Ten years ago, sales of fixed indexed annuities (FIAs) were largely confined to the life/annuity industry’s ‘Wild West’ territory. Since then, the FIA has gained respectability and emerged as one of the industry’s flagship products. In this article, we’ll review and reflect on some of the changes that have occurred in this product category from 2011 to 2021.

A lot has changed in the FIA space over the past 10 years. A lot has stayed the same.

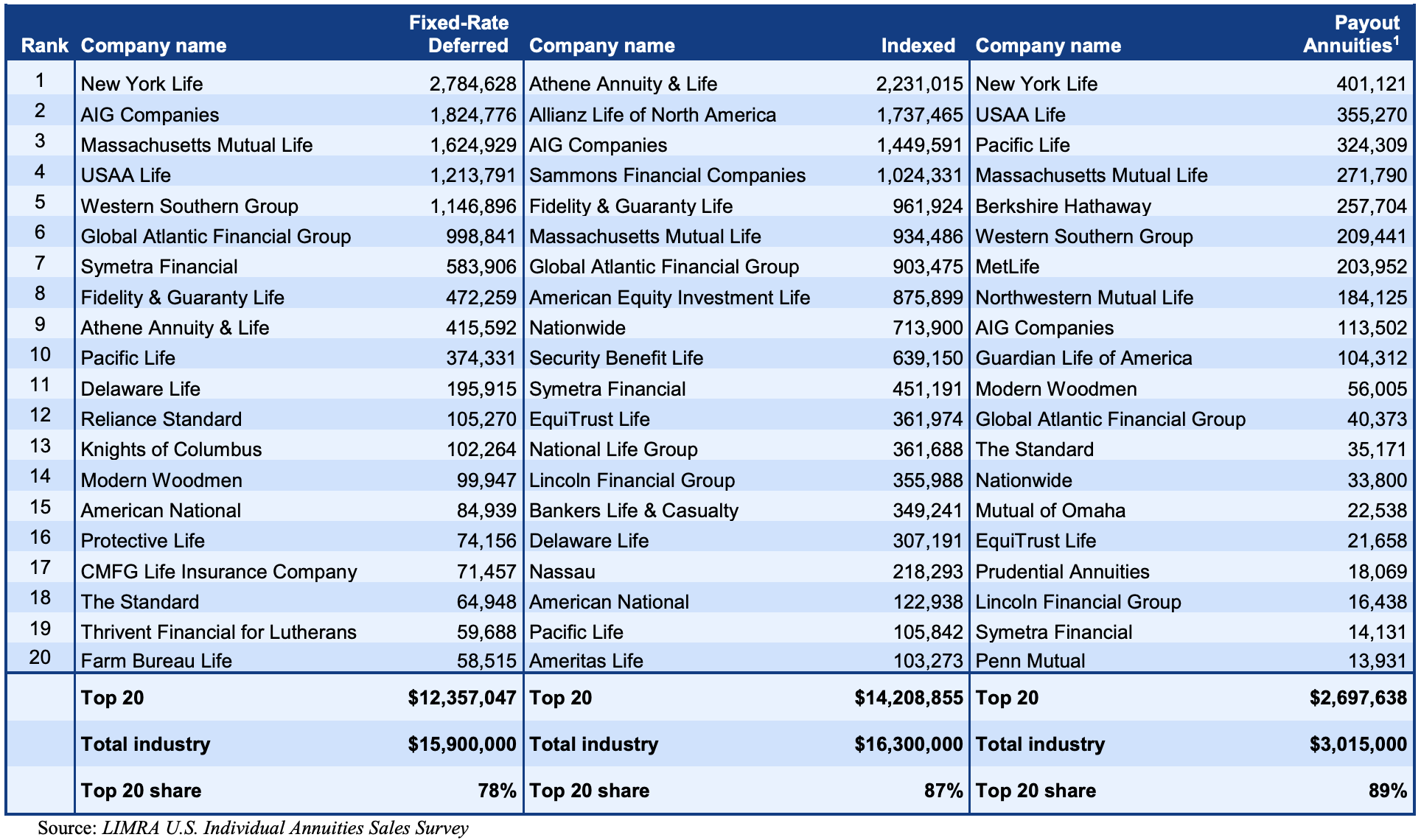

Many of the same life/annuity companies that dominated FIA sales 10 years ago dominate it today. Athene USA and Allianz Life are perennial leaders. But big private equity firms, also known as “alternative asset” managers, have revolutionized the way that leading FIA issuers manage their policyholders’ money.

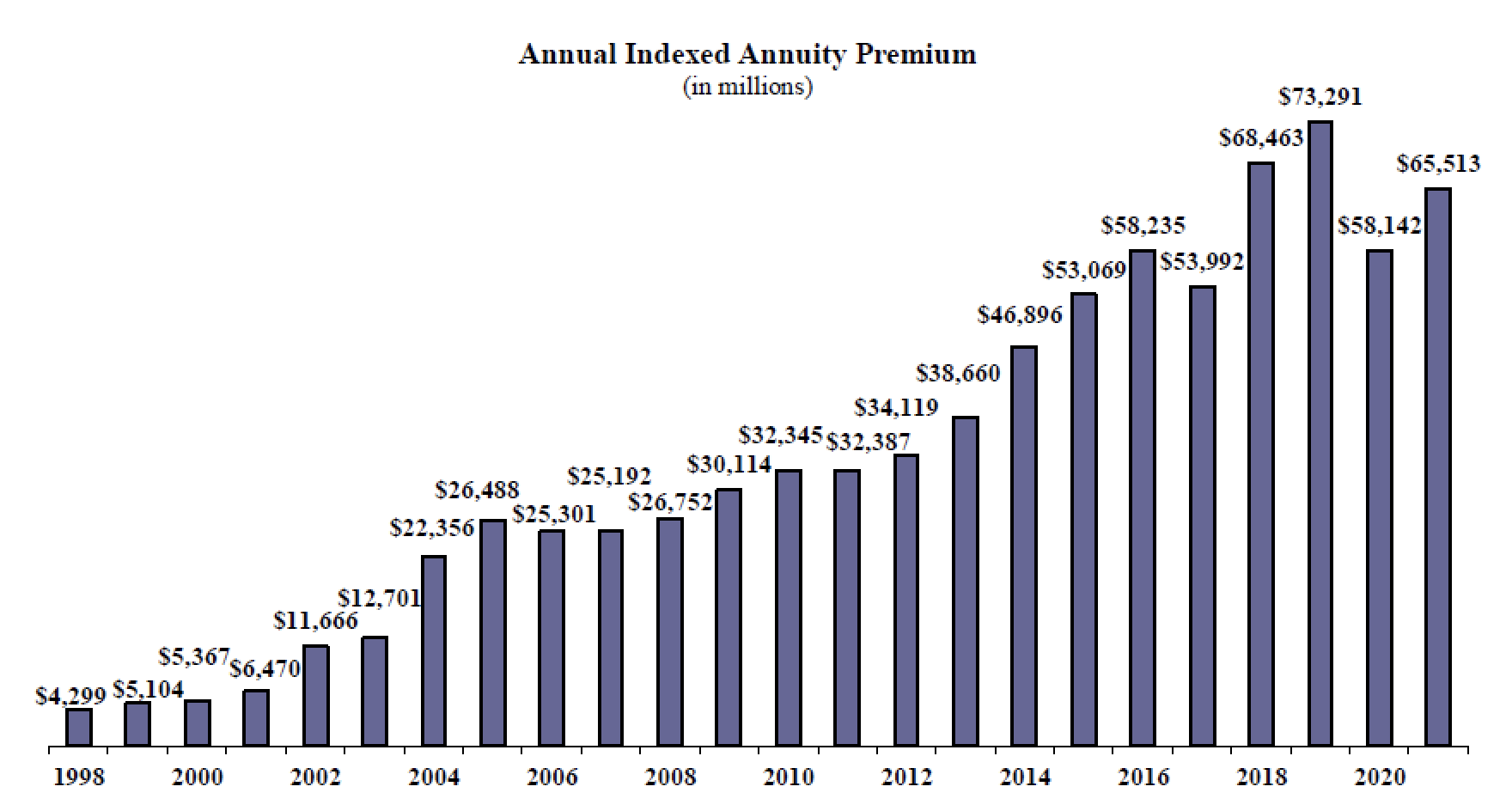

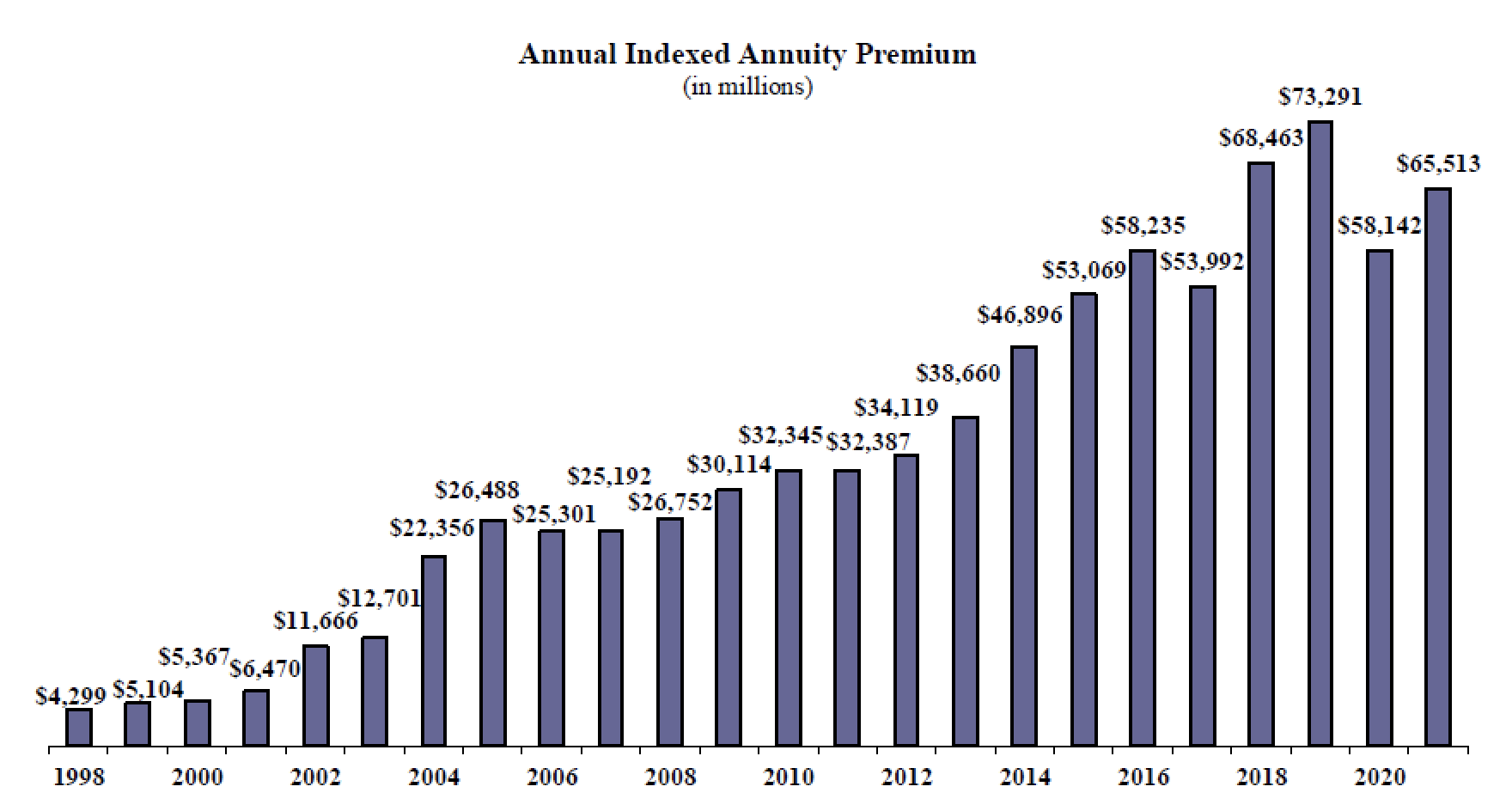

FIA sales have doubled over the past 10 years, to about $65.5 billion in 2021, according to Wink’s annual survey of issuers. Sales are diversified across more distribution channels. FIAs outsell fixed-rate annuities, registered index-linked annuities (RILAs), and income annuities. They are on track to outsell traditional variable annuities, whose sales have been in decline.

The rise of FIAs has coincided with a period of historically low interest rates and rising demand for safe investments among aging Baby Boomers. Through the purchase of options on equity (and now “hybrid”) indexes, FIAs offer a chance for higher returns than bonds or certificates of deposits along with a guarantee against market-related losses. Their success is a sign of the times.

Every June, RIJ and Wink, Inc., collaborate to analyze a slice of Wink’s proprietary data on annuity sales and distribution in the prior year. Last year, we reviewed RILAs. This year we return to FIAs because they’re a vital component of the life/annuity industry’s “Bermuda Triangle” business strategy (as we’ll explain below).

The leading FIA issuers

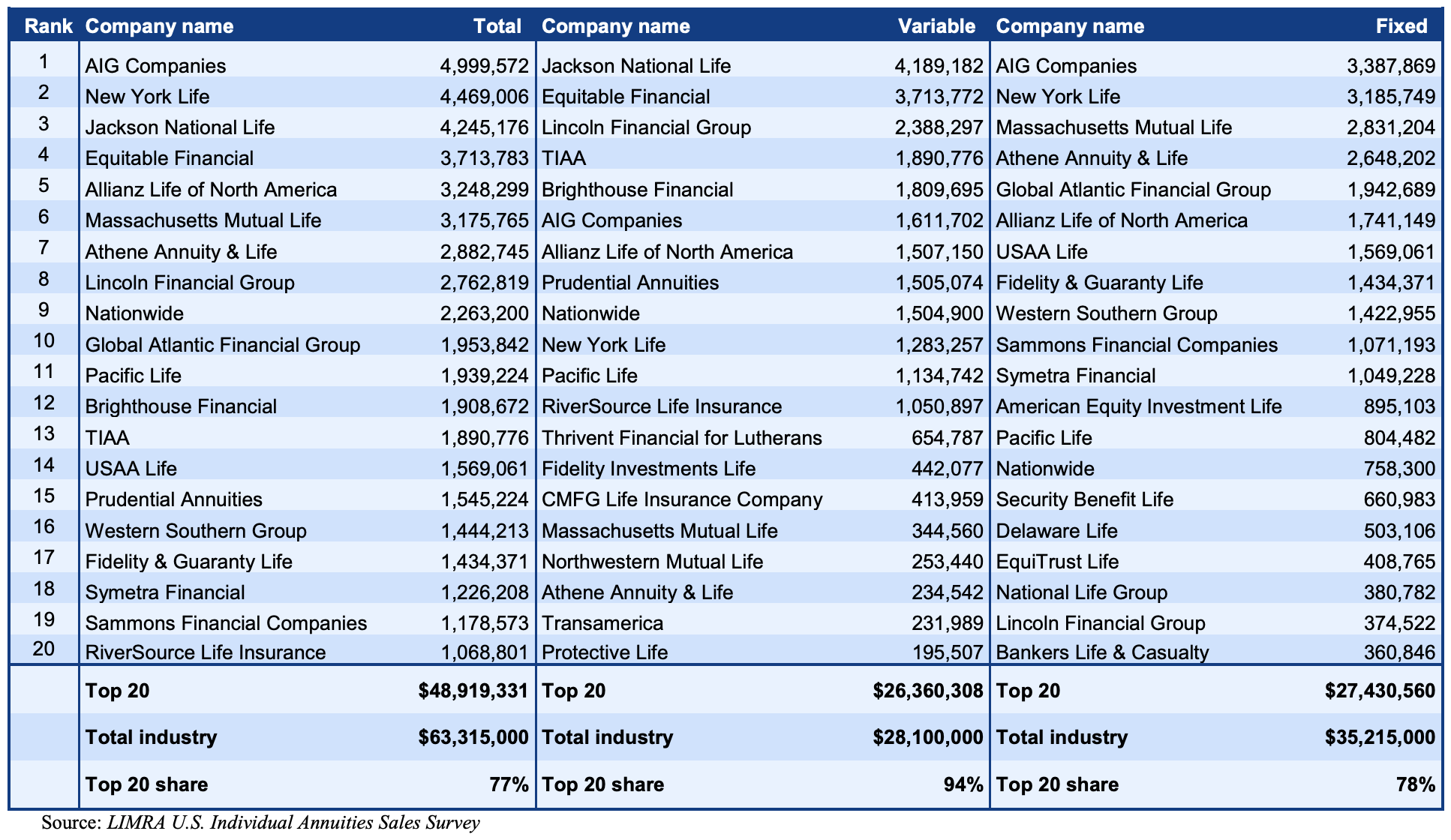

In terms of FIA sales, the strong have gotten stronger. For the 12th time in the last 18 years, Athene USA, which is part of Apollo Global Management, and Allianz Life, the US subsidiary of Allianz of Germany, finished first or second in the FIA sales race. Reviewing the list of the 10 best sellers of FIAs for 2021, Moore said the list has been notably stable since 2011.

“You’re seeing many of the same names at the top of the leaderboard. Jackson National and Lincoln National are no longer there,” she told RIJ. “But there are others—Athene, Allianz Life, American Equity—who have always appeared in the top 10 in sales.”

Sammons is a newcomer in name only; it is the parent company of two perennially strong FIA issuers—Midland National and North American. Great American wasn’t on the leaderboard in 2021 only because it was purchased by MassMutual. If you added the FIA sales of MassMutual and Great American together in 2021, their $3.7 billion in sales would put them in sixth place, just ahead of American Equity.

The biggest life/annuity company to break into the top 10 FIA issuers since 2011 has been AIG. (AIG plans to spin off its retirement division in an IPO this year; Corebridge, as it will be called, may be on this list.) The largest FIA issuer to bow out since 2011 has been Jackson National Life. Fidelity & Guaranty Life and Security Benefit Life fell from the top 10 in 2016, but they dropped only to 11th and 12th place, respectively.

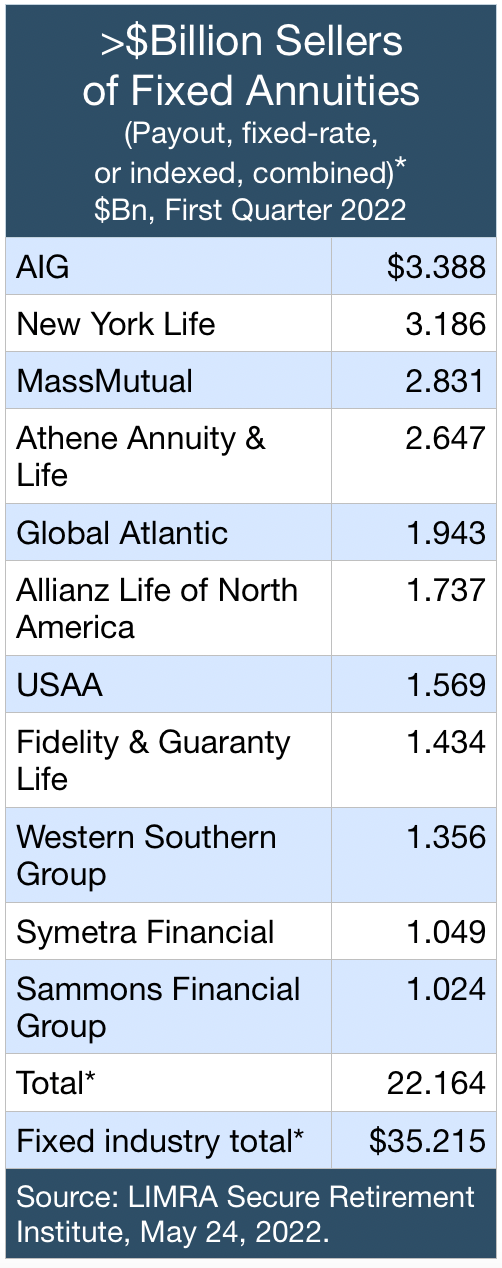

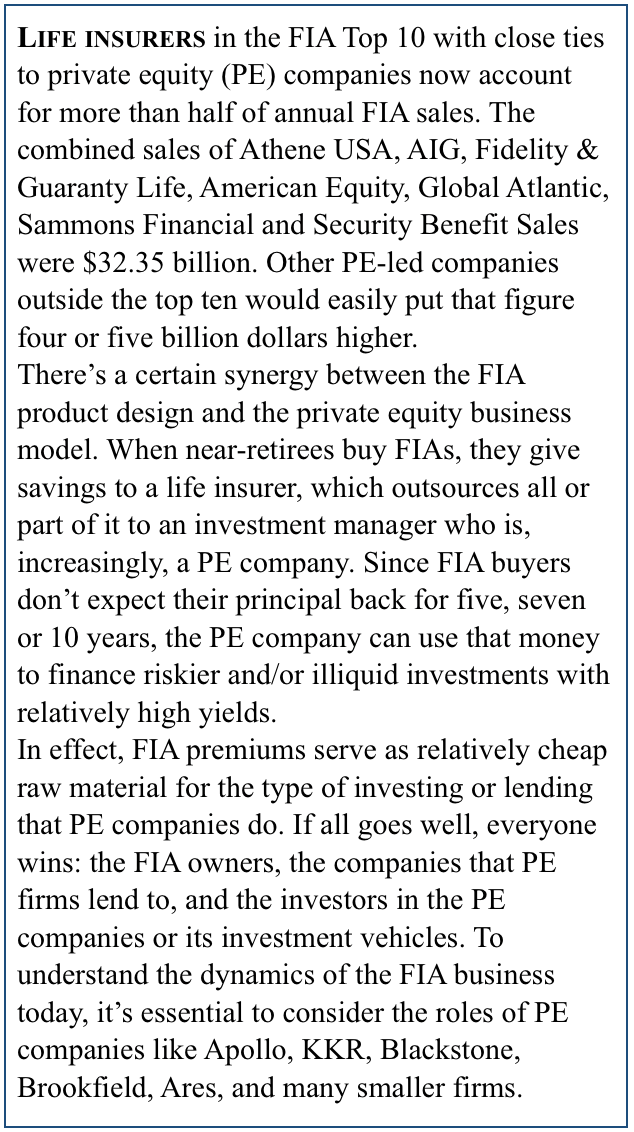

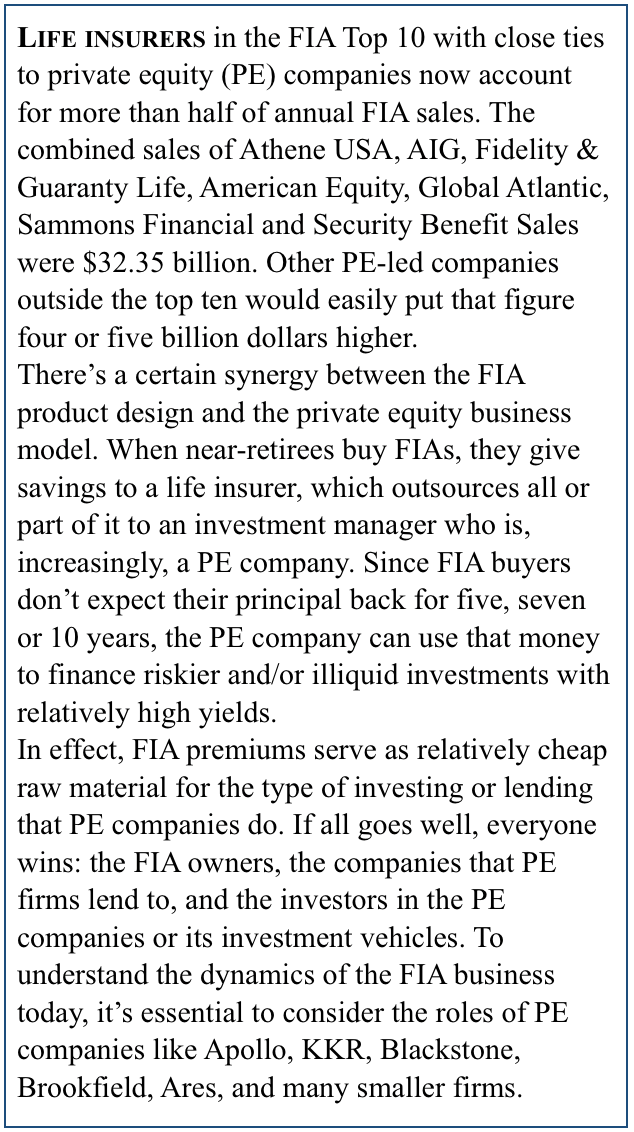

Private-equity companies have more become involved in the FIA business over the past decade. That’s not readily apparent from a quick glance at the names on the top-10 list. But as many as seven of the 10 leading sellers of FIAs now have ownership ties or strategic partnerships with large private equity companies.

Athene USA, for instance, is a product of Apollo Global Management’s 2012 purchase of Aviva. Sammons owns part of Guggenheim Partners. Eldridge Industries, a holding company run by former Guggenheim Partners executive Todd Boehly, owns Security Benefit Life. Blackstone owns almost 10% of AIG’s retirement business (of which FIA sales are a part), and manages Fidelity & Guaranty Life’s investments. American Equity has been remaking itself into an investment-oriented company with the help of private equity firms. Global Atlantic is owned by KKR, the giant alt-investment firm.

Are these FIA issuers successful because they have the backing of private equity firms, or have private equity companies merely snagged the best FIA issuers? Moore gives more credit to the latter part of that question.

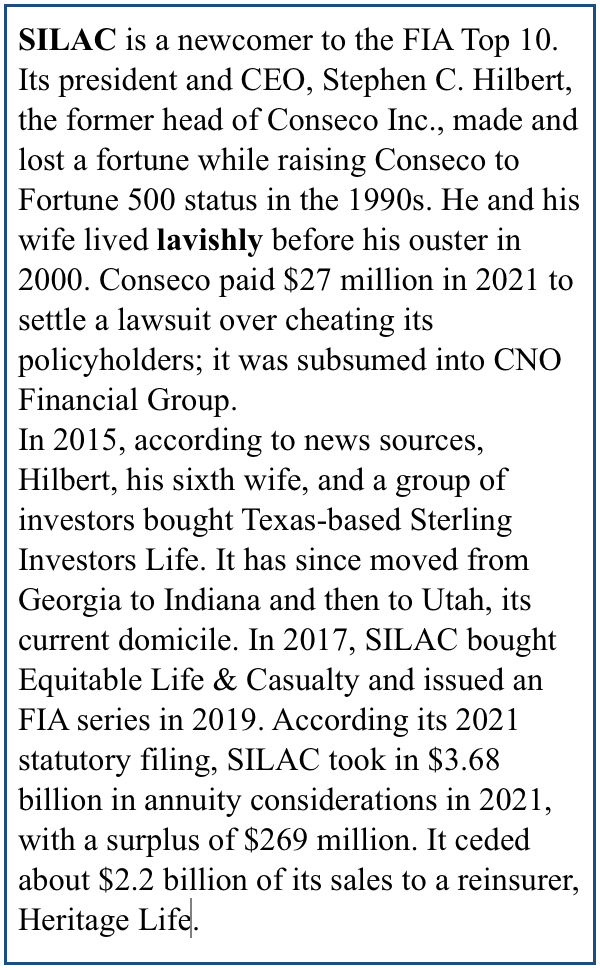

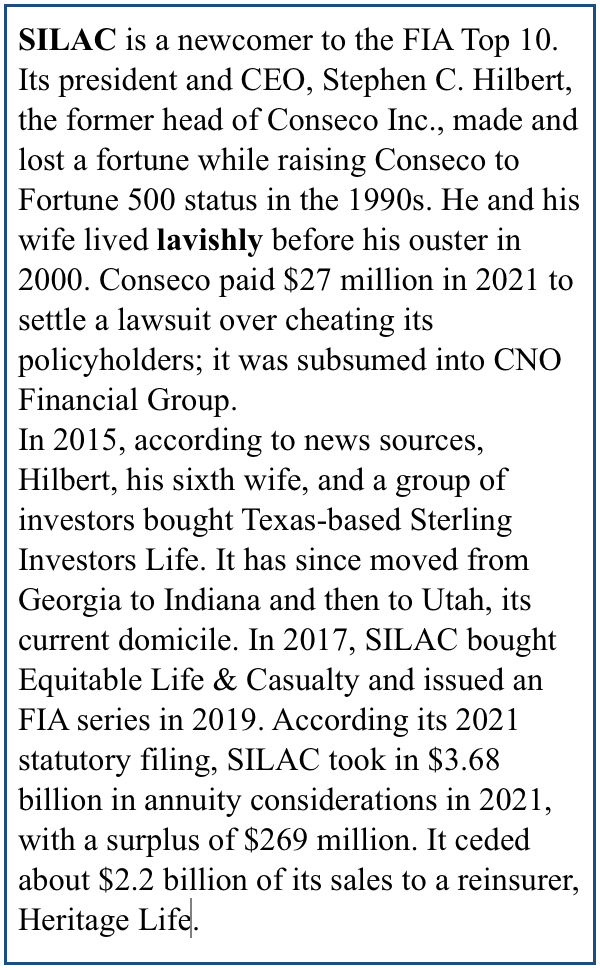

Sheryl Moore

“The companies that have been acquired by the private equity firms were already successful prior to being acquired. Their product competitiveness may have increased after they were purchased, but not to the point where you’d say, ‘Whoa. What happened here?’ They’re distinct from the start-ups, like SILAC, whose strategy is to capture fixed-rate annuity sales with a competitive rate, and then transition to an indexed product. SILAC is now in the top 10.”

Sales volume doubled in 10 years

Like financial camels in a desert of yield, FIAs have shown themselves to be well-adapted to the low interest rates environment of the past 14 years. Sales rose from $32.387 billion in 2011 to $58.235 billion in 2016, to $65.513 in 2021. That was off the peak year of 2019 but up from 2020, when sales dropped to $58.142 billion amid the COVID epidemic.

“What impresses me is that the average premium has consistently gone up regardless of how sales are fluctuating,” she said. For the companies participating in her survey, the average indexed annuity premium in the fourth quarter of 2011 was $66,758, with a range of $1,700 to $142,966 and 92,703 contracts sold in the quarter. In 2016, the average premium was $105,264, with a range of $15,233 to $180,250 and 126,373 contracts sold in the fourth quarter. In 2021, the average premium was $147,860, with a range of $21,923 to $291,154, with 109,863 contracts sold in the quarter. “People are not only buying more indexed annuities, they’re also putting more of their assets into them. The low interest rate environment has fueled that trend.”

“Although the ownership and management of the company may be different, the same people are working there, and doing the same jobs. Some private equity firms have just let the companies they acquire run as usual. Others, like Athene, Sammons, and Fidelity & Guaranty, have been aggressive in increasing sales. American Equity, which was normally near the top in sales, has been down a little,” Moore said. All four of those companies now leverage the expertise of firms with private equity and private credit expertise.

“Although the ownership and management of the company may be different, the same people are working there, and doing the same jobs. Some private equity firms have just let the companies they acquire run as usual. Others, like Athene, Sammons, and Fidelity & Guaranty, have been aggressive in increasing sales. American Equity, which was normally near the top in sales, has been down a little,” Moore said. All four of those companies now leverage the expertise of firms with private equity and private credit expertise.

For all annuity issuers, an inherent tension exists between sales volume and financial strength, Moore pointed out. “The companies ask themselves, ‘How badly do we want the new annuity sales and how much do we want to sacrifice strength?’” she added. Sales and financial strength are related, Moore said. To maintain a certain strength rating, a company might have to add capital when it takes on more annuity liability—in the form of new premium. “Each company sets a target for the amount of annuities it wants to sell and keep the same ratings. If they exceed that amount, it could hurt their ratings.”

The ‘Bermuda Triangle’ factor

After buying Aviva in 2012 and turning it into Athene, Apollo pioneered what RIJ has called the Bermuda Triangle model. Much copied since then, the strategy typically involves the coordinated activity of an FIA issuer, an asset manager skilled in originating high-risk “leveraged loans” and other alternative assets, and a Bermuda or Cayman Islands reinsurer. We focus on the reinsurance angle here.

Athene USA, for instance, used reinsurance in 2021 to move billions of new FIA sales off of its balance sheet and onto the balance sheets of reinsurers within its own holding company.

On its annual statutory filing in Iowa, Athene Life and Annuity of Iowa reported about $22.4 billion in new annuity sales in 2021. Of that amount, Athene “ceded” about $18.8 billion to Athene Annuity Re of Bermuda and to an Athene affiliate in Delaware.

Source: Wink, Inc.

Athene USA reported $7.7 billion in indexed annuity sales to Wink, Inc., but only $775 million in indexed annuity sales on its statutory filing. (About $10 billion of Athene’s $22 billion in annuity sales involved group annuities, or pension risk transfer deals.)

Moore believes that reinsurance raises sales capacity for life/annuity companies, but she has no data on how it might do so. In any case, the same asset manager—Apollo—added $22.4 billion to its assets under management because it does the investment chores for Athene Life and Annuity, Athene Annuity Re, and Athene Delaware.

The rise of hybrid indexes

When you buy an FIA, the issuer puts your money in its general account for long-term investment (mainly in bonds). Then it takes the equivalent of about 3% of your investment (that’s about what your premium was expected to earn in the general account, minus fees and overhead) and buys a bracket of options on a market index. Typically, if the index rose during the next 12 months, you’d lock in a piece of that gain. If the index dropped, you’d get nothing and lose nothing—except the 3% that a comparable non-index-linked, fixed rate annuity would have paid you. [The term length of the contract may be five to 10 years, but credits are typically locked in each year.]

Most FIA contract owners used to bet routinely on the movement of the S&P 500 Price Index. (That’s the S&P 500 Index, minus the dividend yield. Options on the pure S&P 500 Index would be more expensive.) In 2011, about 62% of all FIA premium was pegged to the S&P 500 Price Index. (Another 22% went into a fixed return account.) In 2016, about 47% of FIA premium went into the S&P 500 Price Index; 30% went into new, sophisticated, volatility-controlled hybrid or “custom” indexes.

Today, only about one-third of FIA premium is pegged via options to the S&P 500 Price Index. Almost 60% goes into hybrids, of which there are dozens. “When I started in this business, there were 12 indexes,” Moore said. “The last time I counted, there were 150. Sometimes I have to wonder if we are complicating the indexed annuity story with so many ways of earning indexed interest.”

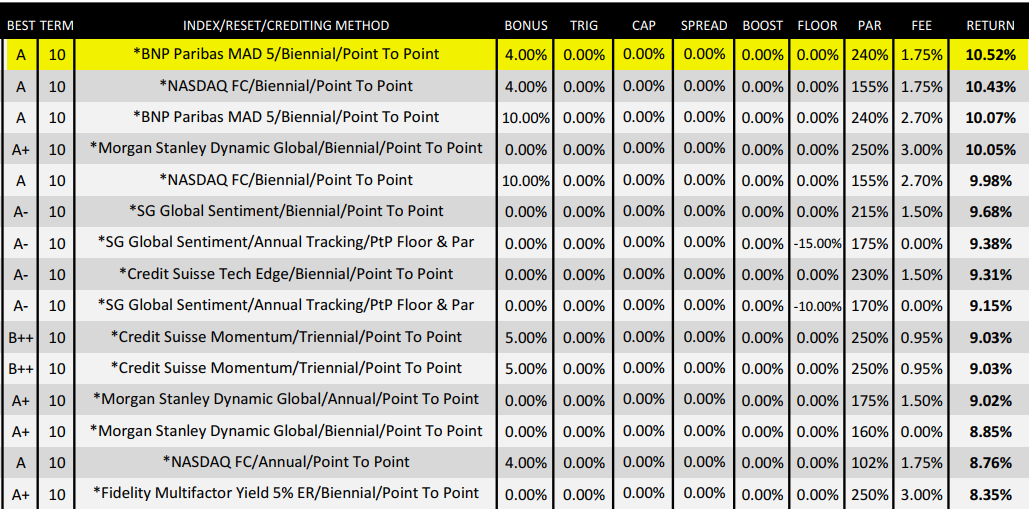

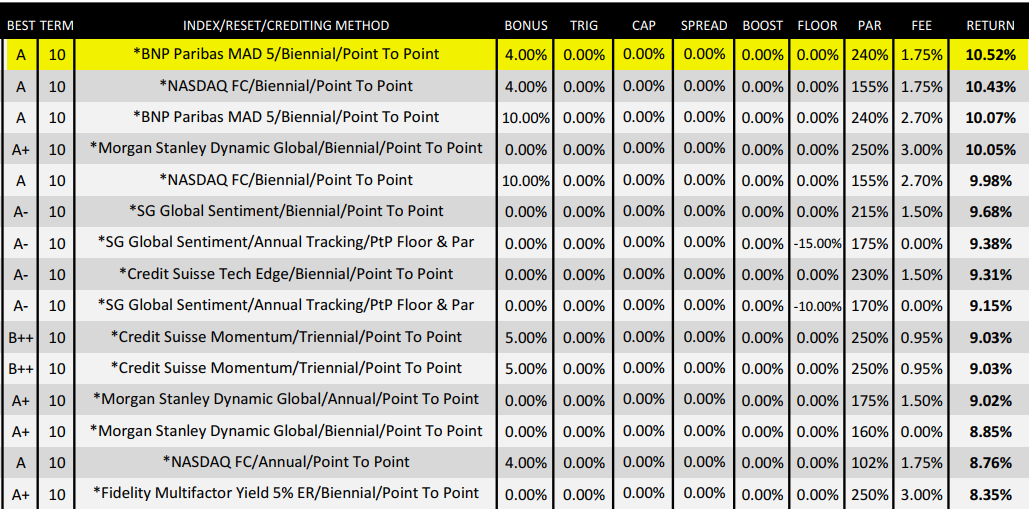

Source: Safe Harbor Financial.

Most FIA contracts now offer one or more hybrids, in addition to more familiar ones. They are called hybrids because they may contain several different asset classes. They are called custom because investment banks like Morgan Stanley, Credit Suisse, and BNP Paribas have created them specifically for FIA issuers.

The use of hybrid indexes has paralleled the growth in FIA sales over the past decades. That may not be a coincidence. Since the algorithm-driven hybrids often target a particular volatility rate, such as 5%, their up or down movements are inherently limited. Because the controls are internal and unseen, the issuers don’t need to declare strict external performance limits, such as single-digit caps or sub-100% participation rates.

FIAs without caps or with participation rates in excess of 100% are particularly attractive to investors, because gains appear unlimited. As you can see by the list of top-performing hybrid indexes recently released by Safe Harbor Financial, an index annuity wholesaler, none of the indexes feature a cap and all of them have participation rates over 100%. “That’s a big sales incentive,” Moore said.

Many of the hybrids are less than a few years old, and every hybrid in this chart require a commitment of 10 years. Unlike the S&P 500 Price Index, the hybrids have little or no track record. This doesn’t prevent promoters from “back-testing” hybrids against market history to arrive at flattering performance histories. The hybrids on the chart show average historical returns as high as 10.52% per year over the past 10 years. That’s a powerful lure, especially when coupled with a no-loss guarantee.

Historically, FIA marketers have advertised the product’s zero explicit fees and zero risk of loss. But some FIAs now feature annual fees. There are fees for riders that allow the contract owner to draw a guaranteed minimum lifetime income stream from the product. There are also fees that amplify the product’s option budget and allow the issuer to offer participation rates in excess of 100% of the index return. Over 10 years, those fees could produce a net loss of principal for the investors. “The old battle cry of ‘Zero is your hero!’ is no longer valid if clients are paying explicit fees,” Moore told RIJ.

Commissions

Independent insurance agents can earn higher commissions from selling FIAs than they can from selling any other kind of insurance product. High commissions and other incentives, financed by the life/annuity companies (and recouped by them over the life of the product), jump-started the FIA business in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Before the Great Financial Crisis, the average FIA commission exceeded 8% and commissions of 9% to 11% were not unusual. After the crisis struck, the average dropped. “The top-selling annuity pays a 6.5% street-level commission, which is the maximum that [wholesalers, such as field marketing organizations or FMOs] can advertise. The street-level rate doesn’t include the ‘override’ that the wholesalers receive, which can be as high 3%. The average all-in distribution cost is about 8% to 9%,” Moore said.

Surrender periods

Commissions are higher when surrender periods are longer. (During the surrender period, the contract owner pays a penalty for withdrawing an amount that ranges from 5% to 15%, depending on the contract.) Over the past 10 years, the percentage of contracts sold with a 10-year surrender period has held steady at about 50%.

In 2011, only 15% of contracts had surrender periods that were seven years or less. That figure rose to 25% in 2016 an 36% in 2021. “The decline in commissions is tied to the rising popularity of shorter surrender periods,” Moore said.

“We are seeing more five-year and seven-year products in the independent agent channel. There are a lot of agents who say, ‘I won’t put my clients in a 10-year product today when interest rates are likely to go up in a few years.”

Distribution channels

Surrender periods tend to be shorter on contracts sold in the bank and broker-dealer channels. “Sales of five-year and seven-year have increased as we’ve seen more companies serving the bank and broker-dealer channel enter the market. The compliance departments of those banks won’t allow longer-term surrender periods,” Moore said.

Ten years ago, in the twilight of what had been known as the “Wild West” era of the FIA business, almost 90% of FIAs were sold by independent insurance agents. By 2016, other distributors, especially independent broker-dealers and banks, began carrying the product as a high-yield alternative to bonds.

Insurance-licensed advisers at independent broker-dealers and at banks each accounted for about 14% of sales in 2016, as the insurance agent channel share fell to 61%. In 2021, sales in the independent broker-dealer channel had dropped to 10.8% and the independent agent share bounced up to 65%. Athene was the biggest seller in that channel last year.

Income riders

FIA issuers have been adding “guaranteed lifetime withdrawal benefit” riders (GLWBs) to their contracts for several years. These riders typically require an explicit fee of 1% or more, and they often require a 10-year holding period in order to achieve their maximum value to the contract owner. Contracts can dip into their principal even after starting income, but their income may drop if they do.

About half of the FIA contracts sold in 2021 had lifetime income riders, Moore said. In 2016, according to her data, among carriers in her survey that offer lifetime income riders on their FIAs, an average of 20.4% of the contract owners were drawing income. It’s difficult to say how many might plan to use them in the future. Very few, if any, owners of FIA contracts “annuitize” them—that is, convert them irrevocably to an income stream for the life of the owner.

Conclusion

Over the past 10 years, a lot has remained the same in the FIA business. People of the same age range—55 to 65—are buying them. Products with the highest crediting rate still attract the most interest from investors. When interest rates are low, FIAs can be expected out-yield certificates of deposits and bonds. Independent insurance agents still sell a majority of the contracts.

But a lot has also changed. Sales have doubled, and distribution has expanded beyond independent agents to the banks and independent broker-dealers. Big Wall Street firms like Apollo, KKR and Blackstone now have ownership shares in big FIA issuers. They have pioneered the investment of FIA premiums into private credit and other alternative assets.

The mainstreaming of the FIA might be the biggest change in the last 10 years. With Wall Street’s help, it has emerged from the shadows into the spotlight. The FIA survived attempts by the SEC and the Department of Labor to regulate it more closely. It was more adaptable to the post-Great Financial Crisis economic climate than other annuities. Its strength and weakness are its link to the equity markets; as equities go, so goes the FIA.

© 2022 RIJ Publishing LLC. All rights reserved.

“Although the ownership and management of the company may be different, the same people are working there, and doing the same jobs. Some private equity firms have just let the companies they acquire run as usual. Others, like Athene, Sammons, and Fidelity & Guaranty, have been aggressive in increasing sales. American Equity, which was normally near the top in sales, has been down a little,” Moore said. All four of those companies now leverage the expertise of firms with private equity and private credit expertise.

“Although the ownership and management of the company may be different, the same people are working there, and doing the same jobs. Some private equity firms have just let the companies they acquire run as usual. Others, like Athene, Sammons, and Fidelity & Guaranty, have been aggressive in increasing sales. American Equity, which was normally near the top in sales, has been down a little,” Moore said. All four of those companies now leverage the expertise of firms with private equity and private credit expertise.