Source: IMF Global Debt Database.

IssueM Articles

Source: IMF Global Debt Database.

If you’re into high-end auto components, you may be familiar with Recaro seats. You may also be acquainted with Brembo disk brakes and ZF nine-gear automatic transmissions. Drew Carrington would like you to think about Franklin Templeton’s 401(k) funds in a similar vein.

Carrington is a senior vice president at Franklin Templeton Investments, where he leads the distribution of that firm’s actively managed funds through $1 billion-plus defined contribution plans. His job is to convince plans sponsors and their consultants that his company’s funds should be among the investment options they offer their participants.

Drew Carrington

He’s been spreading the word that large 401(k) plans should include a “retirement tier” reserved for participants who are nearing retirement. As participants age into this tier, they would receive new kinds of pre-retirement advice and have access to products that could help them transition from the accumulation phase to the decumulation phase.

Not coincidentally, Franklin Templeton has funds that can fill the retirement tier like fingers in a glove. Along with its Franklin Income Fund, which distributes interest and dividends, the company offers the LifeSmart Retirement Income Fund, which generates monthly paychecks, and Franklin Retirement Payout Funds, which lets participants schedule payouts up to five years before they retire.

But the current trends are not Franklin Templeton’s friends. Plan sponsors have been shrinking their fund lineups and, like investors, switching to index funds. Moreover, many plan sponsors do little to help retired participants keep their money in the plan (rather than rollover to an IRA) and draw regular income from their accounts.

The damage to Franklin Resources, the parent of Franklin Templeton Investments, has been acute: In the year ending April 2018, its funds saw net outflows of almost $28.7 billion (about 7.7%). Since the end of 2014, the Franklin Resources share price has lost about 40% of its value.

One tier, four elements

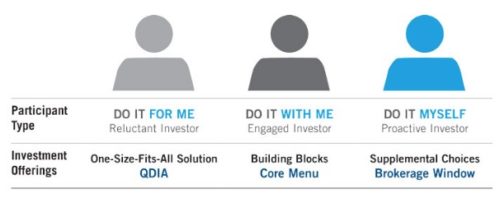

“‘Retirement Tier’ is an idea that we’ve been out in the market talking about,” Carrington told RIJ recently. “The word ‘tier’ is a shorthand way of describing groups of participants. On each tier you have certain participants and certain investments that are appropriate for each. The tiers typically refer to participants who either want the plan provider to ‘Do it for me,’ or ‘Do it with me,’ or who say, ‘I’ll do it myself.’

“A ‘Retirement Tier’ would be more than that,” he said. “We see it as having four characteristics. First, we think a plan should allow for partial ad hoc withdrawals for people who are over age 59½ and are separated from service. Today that type of person can only take a lump sum withdrawal, or execute a cash-out rollover or they can get one shot at setting up systematic withdrawals. Once you set up withdrawals, you can’t change your decision except to take a lump sum.”

“The second feature of a Retirement Tier would involve targeted communications for participants approaching retirement. There are many opportunities to engage these them. There are milestone birthdays, such as when they turn 50 and become eligible to make ‘catch-up’ contributions. The third piece involves providing coaching, models, or tools, such as a Social Security Optimizer.

“The final piece, which we think is especially important, is to offer a set of investments that are appropriate for retirees or near-retirees. It might be annuities. It might be income-focused investments, or managed payout funds. But it might also mean a broader set of tools on the fixed income side. You would not want to restrict the options to merely an aggregate bond fund or an asset preservation fund.”

Fund options for the retirement tier

If you surf over to the Retirement Income Solutions page of the Franklin Templeton website income generating funds on its website you find three:

Franklin Income Fund. This $77 billion fund ($2 billion in R6 retirement plan shares), which turns 70 years old this August, has an allocation of about 40% bonds and 40% dividend paying stocks. The rest is mainly in convertible bonds and cash. Almost all of its bonds are rated BBB (9%) or non-investment grade (87%). Institutional R6 shares have an expense ratio of 0.40%.

Franklin LifeSmart Retirement Income Fund. Created in 2006, this fund is a fund of Franklin Templeton funds with a gross expense ratio of 0.97% and a net expense ratio of 0.44% for R6 shares. It has only $3.8 million in R6 shares and $56.3 million total. With an asset allocation of 60% bonds and 40% stocks, it invests in Franklin U.S. Government Securities Fund, Franklin Floating Rate Daily Access Fund, Franklin Income Fund, Templeton Global Total Return Fund, Franklin High Income Fund and outside funds.

Franklin Retirement Payout Funds. Launched in mid-2015, this series of funds enable investors to build the equivalent of a bond ladder out of a series of target-date bond funds, each designed to distribute all of its principal and interest in the target year. The funds invest in U.S. dollar-denominated investment grade fixed income securities and in U.S. dollar-denominated foreign securities. Their institutional share annual expense ratio is 0.30%.

Carrington compared Franklin Templeton to the suppliers of specialty parts for high-performance cars. “The final assembly of an automobile is labor-intensive. It’s a tough business to be in. But think about companies that make specific high quality component parts: the Recaro seats, Brembo brakes, or ZF transmissions. Those companies are less labor-intensive, and they have higher profit margins. I would say, ‘We make really good transmissions and really good brakes.’”

‘Nobody wins that way’

While Carrington’s interest in promoting his funds is a narrow one, there’s fairly broad agreement in retirement income circles that retooling 401(k) plans should be updated to reflect their evolution into de facto replacements for defined benefit plans as the principal private source of retirement income for American workers.

Just this week, Kelli Hueler, the founder of IncomeSolutions, a web platform where individual investors can buy annuities from competing life insurers, testified at an ERISA Advisory Committee meeting on this topic. She urged the Department of Labor to revise its 22-year-old Interpretative Bulletin 96-1 so that plan sponsors can educate participants about decumulation and offer partial withdrawals for retired participants.

“Obviously, plan sponsors have been reluctant to provide any guaranteed solution,” Carrington told RIJ. “But they’ve also been reluctant to add additional options. The idea of a Retirement Tier sounds at first like it runs counter to the overall goal of plan simplification. But we would argue that you can communicate it in ways that make things less confusing. We’re talking about a full set of tools—changes in plan design, communication and technology tools—that help people close to retirement.

“Just offering investments in a vacuum without tools—that doesn’t achieve anybody’s objectives. But if you provide the context, and you make it more likely that sponsors will adopt them and that participants will use them, then you have better outcomes. We want to talk about what we do as part of a bigger picture.”

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

This was a talkative week in Washington, D.C. for folks who want the Department of Labor to tweak (or refrain from tweaking) the 401(k) system to reflect its emergence as American’s primary source of private retirement savings in a post-defined benefit pension world.

On Tuesday, Kelli Hueler of IncomeSolutions, the online annuity platform for plan participants and others, and Jack Towarnicky, director of the Plan Sponsor Council of America (now part of the American Retirement Association), both testified at a meeting of the DOL’s ERISA Advisory Council.

On Wednesday, the Employee Benefit Research Institute held a broadcast webinar on the findings of its Retirement Security Projection Model. Jack VanDerhei presented and Brett Hammond, the American Funds research chief and former TIAA executive, moderated.

Lots of issues are in the air: some new, some evergreen. Up to half of private-sector workers don’t have a tax-deferred retirement savings plan at work. The cost and quality of plans varies widely, depending on employer size and profitability. Too many workers still reach retirement without enough savings. Few plans teach workers how to convert 401(k) accounts into personal pensions.

The wild card factor for 401(k) plans has been the emergence of the rollover IRA. Trillions of dollars accumulate in 401(k) accounts, but when workers change jobs or retire, they move their account assets into rollover IRAs. As a result, individual brokers and financial advisors are replacing 401(k) sponsors as the proximate provider of income counseling. Reasonable people disagree on whether that’s a positive development.

‘Change IB-96’

Kelli Hueler

Hueler would like to see sponsors play a bigger role in income counseling. An entrepreneur who runs a respected stable-value data business, she has also barnstormed the nation for over a decade, enlisting support from jumbo plan sponsors like IBM, GM and Boeing for her IncomeSolutions web platform, where recently-separated plan participants can roll part of their savings into an immediate or deferred income annuity.

Hueler wants to change the 401(k) rules that currently discourage the conversion of savings to income. She urges the DOL to revise the language about participant education in a 22-year-old directive, Interpretive Bulletin 96-1, to “specifically address the decumulation phase” and highlight, among other things:

“The attributes of partial withdrawals in order to encourage plans to offer partial distributions, so participants may retain a portion of their savings in the plan as well as take advantage of institutionally structured and priced lifetime income alternatives and purchasing strategies.”

‘No new mandates’

Towarnicky presented testimony on behalf of the PSCA, which, until fairly recently, was called the Profit-Sharing Council of America. Members of the PSCA have no great desire to retool their plans to make them more defined benefit-like, nor, they say, are participants demanding such a change. He acknowledged a need to make it easier for retirees to draw regular income from plan accounts, but otherwise he thinks the status quo is working.

Jack Towarnicky

“Many plan sponsors use decumulation processes other than annuities to accommodate diverse participant demographics,” he said. “Because lump sum/installment payouts offer greater flexibility with less complexity and cost, they offer value to many more participants. Adding in-plan retirement income features are typically not top priorities as participants can customize retirement income by using the more than adequate decumulation/ retirement income products/options available in the IRA marketplace.”

Above all, plan sponsors don’t want government mandates and they want to avoid any activities—adopting in-plan annuities, recommending annuities, illustrating lifetime income—that might get them sued by participants down the road.

EBRI’s super modeling tool

In its webinar yesterday, EBRI, which compiles data on defined contribution plans, rolled out the latest findings of its Retirement Security Project Model. EBRI uses this tool to assess retirement policy proposals. Recently, EBRI assessed America’s retirement readiness and evaluated the following potential initiatives:

Evaluations of these proposals from the RSPM analysis included:

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Bank of America Corp’s Merrill Lynch Wealth Management is reconsidering an internal policy from 2017 that banned advisers from opening new retirement accounts that paid them commissions, according to a source familiar with the situation, Reuters reported this week.

Merrill Lynch, along with JPMorgan Chase & Co, moved away from brokerage retirement accounts last year, banning the opening of new ones and moving many clients into advisory accounts, in preparation for the U.S. Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule.

The fiduciary rule, an initiative of the Obama administration, was intended to curb conflicts of interest for financial advisers, especially when accepting third-party commissions on the sale of equity-linked annuities to rollover IRA clients. The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals vacated it in March.

Merrill Lynch head Andy Sieg told brokers on a conference call on Friday that the firm had launched a 60-day review of its individual retirement account policies and will consider keeping, relaxing or rolling them back, the source said.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

At the end of May, the International Monetary Fund launched its new Global Debt Database. For the first time, IMF statisticians have compiled a comprehensive set of calculations of both public and private debt, country by country, constructing a time series stretching back to the end of World War II. It is an impressive piece of work.

The headline figure is striking. Global debt has hit a new high of 225% of world GDP, exceeding the previous record of 213% in 2009. So, as the IMF points out, there has been no deleveraging at all at the global level since the 2007-2008 financial crisis. In some countries, the composition of debt changed, as public debt replaced private debt in the post-crisis recession, but that shift has now mostly stopped.

Are these large figures alarming? In aggregate terms, perhaps not. At a time when economic growth is robust almost everywhere, financial markets are relaxed about debt sustainability. Long-term interest rates remain remarkably low. But the numbers do tend to support the hypothesis that the so-called debt intensity of growth has increased: we seem to need higher levels of debt to support a given rate of economic growth than we did before.

Perhaps that is partly because the growth in income and wealth inequality in developed countries has distributed spending power to those with a propensity to spend less than their income. That trend has leveled off recently, but the implications are still with us. It also seems that productivity growth has slowed, so a given quantum of investment generates less output than it used to do.

The IMF’s recommendation to governments is that they should fix the roof while the sun is shining: accumulate a fiscal surplus, or at least reduce deficits, in good times so that they are better prepared for the next downturn, which will surely come before too long. The current upturn is now quite mature.

That puts the IMF on a collision course with the tax-cutting United States administration and now with Italy’s new government. If the Italians’ grandiose plans for a minimum income and more public investment are implemented, they might soon find themselves in difficult discussions with the Fund. The team that has been in Athens for the past few years might soon be booked on a flight to Rome.

But what are the implications if the growth in debt is principally in the private sector? That is a question for the financial stability authorities in each country.

Since the crisis, new, far tougher capital requirements have been introduced for banks, and a set of macroprudential tools has been developed for regulators.

The idea is that regulators should be able to “lean into the wind” of excessive credit expansions, by increasing the amount of capital a bank must hold, with the aim of dampening the supply of credit before it reaches a dangerous level. The increase might be imposed across the board, or focused on mortgage lending, for example, if growth in house prices looks worryingly rapid. Other alternatives could be to impose maximum loan-to-value limits, or minimum down payments on home purchases.

New authorities were established to oversee the use of these new macroprudential tools. The European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB), chaired by European Central Bank President Mario Draghi, does the job in the European Union, and the Financial Policy Committee (FPC) of the Bank of England has domestic jurisdiction in the United Kingdom, though the Governor of the Bank of England is also Deputy Chair of the ESRB. (What will happen to that position after Brexit is unclear.) In the US, the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) is the coordinating body.

But there are important differences between them. The FPC is in some ways the most powerful of the three. It can impose a countercyclical capital buffer on UK banks, and has at times threatened to do so. For a time, the Committee took the view that unsecured personal lending was growing too fast.

The ESRB cannot act discretely, but it monitors EU and EFTA member states closely and publishes regular reports. The most recent review, last month, showed that additional buffers are in force in Sweden, Norway, Iceland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia, in response to the particular credit conditions in those countries. France has since joined the list. In the eurozone of course, the ECB is the supervisor, so Draghi can put on a different hat and act directly, if necessary, through his own staff.

The US position is less clear. The FSOC is a coordinator, not regulator with its own powers. It is a bowl in which the alphabet soup of US financial regulators is stirred from time to time. It has no authority over its members and cannot impose countercyclical buffers. Its attempts to categorize large US insurers as globally systemic firms have been thwarted by the courts. There are those at the US Federal Reserve who wish it were otherwise, recognizing that without the support of the FSOC, which is chaired by the Treasury Secretary, they will find it hard, if not impossible, to dig into the macroprudential toolkit.

We must hope, therefore, that the Basel-based capital requirements imposed by the various US banking regulators are adequate. So far, the ratios have not been cut,

though other deregulatory initiatives, proposed by Trump appointees in the relevant agencies, are in the works. Macroprudential policy may be working as intended in Slovakia, but it is unlikely to come to the rescue where it needed the most: in the world’s biggest financial market.

Howard Davies, the first chairman of the United Kingdom’s Financial Services Authority (1997-2003), is Chairman of the Royal Bank of Scotland. He was Director of the London School of Economics (2003-11) and served as Deputy Governor of the Bank of England and Director-General of the Confederation of British Industry.

© 2018 Project Syndicate.

Demand for equity funds that invest primarily outside of the U.S. has been gradually diminishing since January, and flows have turned outright negative in June, according to TrimTabs, a research firm.

Global equity funds have shed $6.8 billion this month through Friday, June 15, putting them on track for their highest monthly outflow since at least September 2016.

Global equity funds have trailed their U.S. counterparts in four of the first six months of the year. They are down 0.9% year-to-date, while U.S. equity funds have gained 5.6%.

Breaking flows down, global equity mutual funds have lost an estimated $2.1 billion in June, on track for their first outflow in 15 months. Global equity ETFs shed $4.3 billion in May, their first outflow in 1½ years, and they have redeemed an additional $4.8 billion in June.

All major international regions have had outflows this month except for China, even though Chinese stocks have made no headway for months. China equity ETFs have added $400 million (1.9% of assets) in June, with inflows on all but one trading day, even though they are up a scant 0.2% month-to-date.

Despite the harsh rhetoric about China from President Trump since he took office, China-focused equity funds are on track for their sixteenth consecutive monthly inflow.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

The Spring 2018 edition of the Journal of Retirement has appeared. Here’s a list of its contents and abstracts of its articles.

Editor’s Letter, by George A. (Sandy) Mackenzie

Predicting Longevity: An Analysis of Potential Alternatives to Life Expectancy Reports, by Jiahua Xu and Adrian Hoesch

This research offers a new conceptual model for estimating longevity: a two-factor-Longevity Estimation-analysis model with a telomere test as a medical basis (physiological factors) and a big data approach to filter the psychological factors to longevity. This model, together with existing LE-projection methodologies, could improve LE predictions, the authors write. Inaccurate estimation of longevity–due primarily to misinterpretations of the influence of resilience factors on longevity– harms retirees, pension funds, and the insurance industry, they assert.

Beyond the Glide Path: The Drivers of Target-Date Fund Returns by David Blanchett and Paul D. Kaplan

An assessment of the riskiness of any target-date fund (TDF) must be based on more than the size of its allocation to equities, these authors claim. They examine three drivers of target-date fund (TDF) performance: equity (or market) exposures over time (the glide path), style exposures within asset classes (intra-stock and intra-bond allocations), and other factors (e.g., manager selection and the active/passive decision, as well as any other residual risk exposures). Equity exposure drives only about 25% of the variation in returns across TDFs while style drives about 30% and selection drives about 45%, they found.

Making a Complex Investment Problem Less Difficult: Robo Target-Date Funds by Jill E. Fisch and John A. Turner

Fisch and Turner propose that target-date funds (TDFs) be personalized by offering retirement plan participants a conservative, moderate, and risky fund for each target date. They also suggest that pension plans incorporate robo advisers to help each participant identify his or her appropriate level of risk and appropriate target-date fund. Finally, they propose on-the-spot financial education to help participants understand the implications of each risk level. “The current one-size-fits-all approach generally does not provide the appropriate level of risk for all employees who plan to retire in a given year,” the authors claim.

Replacing the Failure Rate: A Downside Risk Perspective, by Javier Estrada

The author proposes “downside risk-adjusted success (D-RAS) as an improved method for evaluating retirement strategies. D-RAS takes a downside risk perspective, measuring risk with the semi-deviation and, therefore, with volatility below a chosen benchmark. At present, risk evaluation is typically based on the failure rate (the rate at which a retiree’s nest egg is exhausted prematurely), or risk-adjusted success (RAS), which aims to capture the failure rate and the success of the strategies evaluated. RAS penalizes strategies that leave large bequests, however. D-RAS addresses this shortcoming.

Six Key Influences on the Efficiency of In-sourcing in State and Local Plans, by

Michael A. Urban

State and local pensions can take care of the investment function in-house, or they can outsource part or all of it. Which strategy is the more desirable depends on six key influences that vary across institutions: the behavior of cash flows, the significance of economies of scale, asset allocation, staff compensation, a plan’s geographic location, and the scope of fiduciary duty and oversight. This article offers a way to think comprehensively about in-sourcing in the context of local politics and regulation, governance, and geography.

To What Extent Does Socioeconomic Status Lead People to Retire Too Soon? by Alicia H. Munnell, Anthony Webb and Anqi Chen

Working longer enhances retirement security, but the most vulnerable individuals–those with low socioeconomic status (SES), poor health, and/or poor job prospects– can’t always work longer, these authors write. Using data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), they show that people who most need to work longer tend to face the biggest barriers to working longer. The correlation existed even after the authors controlled for household characteristics and late-career shocks. They may need other solutions to their retirement savings gaps.

Governments Have It Wrong on Pensions—Personal Lessons from a Consulting Career, by Michael Littlewood

Governments and employers should stay away from subsidized or forced saving schemes, writes this author. He asserts that: Only governments can a) eliminate or reduce poverty in retirement through a universal state pension; b) level the tax and regulatory playing fields for all financial services; c) obtain high-quality data to assess what households are doing about their retirement incomes; d) deliver believable information that helps citizens to understand their retirement saving needs. There is no evidence that subsidized or forced savings programs have worked anywhere in the world, he writes.

Book Review: “The Little Book of Common Sense Investing: The Only Way to Guarantee Your Fair Share of Stock Market Returns (10th edition),” by Jack Bogle.

Reviewed by George A. (Sandy) Mackenzie

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Nationwide plans open a new 31,000-square-foot innovation center in the Arena District, according to a release issued this week. The company plans to renovate space within the building at 175 W. Nationwide Blvd., owned by Nationwide Realty Investors and its partner, Capital Square Ltd. The company is also planning to add several dozen jobs to support its innovation programs.

Nationwide expects to run out of space in its existing innovation center, Refinery 191, by the end of this year. Nationwide will eventually move all the work from Refinery 191 to the highly collaborative new innovation center, which is scheduled to open in 2019.

Last August, Nationwide announced its commitment to drive more innovation that helps members:

Along with the space expansion, Nationwide plans to hire several dozen highly skilled workers for innovation roles in Columbus over the next year. Nationwide will also move its user-experience (UX) team to the new center.

Nationwide is also investing more than $100 million of venture capital in startups. Nationwide has already made investments in blooom, Nexar, Sure, Matic and Betterview, all of which focus on evolving the insurance and financial planning process.

Divorced Americans are at greater risk of not being able to maintain their standard of living in retirement, according to new research conducted by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College with the support of Prudential Financial.

The research study, which compares the risk divorced households face using the center’s National Retirement Risk Index (NRRI), reveals divorced households have a seven percentage-point greater risk of not having adequate retirement income than households that have not experienced divorce. Among all households, exactly half are at risk of not having adequate retirement income.

Annuities can offer a layer of protection because they can come with guaranteed income and other features to help generate income to supplement other retirement savings. And for people who are divorced or are contemplating divorce, annuities can be particularly important, particularly for the spouse with lower income.

The study’s findings show that on top of the normal retirement worries, divorced couples are dealing with legal fees, splitting assets and increased living expenses, and they must find ways of making up for that loss.

James Mahaney, a vice president in Prudential’s Strategic Initiatives unit, author of a companion paper to the NRRI study, recommended that people who are divorcing or contemplating divorce consider some key financial issues such as:

Alimony. Starting in 2019, alimony will no longer be tax-deductible for new divorces. This is likely to result in lower alimony being paid due to the higher taxes the combined former spouses must now pay.

Investments. After a divorce, individuals may find themselves in a lower tax bracket, which can be a benefit if they qualify for a zero-percent capital gains tax rate, making investing more affordable and rewarding.

Home ownership. Mothers of school-age children often prefer to keep the marital home when divorcing. Under the new tax law, however, home ownership in high-tax states may become less attractive.

Children and taxes. Although personal exemption deductions have been temporarily eliminated from the federal tax code, they have been replaced by child tax credits, which are more valuable than deductions. The credits reduce an individual’s tax burden on a dollar-for-dollar basis. Determining which parent can claim a child post-divorce may now be even more critical.

Social Security. Lower-earning spouses planning to divorce and who have been married for at least 10 years may be eligible for a Social Security spousal benefit or survivor benefit that could exceed their own benefit.

“Examining the Mindset of U.S. Financial Professionals,” a survey released this week by Schwab Independent Branch Services, finds that 76% of client-facing financial professionals have experienced obstacles that have limited their success, citing lack of support and limited autonomy.

Of the 994 survey participants, who have worked in the financial services industry for at least seven years and interact with investors once a week, 73% wish they could better assist clients and had more time to make an impact in the communities they serve.

Schwab Independent Branch Services launched in December 2011 to accelerate growth in new markets. Today there are 44 franchise offices in 24 states.

Those who participated in the survey say their profession is the most important thing to them (61%). Most (86%) feel successful; however, respondents did identify a number of obstacles that they’ve encountered in their careers:

The survey findings reveal some feelings of discontent and frustration; notably, 80% say they are ready to take their career to the next level, and 63% are ready for a change.

Milliman, Inc., the global consulting and actuarial firm, today released the results of its latest Pension Funding Index (PFI), which analyzes the 100 largest U.S. corporate pension plans.

In May, these pensions experienced a $2 billion dip in funded status as investment gains mostly offset a four-point decrease in the monthly discount rate. The funded ratio for the Milliman 100 PFI remains unchanged at 91.6% as of May 31.

“Sometimes no news is good news for corporate pensions,” said Zorast Wadia, co-author of the Milliman 100 PFI, in a release. “May’s 0.73% investment gain exceeded monthly expectations, and helped balance out the month’s modest decrease in corporate bond rates.”

From April 30, 2018 through May 31st, Milliman 100 PFI plans experienced a $7 billion increase in asset values, while the projected benefit obligations (PBO) rose by $9 billion. As a result, the deficit increased from $139 billion to $141 billion for the month. Over the last year (June 2017 – May 2018), the Milliman 100 PFI funded status deficit has improved by $116 billion.

Looking forward, under an optimistic forecast with rising interest rates (reaching 4.34% by the end of 2018 and 5.03% by the end of 2019) and asset gains (10.8% annual returns), the funded ratio would climb to 100% by the end of 2018 and 116% by the end of 2019.

Under a pessimistic forecast (3.64% discount rate at the end of 2018 and 3.03% by the end of 2019 and 2.8% annual returns), the funded ratio would decline to 87% by the end of 2018 and 81% by the end of 2019.

To view the complete Pension Funding Index, go to http://us.milliman.com/PFI. To see the 2018 Milliman Pension Funding Study, go to http://us.milliman.com/PFS/.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Still frustrated that the Boomer retirement wave hasn’t sparked a proportionate boom in income product sales, two dozen financial companies have started a not-for-profit organization to fund a multi-year, public-facing advertising and educational campaign to plead the case for annuities and other sources of retirement paychecks.

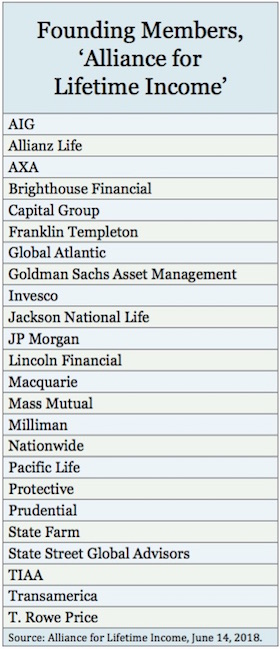

The 501(c)(6) organization is called the Alliance for Lifetime Income. Its founding members are life insurers or asset managers. After a competitive selection process, they engaged Statler Nagle—a Washington, D.C. communications firm whose only prior financial services client has been MasterCard.

Jean Statler

Alliance for Lifetime Income (it doesn’t use a three-letter acronym; ALI is taken) launches today. Its homepage, www.allianceforlifetimeincome.org, elevates today. Print ads, radio ads, twitter and other social media will complement the digital engagement strategy. National TV ads are planned for the fall, said Jean Statler, executive director of the organization and partner at Statler Nagle.

The organization was born out of conversations that started among members of the American Council on Life Insurers, according to an ACLI spokesman who said it has been working with the Alliance and supports its mission. Where the ACLI and the Insured Retirement Institute both lobby on behalf of the annuities industry, the Alliance will focus on messaging for individuals and advisors.

“The companies were looking at their own disparate efforts and realized that if they joined forces they could be more powerful together. We met with the IRI, and they have a more legislative mandate. The Alliance is focused on the consumer audience and advisors,” said Matt Conroy of Peppercomm, a public relations/marketing/communications firm based in New York that is working with the Alliance.

The organization’s list of founding members (see today’s Data Connection chart) includes the leading annuity issuers, a half dozen asset managers and some retirement plan providers, plus Milliman, the actuarial consulting firm. Currently absent are major players like BlackRock, Fidelity, New York Life and Vanguard. The Alliance did not indicate the amount of money provided by the founding members for the awareness campaign.

The campaign slogan is “Retire Your Risk,” Conroy said. “The companies will be simplifying the language around lifetime income products. People don’t understand these products very well.”

“It’s a new organization promoting protected monthly income,” said someone close to the Alliance’s founders who asked not to be identified. “It’ll be adding a strong voice to the debate on retirement security. They’ll emphasize education and simplification.”

“What’s new is that there are now 24 CEOs involved, from companies that are used to competing against each other in this space. That’s unprecedented,” a communications specialist from one of the founding members of the Alliance told RIJ.

As for the stubborn underlying question—why, given the Boomers’ needs, their professed appetite for safe income in retirement, and more than a decade of energetic messaging by the annuities industry, the industry hasn’t gotten more traction—Statler, an admitted newcomer to the world of annuities, isn’t sure what the answer is. She’s been told by the Alliance members that industry’s value proposition still isn’t understood very well by the public.

“In the research we’ve looked at and conducted, it all boils down to a misunderstanding about what [income] products offer,” Statler told RIJ. “We’ve looked at the IRI’s studies of their 150,000 advisors. We see a lack of understanding of the products or a sense that the products have to be shoehorned into [advisor] strategies. Advisors haven’t kept pace with the emerging products. And there’s so much momentum built up in rewarding advisors for wealth accumulation” [at the expense of distribution].

The organization will use a straightforward yardstick for success: greater market penetration of income products. Statler told RIJ this week, “The measurement that our eyes are fixed on is the number of ‘protected households.’ Today, about 48% of US households between the ages of 45 and 72 with between $75,000 and $1.99 million in investable assets are approaching retirement without protected monthly income other than Social Security.”

To measure the effectiveness of the campaign itself, she said, “Three times a year we’ll check to see if there’s more engagement, if people are going to the website. We’re not interested so much in hits or views as in whether people take our quizzes, or have called their financial advisors to ask about lifetime income.”

For life insurance industry expertise, the Alliance has engaged Colin Devine as its educational consultant and lead spokesperson. For 15 years until 2012, Devine was a life insurance company equity analyst and managing director at Smith Barney Citigroup, where he developed a reputation for candor and independence.

Colin Devine

“The annuity industry has dug a big hole for itself and people are turned off,” he said, adding that when individual annuity issuers have run ad campaigns, “people just zone out. What’s different about this is that it’s not just one company running ads. We want to educate people about a real risk that they face.”

“I have followed the [life insurance] companies for years,” Devine said, “and they relied largely on conducting feature wars, and to publishing illustration language that nobody understood. They created a situation where people didn’t understand the real issue, which is higher longevity. They relied on gimmicks and features rather than needs-based selling.

“It’s time we do a reset,” he added. “That means having the asset managers involved, and that we’re not talking only about one product, or one type of annuity, but a combination of products that can be used to generate stable income in retirement. You need a mix. That’s what’s different here.”

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

At the Morningstar Investor Conference in Chicago this week, Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman was asked to define an investor’s “best interest.” It was a timely question, given the recent failures of two federal agencies to create a clear or workable definition for brokers and advisors to follow.

Kahneman, whose pioneering work (with Amos Tversky) on risk perception and financial decision-making led to the 2002 Nobel in economics and to the influential book, Thinking Fast and Slow (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011), said that advisors can act in a client’s best interest by guiding them to their own unique “regret proof” strategy, “the kind of policy that people can live with even when things go badly.

Inside McCormick Place

“This is not necessarily profit-maximizing,” Kahneman told Morningstar’s Sarah Newcomb during their on-stage interview. “And the optimal allocation will not be the same for people who are prone to regret as for people who aren’t.”

One way to execute a regret-proof strategy in retirement, he said, is to divide a retiree’s money into a low-risk portfolio for essential needs and a higher risk portfolio for discretionary needs or just for the sake of upside potential. People tend to be satisfied if at least one of their buckets does well in any given market, he said.

During a Q&A session before more than 1,000 advisers and asset managers at Chicago’s vast McCormick Place, Kahneman also endorsed behavioral finance expert Meir Statman’s ideas about respecting a client’s emotionally driven preferences, even when they don’t seem fully rational to the adviser.

Taboo on spending principal

Retirement savings and distribution strategies didn’t receive a lot of attention at the conference, where most of the energy is devoted to mutual funds and accumulation strategies. But a couple of sessions, including one called “Show Me the Income,” touched on retirement-phase issues.

In that session, Wyatt Lee, co-portfolio manager of T. Rowe Price’s target date funds, talked about the benefits of payout mutual funds that would provide retired participants with a stable income based on distributions of earnings and principal without arousing their inborn resistance to spending principal.

“If you can repackage a total return strategy that meets people’s need for income, they will be drawn to it. Eating into principal isn’t a terrible strategy,” he said, adding that people already do it without knowing it. “People don’t want to sell some of their stock, even though selling shares for income is exactly the same as getting a dividend and using it for income. If you offer a fund that acts and feels like an income security, people won’t care if they’re getting a dividend or a gain.”

In a session called, “Evaluating the Government’s Approach to Helping Investors,” Morningstar’s Aron Szapiro, a former Government Accountability Office staffer, said that last December’s tax reform bill, by lowering to 21% the effective tax rate on business owner’s income, could eliminate a major incentive for small company owners to start retirement plans.

“The ‘pass-through provision effectively means that taxes will be higher not lower in retirement for business owners,” Szapiro pointed out. Therefore it doesn’t make much sense for them to save on a tax-deferred basis. In the past, the high deferral limit—currently $55,000 per year—has been a big selling point for advisers trying to sell 401(k) plans to small business owners.

Regarding regulations, Szapiro said that the SEC’s new Regulation Best Interest proposal is unprecedented in requiring broker-dealers to act in their clients’ best interests, and the requirement applies to rollover recommendations as well as sales.

But the SEC proposal doesn’t define “best interest.” “It’s not clear what the broker-dealers’ obligations will be,” Szapiro said. “We know that broker-dealers wouldn’t be operating under the same fiduciary standard as registered investment advisors [RIAs]. And there are no new rules for RIAs, just guidance. Where the DOL rule was product agnostic and specific to IRA accounts, the SEC proposal is account neutral but applies only to the products that the SEC regulates.”

Daniel Kahneman

Kahneman’s next book

During his interview with Morningstar’s Sarah Newcomb, Kahneman revealed that he’s currently working on a book with Cass Sunstein on the role of noise in decision-making. (Sunstein, who co-authored Nudge (Yale, 2008) with Nobelist Richard Thaler, is founder and director of Harvard’s Program on Behavioral Economics and Public Policy.)

“I’ve done a lot of work on biases and systematic errors. But there’s something even more important: unsystematic error or ‘noise’ as a random factor in the making of decisions,” Kahneman said. “We put a lot of weight on biases but not enough on the impact of noise.”

Kahneman said he once convinced an insurance company client to study their underwriters’ decisions. “We gave 50 underwriters the same case to work on, and we asked the executives, ‘How much do you think they will vary in putting a dollar value on the case?’ They predicted 10%.

“But when we took random pairs of those underwriters, and divided the differences between them by the average valuation, we got an average variation of 50%,” he said. “That was a lot more variability and noise than anybody was aware of. We found the same thing with claims adjusters. When there’s that much difference, even an unsophisticated algorithm might do better, because it’s noise-free. Our book will tell that story.”

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

News that the United States’ fertility rate fell in 2017 to 1.75 has provoked surprise and concern. A buoyant US economy in the 1990s and early 2000s was accompanied by fertility rates of 2.00-2.05 children per woman, up from 1.8-1.9 in the 1980s. But the increasingly strong economic recovery of the last five years has been accompanied by a declining birth rate. That seems to presage a long-term shortage of workers relative to retirees, and severe financial pressures on pension funds and health-care provision.

But the assumption that stronger growth and economic confidence must generate higher fertility—with low birth rates reflecting pessimism about the future—is not justified by the evidence. Moreover, fertility rates at around the current US level do not pose severe problems—and bring some benefits.

In all major developed economies, fertility rates fell during the 1960s and 70s, reaching levels below the replacement rate of around 2.05 children per woman. The US rate reached 1.77 in the late 1970s, compared to 1.8 in Northern Europe and 1.65 in Western Europe. And while we cannot be certain, the best expectation is that this shift to fertility rates significantly below the replacement rate will prove permanent, with temporary reversals driven by specific one-off factors.

Some viewed the US return to somewhat higher fertility rates in the 1990s as the consequence of greater economic dynamism and confidence, in contrast to “old Europe.” But throughout the last 30 years, fertility rates for white and black Americans have remained significantly below replacement level, and the three-decade rise and fall of US birth rates is explained primarily by higher Hispanic fertility, reflecting the common phenomenon that first-generation immigrants’ fertility rates are typically similar to those in their poorer countries of origin.

The same effect explains why Canada—with immigration skewed toward low-fertility Asian countries of origin—has had a significantly lower fertility rate of around 1.6. But with Latin American fertility rates now in steep decline—Mexico’s is down from 2.9 in 2000 to 2.1 today, and Brazil’s has fallen from 2.5 to 1.7—the immigrant-induced effect is disappearing, and the US is reverting to a typical fertility rate for a rich developed country.

Absent temporary migration-induced effects, all major developed economies have shifted to fertility rates of 1.2-2.0, with most falling between 1.3 and 1.9. And while there is some evidence that sudden deep recessions produce temporary fertility dips, followed by rebounds, cross-country comparison provides no evidence of any correlation—positive or negative—between medium-term economic success and precise fertility rates within this range.

Canada, with its lower fertility rate, is quite as successful and confident as the US. Strong German growth over the last 20 years has been combined with a fertility rate of 1.4-1.5, well below the 1.98 rate in less successful France. South Korea has maintained economic expansion with a fertility rate of just 1.2-1.3. Latin America’s most prosperous economy, Chile, has a fertility rate of 1.76, well below less successful Argentina’s rate of 2.27.

The recent decline in US fertility is therefore unsurprising; and, provided it does not fall to much lower levels, there is no cause for concern. Of course, in the long run, a lower fertility rate, combined with rising life expectancy, will produce a higher ratio of those over 65 years old to those conventionally labeled as “working age.”

But as people live longer and healthier lives, retirement ages can and should be increased. And in a world of radical automation potential, which threatens low wage growth and rising inequality, a rapidly growing workforce is neither necessary nor beneficial, and a slightly contracting supply of workers may create useful incentives to improve productivity and support real wage growth. Notably, fears that robots will take jobs are much less prevalent in Japan and China than in higher-fertility Western countries.

In rich developed societies with modern attitudes to the role of women, fertility rates somewhat below replacement levels may thus be both inevitable and broadly welcome. But degree matters, and extremely low fertility, such as Japan’s rate of 1.4, will create major problems if permanently maintained.

The United Nations median projection suggests that the total population of North and South America, after growing by another 15-20% between now and 2050, will remain roughly stable for the rest of the twenty-first century. By contrast, Japan’s population is projected to fall from 125 million today to around 80 million. Demographic contraction on that scale will severely stress Japan’s ability to support an aging population.

Intelligent policy should therefore identify and remove any barriers unnecessarily depressing birth rates, such as labor-market discrimination, limited parental leave, or inadequate childcare facilities, which make it difficult for women to combine careers with having as many children as they wish. The Scandinavian countries are exemplary in this respect, though fertility rates there have not returned to replacement levels, but only to about 1.75-1.9.

Similar policies in the US might marginally increase the fertility rate from today’s 1.75, with a mildly beneficial net effect. But the predominant response to America’s recent fertility decline should be to accept it as inevitable and to stop worrying about it.

Adair Turner, a former chairman of the United Kingdom’s Financial Services Authority and former member of the UK’s Financial Policy Committee, is Chairman of the Institute for New Economic Thinking. His latest book is Between Debt and the Devil.

Vanguard has announced that, effective June 25, 2018, it has pared down the list of investment options that it offers in its own employees’ 401(k) plan. Among those removed: Vanguard’s flagship S&P 500 Index fund.

A former Vanguard employee told the Philadelphia Inquirer, “The current problem with the Index 500 fund is over 25% of the fund is in technology stocks.” Vanguard views its Total Stock market index fund as offering participants better diversification and therefore less risk, he said.

The investments listed below will be removed from the Vanguard 401(k) retirement plan:

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

The Federal Reserve raised interest rates on Wednesday and signaled that two additional increases were on the way this year, the New York Times reported this morning. Officials said that the US economy was robust enough for the Fed to raise borrowing costs without blunting economic growth.

Wednesday’s rate increase was the second this year and the seventh since the end of the Great Recession and brings the Fed’s benchmark rate to a range of 1.75 to 2%. The last time the rate topped 2% was in late summer 2008, when the economy was contracting and the Fed was cutting rates toward zero.

Jerome H. Powell, the Fed chairman, said at a news conference that the economy had strengthened significantly since the 2008 financial crisis and was approaching a “normal” level that could allow the Fed to soon play less of a hands-on role in encouraging economic activity.

The rate increase could raise the costs of cars, home mortgages and credit cards over the next year, the report said. They could also mean higher returns on savings and higher payouts on annuities, although the impact of a rise in short-term rates but not in long-term rates—producing a flatter yield curve—is hard to predict.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Athene Annuity and Life Co., a unit of Athene Holding Ltd., has launched a new fixed indexed annuity (FIA) product, Athene Agility, for accumulation and income. The product includes income and death benefit riders at no additional charge.

Agility offers eight indexed crediting strategies, including market indices exclusive to Athene, and point-to-point interest crediting terms of one year and two years. The built-in income rider includes a deferral bonus and a participation feature in the income phase.

Before income begins, the income rider’s benefit base grows by 175% of any interest credits that are added to the annuity’s accumulated value. If during the accumulation period the account value went up 10% (to $110,000 from $100,000, for instance) then the benefit base would go up to $117,500.

In the income phase, Athene increases income by the percentage increase of the account value. “If I earn 4% in a year from index exposure, my income would go up in the following year by 4%,” an Athene spokesperson told RIJ. “If income had been $10,000 per year, it would increase to $10,400.”

Customers can start receiving income following a waiting period equal to the product’s surrender period.

Retirees will benefit from the adaptability of the product. In addition to the built-in income and death benefit features, customers can take free annual withdrawals during the surrender period up to 10% of the account value or initial premium.

On June 11, a subsidiary of Athene Holding Ltd. received notice of a regulatory matter from the California Department of Insurance regarding Accordia Life and Annuity Co., a subsidiary of Global Atlantic, and Athene.

The matter involves administration issues relating to certain California life insurance policies that were reinsured to Accordia and administered by a third party sub-contractor that was retained by Accordia, Alliance-One Services, an affiliate of DXC Technology, “Alliance-One”.

In 2013, in connection with the acquisition of Aviva USA, Athene reinsured a block of life insurance policies to Accordia. As previously described in our public disclosures, including our most recently filed Form 10-Q on May 4, 2018, the administration issues described above resulted from the conversion by Accordia and Alliance-One of these policies from legacy Aviva systems to Alliance-One systems.

Under the agreements, Accordia and its affiliates have financial responsibility for the block and are subject to significant administrative service requirements including compliance with applicable law. The agreements also provide for indemnification to Athene, including for administration issues.

The activity at issue does not involve Athene’s new business, which is administered under separate administration systems and procedures.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Private equity firms have sparked some activity in the otherwise quiet U.S. life/annuity mergers and acquisitions scene, according to a new A.M. Best report.

The Best’s Special Report, “Domestic Life/Annuity M&A Fueled by Non-Traditional Players,” says that L/A carriers see “valuations from heightened competition” to be the main stumbling block to them getting involved in M&A transactions.

But senior managers at a number of L/A carriers have told A.M. Best that the M&A pipeline is strong, and they have teams looking at a number of deals.

Small- to medium-sized carriers usually try to achieve growth by acquiring liabilities or distributions that can either enhance an existing profile or complement that business. Moreover, small players often lack the money and managerial expertise needed to keep pace with–let alone push ahead of–larger market players in the resource-intensive areas of enterprise risk management, innovation and cyber security.

Of the recent material private equity transactions, most involved the acquisition of variable annuity or fixed annuity businesses. These blocks generally line up well for private equity investors interested in managing the assets of run-off blocks of business. These run-off blocks also can become platforms for private equity firms to buy additional blocks to add to the run-off model and manage additional assets.

A.M. Best expects to see continued interest from private equity funds in the L/A segment. Transactions such as Talcott Resolution and Voya Financial (completed in May and June of 2018, respectively), have piqued buyers’ interest in other legacy variable annuity books of business.

Overall, A.M. Best believes private equity ownership remains a positive trend for the L/A industry. Although these ownership structures are somewhat less conservative on investments than traditional insurers, a rise in impairments for portfolios acquired and rebalanced has not been seen. In addition, product pricing for those firms with ongoing franchises has not been considered overly or more aggressive than for some non-private equity owned businesses.

Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith Inc. will pay more than $10.5 million back to its customers and about $5.2 million in federal penalties to settle charges that its employees led customers to overpay for Residential Mortgage Backed Securities (RMBS), the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) announced this week.

The SEC found that:

Merrill Lynch traders and salespersons deceived the bank’s customers about the price Merrill Lynch paid to acquire the securities and convinced them to overpay for RMBS.

Merrill Lynch’s RMBS traders and salespersons illegally profited from excessive, undisclosed commissions—“mark-ups”—some of which were more than twice the amount the customers should have paid.

Merrill Lynch failed to maintain compliance and surveillance procedures to prevent and detect this misconduct.

Merrill Lynch traders and salespersons violated antifraud provisions of the federal securities laws in purchasing and selling RMBS and that Merrill Lynch failed to reasonably supervise them.

Without admitting or denying the findings, Merrill Lynch agreed to be censured, pay a penalty of approximately $5.2 million, and pay disgorgement and interest of more than $10.5 million to the affected customers.

Melissa Lessenberry, Thomas Silverstein, and Kelly Rock conducted the SEC investigation, with help from Sharon Bryant, John Worland, and Sarah Concannon. Andrew Sporkin supervised the investigation, with assistance from the Special Inspector General for the Troubled Asset Relief Program and the Department of Justice.

MetLife and Brighthouse Life Insurance Company have agreed to work with the Department of Labor to determine whether more than 2,000 retirement plans in their custody are abandoned.

If the companies find that the plans are found abandoned, the companies will submit them to the DOL’s Abandoned Plan Program (APP). This may result in distributions of up to approximately $116 million to 20,000 participants. Ascensus Trust Company submits plans to the Abandoned Plan Program on behalf of MetLife and Brighthouse.

The companies also have agreed to terminate and wind up 400 additional “de minimis” plans, and to distribute the assets to their participants. De minimis benefits are those too small and infrequently provided to be worth tracking.

The DOL’s Employee Benefits Security Administration (EBSA) approached the two companies regarding the assets of Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA)-covered individual account plans that had no activity for at least 12 consecutive months.

A plan is considered abandoned if no contributions to or distributions from it have been made for 12 months. Such a plan may be appropriate for the AAP if the sponsor no longer exists, can’t be located with a reasonable effort, or can’t maintain the plan.

Asset custodians (like MetLife and Brighthouse) hold the assets of abandoned plans but can’t terminate them or to distribute their benefits to participants. In such scenarios, it’s hard for participants and beneficiaries to claim their money.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

Securian Financial is adding another fiduciary-friendly solution to its suite of products designed to expand access to employer-sponsored retirement plans in the small- to mid-sized business market.

MEPconnect is Securian Financial’s new open multiple employer plan. A MEP is a type of retirement vehicle maintained as a single plan while allowing multiple, unrelated employers to participate, achieving economies of scale typically only attained by larger plans.

MEPs operate similar to traditional single employer retirement programs but with the majority of the administrative and fiduciary duties outsourced to retirement professionals—minimizing the adopting employer’s involvement while maximizing fiduciary protection.

“As much as they’d like to offer it as a benefit to their employees, many small business owners know that sponsoring a retirement plan can take specialized knowledge and add time-consuming administrative and fiduciary obligations to their already busy workload,” said Rick Ayers, Securian Financial’s vice president of retirement solutions.

“MEPconnect incorporates the key features of an effective plan while transferring the bulk of the work and risk to third-party retirement professionals—making it easy for employers to stay focused on running their businesses.”

Securian Financial provides complete recordkeeping services and a robust investment platform for MEPconnect, along with easy access to account tools and resources through a secure website. Securian Financial teamed up with two other industry professionals to complete the streamlined retirement plan for employers:

The Platinum 401(k) assumes the role of the ERISA 3(16) Plan Administrator and principal fiduciary for administrative functions of the plan.

Fidelis Fiduciary Management serves as the ERISA 3(38) Investment Manager, taking full fiduciary responsibility and discretion regarding the selection and monitoring of investments offered under the plan.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC.

The United States has an enormous and rapidly widening budget deficit. Under existing law, the federal government must borrow $800 billion this year, and that amount will double, to $1.6 trillion, in 2028. During this period, the deficit as a share of GDP will increase from 4% to 5.1%. As a result of these annual deficits, the federal government’s debt will rise from $16 trillion now to $28 trillion in 2028.

The federal government’s debt has risen from less than 40% of GDP a decade ago to 78% now, and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) predicts that the ratio will rise to 96% in 2028. Because foreign investors hold the majority of US government debt, this projection implies that they will absorb more than $6 trillion in US bonds during the next ten years. Long-term interest rates on US debt will have to rise substantially to induce domestic and foreign investors alike to hold this very large increase.

Why is this happening? Had last year’s tax legislation not been enacted, the 2028 debt ratio would still reach 93% of GDP, according to the CBO. So the cause of the exploding debt lies elsewhere.

The primary drivers of the deficit increase over the next decade are the higher cost of benefits for middle-class older individuals. More specifically, spending on Social Security retirement benefits is predicted to rise from 4.9% of GDP to 6%. Government spending on health care for the aged in the Medicare program – which, like Social Security, is not means tested – will rise from 3.5% of GDP to 5.1%. So these two programs will raise the annual deficit by 2.7% of GDP.

This officially projected increase in the annual deficit would be even worse but for the fact that the cuts in personal income tax enacted last year will lapse after 2025, reducing the 2028 deficit by 1% of GDP. The official deficit projections also assume that the recently enacted increases in spending on defense and non-defense discretionary programs will be just a temporary boost. Defense spending is expected to decline from 3.1% of GDP now to 2.6% in 2028, while the GDP share of non-

defense discretionary spending will fall from 3.3% to 2.8%. These deficit-shrinking changes are unlikely to happen, causing the 2028 deficit to be 7.1% of GDP – two percentage points higher than the official projection.

If a deficit amounting to 7.1% of GDP were allowed to occur in 2028, and to continue thereafter, the debt-to-GDP ratio would reach more than 150%, putting the US debt burden in the same league as that of Italy, Greece, and Portugal. In that case, US bonds would no longer look like a safe asset, and investors would demand a risk premium. The interest rate on government debt would therefore rise substantially, further increasing the annual deficits.

Because financial markets look ahead, they are already raising the real (inflation- adjusted) interest rate on long-term US bonds. The real rate on the ten-year US Treasury bond (based on the Treasury’s inflation-protected bonds) has gone from zero in 2016 to 0.4% a year ago to 0.8% now. With annual inflation running at about 2%, the increase in the real interest rate has pushed the nominal yield on ten-year bonds to 3%. Looking ahead, the combination of the rising debt ratio, higher short- term interest rates, and further increases in inflation will push the nominal yield on ten-year bonds above 4%.

What can be done to reduce the federal government’s deficits and stem the growth of the debt ratio? It is clear from the forces that are widening the deficit that slowing the growth of Social Security and Medicare must be part of the solution. Their combined projected addition of 2.7% of GDP to the annual deficit over the next decade is more than twice the officially projected rise in the ratio of the annual deficit to GDP.

The best way to slow the cost of Social Security is to raise the age threshold for receiving full benefits. Back in 1983, Congress agreed on a bipartisan basis that this threshold should be raised gradually from 65 years to 67, cutting the long-run cost of Social Security by about 1.2% of GDP. Since 1983, average life expectancy of individuals in their mid-sixties has increased by about three years. Raising the future age for full benefits from 67 to 70 would cut the long-run cost of Social Security by about 2% of GDP.

At this time, slowing the growth of Social Security and Medicare is not a politically viable option. But as the deficit increases and interest rates rise, the public and the Congress might return to this well-tried approach.

My sympathies go out to the writers at the SEC.

The Securities & Exchange Commission did not define “best interest” in its Regulatory Best Interest proposal. Why? A true definition isn’t an option for it or the financial industry… or even for most clients.

A client’s interest is best served when he/she pays a self-employed expert–be it an advisor, doctor or plumber–whose own interest is to win the client’s trust and act as his/her loyal guide. Best interest is no more ambiguous than the Hippocratic Oath or the Golden Rule.

But a straightforward definition is unworkable as a standard for real-world behavior; it is incompatible with the industry’s structure. First, self-employed advisors are relatively scarce, given the flood of investors created by the 401k system.

Second, the third-party product distribution model appears to be independent but creates invisible ties between advisors and manufacturers. (Hence the inevitable, unmanageable conflicts.)

Third, clients themselves are complicit; they’re reluctant to write personal checks for bespoke advice. So a true definition of best interest can’t be written. It must be fudged.

After I expressed these opinions on LinkedIn last week, Stephen Mitchell, a managing consultant at BrightPoint asked, “Why do you make the distinction ‘self-employed’ expert? Does this suggest that a firm of any type can’t act in the client’s best interest? How the firm makes money may make it more or less difficult, but I’m not sure it’s that different that for a self-employed advisor… and a large firm collectively has more expertise.”

The point isn’t that an employee-advisor will never steer me right, or that a self-employed advisor will never steer me wrong. Reality is a mixed bag. The point isn’t that only self-employed advisors should advise. That’s not practical. (To me, “self-employed” implies that the client alone pays the advisor; but a transparent “A” share commission might suffice.” )

But I don’t think a claim to acting in a client’s “best interest,” if that term is going to be a legal standard and not a loophole, can or should be made by someone trying to serve more than one master. As for expertise, a large firm can have lots of it, but I can’t be sure that it will be used to my advantage.

James Watson III, an attorney, CFP and CEO at InvestSense LLC, commented, “The SEC speaks of harmonization between it and the Department of Labor. If that is its true goal, then the easiest solution would be for the SEC to adopt the ‘best interest’ definition from the DOL’s rule.” That may be true, but the brokers won’t stand for it.

The core issue isn’t hard to describe. Tax-deferred rollover IRAs fall into a regulatory grey zone where the pension and the brokerage worlds overlap. While it’s not quite right to apply pension fiduciary standards to brokerage accounts, it’s also not quite right to apply brokerage suitability standards to pension accounts.

Given the stakes involved—access to $9 trillion in IRAs—sheer political power can be expected to decide the outcome. With the 2016 election, “ball possession” changed from the pension-oriented DOL to the brokerage-oriented SEC. Unlike the DOL, the SEC doesn’t need to score to win this game. It can afford to punt.

© 2018 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.