first client until 2007. Now, having allied with BondDesk Group LLC in November, they’re ramping up their marketing.

Building a “bond bridge”

To a layman’s ears, Asset Dedication’s UMA sounds like a bucket system that’s built around a proprietary bond laddering technique, coupled with an illustration system and integrated with back office support. It includes a one-year cash bucket, a five-year to 10-year bond bucket, and a long-term equity bucket.

The product’s strongest points, its creators say, are that it can deliver predictable inflation-adjusted income year after year and can be customized for each client. Systematic distributions from a bond fund would be a lot more risky, and laddered zero-coupon bonds or a period-certain immediate annuities would be more expensive, they claim.

“Technically, it’s a bond ladder but we call it a bond bridge,” Huxley told RIJ. “It smoothes out income in retirement. Our algorithm reduces the opportunity costs of buying bonds, so you get the most income for the least amount of money. It frees up resources that you can use to extend the bond-bridge or dump into stocks.”

On the other hand, there’s nothing magical about this methodology. While aimed at creating a rolling buffer zone between a retiree’s market-sensitive assets and his or her monthly cash flow, it doesn’t necessarily exempt advisors or clients from potentially difficult timing decisions during retirement, Huxley and Burns conceded.

On the other hand, there’s nothing magical about this methodology. While aimed at creating a rolling buffer zone between a retiree’s market-sensitive assets and his or her monthly cash flow, it doesn’t necessarily exempt advisors or clients from potentially difficult timing decisions during retirement, Huxley and Burns conceded.

“You may have to take a pay cut,” they acknowledged, if it became necessary to buy (“roll over”) an additional year’s income at a time when the portfolio’s equity investments are depressed. The alternative strategy would be to maintain current spending levels and accept an incrementally higher risk of portfolio “ruin.”

The minimum initial investment in the UMA is $250,000 for a household account and $100,000 for management of the bond assets alone. The fee is 35 basis points a year for the first $5 million invested, 25 basis points for the next $5 million and 15 basis points for money over $10 million. Huxley and Burns say the system is designed for low turnover and high tax-efficiency.

Comparisons to funds and annuities

How would Asset Dedication’s five-year bond bridge compare to a five-year period certain immediate annuity? In one of the firm’s published examples, a hypothetical client receives an inflation-adjusted income averaging about $98,000 a year over the first five years of retirement, for an initial cost of $468,000. By comparison, an annuity that produced $98,000 a year for five years, assuming a two percent annual growth rate and no fees, would cost $471,157, according to an annuity calculator at bankrate.com.

Earlier this year, PIMCO introduced a TIPS-based payout fund that provides predictable inflation-adjusted income for 10-year or 20-year intervals. Huxley and Burns were asked to compare it to their product.

“Pimco’s funds are designed as a mutual fund for thousands of clients,” Burns said. “Our strategy generates income specific to each client based on their financial plan. We match the cash flows needed—usually to within one percent—and do this dynamically through the use of rolling horizons. We can use TIPS, Treasuries, AA or better corporate, or munis.

“The best and cheapest solution shifts over time as the spreads between the different fixed income securities change,” he said. “There are times when it is much more expensive to generate the same income profile using TIPS. Right now they are relatively cheap, but two years ago, they were expensive and we have certainly seen them shift that way over the last few weeks.”

But couldn’t an advisor build his or her own bond ladder? “It is not as easy as it sounds,” said Huxley, who teaches at the University of San Francisco School of Business and Management. “Determining the precise number of bonds to buy so as to match cash flows over a period of years can be extremely difficult and time consuming, particularly if cash flows are not steady.”

If investors want to avoid the stress or risk of funding five years of retirement income all at once when they retire, the Asset Dedication system allows them the option of buying a series of five-year bonds, starting five years before retirement.

Target market

Independent fee-based advisors, as opposed to registered reps, are Asset Dedication’s target market. “We dovetail with people who are true financial planners, who are the financial quarterbacks for their clients who provide comprehensive advice, not just investment advice,” Burns said.

“We’re just a piece of what they do. They drive the strategy and we drive the implementation. We can’t build our portfolios unless there’s already an investment plan in place,” he added. Asset Dedication has made several presentations to NAPFA (National Association of Personal Financial Advisors), an organization of fee-only advisors.

Advisors should feel at home with Asset Dedication’s choice of strategic partners. Its affiliation with BondDesk Group, begun last month, gives Huxley and Burns access to a large inventory of bonds. (Also based in Mill Valley, Calif., BondDesk is described by BusinessWeek as an odd-lot fixed-income electronic trading platform for broker dealers in North America.)

The low-fee custodians of the UMAs—Schwab, Fidelity and TD Ameritrade—are obviously familiar to advisors. For the equity bucket of their system, Asset Dedication relies on investments managed by Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA), which sells low-cost funds only to select advisors.

© 2009 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

If you’ve attended a retirement income conference anywhere in the continental United States recently, you’ve probably met Kevin S. Seibert, CFP, CEBS, CRC, managing director of the International Foundation for Retirement Education, or InFRE.

A tall, sandy-haired Midwesterner, the Barrington, Ill.-based Seibert logs many thousands of air miles each year, delivering slide presentations at retirement conferences and teaching workshops on retirement income to groups of financial advisors, often at banks and insurance companies.

You may even have heard Seibert describe his epiphany when he broke with the orthodoxy of conventional financial planning and realized that life annuities, by virtue of their mortality credits, can be an important source of retirement income.

If you’ve seen Seibert lately, you may also have heard him announce that the Certified Retirement Counselor designation, which InFRE confers, is now accredited by the National Commission for Certifying Agencies, after two years of work by Seibert and his colleague, Betty Meredith, CFA, CFP, CRC.

If you’ve seen Seibert lately, you may also have heard him announce that the Certified Retirement Counselor designation, which InFRE confers, is now accredited by the National Commission for Certifying Agencies, after two years of work by Seibert and his colleague, Betty Meredith, CFA, CFP, CRC.

So-called “senior designations,” as you probably know, have become objects of controversy. Two years ago, a number of self-described “senior specialists” used flimsy credentials and free lunches to hustle retired investors. Several states began prosecuting them.

Regulations soon followed. The State of Massachusetts eventually banned the use of senior certificates except for those accredited by either the NCCA or the American National Standards Institute, two organizations that certify certifiers.

Financial advisors clearly benefit from having the right acronyms after their names. In the retirement income sphere, several certifying bodies are vying for advisors’ attention. To help advisors understand their options, RIJ has initiated an occasional series on organizations that offer certificates in the retirement space.

A few weeks ago, we reported on the Retirement Management Analyst designation, which is currently in development by the Boston-based Retirement Income Industry Association. This week we report on InFre’s Certified Retirement Counselor designation.

Non-partisan manual

Depending on how much you’ve already read about or know about retirement income, the topics that InFRE’s manuals cover and the skills that are assessed during the four-hour, 200-question CRC exams may either be familiar or entirely new.

InFRE’s 276-page, spiral-bound study guide, “Strategies for Managing Retirement Income,” written by Meredith and Seibert in partnership with NAVA (now the Insured Retirement Institute), presents a six-step process that covers all the basics—client assessment, management of retirement risks, income generation, etc.—in thorough and even-handed detail. It doesn’t push any particular philosophy, other than perhaps the assumption that retirement income planning is quite different from financial planning in mid-life.

“We took a lot of the information that’s already out there, we researched it thoroughly, and we used it to develop Strategies for Managing Retirement Income,” Seibert told RIJ. “That’s our main course of study, but it’s separate from CRC. It goes into more depth than the study guides for the CRC examination.”

The distinction between the educational materials that InFRE promotes and the CRC study guides or “Test Specifications” is an important one. To be NCCA-accredited, a certifying body must show that it isn’t merely using a designation as an excuse to sell textbooks or other paraphernalia. Nor does the NCCA accredit an organization that simply awards a framable “diploma” to people who have completed a specific course of study.

“A certification program isn’t based on the education, it’s based on knowledge,” said Jim Kendzel, executive director of the Institute for Credentialing Excellence, or ICE, of which the NCCA is the accrediting arm. “It’s always linked to an assessment tool, and it always involves a continuing education requirement.”

(The credentialing process presents a kind of infinite regression. InFRE is accredited by NCCA, which is part of ICE. ICE, in turn, is accredited by the American National Standards Institute, whose board consists of officers of major U.S. corporations, academics, and federal officials. ANSI represents the U.S. at the ISO, or International Organization for Standardization, which governs the ISO 9000 quality standards.)

InFRE met those requirements in September, after a two-year application process—and twelve years after the CRC was created. InFRE first developed the designation in 1997 in partnership with the Center for Financial Responsibility at Texas Tech University in Lubbock and with help from a federal grant. It has been certifying and re-certifying financial professionals since then.

“About 2,000 people are accredited or in the process of being accredited, and we’re hoping to go to 3,000 by end of 2010,” Seibert told RIJ. “About 60% to 70% are in financial services. Our growth slowed down last year, as anticipated, because state compliance departments were saying, ‘We’re not going to let you use your retirement designation until it’s accredited.’”

One of the first to receive the CRC from InFRE was Linda Laborde Deane, CFP, AIF (Accredited Investment Fiduciary) of Deane Retirement Strategies in New Orleans. Her son Keith, a 2008 University of Georgia graduate, is among the most recent to start the CRC process.

“The more credentialing you have, the more clients respect you and the more confidence they have in you,” she told RIJ. “It’s important that CRC has continuing education requirements because clients are aware of that—that is, if you make them aware of it.”

Deane sees no need for annuities for her retired clients, preferring to rely on prudent, adjustable systematic withdrawals for income. She advises her clients each year on how much they can afford to harvest from their accounts. Though not a market timer, she watches the markets closely. In July 2006 she eased back to a 50/50 balance of stocks and bonds, then stood pat. “My clients went through 2008 without any decrease in their income,” she said.

Annuity revelation

Seibert joined InFRE in 2003. A graduate of Miami University of Ohio with an MBA from the University of Wisconsin, he founded and operated Balance Financial Services, a Chicago financial planning and consulting in 1988. Earlier, he’d been a consultant at William M. Mercer Inc., specializing in employee benefits.

His financial life includes a conversion of sorts. “When you grow up in the fee-only CFP world, you’re taught to think that annuities are bad.” He had not considered the mortality pooling effect, however, which enhances the wealth of the surviving annuity owners.

“That was something of a revelation,” he said. “And you’re not just getting more income than you would otherwise. You’re preserving your managed assets as well by making sure that your basic needs will always be met. One of the cons of annuities is that they take away from your estate. But the opposite is true. If you live a long time, they can preserve your estate.”

You might notice that Seibert and Deane don’t hold identical views on the value of income annuities. But then, there’s nothing in the CRC designation that says they have to.

© 2009 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

The QWeMA Group Inc., the Toronto-based financial engineering group led by Moshe Milevsky, plans to launch an index that will enable retirees to buy a type of annuity that they can get today only by purchasing a variable annuity or a separate account with a living benefit rider.

The index, to be introduced January 1, 2010, will allow the development of a new type of ultra-inexpensive deferred income annuity that QWeMA calls a Ruin-Continent Life Annuity (RCLA). It will be the subject of Milevsky’s column in Research magazine next month.

The RCLA would resemble a variable annuity lifetime withdrawal benefit, which pays the insured parties an income for life only if their accounts are exhausted by a combination of systematic withdrawals and poor market performance before they die.

Where a VA living benefit or even a SALB (stand-alone living benefit) is triggered by a decline in the client’s account balance, however, the RCLA payout would be triggered by a decline in QWeMA’s “sustainable portfolio withdrawal index,” which would mimic a decumulating portfolio.

To look at it another way, the RCLA would be like an advanced life deferred annuity (ALDA), only much cheaper. An ALDA pays out if the annuitant reaches some advanced age, such as 80 or 85. An RCLA would be cheaper because it wouldn’t pay out unless the index had also dropped to its trigger point while the insured was still alive.

“We propose an ALDA in which distinct risk valves must be triggered before an annuitant gets paid,” wrote Milevsky and QWeMA colleagues Huaxiong Huang and Thomas S. Salisbury in an article in the Journal of Wealth Management last spring.

“First and obviously the individual (or spouse) must be alive. But second, to make a claim on their insurance policy, they must have the ill fortune to experience under-average market returns during the years surrounding retirement.”

“The impetus for creating stand-alone RCLA products is that they might appeal to the many soon-to-be-retired baby boomers who are 1) not interested in paying for the entire variable annuity package, and 2) would be willing to consider annuitization, but only as a worst case “Plan B” scenario for financing retirement,” wrote Milevsky and the same co-authors in a January 16, 2009 paper entitled, “Complete Market Valuation for the Ruin-Contingent Life Annuity.”

The index could show investors if they were spending their savings at too high or low a rate, Milevsky said. The insured investor could invest any way he liked or spend at any rate he liked—the trigger point would depend on the index rather than on his account value.

In effect, the insurance would protect retirees from the risk of experiencing terrible returns shortly before or after retirement—so-called sequence-of-returns risk—as well as longevity risk, or the risk of living too long. Although the client would not face direct investment restrictions, as he or she would with a GLWB, the index itself would incorporate benchmark withdrawal rates and asset allocations.

“It’s not like buying fire insurance on your house, where the policy is based on whether your house burns down or not,” Milevsky told RIJ. “It’s more like buying a policy based on the temperature in the neighborhood. It’s an annuity that’s linked to an index that everyone can see every day, so that anti-selection is reduced.”

An RCLA would be priced higher for someone who opts for a higher withdrawal rate than those who choose a lower withdrawal rate, and lower for older retirees than for younger ones. The price would also depend on whether the index was linked to the performance of, for instance, the S&P 500 or of a less-risky balanced portfolio.

“There’s a need for an independent index for benchmarking in retirement,” Milevsky said. “People don’t know what to compare themselves to. Say they retired two years ago and their portfolio is down severely. Is it down because they’re withdrawing too much, or because of the markets? The index would tell them. Advisors could also compare themselves to the index.”

© 2009 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

| Wealth/Income Ratios by Age | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2004 | 2007 | 2009 | |

| Total | 5.39 | 5.91 | 6.19 | 4.57 |

| Under 30 | 1.43 | 1.02 | 1.58 | 1.02 |

| 30-39 | 2.18 | 2.45 | 2.39 | 1.50 |

| 40-49 | 4.00 | 4.31 | 4.57 | 3.30 |

| 50-61 | 6.22 | 6.77 | 6.75 | 5.00 |

| 62+ | 10.84 | 11.34 | 11.05 | 8.44 |

| Source: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, November 2009 | ||||

The publicity and vituperation around the book tour of a middling ex-governor of Alaska seems to have nothing to do with Sarah Palin’s politics, which judging from her term in office are unexceptional and only center-right. The heat derives from her style, which is that of an iconoclast outsider, and from the establishment’s fear that iconoclasm may be the wave of the future. Economically, their fears may be justified, whatever Palin’s future career plans.

Historically, iconoclasm was an 8th-century Byzantine movement in opposition to the religious icons central to Orthodox worship. By smashing icons, the iconoclasts hoped to restore the purity of the Church and focus religious belief on the spiritual —they appear to have had similar impulses to those that later inspired Martin Luther to revolt against the decadent Medici papacy. Their opponents, the “iconodules,” did not just love images, they were regarded as enslaved to them.

In the economic arena, there would seem to be a good case for iconoclasm. The bipartisan support for the bailout in late 2008 and the lack of action thereafter has left the institutional structure frozen, even a year after the event. Citigroup, AIG, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are still in existence, and no plans have been made for their closure or breakup. Wall Street, in the form of Goldman Sachs, is making record profits and will pay even more outrageous bonuses than in the boom year of 2007, yet much of its activity is pure rent-seeking, with no beneficial effect on the outside economy. The U.S. mortgage market is even more hopelessly compromised than it was a year ago, with the combination of the home-buyer tax credit and the Federal Housing Administration’s lax requirements for only a 3% down-payment producing a new $1 trillion pile of mortgages that appear to be toxic.

Other damaging policies that were improvised during the crisis are also still in place, and show no signs of being reversed. Interest rates are still close to zero; indeed bank “window dressing” was reported to have driven interest rates on short-term Treasury bills to below zero. The monetary base was doubled in late 2008, a sharper increase than ever before in the history of the Federal Reserve, yet there is no sign of its decline, while the banking system’s excess reserves pile up at over $1.2 trillion. On the fiscal side, the 2009 budget deficit was $1.4 trillion and the 2010 deficit promises to be still larger. President Obama has vowed to reduce the deficit, but it has become clear that for this administration the mantra should be “Watch what we do not what we say.” In practice, he remains fully committed to a health-care ‘reform’ proposal that increases both the costs and the budget deficit, by around $1 trillion over the 2011-2020 period.

As I have discussed previously, continued worship of these icons, whether in the form of the bankrupt financial institutions, the zero-interest-rate policies, or the trillion-dollar deficits, will drive the U.S. economy into a renewed downturn that will achieve new records both in terms of pain and difficulty of exit. Yet the iconodules Bernanke, Geithner and Obama continue their worship, and the congressional opposition to them seems content only to vary the forms of ceremony, without producing serious proposals that would break the major icons or even chip them.

Like the 8th-century Byzantine church, the nexus of Washington and Wall Street has grown corrupt and its corruption has come to exert increasing costs on society as a whole. Wall Street has become excessively concentrated, trading dominated and rent-seeking, while its rewards, like those of the overblown Byzantine hierarchy, have become completely out of proportion to the increasingly impoverished lives led by the rest of the population. Goldman Sachs chairman Lloyd Blankfein claims that his organization is “doing God’s work;” St. John of Damascus, the leading iconodule would doubtless have claimed the same on behalf of the Byzantine Church. In Washington, eight years in which the ideology that had been sold to the voters in 2000 was replaced with something quite different, there’s a new clerisy even more enthusiastic to expand the power of government without very much regard as to whether that expansion is either cost effective or helpful to the population as a whole.

In such an atmosphere, with unemployment above 10% and rising, and U.S. living standards descending inexorably towards those of the Third World, it is not surprising that the public beyond the Washington Beltway is in an iconoclastic mood. Its iconoclasm is rational, economically speaking. The tight oligopoly of Wall Street is profiting excessively from its 2008 bailout by taxpayers, with the payments to Goldman Sachs and others on the AIG credit default swaps coming to seem increasingly misguided and possibly corrupt, given Goldman Sachs’s close connection with the Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson who disbursed taxpayers’ money in such an unproductive manner. AIG and Citigroup remain in business, with even AIG Financial Products, the cause of much of 2008’s pain, still in operation. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac remain dispensing their guarantees to the housing market, noticed by the media only at the end of each quarter as they tote up their losses and demand further billions of the taxpayers’ money. The economically damaging subsidies to home purchase, diverting as they do scarce U.S. capital towards yet more unproductive housing, have just been extended both in time, for a further six months and in scope, to existing homeowners. The economic recovery, such as it is, appears to producing almost no jobs but only an ever-widening spiral in commodity prices, affecting the costs of everything the public consumes and eroding the value of its meager savings.

It’s not surprising given the new public taste for iconoclasm that the iconodules of both political parties have reacted with fear and alarm to Palin, who is no ideologue but through her background and style represents the strongest possible iconoclastic sentiment, opposed to Wall Street, Washington and all their doings. Her own political future is uncertain, as is her capability to take advantage of the new movement. But if she plays her hand cleverly, combining iconoclasm with political centrism, attracting good advisors while maintaining her anti-Washington following, her chances of a major political future at a national level would appear good.

With or without Ms. Palin, the iconoclast movement has substantial momentum. The current political-economic system is simply unsustainable; no economy can afford to pay for four giant zombie financial institutions, two substantial military adventures, a zombie-driven housing market, an exploding health-care bill and Goldman Sachs partners’ lifestyle aspirations. While the iconodules remain in charge, U.S. economic performance will consist of anemic growth punctuated by deep, grinding recessions, with new and small business starved of capital, which is instead sucked inexorably into the triple money pits of housing, the federal and state budget deficits and the investment-banking trading fraternity. In such circumstances, mere reform at the edges will not be enough; icons will have to be broken to liberate the U.S. economy from its excessive costs and allow new private sector growth sectors to emerge.

An icon-smashing president is probably likely to arrive before an icon-smashing Congress, given the electoral advantages to congressional incumbency. The U.S. economy must thus probably suffer at least another three years with the icons in place. Even a sharp 2010 congressional change would probably produce only legislative gridlock, although a belated conversion to iconoclasm by the Obama administration might produce change sooner. By 2013, the case for iconoclasm will be obvious to all. The current period of low interest rates and bubble creation will have met its inevitable sticky end, and the economic costs of unproductive icons will be fully apparent. The economy will be locked in an inflationary version of 1990s Japan, in which necessary reforms have not been taken and the detritus of old problems clogs up the streams of capital formation. At the same time, the costs of health-care reform will be looming close, and the tax increases necessary to move even partially towards balancing the federal budget will be hurting both taxpayers and the economy.

It will thus have become obvious that the housing market needs to be restored to a fully private market state, in which government subsidies are confined to the truly indigent. Zombie banks must be closed down, while the beneficiaries of “too big to fail” must be forced to slim down and divest operations until they are of a size where failure is conceivable. Commercial banks will simply become regional entities, whose failure would damage a regional economy but not the entire financial system. The trading behemoths will be broken into several competitors, whose market share will be too small for them to profit from “insider information” about market flows—a modest transactions tax will also reduce trading’s dominance. Home mortgages will once again be granted locally, with derivatives and securitization technology used only to prevent cost squeezes in high-growth areas. The obvious cost reductions in health care, eliminating the current system’s cross-subsidizations, will be legislated to reduce the sector’s oppressive cost growth. Public expenditure generally will be put on a strict diet, with expansionist foreign policy ended, both in its belligerent and its globalist forms. Finally, monetary policy will set interest rates at a level that rewards savers properly and prevents bubbles.

Iconodule vested interests will oppose such a program with all their strength. But in the end, the iconoclasts will win—the United States cannot economically afford for them to lose.

Martin Hutchinson is the author of “Great Conservatives” (Academica Press, 2005). Details can be found on the Web site www.greatconservatives.com.

© 2009 Prudent Bear

Andy Sieg, the head of Retirement & Philanthropic Services (RPS) for Bank of America Merrill Lynch who was hired in September from Citigroup by Sallie Krawcheck, president of Bank of America Global Wealth and Investment Management, has realigned his team, the bank reported yesterday.

RPS provides institutional and personal retirement solutions and comprehensive investment advisory and philanthropic services to individuals, small to large corporations, pension plans, endowments and foundations. RPS is responsible for over $450 billion in client assets. As part of this realignment:

Kevin Crain will run Institutional Client Relationships, responsible for institutional retirement business development and client relationship management for over 1,500 plan sponsors and four million participants. Crain is also responsible for oversight of legislative and public policy issues pertaining to retirement. Crain had run Plan Participant Solutions.

Aimee DeCamillo will run the Personal Retirement Solutions business, which will include Plan Participant Solutions, to help guide clients to an individual retirement platform provided by Merrill Lynch Global Wealth Management. DeCamillo, who reports to Sieg, will continue to serve as head of Personal Retirement, responsible for retirement education and planning, IRA products and rollover process, 401(k) plan participant solutions, 529 plans, health savings accounts, retirement income solutions and channel management.

David Roberts has rejoined Bank of America Merrill Lynch to run Equity Plan Services, the equity plan platform and the executive advisory services program, and the non-qualified deferred compensation platform. He will work with DeCamillo and others in GWIM to drive wealth management relationships within the equity plan business. The addition of Roberts is intended strengthen the business’ equity plan platform and infrastructure, considered a growth opportunity for GWIM. Bank of America Merrill Lynch serves more than 600 equity plans covering nearly 2.5 million participants in more than 100 countries, including 21 of the Fortune 125 companies, as of Sept. 30, 2009.

Other members of Sieg’s leadership team include: Paul Cummings, head of Institutional Investment & Advisory Services; John Furlong, head of Institutional Benefit Plans; Cary Grace, head of Philanthropic Management; Barry Lindenbaum, head of RPS Operations & Technology; and Kabir Sethi, head of Strategy & Institutional Business Office.

© 2009 RIJ Publishing. All rights reserved.

On its blog last week, the Financial Services Forum, a trade group, said its members want the Federal Reserve, not a new financial regulatory agency, to supervise large financial institutions.

FSF chairman is C. Robert Hendrikson, CEO of MetLife. Its members include the CEOs or other senior executives of AIG, Allstate, and Prudential Financial, as well as Goldman Sachs, Fidelity Investments, UBS AG, US Bancorp and other large financial institutions.

In endorsing the Fed, the FSF opposes Senate Banking Committee chairman Chris Dodd (D-CT), who has “proposed to create a single federal banking regulator out of the multiple agencies that now supervise them, including stripping the Federal Reserve and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. of their bank supervisory powers,” according to Politico.com.

Last Saturday, during a Senate hearing to consider Fed chairman Ben Bernanke’s re-appointment to another term, Sen. Dodd criticized the economist harshly for his assurances during 2008 that the sub-prime crisis was “contained” and by his failure to negotiate better terms for the government in bailing out AIG and its counterparties, notably Goldman Sachs.

The December 3 FSF blogpost said:

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, who faces what will most likely be a contentious re-confirmation hearing this morning, will no doubt be confronted with questions regarding the recent financial crisis, and what role the Fed, in its capacity as supervisor of large financial institutions, played in that crisis.

While the House Financial Services Committee passed a bill [December 2], by a vote of 31-27, which would expand the Fed’s role as a supervisor, Republican and Democratic members of the Senate Banking Committee reportedly agree on little else other than that the Fed should be stripped of all supervisory powers.

Senate Banking Committee Chairman Chris Dodd, last month, characterized the Fed as an “abysmal failure” in its duties as regulator of bank holding companies. The Committee’s Ranking Member, Richard Shelby of Alabama, has been quoted as saying that “all roads lead to the Fed,” regarding regulatory shortcomings. In addition, the Fed’s supervisory duties are seen as a distraction from its principle role as the monetary authority and the lender-of-last-resort, as Senator Dodd recently argued in an interview on CNBC.