Retirement plans cope better this year than in 2008-2009

More than 90% of employers will make their retirement plan contributions this year—a much better performance than in the 2008-2009 financial crisis, according to a new survey of retirement plan sponsors by the Plan Sponsor Council of America, a part of the American Retirement Association.

Nonetheless, 11.5% of plans with fewer than 50 participants changed their matching contribution. That’s more than three times the number of organizations with 5,000 or more participants, the survey showed.

Four times as many employers suspended or reduced their match during the 2008-2009 crisis than during the 2020 crisis, said Hattie Greenan, research director for PSCA, part of the American Retirement Association.

In 2008 companies that suspended their matching contributions experienced a decrease in plan participation to a much greater degree (72.9 percent of companies) than those that did not change their matching contribution (14.4 percent of companies), as well as a decrease in participant deferral rates.

“I think many [plan sponsors] went into this period expecting it wouldn’t last all that long, likely muting the potential impact on retirement savings,” said Nevin Adams, chief content officer and head of research for the American Retirement Association, in a release. “Mitigating factors, such as the recent broad-based government assistance in the form of the Payroll Protection Program, and have almost certainly helped as well.”

Relying on provisions of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act for permission to do so, more than half of the plans surveyed are allowing coronavirus-related distributions (CRDs). Nearly a third are allowing increased plan loan amounts. Half of plans are allowing participants to pause payments on existing loans that are due through December 1, 2020 and defer payments for up to a year. This is more common at large companies (73.3% of plans) versus smaller ones (23.1%).

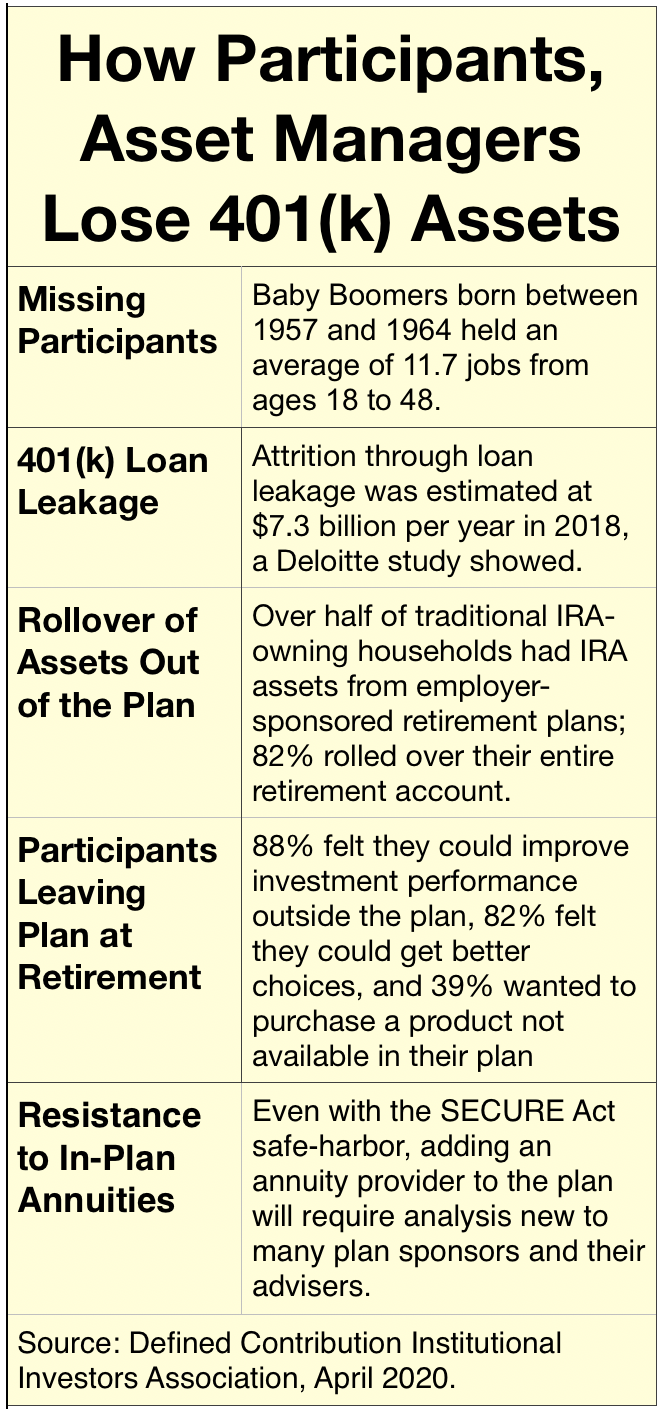

One in four plan sponsors reported a recent increase in plan loans, up from 13% of plan sponsors reporting an increase when survey five months ago. Nearly 40% of plans noted an increase in withdrawals since last summer. If only 10% of the roughly 600,000 employers suspended or reduced their contributions, the long-term impact on retirement security would be significant, the PSCA said.

PSCA surveyed plan sponsors in early November 2020 regarding their response to current conditions. The survey received responses from 139 companies that sponsor a 401(k) plan for employees. The full report is available at https://www.psca.org/research/cares_snapshot3

Public pensions have shown “great resiliency” this year: Milliman

The estimated aggregate funded ratio of the nation’s 100 largest public pension plans is 70.7% as of June 30, 2020, down from 72.7% reported in 2019, according to the results of the 2020 Public Pension Funding study by Milliman, the global consulting and actuarial firm. The study assesses the expected real return of each plan’s investments.

The aggregate Total Pension Liability reported at the last fiscal year-ends (for most plans, this is June 30, 2019) was $5.27 trillion, up from $5.07 trillion as of the prior fiscal year-ends, Milliman found. Between the 2019 and 2020 PPFS, over one quarter of the plans (28) lowered their interest rate assumptions, with 90 of the plans now reporting assumptions of 7.50% or below.

“While the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on public pensions’ financials is not fully clear, plans in this year’s PPFS experienced a huge swing in the estimated combined investment return, from -10.81% in Q1 2020 to 10.72% in Q2. More concrete evidence of the pandemic’s impact will be available once next year’s financial statements are published,” Milliman said in a release.

“Beyond market volatility, which has affected plan assets, we expect that furloughs and shutdowns as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic will impact pay levels and employee contribution amounts, while pressure on government budgets will make it hard to free up dollars to contribute to the plans to shore up their funding,” says Becky Sielman, author of the funding study.

“But public plans have, by and large, shown great resiliency. They are designed and financed to function over a very long time horizon, and can take short-term setbacks in stride.” The full Milliman 100 Public Pension Funding Study can be found at http://www.milliman.com/ppfs/.

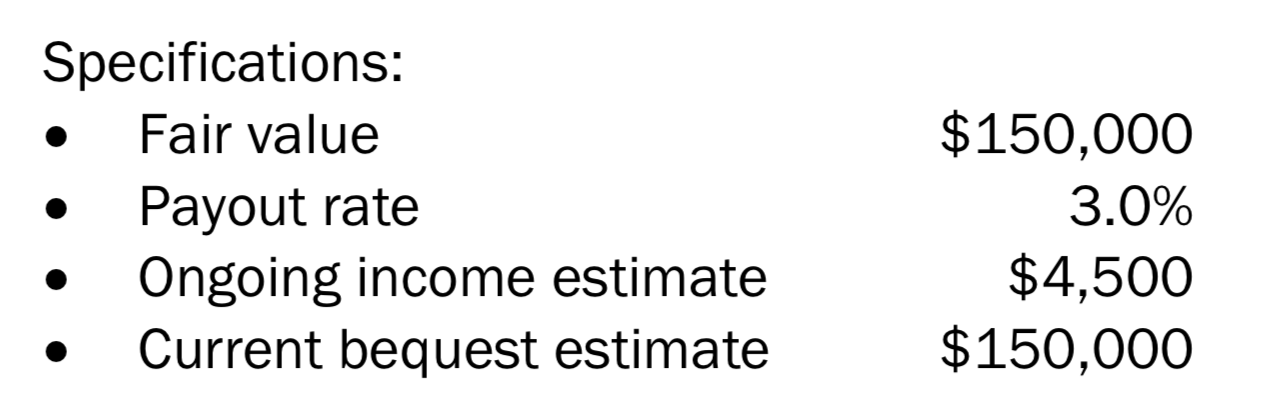

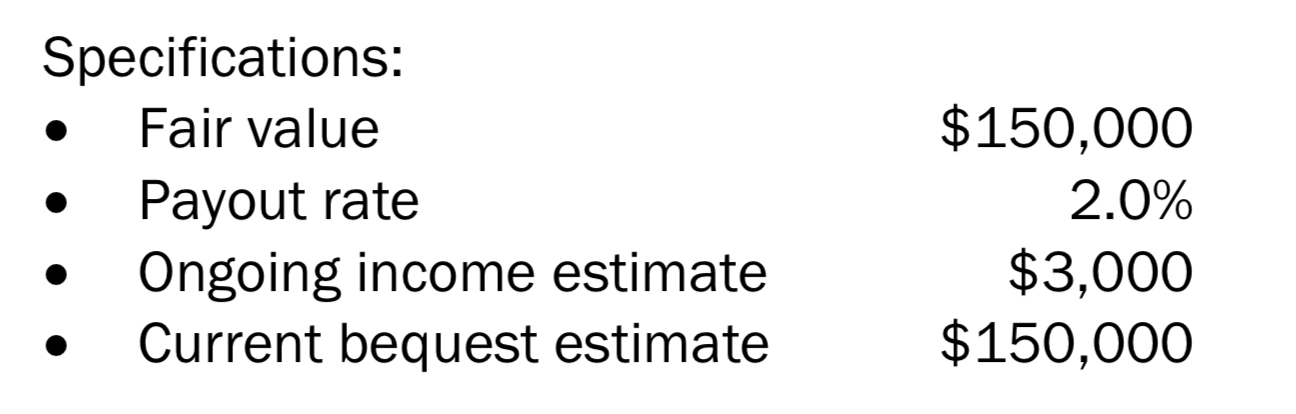

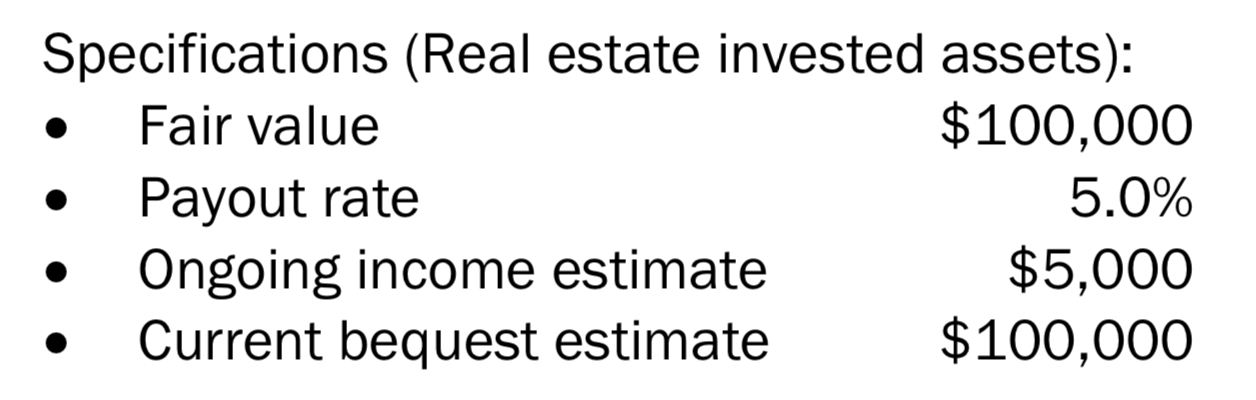

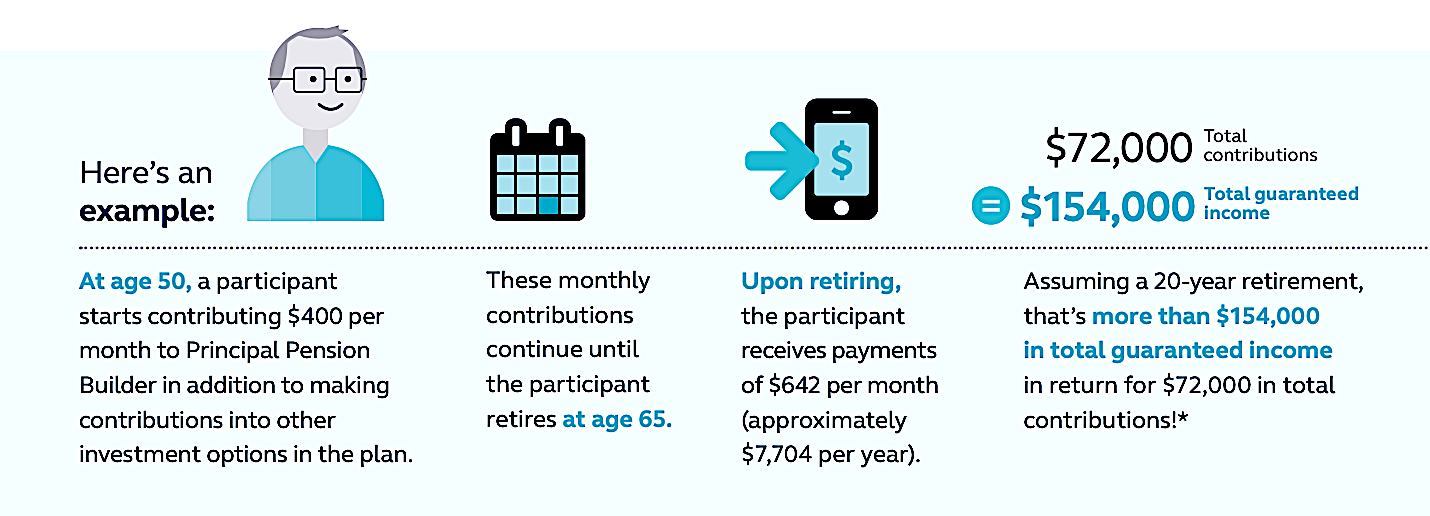

TruChoice to distribute Jackson National annuities to RIAs

TruChoice Financial Group, LLC, an insurance products distributor, and Jackson National Life Insurance Company(Jackson) have announced distribution deal that will bring Jackson’s no-commission annuities to fee-based advisers through TruChoice’s Outsourced Insurance Division, according to a release this week.

“The OID distribution model utilizes a product-agnostic, multi-carrier methodology to allow financial professionals to manage client assets and protection needs while working with FINRA-registered and insurance-licensed OID Specialists,” the release said.

Like Jackson, TruChoice has a presence on FIDx, which powers the Envestnet Insurance Exchange and MoneyGuide Protection Intelligence. Three of Jackson National’s fee-based products are now available to RIA firms and IARs through TruChoice’s OID platform: Perspective Advisory II and Elite Access Advisory II (both variable annuities) and MarketProtector Advisory, a fixed indexed annuity.

SPARK Institute elects new chair and vice-chair

The SPARK Institute, a trade association of retirement plan recordkeepers, announced that Ralph Ferraro, SVP, head of Product and Solutions Management, Lincoln Financial, has been elected chair of its Governing Board.

He succeeds Rich Linton, EVP Group Distribution and Operations, Empower Retirement, who has completed his term. Linton has been the chair since 2017 and will remain as an active member of the board. Kevin Collins, head of Retirement Plan Services, T. Rowe Price, has been elected as vice chair.

The SPARK Institute’s governing board includes twelve firms: AIG, Ameritas Life Insurance Corp., Ascensus, BlackRock, Empower Retirement, FIS Global, J.P. Morgan Asset Management, Lincoln Financial Group, Prudential Retirement, SS&C, T. Rowe Price and Wells Fargo Institutional Retirement.

Pandemic shows importance of 401(k) “sidecar” accounts: Morningstar

Observing that many retirement plan participants have felt compelled to tap their 401(k) savings this year for hardship withdrawals or loan, Morningstar’s head of policy research argues in favor of creating so-called sidecar accounts that workers can use for emergency withdrawals while leaving their long-term savings intact.

In “Harnessing the Power of Defaults to Save for Emergencies,” Aron Szapiro writes, “Sidecar accounts probably would not provide enough of a cushion for many workers affected by COVID-19. A large scale social safety net, like unemployment insurance, needs to be available for massive macroeconomic disruptions.

“But the government’s COVID-19 response and workers’ behavior in response to it, shows the promise of sidecar accounts for more pedestrian emergencies… Many people would likely accept a sidecar program alongside their 401(k) as their default savings setup. These accounts, once filled from default contributions, would be largely preserved for bona fide emergencies.”

Drawing from 401(k)s represents a significant drag on workers retirement savings, according to the US Government Accountability Office. The GAO estimated that around $70 billion leaks out of the retirement system every year. “Workers would not tap their 401(k) accounts if they absolutely did not have to, given the evidence we see from the post-CARES act withdrawals,” Morningstar has found.

Solash takes on new responsibilities at AIG

AIG Life & Retirement, a division of American International Group Inc. (NYSE: AIG), today announced that Todd Solash, CEO of its Individual Retirement business, will also lead the company’s Life Insurance business, effective immediately.

As CEO, Individual Retirement and Life Insurance, Solash will be responsible for the division’s strategic agenda. He joined AIG in 2017 from AXA US where he was head of the firm’s individual annuities business.

Before that he was a partner within the Insurance practice at Oliver Wyman, a management consultancy. Solash has bachelor’s degrees in Finance and Chemical Engineering from the University of Pennsylvania and is based in Woodland Hills, California.

© 2020 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.