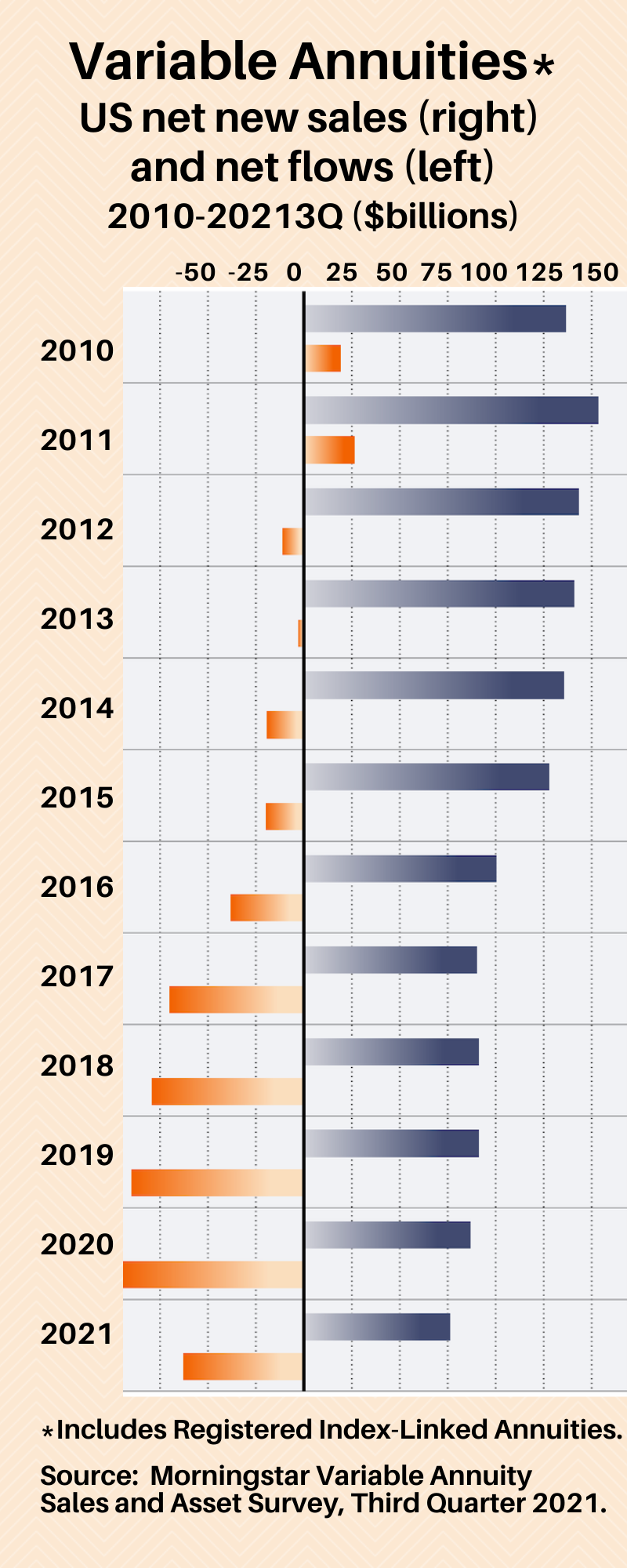

For much of the first decade of the 21st century, leading publicly traded US life insurance companies had reason to believe that their flagship product would help then capture the multi-trillion dollar Boomer retirement opportunity.

That product was the deferred variable annuity with a guaranteed lifetime withdrawal benefit, or VA/GLWB for short. It was profitable, and it gave aging Boomers what they wanted: stock market exposure and access to their money, plus protections against longevity and mortality risk.

Then came NAIC regulation AG 43, the stock market crash of 2008, and the Federal Reserve’s low interest rate policy. Some life insurers, squeezed by higher capital requirements and lower yields, sought and found relief through “captive reinsurance.”

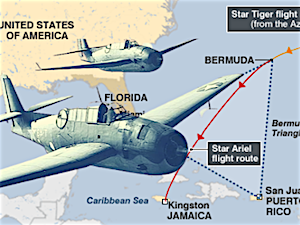

More than a decade later, academics are still trying to analyze and interpret the dynamics of that turning point in life/annuity history. A recent research paper, “Accounting Rule-Driven Regulatory Capital Management and its Real Effects for US Life Insurers,” represents a recent dive into the data. Their work supports recent RIJ articles on the “Bermuda Triangle strategy.”

The article shows that the drop of equity values in 2008 and AG 43 triggered a giant margin call for life insurers with large VA books, motivating the insurers to offset a spike in capital requirements by purchasing reinsurance. Sehwah Kim and Qingkai Dong of Columbia University and Steven Ryan of New York University wrote the article.

The life insurers purchased the reinsurance from themselves. Instead of, or in addition to, raising new capital, some issuers transferred liabilities to their own internal “unauthorized captive reinsurers,” as regulators defined them. This brought the parent companies’ capital requirements back down, which, in effect, enabled them to keep selling VAs without adding new capital.

Some regulators frowned on this practice, calling it “shadow insurance.” The accounting maneuver didn’t break the law, but it relied on “regulatory arbitrage”—i.e., locating the captive reinsurer in a state or country with less stringent capital requirements than the home state of the life insurer. It was cheaper to set up captive reinsurance than raise fresh capital.

“To engage in shadow insurance, parent operating insurers establish unauthorized captive reinsurers that face lax regulation (e.g., are minimally capitalized and not required to file SAP-based financial statements or to satisfy SAP-based risk-based capital requirements),” wrote the authors of the paper. [SAP refers to Statutory Accounting Principles, which every US life insurer must use. Some jurisdictions allow use of less stringent Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, or GAAP.]

The paper shows that big VA issuers, who were most affected by AG 43, were most likely to respond with captive reinsurance. They were much “more likely to cede insurance to unauthorized captive reinsurers subject to lax regulation… after the [2008] shock,” than other insurers, the authors found.

The paper includes diagrams and sample balance sheets that illustrate how shadow insurance can work. The diagrams help illuminate the “Bermuda Triangle strategy” that large asset managers currently use to reduce the capital demands on life insurers they own or partner with. The strategy relies on the use of reinsurers domiciled in jurisdictions with GAAP-based regulations, such as Bermuda or the Cayman Islands.

Here are summaries of four more research papers we found pertinent to retirement finance:

“Education and Income Gradients in Longevity: The Role of Policy,” by Adriana Lleras-Muney, UCLA. NBER WP29694, January 2022.

Wealthier people live longer, on average, than poorer people. Possible explanations for that fact come easily to mind. But this paper’s author discovered when reviewing past research on this topic, no clear causal link between wealth and health has ever been found.

While “income is a strong predictor of mortality,” UCLA’s Adriana Lleras-Muney wrote, “there is no constant or necessarily structural relationship between income and health.”

Where a person lives and when a person achieves wealth can affect their health, she found. For instance, poor people in wealthy states tend to live longer than poor people in poor states. And poverty during vulnerable periods of life—like early childhood or advanced age—correlates with mortality.

“Mortality has fallen in states with high incomes only because in recent time these states have chosen to implement policies that improve the health of its most vulnerable populations,” the author writes. The author found that income transfers to poor mothers of small children increase the future health of the children.

The impact of winning a state lottery has varying impacts, according to the paper. The effects depend in part on whether the new millionaire used the money to move to a healthier neighborhood and to acquire better health care, and whether the money was received early enough in life to alter the trajectory of personal health.

“Aging and Welfare-State Policy: Macroeconomic Perspective.” Assaf Razin, Tel Aviv University, and Alexander Horst Schwemmer, Ludwigs-Maximilians-Universitat, Munich. NBER Working Paper 29700, January 2022.

Pension financing, trade policy, and immigration are all hot-button issues, not just in the US but also in many other prosperous “welfare states” with growing populations of elderly and declining birth rates. The authors of this paper, from Israel and Germany, show that those issues are related.

For instance, as a country’s population ages and the ratio of non-workers to workers rises, pressure to raise taxes on the working population tends to rise. To ease that burden—and instead of simply printing or borrowing more money—the country has to get richer (by importing more capital) or younger (by accepting more immigrants).

But how does a nation’s government choose—assuming its public institutions make public policy—the optimal balance of social spending on elderly care, and taxation of capital and labor, and legal immigration? The authors introduce a model for mixing the relevant variables and distilling useful policy recommendations.

They conclude that policy depends on who makes it—regardless of whether the nation is aging or not.

“If the rich are in charge of the migration policy making, in both the high-aging state and the low-aging state, they are biased towards relying on low-skill migrants,” they write. “If the poor are in charge of the migration policymaking, in both the high-aging state and the low-aging state they are biased towards relying more on high skill migrants.”

The rich don’t feel a threat to their job security from a rising number of low-skill migrants; on the contrary, it increases the base for taxing labor. The poor don’t fear rising taxes on their capital gains because they generally don’t have them; the rich do.

“Long-term Care Insurance Financing Using Home Equity Release: Evidence from an Online Experimental Survey.” Katja Hanewald, Hazel Bateman, and Tin Long Ho of the University of New South Wales, and Hanming Fang of the University of Pennsylvania. NBER Working Paper 29689, January 2022.

Like Americans, many Chinese hold much of their personal wealth in the form of their own homes. Also like many Americans, middle-class Chinese hesitate to buy long-term care insurance (LTCI) and would prefer to age in their own homes.

A group of economists from the US and Australia has proposed a program that would allow the Chinese to use home equity to buy a form of LTCI that would pay for institutional care or at-home care.

The Australian researchers are familiar with two kinds of home equity release. Those are reverse mortgages, which are also available but not widely used by retirees in the US, and home reversion, which is available in Australia through a program sponsored by the government.

In a reverse mortgage, a retiree buys an income annuity with the proceeds of a loan against their home equity, or sets up a line of credit using their home equity as collateral. When the borrower sells the home or dies, the reverse mortgage company recoups the loan from the proceeds of the sale, with interest. In a home reversion, the homeowners sell part of their housing wealth, receive a payment upfront, lease their homes from the mortgage company, and also receive a proportional share of the sale proceeds when they die or move out.

Using data from an online experimental survey fielded to a sample of 1,200 Chinese homeowners aged 45-64, the authors assess the potential demand for new financial products that allow individuals to access their housing wealth to buy long-term care insurance.

“We find that access to housing wealth increases the stated demand for long-term care insurance. When they could only use savings, participants used on average 5% of their total (hypothetical) wealth to purchase long-term care insurance,” they write.

“When they could use savings and a reverse mortgage, participants used 15% of their total wealth to buy long-term care insurance. With savings and home reversion, they used 12%. Our results inform the design of new public or private sector programs that allow individuals to access their housing wealth while still living in their homes.”

In 2014, a reverse mortgage program (the “House-for-Pension” program) was introduced in several large cities in China. Uptake of the pilot program was low, but the authors saw signs of demand for simpler and more flexible reverse mortgage products. One complication in China: many of the people who own their own homes do not own the land under the homes.

“Cognitive Decline, Limited Awareness, Imperfect Agency and Financial Well-Being,” by John Ameriks, Vanguard; Andrew Caplin, New York University; Minjoon Lee, Carleton University; Matthew D. Shapiro, University of Michigan; and Christopher Tonetti, Stanford University. NBER Working Paper 29634. January 2022.

When we lose our wits in old age, we don’t notice it right away. So we tend to go on making personal financial decisions for longer than we should. That’s when we’re most likely to get scammed or make a big mistake.

To study this phenomenon, a team of economists from Vanguard and four major universities recently surveyed older Vanguard shareholders about their expectations, worries or preparations for their own potential cognitive decline.

While the survey subjects generally agreed that it would be ideal to yield control of their finances to an adult child before their decline began—but no earlier. But it was also clear that the elderly can’t tell exactly when cognitive decline starts.

About 2,500 people participated in the study, with an average age of 74. All were over age 55 and 80% were between the ages of 64 and 83. All had at least $10,000 in investments at Vanguard. Their median financial wealth was $1 million or more and 76% had a college degree. Most (70%) said they would assign supervision of their finances to an adult child if the need arrived.

When asked to estimate the potential dollar-cost of making a financial mistake before they noticed their own decline, the shareholders on average estimated a potential loss of about 18% of their financial wealth (a loss of about $400,000, or 18% of about $2.22 million).

Of those surveyed, 25% said they would be willing to pay more than $50,000 and 15% were willing to pay more than $100,000 to guarantee the optimal timing of the transfer of the management of their financial affairs to a family member or professional.

The economists did not suggest a solution to such a dilemma or a product or service to respond to such a demand. They merely demonstrated the existence and prevalence of this anxiety among the affluent elderly. “This transfer-timing issue is a serious concern for many older American wealthholders,” the economists found. The participants in the survey broadly believed that they were the best managers of their finances if they were mentally healthy, but the worst possible managers if they weren’t.

© 2022 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.